Chapter 5 - Aufinance

advertisement

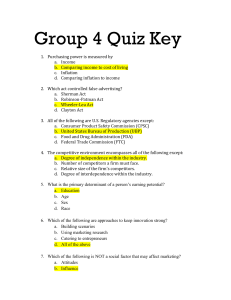

CHAPTER 5 Interest Rate Determination ©Thomson/South-Western 2006 1 Interest Rates Interest rates are important because they affect: the level of consumer expenditures on durable goods; investment expenditures on plant, equipment, and technology; the way that wealth is redistributed between borrowers and lenders; the prices of such key financial assets as stocks, bonds, and foreign currencies; the monthly payments on households’ car loans and home mortgages, and income earned by households on savings accounts, certificates of deposit, various types of bonds, and money market mutual fund shares. For our purposes, “interest rate” and “yield” are used interchangeably. 2 Real and Nominal Interest Rates The nominal interest rate is the stated interest rate, unadjusted for inflation. The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate adjusted for inflation. The real interest rate is the actual interest rate that would prevail in a hypothetical world of zero inflation. 3 Present Value: Interest Rates And Security Prices Present Value (PV), Interest Rates(i), and Securities Prices interrelate. The present value is the discounted value of a payment (or stream of payments) to be received at some point in the future. Simple one-year present value: PV = FV / (1+i) The future value is the interest-adjusted value of a payment (or payments) to be made now (or in the future) at some point in the future. Simple one-year future value: FV = PV (1+ i) The price of any security is the present value at a given interest rate of the future payments expected to be made by the security issuer PV (or price) = R1/(1+i) + R2 / (1+i)2 + R3 / (1+i)3 + … + Rn / (1+i)n 4 Fig 5-1 5 Interest Rates and Security Prices Interest rates and bond (or any debt instrument) prices are inversely related. Interest rate increases decrease bond prices (PV). Interest rate decreases increase bond prices (PV). At interest rate, i, a bond that pays F at maturity with coupon payments C1, C2, C3, …,Cn is worth PV = C1/(1+i) + C2/(1+i)2 + C3(1+i)3 + … + (Cn+ F) / (1+i)n Suppose a 5%, 5-year bond pays $1000 at maturity with annual coupons of $50. If interest rates rise to 6% then price falls to $965.34 $50/1.06 + $50/(1.06)2 + $50/(1.06)3 + ($50 + $1,000) / (1.06)4 6 The Loanable Funds Model Of Interest Rates Economists and financial analysts use the loanable funds model to forecast interest rates. The interest rate is the price paid for the right to borrow and use loanable funds. Borrowers demand funds, Savers supply funds. 7 Individual Sources of Supply and Demand for Loanable Funds in the United States Sources of Supply personal saving business saving government budget surplus bank loans foreign lending in the U.S. Sources of Demand household credit purchases business investment spending government budget deficit foreign borrowing in the U.S. 8 Figure 5-2 9 The Loanable Funds Model The interest rate: is the reward for saving; works to counteract the human trait of time preference. Supply slopes upward. Household saving is relatively insensitive to the interest rate. Bank lending varies directly with the interest rate because profitmaximizing banks more aggressively seek out and grant loans as rates rise. Holding foreign interest rates constant, an increase in U.S. rates attracts additional funds to U.S. financial markets from abroad. Demand slopes downward. Lower car/home/furniture loan rates reduce monthly payments, thereby increasing these items’ affordability. Lower rates induce investment in plant, equipment, inventories, and nonresidential real estate. Lower interest rates in the United States induce foreigners to step up borrowing in the U.S. 10 Factors Shifting Supply and Demand for Loanable Funds Inflation Expectations Federal Reserve Policy The Business Cycle Federal Budget Deficits (Surpluses) 11 Inflation Expectations Interest rates rise in periods during which people expect inflation to increase. Interest rates typically fall when people expect inflation to decline. The loanable funds framework can easily explain this: People are less willing to lend funds because they expect the real value of the principal loaned out to erode more rapidly if inflation increases. People are much more willing to borrow because they expect the real value of the debt incurred to fall more rapidly as inflation rises. 