File

advertisement

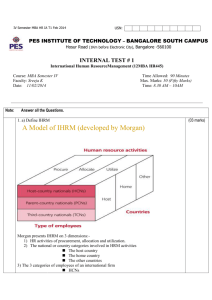

1 International Human Resource Development Running Head: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT International Human Resource Development Salma Hadeed Florida International University Dr. Thomas Reio Jr., PhD ADE 5387 2 International Human Resource Development When we think of international human resource development (HRD, what exactly are we interpreting this to mean? We see the words ‘international’, ‘human’ and ‘development’ but do we really know what HRD itself entails? Firstly, let’s define, or attempt to define what HRD is. A study by Bob Hamlin and Jim Stewart was conducted in 2011 on trying to review and synthesize the HRD domain. Dating back to Harbison and Myers (1964), these authors defied HRD as “the process of increasing the knowledge, the skills, and the capacities of all the people in the society.” Nadler (1970) defined it as “a series of organized activities conducted within a specified time and designed to produce behavioral change.” In 1983, Chalofsky and Lincoln stated that the discipline of HRD is “the study of how individuals and groups in organization change through learning.” Nadler and Wiggs (1986) defined it as “a comprehensive learning system for the release of the organization’s human potentials – a system that includes both vicarious (classroom, mediated, simulated) learning experiences and experimental, on-the-job experiences that are keyed to the organization’s reasons for survival.” In 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1999, 2001, 2004 and in 2005 definitions have been stated by many authors on what HRD is. But in 2006, Werner and DeSimone defined HRD as “a set of systematic and planned activities designed by an organization to provide its members with the opportunities to learn necessary skills to meet current and future job demands.” When we look at all of these definitions, we see a common theme: trying to improve through learning. International HRD is a little bit more complex in that it does not just pertain to HRD abroad. There are many different codes of conduct, laws and training methods involved. This research paper will take an in depth look at international HRD and what encompasses it in different countries such as France, Lebanon, Southern EU and also a cross-cultural training of European and American managers in Morocco. 3 International Human Resource Development HRD is practiced almost everywhere around the world in most firms and organizations. Some small firms might not have an HR department, but certain practices maintained by the employer or staff members incorporate HR practices. For instance, some employees might practice boosting morale, or using new team building techniques. It has been argued (Woodall et al., 2002a,b) that HRD in Europe is a much more “fuzzy” concept than it is understood to be in the USA. Furthermore, a recent comparison of HRD practices within Europe (Tjepkema et al., 2002) indicated that there were more similarities than differences between countries, and that diversity was mainly apparent in areas such as “rights to educational leave, differences in training taxes, fiscal deductibility of training costs, relationship between education and HRD, and differences in the transition from school-to-work practices” (Tjepkema et al., 2002, p. 17). Belet (2002) drawing on four case studies, noted some distinctive features of HRD in France, including a senior management commitment to continuous learning; a strong commitment to linking training strategy to corporate strategy; the delivery of a great deal of training away from the workplace in special corporate training centers; and a strong degree of HRD professionalism. Yet a recent study comparing HRD practices in seven European countries (Lafosse and Gerard, 2003) indicated that French companies give less priority management development, the development of high potential employees, career development, and training evaluation, and take a short-term rather than a long term perspective. Other research has noted that in France the HR function, as a rule, is seldom involved in the development of business strategy (Le Nagard and Rio, 2003). There are however reasons why such general assessments might cause such arguments; the first reason being how it relates to globalization on European economies while the second reason could be the company size being an important factor influencing the pattern of HRD 4 International Human Resource Development practices (Weil and Woodall, 2005). Thirdly, French discussion of HRD does not engage with the scholarly or professional debate on the rest of Europe, let alone the USA (Weil and Woodall, 2005). While much debate has included scholars from the UK, The Netherlands and other parts of Europe, both the scholarly and practitioner community in France have been silent about HRD (Weil and Woodall, 2005). Paradoxically the term “human resource development” is seldom referred to in France (Sambrook and Stewart, 2002) and the direct translation as developpement des ressources lumaines is not used in favor of terminology that has stronger connotations of social engineering (“formation professionelle”) social inclusion (development social) or social transformation (development du potential humain, Cadin et al., 2002). Because of this, the role of the HRD professionals is unclear. (Weil and Woodall, 2005) concluded their study by stating that HRD is not a clear