Organization Development Lecture 5

advertisement

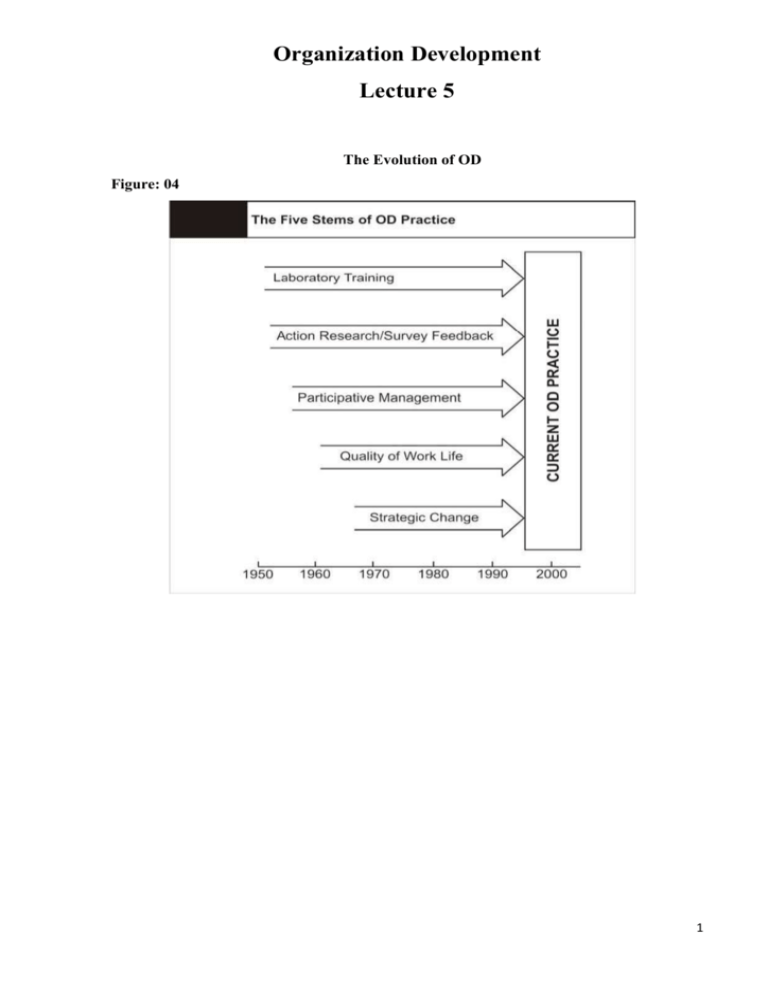

Organization Development Lecture 5 The Evolution of OD Figure: 04 1 3. Participative Management The intellectual and practical advances from the laboratory training stem and the action research/survey-feedback stem were followed closely by the belief that a human relations approach represented a one-best-way to manage organizations. This belief was exemplified in research that associated Likert’s Participative Management (System 4) style with organizational effectiveness. This framework characterized organizations as having one of four types of management systems: Exploitative authoritative systems (System 1) exhibit an autocratic, top-down approach to leadership. Employee motivation is based on punishment and occasional rewards. Communication is primarily downward, and there is little lateral interaction or teamwork. Decision making and control reside primarily at the top of the organization. System 1 results in mediocre performance. Benevolent authoritative systems (System 2) are similar to System 1, except that management is more paternalistic. Employees are allowed a little more interaction, communication, and decision making but within boundaries defined by management. Consultative systems (System 3) increase employee interaction, communication, and decision making. Although employees are consulted about problems and decisions, management still makes the final decisions. Productivity is good, and employees are moderately satisfied with the organization. Participative group systems (System 4) are almost the opposite of System 1. Designed around group methods of decision making and supervision, this system fosters high degrees of member involvement and participation. Work groups are highly involved in setting goals, making decisions, improving methods, and appraising results. Communication occurs both laterally and vertically, and decisions are linked throughout the organization by overlapping group membership. System 4 achieves high levels of productivity, quality, and member satisfaction. Likert applied System 4 management to organizations using a survey-feedback process. The intervention generally started with organization members completing the Profile of Organizational Characteristics. The survey asked members for their opinions about both the present and ideal conditions of six organizational features: leadership, motivation, communication, decisions, goals, and control. In the second stage, the data were fed back to different work groups within the organization. Group members examined the discrepancy between their present situation and their ideal, generally using System 4 as the ideal benchmark, and generated action plans to move the organization toward System 4 conditions 2 Quality of Work Life: The contribution of the productivity and quality-of-work (QWL) background to OD can be described in two phases. The first phase, starting in 1950s, aimed at better integrating technology and people. These QWL programs generally involved joint participation by unions and management in the design of work and resulted in work designs giving employees high levels of discretion, task variety, and feedback about results. Perhaps the most distinguishing characteristic of these QWL programs was the development of self-managing work groups as a new form of work design. These groups were composed of multiskilled workers who were given the necessary autonomy and information to design and manage their own task performances. Two definitions of QWL emerged during its initial development. QWL was first defined in terms of people’s reaction to work, particularly individual outcomes related to job satisfaction and mental health. Using this definition, QWL focused primarily on the personal consequences of the work experience and how to improve work to satisfy personal needs. A second definition of QWL defined it as an approach or method. People defined QWL in terms of specific techniques and approaches used for improving work. It was viewed as synonymous with methods such as job enrichment, self-managed teams, and labormanagement committees. This technique orientation derived mainly from the growing publicity surrounding QWL projects, such as ….. Starting in 1979, a second phase of QWL activity emerged. A major factor contributing to the resurgence of QWL was growing international competition faced by the US in markets at home and abroad. It became increasingly clear that the relatively low cost and high quality of foreign-made goods resulted partially from the management practices used abroad, especially in Japan. As a result, QWL programs expanded beyond their initial focus on work design to include other features of the workplace that can affect employee productivity and satisfaction, such as reward systems, work flows, management styles, and the physical