Energy Changes in Chemical Reactions Teacher

advertisement

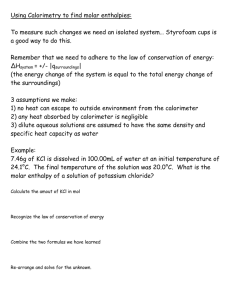

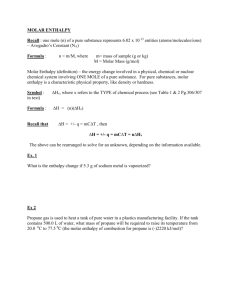

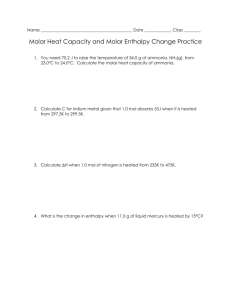

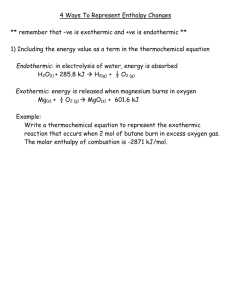

Chemistry 30 Unit 2: Energy Changes in Chemical Reactions Teacher 1 Energy: In science, energy is often defined as “the ability to do work” or “the capacity to produce change”. Potential energy is energy possessed by a body because of its position Kinetic energy is the energy of motion o Temperature measures the average kinetic energy of the substance, not the total energy, since potential energy is not measured. o Temperature is measured in Celsius or Kelvin. To change Celsius to Kelvin add 273 and to change Kelvin to Celsius, subtract 273. Ex. Determine the temperature change in Celsius and in Kelvin if a container of water cools from 98oC to 23oC. ∆t = tf – ti = 23oC – 98oC= -75oC ∆t = tf – ti =296K – 371K = -75K Notice that the change in temperature is the same value if we use Celsius OR Kelvin. Thermal energy is the sum of the kinetic energy and potential energy an object has. o If you have a cup of water at 80oC and a bathtub of water at 30oC, which has more KE and which has more PE? Which would have more thermal energy? Cup has more kinetic energy Bathtub has more potential energy Bathtub has more thermal energy o Heat energy is the transfer of thermal energy from one object to another. Heat always flows from the warmer object to the colder object. The transfer of energy can be detected by measuring the resulting temperature change. o When energy is transferred to molecules, the molecules move faster, hit each other more often, and transfer more energy to one another. Radiant energy is energy transmitted through space as electromagnetic waves. The most familiar form is light. Chemical energy is the energy necessary to keep atoms joined by chemical bonds. During a chemical reaction, chemical energy may be stored, released as heat, converted to other forms of energy, or converted to work. Whatever changes take place, energy is always conserved. It is a fundamental law of nature (the law of conservation of energy) that energy can neither be created nor destroyed but may be converted from one form to another. Energy in the universe is constant. The unit used to measure energy is the Joule. 1J = 1𝑘𝑔∙𝑚2 𝑠2 1 J = 2.78 x 10-7 kW∙h 1 J = 2.39 x 10-4 kcal 2 Heat: Heat is thermal energy in transit. If you touch something hot, energy is transferred from the hot object to your hand. If you touch something cold, heat energy passes from your hand to the cold object. We should only use the term heat to describe energy that is flowing from one substance to another because of a temperature difference. Specific Heat: The specific heat of a substance is the amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of a substance by 1 degree Celsius or 1 kelvin. Units used to measure specific heat = J•g−1•K−1 or J•g−1•°C−1 or 𝐽 𝑔∙𝐾 or 𝐽 𝑔∙℃ Different substances have different specific heats, this is because substances vary in their ability to store energy, and they also gain or lose heat at different rates. Ex. Comparing water to aluminum. It takes 4.18 J to raise the temperature of liquid water 1°C, whereas for aluminum only 0.903 J are required. For the same increase in temperature, liquid water requires over 4 times as much energy as the same mass of aluminum. Why do you think water would be used as a coolant instead of another liquid (like mercury)? Water can absorb a large quantity of heat with only a slight rise in temperature. Water has the greatest heat capacity