concept held by leading HRD professionals in French firms and that on the whole, HRD appears subsumed within the wider HRD function. They continue to say that thre was also a mismatch between the language used in research into HRD and that used by French HRD professional practitioners, for example some concepts do not translate easily into English, for instance: “competencies management”, “staff mobility”, and “integration.” Today, it would be difficult to imagine any organization achieving and sustaining effectiveness without efficient human resource management programs and activities (Schuler, 2000). The workplace in Europe has faced some major changes during the last ten years (Dessler, 2000). According to Iversen (2000), important structural changes are being implemented during these years. Additionally, Ferner and Hyman (1992) claim that organizations in Europe face many changes in the business environment like increased international competition and slower growth. At the same time, changes within Europe in workforce demography, technology and other environmental aspects are creating the need for 5 International Human Resource Development new structures and management practices, which contribute to organizational commitment and flexibility (Iversen, 2000). Gven the importance of organizational effectiveness within an international context, it is imperative to investigate the challenges facing human resource management within the global economy (Stavrou-Costea, 2005). According to (Stavrou-Costea, 2005) five countries (Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus) with much in common were chosen to be examined. Some of the conclusions of the study by (Stavrou-Costea, 2005) include that some of the organizations should employ training, development flexibility and employee relations practices to achieve excellent organizational performance. They continue to say that “employers need to understand the importance of effective utilization of human resource management practices. This is especially significant for Cyprus, because of its recent accession in the European Union and thus, the organizational environment is becoming increasingly competitive.” The researchers stated that for Cyprus, government officials need to develop strategies that place more emphasis on the role of human resource management in organizations. (Stavrou-Costea, 2005) addressed the issue of effective training and development. As companies continue to embrace global market, a highly competitive environment for multinational organizations exists (Adler, 2002; Konopaske et al., 2005) resulting in the use of expatriates to manage global operations (Black and Gregersen, 1999). The success of multinational organizations is often dependent on these expatriates (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2001), expatriate development and training is critical to the companies’ growth and performance. Researching factors and practices that support expatriates’ adjustment to the international assignment is important, as prior research indicates that the expatriates’ job performance is strongly related to the expatriates’ adjustment to the international assignment (Parker and McEvoy, 1993; Kraimer et al.,, 2001). Feldman and Tompson (1992) indicate that expatriates 6 International Human Resource Development may face more obstacles to good performance on assignment than domestic employees face. Several studies conclude that expatriates’ difficulties adjusting and poor performance are costly, lead to low productivity, and may result in early termination of assignments (Tung, 1987; Black, 1988; Kaye and Taylor, 1997; Stori, 2001). While some expatriates succeed, some also fail. Expatriate failure results in costly consequence (Bennet et al., 2000). As Harzing (1995) reports, the failure rate of US expatriate managers has been exaggerated. However, when failure does occur, it is costly to organizations, including missed opportunities, poor productivity, ad diminished relationships that can be more costly than financial expenditures (Stori, 2001). Quite a number of studies have been conducted where the performance of an expatriate’s adjustment was measured with their performance. Cavusgil et al. (1992) suggests many expatriates may struggle adapting to the culture and thus operate at a decreased performance. Kraimer et al. (2001) confirmed this finding by stating “…finding a positive relationship between expatriate adjustment and performance, showing that well-adjusted expatriates who intact well with host nationals receive high performance ratings from supervisors on both task and contextual performance.” More recently, Takeuchi et al. (2005), in a longitudinal study, found expatriates work adjustment to be strongly correlated with performance. As the literature on expatriates continues to grow, the literature seems to indicate that expatriates adjustment is a critical aspect of the expatriates’ ability to meet their organizations’ goals and objectives (Caligiuri, 2000; Nicholson and Imaizumi, 1993; Kraimer et al., 2001). Expatriate employees who are not ready to embrace the culture of the host country might not be able to show the true potential that they by not performing. This was evident in a study conducted by researchers like [21] Harvey and Wiese (1998) and [27] Insch and Daniels (2002) who found that expatriates return from their overseas assignments prematurely due to problems 7 International Human Resource