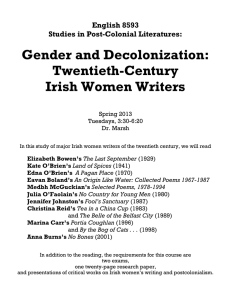

The Irish in 19th Century Chester and Poor Law Inequalities.

advertisement

The Irish in 19th Century Chester and Poor Law Inequalities. Dr Lorie Charlesworth LJMU Contents • 1/. Introduction Poor Law and the Irish • 2/. The Poor Law in Ireland: a comparative legal analysis • 3/. The Famine; initial stages and then the British Government’s response • 4/. The Great Hunger as genocide • 5/. Conclusions A Legal Right to Relief The law of settlement and removals comprises that part of English poor law that states poor people who possess a settlement in a parish (the settled poor) have the right, when destitute, to the poor relief provided by that parish. The post-reformation origins of the poor law are generally stated to be in An Act for the Better Relief of the Poor 1601 which formalised and codified under statute a system of poor relief based upon the parish where a duty to relieve the poor combined with a funding system raised by a local rate. The terms and purposes of that Act remained the legal authority for the relief of poverty in England and Wales until 1948. Poor Law as Law Possession of a settlement was not simply a collection of rules concerning residence qualifications. In plain language it consists of the fundamental state of belonging to a particular place. Belonging so thoroughly that all the other residents of that place owed a financial duty to Any settled person who had fallen into poverty. That duty, could involve payment of rent, food, goods, and money for that individual and his family; this the parish decided. However, that duty, exercised by parishioners via the poor rate, could not be shirked or avoided. Failure to pay the poor rate could lead to the seizure of goods or imprisonment. This belonging, if the legal proofs were present, constituted possessing a settlement. Most importantly, settlement law granted the settled poor the legal right to relief at common law, as a legal obligation enforceable by them in person against the poor law officers of the settlement parish. Thus the parish had a legal duty to relieve the pauper when destitute, enforceable by the pauper himself upon application to the justices, this could take place wherever the justice happened to be, including in the justice's home. Any Order to relieve issued by the justice had to be obeyed by parish officials, on pain of fines. Nolan, Treatise, vol. II, pp. 169-170 and 227-232. No Starvation However, more importantly, each settled person was legally entitled at common law to poor relief from his parish when destitute. Eventually that right to relief in emergency was extended to non-settled paupers in any parish, but such paupers remained vulnerable to removal by that parish. After 1803 that right was confirmed as extending to destitute foreigners when Lord when Lord Ellenborough stated: “As to there being no obligation for maintaining poor foreigners before the statutes ascertaining the different methods of acquiring settlements, the law of humanity, which is anterior to all positive laws, obliges us to afford them relief, to save them from starving” R v Eastbourne (Inhabitants) (1803) 4 East 103 at 107. 102 E.R., 769 at 770. If a poor person died of want due to failure to relieve then the Overseer or later Relieving Officer could be indicted for manslaughter. Irish and the Poor Law The Irish, the Scots and foreigners were ‘outside’ the poor law system as they possessed no settlement in England and Wales; although as casual migrants they could be designated as vagrants. However, the terms of a 1662 Act differentiated the Irish and the Scots from the Welsh and English poor whilst powers contained in the various vagrancy statutes were often used to return them home. Irish Poor in England pre 1819 Local administrative approaches were twofold, either the Irish were bought off with casual payments, or they were punished as ‘vagrants’ and returned home. The Irish generally acquired no settlement within England and the pressures that induced their patterns of migration remain largely unchanged. They were stigmatised by the general view of vagrants as respectability was understood to include some intention to remain, Irish migrants rarely had that intention. This was still true of the mid eighteenth century. By 1796, the united parishes of St. Giles and St. George. Bloomesbury paid £200 relief for casual poor, comprising: ‘1,200 poor natives of Ireland’. Irish in Chester 1847 On 14 February 1847 the Chronicle reports over 300 destitute Irish are relieved with soup, coal and money from Father Carberry and his Charity. The newspaper notes these: ‘unfortunate and starving creatures were huddled up in large numbers in very confined and filthy dwellings.’ Poor Law Act Ireland 1838 Unlike English poor law, whose legal authority depended upon the originating terms of the 1601 Act subsequent statutes and a developed case law, the Irish Act was imposed without the comparable legal, administrative and protective elements that had existed in England for centuries. Most notable:• No legal right to relief from destitution for a settled pauper • No administrative autonomy of civil parishes or townships, which set and collected a poor rate that was demand-led and uncapped . Famine • Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, by Amartya Sen, published in 1981. Legality and Famine Sen posits that relevant factors such as market conditions can be seen operating through a system of legal relations. He concludes: ‘the law stands between food availability and food entitlement. Starvation deaths can reflect legality with a vengeance’. Sen, Poverty, 166. • Genocide Convention 1948 Genocide is defined as: … any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: Article II defines genocide as: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. Guilty? • Article III: The following acts shall be punishable: • (a) Genocide; (b) Conspiracy to commit genocide; (c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide; (d) Attempt to commit genocide; (e) Complicity in genocide.