ENGL 6680 Syllabus - ENGL 6680 HOME

advertisement

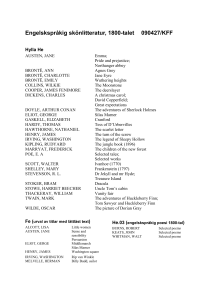

Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, and the 19th-Century Woman Writer Tuesday 5:30-7:45, Fretwell Instructor: Dr. Gargano Office: Fretwell 250F Office Phone: 704-687-0022 Office Hours: T 3-4, W 12-1 and by appointment Email: egargano@uncc.edu Website: egargano.weebly.com Texts Austen, Northanger Abbey; Pride and Prejudice; Persuasion Ann, Brontë, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre; Villette Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights Course Description: This is a theory-intensive, historically oriented seminar. For 19th century readers and critics, Jane Austen and the three Brontë sisters embodied oppositional models of “the woman author.” Charlotte Brontë mocked Jane Austen’s characters as “commonplace” creatures in “elegant but confined houses.” For some admirers of Austen, Brontë’s fiction lacked the earlier novelist’s subtlety, sophistication, and “feminine delicacy.” Along with their sister Charlotte, both Emily and Anne Brontë were also criticized for literary “coarseness,” and for taking on daring or controversial subjects supposedly unsuited to women writers. While Austen brought her form of literary realism to a high gloss, and the Brontës often mined the twin veins of literary romanticism and the gothic imagination, all four writers pushed the limits of gender and genre in intriguing ways; all four helped to alter their contemporaries’ assumptions about the novel’s possibilities and the role of the 19th century woman author. As we engage in close readings of their novels, we will also explore the numerous works of literature and film that they have inspired. Finally, we will investigate how Austen and the Brontës have been mythologized or romanticized over time, and how their literary reputations have been linked to changing critical and theoretical paradigms. Students are encouraged to explore connections among our readings in a seminar paper that they can work on, in stages, throughout the term. While our main focus is on literary texts, visual art and film will also play a role in our discussions. In addition, we will read brief selections from a range of literary historians and scholars who can further enrich our understanding of these major women novelists and their role in shaping the genre of the novel. These contextual readings will be available electronically (via email or our website), and must be completed along with our novels. Note: Please read reserve readings after completing the fiction assigned for each class period. I have placed a number of books on hardcopy reserve at the library for our class (ENGL 6680/Gargano), to help you with papers, presentations, and your bibliography. Requirements Since this class is a graduate seminar, student contributions, both oral and written, will be a major component of the course. I look forward to engaging with you in a 1 semester-long conversation about our texts, and the issues surrounding them. Vigorous class participation is expected from all students. Seminar paper due at the end of the term (70% of grade) A paper of 12-15 pages will be written in stages so that we can work individually to showcase and refine your ideas. Students will first submit an essay proposal, then an initial draft, and ultimately a final draft. We will meet in conference to discuss the initial draft of your essay. Once the essay is completed, students will have a chance to share their ideas informally with the rest of the class. Midterm: Annotated Bibliography (10% of grade) For any novel of your choice, create an annotated bibliography. Your bibliography should include at least seven scholarly essays about the novel. Annotate each scholarly essay cited with 4-5 sentences of description. Then write a one-page explanation of why you chose these essays, and why you find them to be a valuable contribution to the scholarship. 30-Minute Teaching Session (10% of grade). Working in groups of two or three, you will be responsible for leading part of a discussion of one of our texts. You may choose to concentrate on one or two specific scenes and/or passages, imagery, style, or major themes. You can offer some lecture, but you must include at least some guided discussion. Please talk to me about your discussion sessions with me at least a week before you lead the discussion. Final Exam/Presentations (10% of grade) Working in groups of two or three, you will have the opportunity to report on selected re-writings, films, continuations, or novels based on the works of Austen or the Brontes, especially those relevant to changing conceptions of the role of women. Emails A brief email response to each text is due weekly before class. Emails must be submitted to me by Monday at 5 PM the day before our class. Each email should include at least 2 questions or issues that you would like to explore in class. I’ll use your emails to address