of all liquids. Substance Specific heat (J/g·°C) Al(s) 0.903 Fe(s) 0.449 Hg(l) 0.139 H2O(l) 4.184 O2(g) 0.917 He(g) 5.19 CO2(g) 0.843 Substance Specific heat (J/g·°C) Au(s) 0.129 Na(s) 1.24 Cu(s) 0.385 H2(g) 14.4 H2O(g) 1.86 Ag(s) 0.235 H2O(s) 2.087 Heat Required to Change Temperature: The formula to calculate heat required to change the temperature of a substance is: Q = (m) (c) (∆t) Where Q= heat amount (Joules) m = mass (g) ∆t = tfinal – tinitial *Losing heat would give you a negative Q* c = specific heat capacity (J/g∙oC) ∆t = temperature change (oC or K) 3 Ex. Determine the heat required to raise the temperature of 100.0 mL of water from 298.0 K to 373.0 K. Q = (m) (c) (∆t) Q = (m) (c) (∆t) Q=? m = 100g (100mL = 100g of water) c = 4.18J/g∙K ∆t = tf – ti = 373.0 K − 298.0 K = 75.0 K = (4.18 J/g•K)(100 g)(75.0 K) = 31.4 kJ Heat capacity: Heat capacity is the heat energy required to raise the temperature of a given quantity of a substance by one degree Celsius or one kelvin. *Heat capacity is not the same as SPECIFIC heat capacity* Heat capacity (J/°C) = specific heat × mass ∴ Heat Capacity = Q/∆t Ex. Determine the heat capacity of 1 cup of water (250mL). *Remember the density of water is ~1g/mL* Heat capacity = specific heat x mass = (4.18J/g∙K)(250g) = 1045J/K or 1045J/oC Ex. Calculate the heat capacity of a piece of iron that releases 3500J of heat into a container of water, and the temperature of the iron drops from 100oC to 24oC. Heat Capacity = Q/∆t = (-3500J/[24oC – 100oC]) Heat Capacity = 46J/oC Molar Heat Capacity: Molar heat capacity of a substance is the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of one mole of a substance by one Celsius degree or one kelvin. Molar heat capacity (J/mol•°C) = specific heat × molar mass Ex. Calculate the molar heat capacity of water, given that the specific heat of water is 4.18 J/g•°C. The molar mass of water is 18.02 g/mol Molar heat capacity = specific heat x molar mass = 4.18 J/ g•°C × 18.02 g/mol = 75.3 J/mol•°C Heat Capacity Assign 4 Molecular Motion: There are three types of motion that molecules undergo: Translational Motion: Molecules are free to move along linear pathways from one place to another Rotational Motion: When a molecule rotates about an axis through its center of mass. Vibrational Motion: molecules oscillate along the direction of a bond. Comparing types of motions among solids, liquids and gases: Phase Translational Rotational Vibrational Gas Free Free Free Liquid Restricted Restricted Free Solid Absent Very Restricted Free Heat Capacities of gas molecules: Monatomic gases such as helium and neon have the lowest molar heat capacity o Diatomic gases such as hydrogen and nitrogen have higher molar heat capacities o Have only translational motion since there is no bond about which to rotate or on which to vibrate, therefore adding heat makes the atoms move faster, which increases the temperature. Have vibrational and rotational motion as well as translational motion, thus requiring more energy. Diatomic gases have similar heat capacities. Triatomic gases such as water vapour and carbon dioxide have even higher heat capacities o These molecules can vibrate and rotate in more ways than diatomic gases, thus requiring even more energy. 