Is this ethical

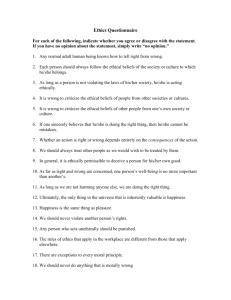

advertisement

CHAPTER 9 Ethics in Negotiation The Titles 1. A Sample of Ethical Quandaries 2. What Do We Mean by “Ethics” and Why do They Matter in Negotiation? 3. Four Approaches to Ethical Reasoning 4. What Questions of Ethical Conduct Arise in Negotiation? 5. Why Use Deceptive Tactics? Motives and Consequences. 6. What Factor Shape a Negotiator’s Predisposition to Use Unethical Tactics? 7. How Can Negotiator Deal with the Other Party’s Use of Deception? 8. Chapter Summary 1. A Sample of Ethical Quandaries • After reading the situations below, consider several questions here: • (1) Is it ethical to have said what you said about having another offer? • (2) Is this an ethical course of action? Would you be likely to do it if you were the entrepreneur? • (3) Do any of the strategies raise ethical concerns? Which ones? Why? • (4) Is this ethical ? Would you be likely to do this if you were this particular student? • (5) Is this ethical ? Would you be likely to do this if you were this customer? 2.What Do We Mean by “Ethics” and Why Do They Matter in Negotiation? -1 • Ethics Defined It is broadly social standards for what is right or wrong in a particular situation, or process for setting those standards. They differ from morals, which are individual and personal beliefs about what is right and wrong. Ethics grow out of particular philosophies, which purport to define the nature of the world I which we live, and prescribe rules for living together. Our goal is to distinguish among different criteria, or standards, for judging and evaluating a negotiator’s actions, particularly when questions of ethics may be involved. 2.What Do We Mean by “Ethics” and Why Do They Matter in Negotiation? -2 • Applying Ethical Reasoning to Negotiation The example shows that the approach to ethical reasoning you favor affects the kind of ethical judgment you make, and the consequent behavior you choose, in a situation that has an ethical dimension to it . • Ethics versus Prudence versus Practically versus Legality On the one hand, negotiators see some tactics as marginal—defined in shades and degrees rather than in absolutes. On the other hand, negotiators show marked agreement that certain tactics are clearly unethical. Although it maybe difficult to tell a negotiator Figure 9.1 Analytical Process for the Resolution of Moral Problems Understand all Moral standards Determine the Economic outcomes Define complete Moral problem Recognize all moral impacts: Benefits to some Harm to others Rights exercise Rights denied Consider the Legal requirements Evaluate the ethical duties Process Convincing Moral solution 3. Four Approaches to Ethical Reasoning -1 • Those who write about business ethics tend to approach the subject from the perspectives of major philosophical theories (see table 9.1). • Drawing on this literature, we will now take a closer look at the four ethical standards for making decisions in negotiation that we introduced above: End-Result Ethics, Duty Ethics, Social Contract Ethics, and Personalistic Ethics. 3.1 End-Result Ethics • Many of the ethically questionable incidents in business that upset the public involve people who argue that the ends justify the means—that is, who deem it acceptable to break a rule or violate a procedure in the service of some greater good for the individual, the organization, or even society at large. • In the negotiation context, when negotiators have noble objectives to attain for themselves or their constituencies, they will argue that they can use whatever strategies 3.2 Duty Ethics • Duty ethics emphasize that individual ought to commit themselves to a series of moral rules or standards and make decisions based on those principles. • When addressing means—ends questions in competition and negotiation, observers usually focus the most attention on the question of what strategies and tactics may be seen as appropriate to achieve certain ends. • Clearly, deontology has its critics as well. Who sets the standards and make the rules? What are rules that apply in all circumstances? 3.3 Social Contract Ethics • Social contract ethics argue that societies, organizations, and cultures determine what is ethically appropriate and acceptable for themselves and then indoctrinate new members as they are socialized into fabric of the community. • Social contract ethics focus on what individuals owe to their community and what they can or should expect in return. • As applied to negotiation, Social contract ethics would prescribe which behaviors are appropriate in a negotiation context in terms of what people owe one another. 