your particular interests. Emails should be short and to the point, no more than 200 words in length. Note: On occasion, I may ask you to address specific questions or issues in your emails. Individual emails are not graded, and students are excused from submitting an email when they are leading a class discussion. In addition, you may skip one other email. If you miss 3 emails, your grade will drop by 3 numerical points. Missing more emails causes a further drop in grade. Attendance Two free unexcused absences. Three absences will cause your grade to drop three points (i.e., from a numerical grade of .90 to .87. Each additional absence means another three-point drop. Five absences will result in a failing grade or withdrawal 2 from the course. Students are expected to arrive at class on time. Three late arrivals (over five minutes late) will be counted as an absence. If you do arrive late, you are responsible for notifying me after class so that you can be marked present. This policy takes effect after the first class. Plagiarism: “Intentionally or knowingly presenting the work of another as one’s own (i.e., without proper acknowledgement of the source).” Examples include “quoting from a source without citation; paraphrasing or summarizing another’s work without acknowledging the source” --UNCC Policy Statement #105: The Code of Student Academic Integrity. For more information see www.uncc.edu/unccatty/policystate Plagiarism brings severe consequences, potentially including failure of the class. 3 Tentative Reading Schedule August 19 Introductions: Images of the Female Author; Authorship & Authority; Angels in the House; Performing Gender; Who is Jane Austen, and what is she doing in our collective dreams? 26 Authoring a Tradition: Austen, Northanger Abbey Excerpts: Laughing Feminism; September 2 Authoring a Life: Austen, Pride and Prejudice (Volume I & II, or Ch. 1-42) 9 Pride and Prejudice (Volume III, or Ch. 43-end) 16 Authoring the Past: Austen, Persuasion (Volume I, or Ch. 1-12) 23 Persuasion (Volume II, or Ch. 13-end) 30 Subverting Authorship: E. Brontë, poetry (electronic document); Wuthering Heights (Volume I, or Ch. 1-14) October 7 Fall Break 14 Wuthering Heights (Volume II, or Ch. 15-end); Bibliography due 21 The Romance of Authorship: C. Brontë, Jane Eyre (Volume I, or Ch. 1-15); Essay Proposal due 28 Jane Eyre (Volumes II & III, or Ch. 16-38); November 4 Authority and Authorial Deceptions: C. Brontë, Villette (Ch.1-20) 11 Villette (Ch. 21-42) 14 Friday: Essays due to me via email by 12 midnight 18 Essay Conferences: Class canceled 25 Re-Authoring Gender: A. Brontë, Tenant of Wildfell Hall (Ch. 1-26) December 2 Wildfell Hall (Ch. 27- 53) Exam: Tuesday, 12/9, 5-7:30: Austen/ Bronte revisions & continuations Note: Some editions of our novels display volume numbers, and some don’t. This may affect the numbering of chapters. For these texts, I have indicated both types of numbering. Issues to consider in your emails for Northanger Abbey: A defense of women’s authorship; sisterhood & betrayal; the Gothic tradition; men, women, & authority; satire; class. 4 Austen and the Literary Tradition Jane Austen on Her Writing "What should I do with your strong, manly, spirited Sketches, full of Variety and Glow? - How could I join them on to the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour?" --to nephew James Edward, qted in "Biographical Notice of the Author" (1817) by Henry Austen I am fully sensible that an Historical Romance, founded on the House of Saxe Cobourg might be much more to the purpose of Profit or Popularity, than such pictures of domestic Life in Country Villages as I deal in—but I could no more write a Romance than an Epic Poem.—I could not sit seriously down to write a serious Romance under any other motive than to save my life, & if it were indispensable for me to keep it up & never relax into laughing at myself or other people, I am sure I should be hung before I had finished the first chapter. No - I must keep my own style & go on in my own way; and though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other.” --to James Stanier Clark (1816), librarian to the Prince of Wales Walter Scott on Jane Austen Also read again, and for the third time at least, Miss Austen's very finely written novel of Pride and Prejudice. That young lady had a talent for describing the involvement and feelings and characters of ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The big Bow-wow strain I can do myself like any now going, but the exquisite touch which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting from the truth of the description and the sentiment is denied to me. --from a journal entry, March 14th 1826 Charlotte Bronte on Jane Austen ``Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point. . . I had not seen Pride and Prejudice till I had read [your last letter], and then I got the book. And what did I find? An accurate daguerrotyped [photographed] portrait