5 Enthalpy: Enthalpy is defined as the heat content in a chemical reaction or physical process. It is symbolized by the letter H. The heat content if a substance cannot be measured directly. Instead, we measure enthalpy difference between the initial and final states. A chemical reaction undergoes a change in enthalpy when the reaction either releases energy to the surroundings or absorbs energy from the surroundings. This heat change is called the enthalpy of reaction and is symbolized by ∆H. A thermochemical equation is written with the value of ΔH included: CuCl2(s) Cu(s) + Cl2(g) ΔH = −220.1 kJ or CuCl2(s) + 220.1 kJ Cu(s) + Cl2(g) Ex. The exothermic reaction of gaseous hydrogen and oxygen at constant pressure releases 241.8 kJ of heat energy for every mole of water vapour formed. Write the thermochemical equation for the production of one mole of water vapour. H2O(g) H2(g) + ½ O2(g) ΔH = −241.8 kJ/mol Exothermic and Endothermic Reactions: In a chemical reaction, the chemical components involved in the process are known as the system. Everything outside the system then becomes the surroundings. Since energy is always conserved, energy lost by the system must be absorbed by the surroundings. Similarly, energy absorbed by the system must come from the surroundings. A reaction in which the system releases heat to the surroundings is known as an exothermic reaction. If the system absorbs heat from the surroundings, it is an endothermic reaction. Exothermic Reactions Endothermic Reactions Enthalpy of products is less than enthalpy of reactants Hproducts < Hreactants Energy is released ∆H is negative Less energy is needed to break bonds than the energy that is released when bonds form Enthalpy of reactants is less than enthalpy of products Hreactants < Hproducts Energy is absorbed ∆H is positive More energy is needed to break bonds than the energy that is released when bonds form 6 Research into the Thermochemistry of Hot and Cold Packs *Adapted from Exp 2 of Chen 115.3 Laboratory Manual 2005-2006* Purpose: To develop a prototype hot or cold pack using a dissolved salt that produces an exothermic or endothermic process. Background Information: In a chemical reaction where there is an energy change, heat can either be released or absorbed by the reaction. If energy (in the form of heat) is released into the surroundings, the surroundings get warmer. This is known as an exothermic reaction. If heat is absorbed from the surroundings, the surroundings get cooler. This is known as an endothermic reaction. The amount of heat transferred between a system and its surroundings (at constant pressure) is represented by the symbol ∆H and called enthalpy. Exothermic processes have a negative ∆H and endothermic have a positive ∆H. In this lab you will be working with a research team to develop either a hot pack or a cold pack. If you choose to develop a hot pack, you must create one that will reach a maximum temperature of 45oC. If you choose a cold pack the minimum temperature it must reach is 5oC. The way you will develop your hot or cold pack is by dissolving either CaCl2 or NH4NO3 in 100mL of water. Since dissolving CaCl2 in water is an exothermic process, it would increase the temperature of the water. Dissolving NH4NO3 in water is an endothermic process, so it would cool the water by absorbing the heat from the water. Before you can start developing your hot/cold pack, you must calculate the appropriate amount of salt to dissolve in the water, so you know where to begin. 1.00 mole of CaCl2 releases 82.9KJ of heat energy when dissolved in water (∆Hosoln= -82.9KJ/mole) and 1.00 mole of NH4NO3 absorbs 25.7KJ of heat energy when dissolved in water (∆Hosoln= +25.7KJ/mole). In this lab, in order to determine the amount of salt needed to raise/lower the temperature you will need to try several different amounts of salts. Since you will be changing the amount of salts, this is the variable in the experiment and should be the only thing you change (in order to accurately evaluate the data). Everything else in the experiment should remain constant. Procedure: 1. Complete the beginning of your formal lab report (up to the data/observations section- don’t forget your hypothesis!). 