Development such as poor performance, culture shock, personal inconvenience and job dissatisfaction. Repatriation turnover has been a major source of concern for the multinational companies ([30] Lazarova and Cerdin, 2007). Therefore, much training needs to be done for all expatriates abroad. This is evident in a study conducted by Littrell et al. (2006) where he stated “traditional cross-cultural training focuses on preparing individuals for overseas assignments, multicultural training is directed at improving the cultural awareness of domestic employees in the hopes of improving their ability to interact with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds. Although expatriate assignments are viewed as a key human resource strategy for international corporations, in actuality, many expatriate managers are unsuccessful in the foreign organization (Baumgarten, 1995; Benney et al., 2000; Bhagat and Prien, 1996; Rahim, 1983). Even if the expatriate remains in the host country for the duration of the overseas assignment, his or her foreign assignment may be classified as unsuccessful for the following reasons: delayed productivity and start-up time, disruption of the relationship between the expatriate and host nationals, damage to the multi-national corporations image, lost opportunities, and problematic repatriation resulting in high turnover rates (Bennet et al., 2000). The expatriate manager may be unable to adapt to the physical and cultural differences of the environment; family members accompanying the expatriate may have adjustment difficulties; the expatriate may not possess the required personality skills for cross-cultural interaction the expatriate may lack technical abilities; or the expatriate may not be motivated to work overseas (Baumgarten, 1995; Bhagat and Prien, 1996; Tung, 1981). It is imperative to adequately train expatriates to perform well in overseas assignments; not only does this draw benefits to the company, it also helps the morale of the employees (Mansour and Wood, 2009). Mansour and Wood (2009) continue to say that one of the 8 International Human Resource Development difficulties in expatriate cross-cultural training research is the lack of foundation theories. The contingency theory of human resource training states that the fit between training and learning is critical to achieve better training effectiveness, meaning satisfaction, commitment and involvement of participants in work places (Kolb et al., 1995). A contingency-fit between the teaching modes of the instructor, the learning style of the student and the perceived cultural differences between parent country and host country may significantly influence the effectiveness of expatriate training (Vance and Paik, 2002). Blume et al. (2010) presented a meta-analysis on training transfer and explored the impact of predictive factors, such as trainee characteristics, work environment, and training interventions on transfer of training to different tasks and contexts. They found significant positive relationships between transfer and predictors such as cognitive ability, conscientiousness, motivation, and support of work environment. The ability to learn and to convert learning into practice creates extraordinary value for individuals, teams and organizations (Ashton and Green, 1996). International human resource development (HRD) researchers have recognized that organizational support and training are necessary for expatriates to do a good job in overseas assignments ([25] Hurn, 2007; [37] Osman-Gani and Tan, 2005; [39] Selmar, 2005; [35] OsmanGani, 2000; [9] Brewster, 1993; [20] Harvey, 1989). However, we need to also look at instances where the HRD practitioner returns to their country of origin: repatriation. Repatriation is considered the last stage of the expatriation process and is a very crucial part of the process. Because of the time spent and experience gained in the host country, the repatriate has an "altered perspective" and he/she is considered to be a changed person ([3] Andreason and Kinneer, 2005). Thus, he/she is likely to face readjustment problems after returning to the home country, given the changes in living and working conditions in the home country ([40] Shaffer et 9 International Human Resource Development al., 1999). A major problem in repatriation is the home organization's belief that returning home will not be difficult, but many repatriation researchers have found repatriation to be both challenging and complicated ([12] Cox, 2004). Repatriation problems associated with expatriates coming back from international assignments seldom receives the required organizational attention ([32] Linehan and Scullion, 2002). Issues like family/spouse adjustment, job-related problems and expectations - reality gap problems are often not discussed at the planning stage. [2] Allen and Alvarez (1998) argue that if these problems are not handled properly by the company, the total benefits of sending personnel on overseas assignments may not be realized. Some of the repatriates who return home without the proper training view their career path as a disaster because of the lack of planning which leads to anger, frustration and disappointment. Ultimately the company would have lost money in training their employees in the early stages of their career and would now have to spend more money to hire and train new employees. Organizations can therefore prepare the returning expatriate for