Burton 1

Thomas Burton 7104

Dr. Whit Jones

Expository Writing

4-30-12

Sex Education: Should it be the School’s Responsibility?

The question of whether sex education should be the school’s responsibility has

sparked some debate among schools and the parents of the students who attend them.

Because sex is such a sensitive subject, most people tend to have relatively strong

opinions on how their children should learn about it—how detailed the explanation

should be and at how early of an age sex education should begin. Though it is such a

delicate topic and is involved in so many issues—morality, identity, biology—most

parents would insist that the school systems, and therefore the government, take on the

responsibility of explaining sex to their children. Wouldn’t they rather bring it up

themselves, and be able to impart whatever wisdom and beliefs they have concerning

it?

Researcher Sharon Alexander took a poll on this subject, surveying the parents

of students attending various public schools on the East Coast, as well as Rocky

Mountain areas. She reported her findings in her article “Improving Sex Education

Programs for Young Adolescents: Parents’ Views.” Alexander found that more than

eighty percent of parents were in favor of sex education in the public schools. Over sixty

percent felt that the programs should be expanded (251, 253). Because of these results,

Alexander argues that they should, indeed, be expanded. Authors Lawrence and Ellen

Shornack, in their article “The New Sex Education and the Sexual Revolution: A Critical

Burton 2

View”, disagreed, arguing that sex education in public schools undermined the place of

the family.

Why are so many parents insisting that the schools take over when it comes to

sex education? Authors and psychologists, Drs. Shornack, believe that because of the

mixed authorities in the lives of many adolescents today, parents in general no longer

feel that they can make decisions for their children. Because sex is such a sensitive

topic, and conversations about it can be awkward for parents and their kids, most

parents tend to just avoid the subject (532). The majority of parents cover very few

sexual topics with their children, even when it comes to personal issues like

masturbation, homosexuality, abortion, and contraception methods. Indeed, most

parents only talked with their children about the basic differences between girls and

boys (Alexander 254).

Alexander proposes that many parents are afraid that they won’t be able to cover

the topics well enough. Most parents aren’t experts on STD’s or the menstrual cycle. So

they believe that the school, so full of educated people, will be able to do a better job

than they would. Unfortunately, most schools don’t have a developed sex education

program. Even the ones that do often don’t have an encompassing curriculum. Many

times, teachers resort to magazines and health textbooks to cover the more technical

aspects of reproduction (252). That, of course, is something the parents themselves

could do.

Because parents and schools typically fail to properly inform the students, the

children turn to their peers and the media, even though most parents would still

consider themselves to be their child’s primary source for sexual information, as

Burton 3

Alexander points out (253). The students’ peers usually don’t know any more about sex

than they themselves do. The media casts sex as mere recreation, a view that neither

parents nor schools would tend to agree with. Along with that comes the belief that

women are sex objects to be victimized and used, crushing girls’ self-esteem (Shornack

and Shornack 536). Both of these lead to a distorted view of sexuality.

Having an inaccurate view of sexuality can become negative because sex isn’t

just about the “plumbing”, but is accompanied by emotional and relational aspects as

well. Sex education is more than just sex information (Shornack and Shornack 531).

Most parents would agree that sex education should have some sort of morals and

values incorporated in it, though what morals those should be is always controversial.

The Shornacks take it a step further, saying that “Teaching anatomy and physiology is

imparting the mere plumbing of sexuality and may even be dehumanizing” (532). Sex

viewed as a simply biological issue lends to the view that it can be abused without

having any negative impacts on the people involved.

Having a distorted view of sexuality ends up negatively affecting nearly all

aspects of an adolescent’s social life, from how he relates with his parents to how he

behaves toward his friends. Women become cast in a role that sets them up as

belongings, rather than people. Men become viewed as always taking advantage of

every situation and weakness. The Shornacks believe that it is not the presence of pop

culture or negative peer influence that degrades morality, self-esteem, and sexuality.

Rather, it is the absence of family involvement in the child’s life. Mothers no longer help

their children to deal with stress and frustration, nor do fathers provide strength and

support (538).

Burton 4

In the past few decades, the norms of relational agreements have broken down.

