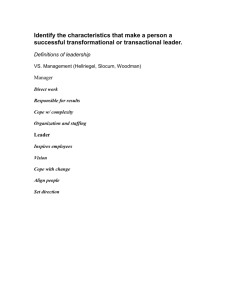

Charismatic & Transformational Leadership

advertisement