changes that can impact their expectations and subsequent work adjustment ([33] MacDonald and Arthur, 2005). In an empirical study of Taiwanese repatriates, [31] Lee and Liu (2007) found support that a higher level of perceived repatriation adjustment and organizational commitment would encourage repatriates to stay. Both training and organization support are necessary to overcome obstacles associated with the process of repatriation ([26] Hyder and Lövblad, 2007). According to [28] Jassawalla et al. (2004), employees perceive training as an organizational support, increasing their motivation and their general satisfaction with the repatriation process. [43] Stroh et al. (1998) suggest that "repatriation training" will not only help to retain the employees in the company but will also make their life easier in the home environment that they left for the overseas assignment. [49] Vidal et al. (2007b) see training as a way to reduce uncertainty and 10 International Human Resource Development also to increase the psychological comfort of the repatriates in adjusting to the home environment. A study of MNEs in Singapore however showed that only 41 percent of locally-owned firms offered training abroad, and only 30 percent offered some repatriation training ([34] Osman-Gani et al. , 1995). Foreign-owned firms were slightly better: 55 percent provided training overseas, and 34 percent upon repatriation. Upon return, repatriates expect to be able to move back into the community, renew friendships, re-establish both business and social contacts, and fit easily back into their former lifestyles. [25] Hurn (2007) has observed that some companies provide a short repatriation program for their staff and this training can be done inhouse or by a specialist training institute. MacDonald and Arthur (2005) suggest that repatriation programs need to encourage and train employees to practice proactive career planning behaviors. The small amount of repatriation adjustment research that has been undertaken is dominated mainly by research on US expatriates and it may thus be questioned whether the findings of these studies hold true for other areas ([44] Suutari and Välimaa, 2002). Some researchers have looked on European multinationals' repatriation problems ([17] Gregersen, 1992), but such study is rare in Asia, which is increasingly becoming the focal point of global development, and home for many emerging multinationals. The recent work by [31] Lee and Liu (2007) is an exception as it addresses the issues of repatriation adjustment, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in predicting Taiwanese repatriates' intent to leave the organization during repatriation process. In conclusion, international human resource development plays a crucial part in any organization. The most important factor in this is the view and perspectives that the practitioners 11 International Human Resource Development have before going abroad, taking into consideration peoples’ culture and economic backgrounds. Proper training and development during all stages of expatriation must be considered if top performance and high productivity and efficient levels are expected. As Hinkin and Tracey (1999) pointed out, for organizations to improve and succeed in their industries they have to apply innovative management, especially for their human resources, to result in both organizational and individual improvements. 12 International Human Resource Development References Adler, N.J. (2002). International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, 4th ed., SouthWestern Thomson Learning, Cincinnati, OH. Andreason, A.W. and Kinneer, K.D. (2005). "Repatriation adjustment problems and the successful reintegration of expatriates and their families.” Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 6, 109-26. Ashton, D & Green, F. (1996). Education, Training and the Global Economy, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. Bennett, R., Aston, A. & Colquhoun, T. (2000). “Cross-cultural training: a critical step in ensuring the success of international assignments.” Human Resource Management, 39, 239-50. Black, J.S. (1988). “Work role transitions: a study of American expatriate managers in Japan.” Journal of International Business Studies, 19, 277-94. Black, J. & Gregersen, H. (1991). “Antecedents to cross-cultural adjustment for expatriates in Pacific Rim assignments.” Human Relations, 44, 497-515. Blume,B. Ford, J., Baldwin, T & Huang, J. (2010). “Transfer of training: a meta-analysis review.” Journal of Management, 36, 1065-105. Brewster, C. (1993). "The paradox of expatriate adjustment: UK and Swedish expatriates in Sweden and the UK.” Human Resource Management Journal, 41, 49-62. Caligiuri, P. Phillips, J., Lazarova, M., Tarique, I. & Biirgi, P. (2001). “The theory of met expectations applied to expatriate adjustment: the role of cross-cultural training.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12, 357-72. Cavusgil, T., Yavas, U. & Bykowicz, S. (1992). “Preparing executives for overseas Assignments.” Management Decision, 30, 54-8. 13 International Human Resource Development Chalosky, N. & Lincoln, C. (1983). Up the HR Ladder, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. Cox, B.J. (2004). "The role of communication, technology, and cultural identity in repatriation adjustment.