work environment. This expanded focus resulted in larger-scale and longer-term projects than had the early job enrichment programs and shifted attention beyond the individual worker to work groups and the larger work context. Equally important, it added the critical dimension of organizational efficiency to what had been up to that time a primary concern for the human dimension. At one point, the productivity and QWL approach became so popular that it was called an ideological movement. This was particularly evident in the spread of quality circles within 3 many companies. Popularized in Japan, quality circles are groups of employees trained in problem-solving methods who meet regularly to resolve work-environment, productivity, and quality-control concerns and to develop more efficient ways of working. Today, this second phase of QWL activity continues primarily under the banner of “employee involvement,” rather than of QWL. For many OD practitioners, the term “EL” signifies, more than the name QWL, the growing emphasis on how employees can contribute more to running the organization so it can be more flexible, productive, and competitive. Recently, the term “employee empowerment” has been used interchangeably with the term EL, the former suggesting the power inherent in moving decision making downward in the organization. Employee empowerment may be too restrictive, however. Because it draws attention to the power aspects of these interventions, it may lead practitioners to neglect other important elements needed for success, such as information, skills, and rewards. Consequently, EL seems a broader and less restrictive banner than does employee empowerment for these approaches to organizational improvement. Finally, the productivity and QWL approach has gained new momentum by joining forces with the total quality movement advocated by Demming & Juran. In this approach, the organization is viewed as a set of processes that can be linked to the quality of products and services, modeled through statistical techniques and improved continuously. Strategic Change: The strategic change stem is a recent influence on OD’s evolution. As organizations and their technological, political, and social environments have become more complex and more uncertain, the scale and intricacies of organizational change have increased. This trend has produced the need for a strategic perspective from OD and encouraged planned change process at the organization level. Strategic change involves improving the alignment among an organization’s environment, strategy, and organization design. Strategic change interventions include efforts to improve both the organization’s relationship to its environment and the fit between its technical, political, and cultural systems. The need for strategic change is usually triggered by some major disruption to the organization, such as the lifting of regulatory requirements, a technological breakthrough, or a new chief executive officer coming in from outside the organization. 4 One of the first applications of strategic change was Richard Beckhard’s use of open system planning. He proposed that an organization’s environment and its strategy could be described and analyzed. Based on the organization’s core mission, the differences between what the environment demanded and how the organization responded could be reduced and performance improved. Since then, change agents have proposed a variety of large-scale or strategic change models, each of which recognizes that strategic change involves multiple levels of the organization and a change in its culture, is often driven from the top by powerful executives, and has important effects on performance. The strategic change stem has significantly influenced OD practice. For example, implementing strategic change requires OD practitioners to be familiar with competitive strategy, finance, and marketing, as well as team building, action research, and survey feedback. Together, these skills have improved OD’s relevance to organizations and their managers. A Model for Organizational Development: Organization development is a continuing process of long-term organizational improvement consisting of a series of stages; the emphasis is placed on a combination of individual, team, and organizational relationships. The primary difference between OD and other behavioral science techniques is the emphasis upon viewing the organization as a total system of interacting and interrelated elements. Organization development is the application of an organization-wide approach to the functional, structural, technical, and personal relationships in organizations. OD programs are based upon a systematic analysis of problems and a top management actively committed to the change effort. The purpose of such a program is to increase organizational effectiveness by the application of OD values and techniques. Many organization development programs use the action research model. Action research involves collecting information about the organization, feeding this information back to the client system, and developing and implementing action programs to improve system performance. The manager also needs to be aware of the processes that should be considered when one is attempting to create change. This section presents a five-stage model of the total organization development process. Each stage is dependent on the preceding one, and successful change is more probable when each of these stages is considered in a logical sequence. 