12 The Fisher Hypothesis A formula linking nominal (actual) interest rates and expected inflation: i = r + e e represents the expected inflation rate is the extent to which nominal interest rates adjust to each one percentage-point increase in the expected inflation rate The Fisher Hypothesis: strong form: =1 inflation neutrality weak form: >0 Economists agree that inflation expectations powerfully influence the level of interest rates, especially long-term rates. 13 The Fundamental Forces Driving Real Interest Rates Marginal productivity of capital: rate of return expected by firms from purchase of an additional unit of capital goods Rate of time preference: extent to which people prefer present goods over future goods Federal Reserve policies The federal government budget Business cycle conditions 14 Empirical Evidence on the Fisher Hypothesis Empirical research indicates that the sensitivity of interest rates to inflation appears to have increased sharply in the post-World War II era. Before the 1940s, financial markets do not appear to have responded to inflation. In the past 50 years, interest rates have exhibited a definite sensitivity to the outlook for inflation. 15 Federal Reserve Policy To stimulate the economy, the Fed implements measures that: encourage banks to expand loans, thereby boosting the money supply moving the supply curve of loanable funds rightward, which reduces interest rates. To restrain economic activity, the Fed implements actions that: force banks to reduce their lending, thereby curtailing the money supply, moving the supply curve of loanable funds leftward and thus driving up interest rates. The Federal Reserve has considerably more direct influence on short-term interest rates than on long-term rates. 16 The Business Cycle Interest rates have historically been strongly pro-cyclical: rising during the expansion phase of the business cycle and falling during periods of economic contraction. This pattern is most evident in short-term interest rates. 17 Federal Budget Deficits (or Surpluses) Intuitively, an increase in the federal budget deficit should raise interest rates. An increase in borrowing by the federal government implies a rightward shift in the demand curve for loanable funds. Most economists agree that deficits lead to higher interest rates. Some disagree and argue: that the size of the U.S. deficit is small in relation to the total pool of worldwide financial capital, and that a relationship between the federal budget deficit and saving behavior of individuals interferes with any such direct relationship between the size of the budget deficit and interest rates. The Ricardian Equivalence proposition suggests that people will offset deficits with greater savings to pay future taxes. 18 Major Interest Rate Movements, 1960-2003 1960-1965 Low inflation, low bond yields. 1965-1981 Vietnam(66-69), oil price shocks (73-79), rapid inflation (78-80), Fed policy increased interest rates to eradicate inflation (80-81) 1980-2003 inflation fell, expected inflation Fell worldwide recession (81-83) moderate inflation (82-90) sluggish recovery from 1990 recession->low short term interest rates low inflation (91-2000) low long and short term rates (00-03) 19 Real Interest Rates: Ex Ante vs Ex Post Expected or ex ante real rate r ex ante = i - e Realized or ex post real rate r ex post = i - The expected or ex ante real interest rate is of CRITICAL importance because investors act upon this information. 20 Two Measures of Ex Ante Real Interest Rates Before Tax r = i - e After Tax rat = i (1-t) - e Where t is the marginal income tax rate 21 The Historical Behavior of Expected Real Interest Rates The expected real interest rate is not constant over time. 1970s low 1980s high 1990s intermediate 2000-2004 very low (some negative) 22 The High Rates of the 1980s The Fed maintained tight money policies in 1980-81. Large federal budget deficits emerged after 1981 (tax cuts and defense buildup). Pro-business policies (cuts in business taxes, deregulatory actions), increased the expected returns from capital expenditures, boosting demand for funds by business. Lower real energy prices increased demand for energy intensive capital goods. 23 1970s Low Real Rates of the 1970s and 2000s stimulative monetary policy expected returns from capital goods were low small budget deficits 1995-2000 technological innovations in information systems, telecommunications, and other areas led to a sharp increase in the expected returns from capital major swing from large federal budget deficits to large surpluses relatively low inflation made possible by surging productivity and a strong U.S. dollar internationally stimulative monetary policy 2001-2004 stimulative monetary policy recession low business and consumer confidence 24