3.4 Personalistic Ethics • As fourth standards of ethics is that, rather than attempting to determine what is ethical based on ends, duties, or the social norms of a community, people should simply consult their own conscience. • The very nature of human existence leads individuals to develop a personal conscience, an internal sense of what is right and what one ought to do. • Applied to negotiation, personalistic ethics maintain that everyone ought to decide for themselves what is right based on their 3.5 Summary • In this section, we have reviewed four major approaches to ethical reasoning. Negotiators may use each of these approaches to evaluate appropriate strategies and tactic. • We will next explore some of factors that tend to influence, if not dictate, how negotiators are disposed to deal with ethical questions. 4. What Questions of Ethical Conduct Arise in Negotiation • In this section, we will discuss negotiation tactics that bring issues of ethically in to play. • We will first discuss what we mean by tactics that are “Ethically Ambiguous”, and we will link negotiator ethics to the fundamental issue of truth telling. Then describe the research that has sought to identify and classify such tactics and analyze people’s attitudes toward their use. And then also distinguish between active 4.1 Ethically Ambiguous Tactics: It’s (Mostly) All About The Truth • Most of the ethics issues in negotiation are concerned with standards of truth telling—how honest, candid, and disclosing a negotiator should be. The attention here is more on what negotiators say or what they will do than on what they actually do. • Bluffing, exaggeration, and concealment or manipulation of information are legitimate ways for both individuals and corporations to maximize their self-interest. • As we pointed out when we discussed interdependence, negotiation is based on information dependence—the exchange of information regarding the true preferences and 4.2 Identify Ethically Ambiguous Tactics and Attitudes toward Their Use-1 • What Ethically Ambiguous Tactics Are There? See those six categories listed in Table 9.2, it is interesting to note that two of those are viewed as generally appropriate and likely to be used. And the other four, are generally seen as inappropriate an unethical in negotiation. • Does Tolerance for Ethically Ambiguous Tactics Lead to Their Actual Use? 4.2 Identify Ethically Ambiguous Tactics and Attitudes toward Their Use-2 • Is It All Right to Use Ethically Ambiguous Tactics? The studies summarized here indicate that there are tacitly agreed-on rules of game in negotiation. In these rules, some minor forms of untruths maybe seen as ethically acceptable and within the rules. • Deception by Omission versus Commission The use of deceptive tactics can be active or passive. The researchers discovered that negotiators used two forms of deception in misrepresenting the commonvalue issue: misrepresentation by omission and misrepresentation by commission • The Decision to Use Ethically Ambiguous Tactics: A Model The Decision to Use Ethically Ambiguous Tactics: A Model Figure 9.2 A Simple Model of Ethical Decision Making Intentions and Motives for Using Deceptive Tactics Influence Situation Identification of Range of Influence tactics Use Deceptive Tactics Yes Selection and Use of Deceptive Tactic (s) No Explanation And Justifications Consequences: 1.Impact of tactic: Does it work? 2.Self-evaluation 3.Feedback and Reaction From other Negotiator, Constituency, and Audiences 5. Why Use Deceptive Tactics? Motives and Consequences In the preceding pages we discussed at length the nature of ethics and the kinds of tactics in negotiation that might be regarded as ethically ambiguous. Now we turn to a discussion of why such tactics are tempting and what the consequences are of succumbing to that temptation. 5.1 The Power Motive • Information has power because negotiation is intended to be a rational activity involving the exchange of information and the persuasive use of that information. • In fact, it has been demonstrated that individuals are more willing to use deceptive tactics when the other party is perceived to be uniformed or unknowledgable about the situation under negotiation; particularly when the 5.2 Other Motives to Behave Unethically • The motivation of a negotiator can clearly affect his or her tendency to use deceptive tactics. (See Box 9.2 for a discussion of motives of cheaters in running ) • But the impact of motives may be more complex. Differences in the negotiators’ own motivational orientation—cooperative versus competitive--didn’t cause differences in their view of the appropriateness of using the tactics, but the negotiators’ perception of other’s 5.3 The Consequences of Unethical Conduct • A negotiator who employs an unethical tactic will experience consequences that may be positive or negative, based on three aspects of the situation: • (1) Effectiveness. Clearly, a tactic’s effectiveness will have some impact on whether it is more or less likely to be used in the future. • (2) Reactions of Others. Depending on whether these parties recognize the