2. Gather a team of 3 or 4 people to perform this experiment with. Determine whether you will create a hot or cold pack. 3. Calculate the amount of heat energy that the water needs to release/absorb to lower/raise the temperature of 100mL of water to the appropriate temperature. Remember the specific heat of water is 4.184J/goC. This means that is takes 4.184J of energy to raise the temperature of 1g of water by 1oC. The density of water at 20oC is 0.998g/mL. The initial temperature we will use for these calculations is 20oC. 4. Calculate the amount of salt you will need to use to raise/lower the temperature of the water to the desired value. To do this, first convert the molar enthalpy of solution to enthalpy in terms of heat 7 energy released or absorbed by 1.00g of each salt (divide the molar enthalpy value by the molar mass of the salt). This value is the amount of heat absorbed/released by 1.00g of salt dissolving in water. Use this value to determine the amount of salt needed to release/absorb the amount of energy you calculated in step three. 5. Depending on the size of your group, choose 6-8 different amounts of solid to use for this experiment (the amount you calculate, 2 or 3 smaller amounts and 3 or 4 larger amounts using 5g increments). The largest amount used should be less than 60g. Prepare your observations section of your lab report as follows: State whether your group will be creating a hot or cold pack. Salt used: Appearance: Mass of _____________ (g) Initial Temperature of H2O Ti (oC) Max/Min Temperature of Solution Tm (oC) Person who made the measurements Change in temperature ∆T (oC) Prototype Data: Initial Temperature of Water: Temperature Change Required: Mass of ___________ Required: Final Temperature of Water: 6. Each member of your group will choose 2 of the 6-8 selected amounts of solid and complete the following steps. Complete the observations section of your lab report using the data your team collects. a. In a beaker, weigh the solid to the nearest 0.1g. Remember to try to keep as many variables constant as possible. b. Using a graduated cylinder, measure out 100mL of distilled water. Record the initial temperature of the water (remember to always estimate one digit). c. Add the water to the solid and stir (DO NOT USE THE THEMOMETER TO STIR THE SOLUTION). Observe the temperature increase/decrease and record the maximum/minimum temperature, Tm (Note: this will note be the final temperature, as the temperature of the room will warm/cool the solution after it reaches the max or min). 7. On graph paper, plot ∆T (y-axis) vs. mass of solid (x-axis) in each of the 6-8 trials. Each team member should make their own graph. The plot should give a straight line. 8. Create a prototype pack: Measure the initial temperature of the water to be used for the prototype pack. Determine the ∆T required to change the temperature to 45/5oC. From the graph you created, determine the weight of solid you need to make the hot/cold pack. 9. Place the experimentally determined amount of solid (from the graph) into a Ziploc bag. Pour the water into a sandwich bag (new bag), close the bag with a small rubber band and cut off the excess bag. Place 8 the sealed packet of water into the Ziploc bag, remove as much air as possible and seal the Ziploc bag. Be sure the bag is sealed completely. 