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28, 201-19. Dessler, G. (2000). Human Resource Management, 8th ed., Prentice-Hall, Englewoods Cliffs, NJ. Dirani, K.M. (2012). “Professional training as a strategy for staff development: A study in training transfer in the Lebanese context.” European Journal of Training and Development, 36, 158-178. El Mansour, B. & Wood, E. (2010). “Cross-cultural training of European and American managers in Morocco.” Journal of European Industrial Training, 34, 381-392. Feldman, D.C. & Tompson, H.B. (1992). “Entry shock, culture shock: socializing the new breed of global managers.” Human Resource Management (1986-1998), 31, 345-62. Ferner, A. and Hyman, R. (1992). Industrial Relations in the New Europe, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Gupta, A. & Govindarajan, V. (2001). “Converting global presence into global competitive Advantage.” Academy of Management Executive, 15, 45-55. Hamlin, B. & Stewart, J. (2011). “What is HRD? A definitional review and synthesis of the HRD Domain.” Journal of European Industrial Training, 35, 199-220. Harbison, F.H. & Myers, C.A. (1964). Education, Manpower and Economic Growth: Strategies Of Human Resource Development, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Harvey, M. and Wiese, D. (1998). "Global dual-career couple mentoring: a phase model approach.” Human Resource Planning, 21, 33-48. 14 International Human Resource Development Harzing, A.W. (1995). “The persistent myth of high expatriate failure rates.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 6, 457-74. Hinkin, T. & Tracey, B. (1999). “The relevance of charisma for transformational leadership in stable organizations.” Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12, 105-19. Hurn, B.J. (1999). "Repatriation - the toughest assignment of all.” Industrial and Commercial Training, 31, 224-8. Hyder, A.S. and Lövblad, M. (2007). "The repatriation process - a realistic approach.” Career Development International, 12, 264-81. Insch, G. and Daniels, J. (2002). "Causes and consequences of declining early departures from foreign assignments.” Business Horizons, November/December, 39-48. Iversen, O.I. (2000). “Managing people towards a multicultural workforce. An investigation into the importance of managerial competencies across national borders in Europedifferences and similarities.” Paper presented at the 8th World Congress on Human Resource Management, Paris, 29-31 May. Jassawalla, A., Connolly, T. and Slojkowski, L. (2004). "Issues of effective repatriation: a model and management implications.” SAM Advanced Management Journal, 69, 38-46. Kaye, M. & Taylor, W. (1997). “Expatriate culture shock in China: a study in the Beijing hotel Industry.” Journal of Managerial Psychology, 12, 496-503. Kolb, D. Osland, J. & Rubin, I. (1995). Organizational Behavior: An Experimental Approach, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Konopaske, R., Robie, C. & Ivancevich, J.M. (2005). “A preliminary model of spouse influence on managerial global assignment willingness.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 405-26. Lazarova, M. and Caligiuri, P. (2001). "Retaining repatriates: the role of organizational support practices.” Journal of World Business, 36, 389-401. 15 International Human Resource Development Lee, H-W. and Liu, C-H. (2007). "An examination of factors affecting repatriates' turnover intentions.” International Journal of Manpower, 28, 122-34. MacDonald, S. and Arthur, N. (2005). "Connecting career management to repatriation adjustment.” Career Development International, 10, 145-58. Nadler, L. (1970), Developing Human Resources, Gulf, Houston, TX. Nadler, L. & Wiggs, C. (1986). Managing Human Resource Development: A Practical Guide, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA. Nicholson, N. & Imaizumi, A. (1993). “The adjustment of Japanese expatriates to living and working in Britain.” British Journal of Management, 4, 355-79. Parker, B. & McEnvoy, G. (1993). “Initial examination of a model of intercultural adjustment.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17, 355-79. Schuler, S.R. & Jackson, E.S. (2000). Managing Human Resources: A Partnership Perspective, South-Western College Publishing, Cincinnati, OH. Selmar, J. (2005). "Cross-cultural training and expatriate adjustment in China: western joint venture managers.” Personnel Review, 34, 68-84. Stavou-Costea, E. (2005). “The challenges of human resource management towards organizational effectiveness: A comparative study in Southern EU.” Journal of European Industrial Training, 29, 112-134. Storti, C. (2001), The Art of Crossing Borders, Nicholas Brealey and Intercultural Press, London. Stroh, L.K. (1995). "Predicting turnover among repatriates: can organizations affect retention rates?.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 6,443-56. Tung, R.L. (1987). “Expatriate assignments: enhancing success and minimizing failure.” Academy of Management Executives, 1, 117-25. 16 International Human Resource Development Vance, C. and Paik, Y. (2002). “One size fits all in expatriate pre-departure training? Comparing the host country voices of Mexican, Indonesian and US workers.” The Journal of Management Development, 21, 117-25. Vidal, M.E.S., Valle, R.S., Aragón, M.I.B. and Brewster, C. (2007b). "Repatriation adjustment process of business employees: evidence from Spanish workers.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31,317-37. Werne, J.M. & DeSione, R.L. (2006). Human Resource Development, 4th ed., Thomson SouthWestern, Mason, OH.