tactic and whether they evaluate it as proper or improper to use, the negotiator may receive a grate deal of feedback. • (3) Reactions of Self. Under some conditions, a negotiator may feel some discomfort, stress, guilt, or • 5.4 Explanations and Justifications The primary purpose of these explanations and justifications is to rationalize, explain, or excuse the behavior—to verbalize some good, legitimate reason why this tactic was necessary. • Rationalizations adapted from Bok and her treatise on lying: (1)The tactic was unavoidable. (2)The tactic was harmless. (3)The tactic will help to avoid negative consequences. (4)The tactic will produce good consequences, or the tactic is altruisucally motivated. (5)“They had it coming”,or “They deserve it,” or “I’m just getting my due”. (6)“They were going to do it anyway, so I will do it first” (7)“He started it”. (8)The tactic is fair or appropriate to the situation. 6. What Factor Shape a Negotiator’s Predisposition to Use Unethical Tactics Figure 9.3 A more complex model of decision making Individual Differences Demographic Factors Personality Characteristics Moral Development Influence Situation Intentions and Motives for Using Deceptive Tactics Identification of Range of Influence tactics Contextual Influences Use Deceptive Tactics Yes Selection and Use of Deceptive Tactic (s) No Explanation And Justifications Consequences: 1.Impact of tactic: Does it work? 2.Self-evaluation 3.Feedback and Reaction From other Negotiator, Constituency, and Audiences 6.1 Demographic Factors -1 • Sex A number of studies show that women tend to make more ethically rigorous judgment than men. Men were more likely to use some unethical judgments than women. Differences may exist in the way that man and women are perceived as ethical decision makers. Overall, female actors were perceived to be formalistic in their decision, and males perceived to be more utilitarian. • Age and Experience Older individuals were less likely than younger ones to see marginally ethical tactics as appropriate. Individuals with more work experience were less likely to use unethical tactics. 6.1 Demographic Factors-2 • Nationality and Culture It is apparent that there are cultural differences in attitudes toward ethically ambiguous tactics in negotiation, although there are not enough research findings to create a coherent overall picture. And Box 9.3 tells the complications involved in understanding ethics in cross-cultural negotiation. • Professional Orientation The finding of related researches are actually more about which role a person plays—defenders versus challenger of the status quo—than about the attorney role that they play. 6.2 Personality Differences • Competitiveness versus Cooperativeness • Machiavellianism A number of studies have shown that individuals who are strongly Machiavellian are more willing and able to tell a lie without feeling anxious about it, and more persuasive and effective in their lies. • Locus of Control Studies have generally predicted that high in internal control are more likely to do what they think is right and to feel that they had more control over producing the outcomes they wanted to achieve in a situation in which there were temptations to be 6.3 Moral Development and Personal Values • Kohlberg proposed that an individual’s moral and ethical judgments are a consequence of achieving a particular developmental level or stage of moral growth. Kohlberg proposed six stages of moral development, grouped into three levels. • The mixed findings are reasonably consistent with the growing literature that attempts to measure individual values and morality and related them to ethical 6.4 Contextual Influences on Unethical Conduct • Past Experience • Role of Incentives • Relationship between the Negotiator and the Other Party • Relative Power between the Negotiators • Mode of Communication • Acting as an Agent versus Representing Your Own Views • Group and Organizational Norms and 7. How Can Negotiator Deal with the Other Party’s Use of Deception • Ask Probing Questions Asking questions can revel a great deal of information, some of which the negotiator may intentionally leave undisclosed. • Force the Other Party to Lie or Back Off (1) “Call” the Tactic (2) Discuss What You See and Offer to Help the Other Party Change to More Honest Behaviors (3) Respond in Kind (4) Ignore the Tactic 8. Chapter Summary • In this chapter, we have discussed factors that negotiators consider when they decide whether particular tactics are deceptive and unethical. • We began by drawing on a set of hypothetical scenarios to discuss how ethical questions are inherent in the process of negotiation. Then presented four fundamental approaches to ethical reasoning and showed how each might be used to make decisions about what is ethically appropriate. • We analyzed the motives for and consequences of engaging in unethical