of a commonplace face; a carefully fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no glance of a bright vivid physiognomy, no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck [stream]. I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant but confined houses. These observations will probably irritate you. but I shall run the risk. ---from a letter of to the writer and editor George Lewes (January 12th 1848) Ralph Waldo Emerson on Austen "I am at a loss to understand why people hold Miss Austen's novels at so high a rate, which seem to me vulgar in tone, sterile in artistic invention, imprisoned in their wretched conventions of English society, without genius, wit, or knowledge of the world. Never was life so pinched and narrow. ... All that interests in any character [is this]: has he (or she) the money to marry with? ... Suicide is more respectable." 5 Reading Packet 1.Virginia Woolf on “The Angel in the House” (1931) But to tell you my story--it is a simple one. You have only got to figure to yourselves a girl in a bedroom with a pen in her hand. She had only to move that pen from left to right--from ten o'clock to one. Then it occurred to her to do what is simple and cheap enough after all--to slip a few of those pages into an envelope, fix a penny stamp in the corner, and drop the envelope into the red box at the corner. It was thus that I became a journalist; and my effort was rewarded on the first day of the following month--a very glorious day it was for me--by a letter from an editor containing a cheque for one pound ten shillings and sixpence. But to show you how little I deserve to be called a professional woman, how little I know of the struggles and difficulties of such lives, I have to admit that instead of spending that sum upon bread and butter, rent, shoes and stockings, or butcher's bills, I went out and bought a cat--a beautiful cat, a Persian cat, which very soon involved me in bitter disputes with my neighbours. What could be easier than to write articles and to buy Persian cats with the profits? But wait a moment. Articles have to be about something. Mine, I seem to remember, was about a novel by a famous man. And while I was writing this review, I discovered that if I were going to review books I should need to do battle with a certain phantom. And the phantom was a woman, and when I came to know her better I called her after the heroine of a famous poem, The Angel in the House. It was she who used to come between me and my paper when I was writing reviews. It was she who bothered me and wasted my time and so tormented me that at last I killed her. You who come of a younger and happier generation may not have heard of her--you may not know what I mean by the Angel in the House. I will describe her as shortly as I can. She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draught she sat in it--in short she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others. Above all--I need not say it--she was pure. Her purity was supposed to be her chief beauty--her blushes, her great grace. In those days--the last of Queen Victoria--every house had its Angel. And when I came to write I encountered her with the very first words. The shadow of her wings fell on my page; I heard the rustling of her skirts in the room. Directly, that is to say, I took my pen in my hand to review that novel by a famous man, she slipped behind me and whispered: "My dear, you are a young woman. You are writing about a book that has been written by a man. Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the arts and wiles of our sex. Never let anybody guess that you have a mind of your own. Above all, be pure." And she made as if to guide my pen. I now record the one act for which I take some credit to myself, though the credit rightly belongs to some excellent ancestors of mine who left me a certain sum of money--shall we say five hundred pounds a year?--so that it 6 was not necessary for me to depend solely on charm for my living. I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. My excuse, if I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self-defence. Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. For, as I found, directly I put pen to paper, you cannot review even a novel without having a mind of your own, without expressing what you think to be the truth about human relations, morality, sex. And all these questions, according to the Angel of the House, cannot be dealt with freely and openly by women; they must charm, they must conciliate, they must--to put it bluntly--tell lies if they are to succeed. Thus, whenever I felt the shadow of her wing or the radiance of her halo upon my page, I took up the inkpot and flung it at her. She died hard. Her fictitious nature was of great assistance to her. It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality. She was always creeping back when I thought I had despatched her. Though I flatter myself that I killed her in the end, the struggle was severe; it took much time that had better have been spent upon learning Greek grammar; or in roaming the world in search of adventures. But it was a real experience; it was an experience that was bound to befall all women writers at that time. Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer. Woolf was responding in part to a lengthy and famous Victorian poem by Coventry Patmore, entitled The Angel in the House (1st version 1865). An excerpt follows: Her disposition is devout, Her countenance angelical; The best things that the best believe Are in her face so kindly writ The faithless, seeing her conceive, Not only heaven, but hope of it. Her modesty, her chiefest grace. . . How potent to deject the face Of him who would affront its pride! Wrong dares not in her presence speak, Nor spotted thought its taint disclose. . . 2. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble In what senses. . . is gender an act? As in other ritual social dramas, the action of gender requires a performance that is repeated. This repetition is at once a reenactment and reexperiencing of a set of meanings already socially established; and it is the mundane and ritualized form of their legitimation. Although there are individual bodies that enact these significations by becoming stylized into gendered modes, this “action” is a public action. There are temporal and collective dimensions to these actions, and their public character is not inconsequential; indeed, the performance is effected with the strategic 7 aim of maintaining gender within its binary frame—an aim that cannot be attributed to a subject, but, rather, must be understood to found and consolidate the subject. Gender ought not to be construed as a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts follow; rather, gender is an identity tenuously constituted in time, instituted in an exterior space through a stylized repetition of acts. The effect of gender is produced though the stylization of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self. This formulation moves the conception of gender off the ground of a substantial model of identity to one that requires a conception of gender as a constituted social temporality. Significantly, if gender is instituted through acts which are internally discontinuous, then the appearance of substance is precisely that, a constructed identity, a performative accomplishment which the mundane social audience, including the actors themselves, come to believe and to perform in the mode of belief. Gender is also a norm that can never be fully internalized; “the internal” is a surface signification, and gender norms are finally phantasmatic, impossible to embody. . .The abiding gendered self will then be shown to be structured by repeated acts that seek to approximate the ideal of a substantial ground of identity, but which, in their occasional discontinuity, reveal the temporal and contingent groundlessness of this “ground.” 3. Excerpt from Audrey Bilger, Laughing Feminism (1998) Women and comedy were controversial topics in eighteenth-century England. The debates revolved around questions of morality and control: Would women’s freedom lead to promiscuous behavior? Would unchecked comedy ridicule improper targets? Although not necessarily linked in the public imagination, women and comedy were both seen as potentially disruptive to the social order, and many pens combined to forestall any riotousness. But. . .wit and humor seek out ways of escaping from confinement, of breaking down barriers, and of turning the tables on those who attempt to suppress them. Thus, when we find prohibitions against women’s wit and humor cropping up in eighteenth-century writings, we should pay attention to the boundaries being put in place and ask whether closed doors, shut casements, and tipped keyholes were able to contain women’s laughing spirits. In order to understand more fully the rebelliousness inherent in . . .[women’s] comic writing. . .we need to consider the cultural milieu in which they wrote, in particular those views and values that exerted ideological pressure on women’s self-expression. Unless we recognize the efforts that were made to control women’s behavior, we are apt to misunderstand the specific forms their comedy takes and thus overlook some of their most trenchant social criticism. . . . Suspicions regarding laughter’s sexuality led John Gregory, in his extremely popular conduct book [1774], to advise that young women beware of getting carried away by group laughter: “Sometimes a girl laughs with all the simplicity of unsuspecting innocence, for no other reason but being infected with other people’s laughing: she is then believed to know more than she should do” (59). Whether the laughing young women actually “knows” anything about sex is beside the point; laughter reveals an active understanding that belies innocence. Such restrictions on female laughter would have made it