5 Figure: 05 Organization Development’s Five Stages Stage One: Anticipate a Need for Change: Before a program of change can be implemented, the organization must anticipate the need for change. The first step is the manager's perception that the organization is somehow in a state of disequilibrium or needs improvement. The state of disequilibrium may result from growth or decline or from competitive, technological, legal, or social changes in the external environment. There must be a felt need, because only felt needs convince individuals to adopt new ways. Managers must be sensitive to changes in the competitive environment, to "what's going on out there." When a new CEO of AT&T Corporation took over, he made it clear to top executives that it was not business as usual. In his first week as CEO, he brought in the company's top 20 officers to tell them that the company's tradition of keeping people in top jobs as long as they didn't mess up was over. According to one person at the meeting, the CEO said "You are going to be in my boat or out of it. But don't be there barking or rowing against it. Stage Two: Develop the Practitioner-Client Relationship: After an organization recognizes a need for change and an OD practitioner enters the system, a relationship begins to develop between the practitioner and the client system. The client is the person or organization that is being assisted. The development of this relationship is an important determinant of the probable success or failure of an OD program. As with many 6 interpersonal relationships, the exchange of expectations and obligations (the formation of a psychological contract) depends to a great degree upon a good first impression or match between the practitioner and the client system. The practitioner attempts to establish a pattern of open communication, a relationship of trust and an atmosphere of shared responsibility. Issues dealing with responsibility, rewards, and objectives must be clarified, defined, or worked through at this point. The practitioner must decide when to enter the system and what his or her role should be. For instance, the practitioner may intervene with the sanction and approval of top management and either with or without the sanction and support of members in the lower levels of the organization. At one company, OD started at the vice-presidential level, and by using internal OD practitioners the OD program was gradually expanded to include line managers and workers. At another company, an external practitioner from a university was invited in by the organization's industrial relations group to initiate the OD program. Stage Three: The Diagnostic Phase: After the OD practitioner has intervened and developed a working relationship with the client, the practitioner and the client begin to gather data about the system. The collection of data is an important activity providing the organization and the practitioner with a better understanding of client system problems: the diagnosis. One rule of operation for the OD practitioner is to question the client's diagnosis of the problem, because the client's perspective may be biased. After acquiring information relevant to the situation perceived to be the problem, the OD practitioner and client together analyze the data to identify problem areas and causal relationships. A weak, inaccurate, or faulty diagnosis can lead to a costly and ineffective change program. The diagnostic phase, then, is used to determine the exact problem that needs solution, to identify the forces causing the situation, and to provide a basis for selecting effective change strategies and techniques. Although organizations usually generate a large amount of "hard" or operational data, the data may present an incomplete picture of organizational performance. The practitioner and client may agree to increase the range or depth of the available data by interview or questionnaire as a basis for further action programs. One organization, for instance, was having a problem with high employee turnover. The practitioner investigated the high turnover rate by means of a questionnaire to determine why the problem existed, and from these data designed an OD program to correct the problems. The firm's employees felt it had become a bureaucratic organization clogged with red tape, causing high turnover. 