10. Activate the hot/cold pack. WARNING: The bag may break open. If the concentrated solution gets on your skin, be sure to wash it off immediately with lots of water. 11. Determine the final temperature of the hot/cold pack by wrapping it around the end of the thermometer. Analysis: Write a paragraph that explains why dissolving a salt in water changes the temperature of the water. 1. Describe how well the prototype worked. Did it perform as planned? If not explain why. If you think further research could be completed, explain what that might be. 2. Explain why there was a difference observed between the calculated theoretical amount of chemical required, and the amount determined experimentally. 3. Explain why there was a difference observed (if you saw a difference) between the expected final temperature and the actual final temperature of the hot/cold pack. 4. What would you expect to observe if you used a finely powdered solid rather than pelletized solid? Would the mass of solid required change? 5. What do you expect would happen if you used the same amount of solid but used 50mL of water in your hot/cold pack instead of 100mL? Explain. Conclusion: Summarize your results from this lab. 9 Types of Enthalpy Equations: Enthalpy of Formation Equations o Each equation shows the forming of one mole of product from its elements and also contains the loss or gain of heat energy when the compound is formed. Enthalpy of Combustion Equations o Each equation shows the burning of one mole of substance in O2 and includes a heat term. The enthalpy of combustion equation is always has a loss of heat so ∆H is negative Enthalpy of Solution Equations o Each equation shows the dissolving on one mole of compound in water and includes a heat term. Enthalpy of Vaporization Equations o Each equation shows the energy involved in changing one mole of liquid to a gas at its boiling point. Enthalpy of Melting Equations. o Each equation shows the energy involved in changing one mole of solid to a liquid at its melting point. Bond Energy & Enthalpy of Formation: Atoms in molecules or formula units are held together by the electrons being attracted to the nuclei. These bonds can be easily broken by adding energy. This amount of energy is known as bond energy. Ex. H-H + 436.4kJ 2H When a bond between two hydrogen atoms break, it requires 436.4kJ of energy to occur. Alternatively, if 2 hydrogen atoms where to bond, 436.4kJ of energy would be released. 2H H-H + 436.4kJ Bond Energies at 298K Bond energies can be used to determine whether heat will be released or absorbed and how much when a mole of a compound forms from its elements. Bond energies are given in units kJ and this represents the amount of energy released/absorbed per mole of substance. Bond H-N H-O H-S H-P H-H H-F H-Cl H-Br H-I C-H C-C C=C C≡C C-N Bond Energy (KJ∙mol-1) 393 460 368 326 436.4 568.2 431.9 366.1 298.3 414 347 620 812 276 Bond C=N C≡N C-O C=O C-P C-S C=S N-N N=N N≡N N-O N-P O-O Bond Energy (KJ∙mol-1) 615 891 327 804 263 255 477 393 418 941.4 176 209 142 Bond O=O O-P O=S P-P P=P S-S S=S F-F Cl-Cl Br-Br I-I C-Cl N-F Bond Energy (KJ∙mol-1) 498.7 502 469 197 489 268 352 150.4 242.7 192.5 151.0 326 275 10 Ex. Assume the following reaction takes place in a series of steps and energy is absorbed when bonds break and released when bonds form. Determine whether the reaction is endothermic or exothermic, and the amount of energy released or absorbed. H2 + Cl2 2HCl Step 1: H2 2H (bond breaks ∴ absorbs 436kJ of energy): H2 + 436kJ 2H Step 2: Cl2 2Cl (bond breaks ∴ absorbs 242kJ of energy): Cl2 + 242kJ 2Cl Step 3: H + Cl HCl (bond forms ∴ releases 431kJ of energy. This occurs twice so 862kJ is released) 2H + 2Cl 2HCl + 826kJ To determine final reaction we add these three steps together and cancel anything that occurs in reactants and products: H2 + 436kJ 2H Cl2 + 242kJ 2Cl 2H + 2Cl 2HCl + 862kJ H2 + Cl2 + 678kJ-678kJ 2HCl + 862kJ-678kJ Final Reaction: H2 + Cl2 2HCl + 184kJ ∴ exothermic and ∆H = - 184kJ for the formation of one mole of hydrochloric acid. We have now used bond energies to determine the amount of energy released when 1 mole of a compound is formed from its elements. This is known as the enthalpy of formation. See Bond Energies Assignment Enthalpy of Formation and Hess’s Law: The standard enthalpy of formation of a substance is the loss or gain in heat energy when one mole of the substance is formed from its elements in their standard states, ΔH°f. o The superscript ° indicates that the value of ΔH is measured when all substances are in their standard states. o The subscript f indicates that the energy is associated with the formation of one mole of a compound from its elements in their standard states. o The enthalpy of formation for different compounds is found using the bond energy breaking/formation, just like we did in the last assignment. The more negative ΔH°f, the more stable the compounds, because these compounds require a lot of energy to break the bonds. Many chemical reactions occur in steps. For example, when carbon is burned in the presence of excess oxygen, carbon dioxide is produced. In this reaction 393.5 kJ of heat energy is liberated for every mole of carbon used. This means that the enthalpy change for the reaction is −393.5 kJ/mol. CO2(g) C(s) + O2(g) ΔH = −393.5 kJ OR (1) (2) CO(g) C(s) + ½ O2(g) CO2(g) CO(g) + ½ O2(g) CO2(g) C(s) + O2(g) ΔH = −110.5 kJ ΔH = −283.0 kJ ΔH = −393.5 kJ The end result is the same whether it is formed in a one-step reaction or in a multi-step process. This is an illustration of Hess’s Law of Constant Heat Summation: The change in enthalpy for a chemical reaction is constant, whether the reaction occurs in one step or several. 11 *When elements are formed, there is no change in enthalpy so ∆H is 0 kJ/mol* Substance ΔHf (kJ/mol) Substance ΔHf (kJ/mol) Al(s) Al2O3(s) Br2(l) HBr(g) Ca(s) CaCO3(s) CaCl2(s) C(s) (graphite) C(s) (diamond) CCl4(l) CCl4(g) CHCl3(l) CH4(g) C2H2(g) C2H4(g) C2H6(g) C3H8(g) C6H6(l) CH3OH(l) C2H5OH(l) CH3CO2H(l) CO(g) CO2(g) COCl2(g) CS2(g) CS2(l) Cl2(g) HCl(g) Cr(s) CrCl3(s) Cu(s) CuO(s) CuCl(s) CuCl2(s) F2(g) HF(g) He(g) H2(g) H2O(l) H2O(g) H2O2(l) Fe(s) FeO(s) Fe2O3(s) Fe3O4(s) FeCl2(s) FeCl3(s) FeS2(s) (pyrite) Pb(s) 0 −1675.7 0 −36.4 0 −1206.9 −795.8 0 +1.90 −135.4 −96.0 −134.5 −74.8 +226.7 +52.3 −84.7 −103.8 +49.0 −238.7 −277.7 −484.5 −110.5 −393.5 −218.8 +117.4 +89.70 kJ 0 −92.3 0 −556.5 0 −157.3 −137.2 −220.1 0 −271.1 0 0 −285.8 −241.8 −187.8 0 −272.0 −824.2 −1118.4 −341.8 −399.5 −178.2 0 PbCl2(s) Mg(s) MgCl2(s) MgO(s) Hg(l) HgS(s) Ne(g) N2(g) NH3(g) N2H4(l) NH4Cl(s) NH4NO3(s) NO(g) NO2(g) N2O(g) N2O4(g) HNO3(l) O(g) O2(g) O3(g) P4(s) (white) P4(s) (red) PH3(g) PCl3(g) P4O6(s) P4O10(s) H3PO4(s) K(s) KCl(s) KClO3(s) KOH(s) Ag(s) AgCl(s) AgNO3(s) Na(s) NaCl(s) NaOH(s) Na2CO3(s) S(s) (rhombic) S(s) SF6(g) H2S(g) SO2(g) SO3(g) H2SO4(l) Sn(s) (white) Sn(s) (grey) SnCl2(s) SnCl4(l) −359.4 0 −641.3 −601.7 0 −58.2 0 0 −46.1 +50.6 −314.4 −365.6 +90.3 +33.2 +82.1 +9.2 −174.1 +249.2 0 +142.7 0 −70.4 +5.4 −287.0 −2144.3 −2984.0 −1279.0 0 −436.7 −397.7 −424.8 0 −127.1 −124.4 0 −411.2 −425.6 −1130.7 0 +278.8 −1209.0 −20.6 −296.8 −395.7 −814.0 0 −2.1 −325.1 −511.3 12 Finding ΔH for an Equation (Hess’s Law cont.): If two or more thermochemical equations are added to give a final equation, then the