difficult for an eighteenth-century women to exercise comic talents in public when, even in private, 8 she was urged to be self-conscious about her wit and humor. With the installation of the nuclear family as a cultural icon, to which female virtue served as handmaiden, female laughter came to represent a threat to the domestic order, an abandonment to pleasure that had revolutionary overtones. Laughter calls attention to itself in an aggressive, forceful manner, and, within the confines of decorum, it suggests an insubordination in proportion to its volume. According to conduct-book writers. . .domestic harmony required that a woman govern her sense of humor and her sexuality. Either factor, if not curbed, could compromise the safety of the domestic realm, one with insurrection, the other with illegitimate offspring. 4. Diane Long Hoeveler, Gothic Feminism: The Professionalization of Gender from Charlotte Smith to the Brontes (1995) Major eighteenth- and nineteenth-century female writers like Smith, Radcliffe, Austen, Dacre, Shelley, and the Brontes all exploited in their works the appearance of their compliance with traditional domestic values. But we should not confuse such a facade with their elided purposes. The female gothic writer attempted nothing less than a redefinition of sexuality and power in a gendered, patriarchal society; she fictively reshaped the family, deconstructing both patrimonialism (inheritance through the male) and patrilineality (naming practices) in the process. In short, she invented her own peculiar form of feminism. And in challenging both codes of masculine privilege, she possessed her rightful fictional birthright: access to the untrammeled desire and energy to reshape her version of “reality.” In the female gothic work she creates what she thinks are alternative, empowering femalecreated fantasies. In her triumphant act of self-creation she rejects her subjugation and status as “other,” whether object or absence, and she refuses to subscribe passively to confining male-created ideologies of the “woman as subject.” She proffers instead victim feminism as a female created ideology, mixing one part hyperbolic melodrama with one part Christian sentimentalism, and creating a heady brew that promised its readers the ultimate fantasy: their socially and economically weak positions could actually be the basis of their strength. The meek shall inherit the gothic earth; evil is always destroyed because it deserves to be. The buried reality that lies not very far below the surface of the female gothic is the sense that middle-class women can only experience the male-identified patriarchal-capitalist home as either a prison or an asylum. A woman is reduced in such a home to the status of an object, decorative or functional depending on her husband’s class. Life in such a home and the identity it conferred on a woman constitute the nightmare at the core of the female gothic, and victim feminism. But the home created by Emily and Valancourt at the conclusion of The Mysteries of Udolpho [Radcliffe’s most famous novel], for instance, is not a patriarchally marked home. Valancourt appears to be living at La Vallee on an extremely tenuous basis, having been perceived by Emily and her friends as damaged goods after his disastrous foray in Paris. Acceptably tamed gothic husbands exist on very short leashes, and it is Emily and her sister heroines who hold the power in these new 9 households. Having traced the ravaging patriarch out of existence, the gothic feminist lives in her new domicile with her ritualistically wounded husband, a quasi sibling who, like her, has barely survived his brush with the oppressor and has emerged chastened.... (Introduction, 19-20). 5. Candleglow Gothic Romance Guidelines 2003 With the popularity of the dark hero again on the upswing, Love Spell has brought back a beloved mainstay of romance: the Gothic. Set against dark backdrops such as Transylvanian castles and keeps on deserted moors, these romances are mainly told from the heroine's point of view. The books most often revolve around a naive heroine who is placed in close proximity with-and often under the protection of-a hero of whom she knows little and whom she suspects or even fears. However, these enigmatic men are often those who claim our hearts and seduce our bodies, and the unveiling of their mysteries is part of the path to true love. The challenge in writing a Gothic for Candleglow, along with creating an evocative, ominous setting, is maintaining the powerful sexual attraction the heroine feels for the hero-despite any questions she might have regarding her safety and the trustworthiness of her lover. As always, the focus should remain on the development of the relationship between the hero and heroine, and should not be shifted to other plot concerns. Although these romances can contain paranormal elements, they should be strictly historical in regard to time period and as sensual as possible. 10