Marriage has become a joke, and traditional dating is nonexistent. Many students grow

up in a home with divorced parents, domestic partners, or nearly raise themselves. This

often leads them to act out. When a youth acts out their conflicts, rather than working

through them, the immature narcissism and reliance on adults is only prolonged

(Shornack and Shornack 538).

This acting out very often comes in seeking the intimacy they never found at

home and can take on the form of sexual experimentation. This has a negative longterm effect on the students. College women who were more openly sexual in their high

school years reported experiencing less happiness and a lower popularity (Shornack

and Shornack 537).

The Shornacks would suggest that the answer to this is simple; the family needs

to reenter the scene as a major influence in the students’ lives. If there is a school-run

sex education program, it can’t merely teach the physical aspects of sexuality. Rather, it

should result in students becoming rational about sex and therefore becoming

responsible concerning it (533).

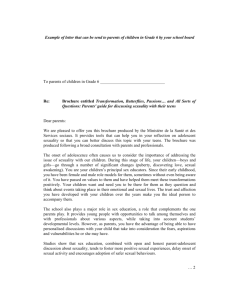

Alexander, on the other hand, would suggest that the problems aren’t based on

the family, and so neither are the solutions. She would propose that we have a flawed

system when it comes to sex education. The programs in general are inadequate for

teaching our children what they need to know. The curriculum is almost nonexistent, the

teachers are not well trained, and the students are not well reached (252-253).

Alexander says that the way our sex education programs are designed should be

expanded and improved. Teachers teaching from magazines should have some sort of

Burton 5

standardized curriculum, though that curriculum should be re-evaluated every so often.

She states that what and when students are taught should be carefully considered,

based on what the local parents believe and want taught, and the curriculum should be

restructured based on that. Alexander believes that if the students know everything

there is to know about sex, then responsibility will just fall in line.

In contrast, the Shornacks point out that “even if all sexually active teenagers

used contraception consistently, 467,000 premarital pregnancies would occur each year

anyway” (536). They quote researcher K. Davis in saying,

The current belief that illegitimacy will be reduced if teenage girls are

given an effective contraceptive is an extension of the same reasoning

that created the problem in the first place. It reflects an unwillingness to

face problems of social control and social discipline, while trusting some

technological device to extricate society from its difficulties. (535)

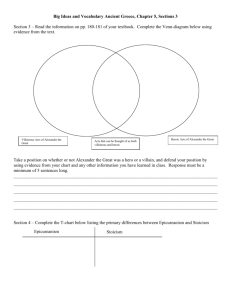

While both Alexander and the Shornacks seem to support family and school

intervention in the students’ sexual education, both come to radically different

conclusions as to some solution to these problems. The Shornacks insist that the family

must stabilize itself before it can become some kind of influence. Then the parents need

to get over their fears and become their child’s greatest influence, especially in sensitive

areas like sexuality. Alexander believes that if the public schools’ sex education

programs were restructured in accordance with the parents’ needs and wishes, and

some adequate curriculum was designed for the programs, then the school would be all

that is necessary, reflecting what the parents wish they could say.

Burton 6

I would agree with both arguments at different points. I agree with the Shornacks

that sex education should primarily be the family’s responsibility. I think that such a

personal topic should be covered by people who know you best. However, some

parents truly aren’t qualified or willing to teach their children. Public sex education

should be offered, but not by the public school system, which is government regulated. I

think that it should be organized by the community, everyone making sure that the

information is adequate. The sex education course that I attended in high school only

taught about STD’s, working as a scare tactic to keep everyone abstinent. The

government and medical community could have a suggested curriculum that could be

changed in accordance to the needs of the community it is being taught in. In that

regard, I agree with Alexander.

Alexander and the Shornacks both made valid points in their articles and backed

up their reasoning with plenty of data and statistics. However, with such differing

opinions, both solutions cannot be right. Some solution must be enacted to combat the

inadequacies of sex education and the distorted views of sexuality that result from it.

Burton 7

Citations

Alexander, Sharon. "Improving Sex Education Programs for Young Adolescents:

Parents' Views." Family Relations. 33.2 (1984): 251-57. JSTOR. 14 Feb. 2012.

Shornack, Lawrence, and Ellen Shornack. "The New Sex Education and the Sexual

Revolution: A Critical View." Family Relations. 31.4 (1982): 531-44. JSTOR. 14

Feb. 2012.