enthalpies can be added to give the enthalpy for the final equation. Ex. Use the given intermediate steps (1 and 2) for the production of one mole of tetraphosphorus decaoxide, to determine the ΔH for the overall reaction from its elements. Intermediate steps: (1) P4O6(s) 4 P(s) + 3 O2(g) ΔH = −1640 kJ (2) P4O6(s) + 2 O2(g) P4O10(s) ΔH = −1344 kJ The overall reaction is the sum of (1) and (2): (1) (2) P4O6(s) 4 P(s) + 3 O2(g) P4O10(s) P4O6(s) + 2 O2(g) P4O6(s) + P4O10(s) 4 P(s) + 3 O2(g) + P4O6(s) + 2 O2(g) Cancelling out species that appear on both sides of the reaction, we are left with the equation for the P4O10(s) overall reaction: 4 P(s) + 5 O2(g) The enthalpy of the overall reaction is the sum of the enthalpies of the intermediate steps. ΔH = (−1640 kJ) + (−1344 kJ) = −2984 kJ Since ΔH° < 0, the reaction is exothermic. Sometimes you may be required to reverse an intermediate step in order for the reactants and products you want to be on the appropriate side. If you reverse an intermediate step, don’t forget to reverse the sign of the ΔH. You may also need to multiply or divide the intermediate equations so that the quantities of reactants/products match the quantities you want in your final reactions. If you multiply of divide an intermediate step, remember to multiply or divide your heat value as well. Ex. The enthalpy changes for the following reactions are (1) 2 CO2(g) + H2O(l) C2H2(g) + 5/2 O2(g) ΔH = −1299 kJ (2) 6 CO2(g) + 3 H2O(l) C6H6(l) + 15/2 O2(g) ΔH = −3267 kJ Find ΔH° for the following reaction: 3 C2H2(g) C6H6(l) Is the reaction endothermic or exothermic? (1) 6 CO2(g) + 3 H2O(l) 3 C2H2(g) + 15/2 O2(g) ΔH = 3(−1299 kJ) (2) C6H6(l) + 15/2 O2(g) 6 CO2(g) + 3 H2O(l) ΔH = +3267 kJ 3C2H2(g) C6H6(l) ΔH = −630 kJ ΔH is negative so it is exothermic See Hess’s Law Assign 13 Enthalpy Change in a Reaction From Hess’s law, we now know the enthalpy change for a reaction can be determined by subtracting the sum of the heat of formation of the reactants from the sum of heat of formations of the products. ΔH°reaction = H f products − H f reactants Ex. Using the ΔH°f values from your tables, determine the enthalpy change for the combustion reaction of benzene, C6H6(l). 12 CO2(g) + 6 H2O(l) 2 C6H6(l) + 15 O2(g) ΔH° = H f products − H f reactants ΔH° = [12(−393.5) + 6(−285.8)] − [2(+49.0) + 15(0)] = −3267 kJ See Enthalpy Change in Rxn Assign Enthalpy and Phase Change: In all solids the particles vibrate back and forth weakly. They have low kinetic energy. Heating a solid results in greater vibration of particles so their kinetic energy increases. The solid particles move further away from one another, which causes their potential energy to increase. These energy changes can be observed by an increase in temperature and an increase in volume. o Note that the physical appearance of the solid will not change. The heat energy (Q) involved in a solid changing temperature can be calculated using mc∆t. A phase change occurs when the physical state of a substance changes. Melting, freezing, evaporation and condensation involve phase changes. Both melting and vaporization are endothermic processes: heat is absorbed from the surroundings. During the reverse processes, in which steam condenses or water freezes, heat energy is released to the surroundings. These are exothermic processes. These enthalpy values are negative. During a phase change, the temperature of the substance does not change even though you are adding/removing energy. This is because the energy being added or removed is working to change the state of the substance, not change the temperature. 