7 OD programs have since reduced employee turnover to 19 percent, compared with 34 percent for the industry. At a major food company, a new executive vice president needed to move quickly to improve the division's performance. With the help of an external practitioner, data were gathered by conducting intensive interviews with top management, as well as with outsiders, to determine key problem areas. Then, without identifying the source of comments, the management team worked on the information in a 10-hour session until solutions to the major problems was hammered out and action plans developed. Stage Four: Action Plans, Strategies, and Techniques: The diagnostic phase leads to a series of interventions, activities, or programs aimed at resolving problems and increasing organization effectiveness. These programs apply such OD techniques as total quality management (TQM), job design, role analysis, goal setting, team building, and inter-group development to the causes specified in the diagnostic phase (all of these techniques are discussed in detail in subsequent chapters). In all likelihood, more time will be spent on this fourth stage than on any of the other stages of an OD program. Stage Five: Self-Renewal, Monitor, and Stabilize: Once an action program is implemented, the final step is to monitor the results and stabilize the desired changes. This stage assesses the effectiveness of change strategies in attaining stated objectives. Each stage of an OD program needs to be monitored to gain feedback on member reaction to the change efforts. The system members need to know the results of change efforts in order to determine whether they ought to modify, continue, or discontinue the activities. Once a problem has been corrected and a change program is implemented and monitored, means must be devised to make sure that the new behavior is stabilized and internalized. If this is not done, the system will regress to previous ineffective modes or states. The client system needs to develop the capability to maintain innovation without outside support. 8 Continuous Improvement: In today's environment, companies seeking to be successful and survive are faced with the need to continually introduce changes. The unlikely has become commonplace, and the unthinkable has become almost inevitable. The most important Lecture managers need to learn is that there are only two kinds of companies — those that are changing, and those that are going out of business. Continual change is a way of life. A critical challenge for managers who are leading change efforts is to inspire individuals to work as a team. This five stage model shows how different OD methods and approaches are used to continuously improve performance so that the vision can be achieved. It is important to remember that no model or paradigm is perfect, but it can still provide useful approaches to change. As an OD program stabilizes, the need for the practitioner should decrease. If the client moves toward independence and evidences a self-renewal capacity, the gradual termination of the practitioner-client system relationship is easily accomplished. If the client system has become overly dependent upon the practitioner, termination of the relationship can be a difficult and awkward issue. At one company, for example, the program produced tangible benefits. Of 264 managers involved in the program, 93 percent reported that the program led to improved teamwork. One important issue in the implementation of an OD program is whether or not the practitioner is able to deal effectively with power and the use of power. Hierarchical organizations, whether they be business, governmental, for-profit, or not-for-profit, rely on power. The individuals in positions of influence generally constitute the power structure and frequently are powermotivated people. Managers compete for promotions, and departments and divisions have disagreements over budget allocations, Political infighting is a reality (and often a dysfunctional factor) in most organizations, and the issue is whether OD practitioners deal with these power issues in bringing about a change. In a study of high-speed decision making, Kathleen Eisenhardt and L. J. Bourgeois III found that politics influence decisions and those political conflicts "within top management teams are associated with poor firm performance. The OD practitioner acts as a facilitator to promote team problem solving and collaboration, and encourages such values as trust, openness, and consensus. Given the nature of an OD program, it is our view that OD is not a political/power type of intervention. Given the political nature of organizational decision making, however, the OD practitioner must be aware of politics and use a problem-solving approach that is compatible with power-oriented situations. 9