14 The heat energy (Q) involved in changing the state of one mole of a substance at its boiling/melting point is known as the molar enthalpy of phase change. Molar enthalpies of phase change (kJ•mol−1) Substance ΔHvap ΔHcond ΔHmelt ΔHfre Water +40.7 -40.7 +6.02 -6.02 Methane +10.4 -10.4 +0.94 -0.94 Mercury +59.3 -59.3 +2.3 -2.3 Sodium chloride +207 -207 +27.2 -27.2 *Note: values for melting/freezing or vaporization/condensation are the same, but have opposite signs * When you have molar enthalpies of phase change you can use these values to calculate the heat energy. The formula is as follows: Q = ∆Hvap, cond, melt, fre ∙ n Where Q = heat energy ∆Hvap, cond, melt, fre = molar enthalpy of phase change n = # moles Ex. Calculate the enthalpy change involved when 17.2 g of liquid mercury is vaporized. First calculate moles of Hg: 1 𝑚𝑜𝑙 17.2𝑔 𝐻𝑔 × 200.6𝑔 = 0.0857 mol Hg ΔH = 0.0857 mol Hg(59.3 kJ/mol) = 5.08 kJ See Energy Needed to Melt Ice Lab & Enthalpy and Phase Changed Assignment Calorimetry The branch of thermochemistry concerned with measurement of such heat changes is known as calorimetry. Any device used for measuring a heat change is called a calorimeter. When we measure heat changes with this calorimeter, we assume that all the heat is absorbed by the water, and that the polystyrene cup does not absorb heat and that no heat is lost to the surroundings. If the quantity of heat emitted during the reaction is not large, such a “coffee cup” calorimeter will give reasonably accurate results. If large quantities of heat are involved, then heat losses to the surroundings will lead to inaccuracies. 15 Ex. A mass of 100 g of water is placed in a coffee cup calorimeter. The solution temperature is measured to be 14.4°C. A mass of 0.412 g of calcium metal is placed in the calorimeter. When the reaction is complete the temperature is recorded as 24.6°C. Calculate the standard molar enthalpy change for this reaction: Start by finding the heat amount that the water changed by (Q), then determine the amount of heat release by the reaction. Next we will determine molar enthalpy by dividing the heat that the reaction released by the the mole s of calcium used in the reaction. Ca(OH)2(s) + H2(g) Ca(s) + 2 H2O(l) Q = m c ∆t Heat absorbedwater = (4.18 J/g•C)(100 g)(10.2°C) = 4.26 × 103 J or 4.26 kJ Therefore, heat released by calcium= −4.26 kJ # of mol Ca= 0.412 g Ca(1 mol/40.08 g) = 0.0103 mol Ca Molar enthalpy = 4.26 kJ 0.0103mol = −414 kJ/mol The Flame Calorimeter: Some calorimeters may not be fully insulated. This means that the water in the calorimeter and the calorimeter itself both absorb heat. 16 Ex. A flame calorimeter composed of steel and with a mass of 322 g is filled with 225 g of water. The original temperature of the water and calorimeter is 10.6°C. When 1.02 g of ethanol, C2H5OH, is burned, the temperature rises to 38.4°C. Calculate the molar enthalpy of combustion of ethanol. Specific heat of steel = 0.44 J/g•C The heat released by the combustion process will be absorbed (mainly) by the water and the calorimeter as the temperature rises by 27.8°C (the change in temperature). Heat absorbed by weater and calorimeter: Q = mc∆t for water + mc∆t for steel Q = (225g)(4.18 J/goC)(27.8oC) + (322g)(0.44 J/goC)(27.8oC) = (+26100 J) + (+3900 J) = 30000 J Since 30,000 J is absorbed by the water and calorimeter, this means that 30,000J must have been released by the combustion of ethanol. Therefor Qcomb = - 30.0kJ # of moles of C2 H 5OH 1.02 g C2 H 5OH 1 mol C2 H 5OH 46.07 g C2 H 5OH 0.0221 mol C2 H 5OH molar enthalpy of combustion = 30000 J J kJ 1400000 or 1400 0.0221mol mol mol See Calorimetry Assignment . 17 18