In Sputnik's Shadow: American Scientists, Eisenhower, and the

advertisement

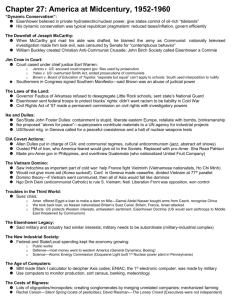

History of Modern American Science and Technology Session 4 American Science and Technology during the Cold War Jokes for Physicists “George W. Goes to Heaven” “Suitcase Bomb” “Ed’s Got a Bomb” “Less Edible Americans” “Top Twenty” “Garwin at the Guillotine” Main Arguments “Science in Policy” and “Policy for Science” Were Connected Rationale for Federal Support of Science Shifted during the Cold War American Science Advisers Most Valuable for Government due to Their Technological Skepticism The Goal of the President’s Science Advisory Committee Was to Control the Nuclear Arms Race and Promote Federal Support of Basic Research Technological Dissent Key to the Working of a Democratic Society Background on American Science Leaders of American Revolution, Newtonian Science, and Enlightenment Debate over the Role of Federal Government in Science John Quincy Adams’ “Lighthouse of the Sky” Technological Leap in Late 19th Century Scientific Buildup in Early Twentieth Century Coming of Age of American Science 1920s: Institutional Strength, the Quantum Generation, and the Coming of Refugees World War II: Radar, Proximity Fuse, Cryptology, and Atomic Bomb Dominance of Federal Government in American Science and Technology Americanization of International Science and Internationalization of American Scientific Community: e.g., T. D. Lee and C. N. Yang Impact of the Cold War on Science Policy Science Policy: “Science in Policy” and “Policy for Science” Dual Allegiance: Science or the Government? Science in Policy Scientists’ Movement The Nuclear Arms Race H-bomb Debate of 1950 The Oppenheimer Case of 1954 The TCP Study of 1954 Policy for Science ONR NSF Debate of 1950 AEC and High Energy Physics Who’s Using Whom? Shifting Rationales for Science Funding Bush Report of 1945: Assembly-line Model DuBridge-Rabi: Technological Evaluations PSAC: Technological Skepticism Sputnik: National Prestige 1960s: Education 1990s-present: American Competitiveness The Sputnik Shock Rhetoric of American Technological Superiority Psychological Impact of Sputnik 10/4/57 Opinion Leaders vs. Average Citizens White House Not Concerned Sputnik “Has Done US a Good Turn” Political and Public Pressure “Missile Gap” Ike, Sputnik, and PSAC Soviet launching of Sputnik, Oct. 4, 1957 Eisenhower meeting with the Science Advisory Committee of the Office of Defense Mobilization (ODM-SAC) in the Executive Office of the President, Oct. 15, 1957 Eisenhower announced James Killian, President of MIT, as science advisor, Nov. 7, 1957 White House announced the upgrading of the ODM-SAC as the President’s Science Advisory Committee Traditional Account Launching of Sputnik made Eisenhower realize the deficiency in the use of science in policy and led him to establish the PSAC system of presidential science advising. It was a natural and logical sequence of events that linked Sputnik with a reform in American science advising and science policy. A New Perspective Eisenhower’s response to Sputnik and establishment of the PSAC system of science advising were not pre-ordained, but shaped by a profound rethinking about nuclear war, a debate over science policy, and intense negotiations by rival scientists and politicians over the meaning of the Sputnik challenge. Eisenhower’s Rethinking on Nuclear War At a March 1957 meeting with ODM-SAC: “re-evaluating war as an instrument of policy, Had focused on “how to deter war—which has now become so destructive.” June 1957: “There will be no such thing as a victorious side in any global war of the future.” A Major Pre-Sputnik Debate on Science Policy Spring 1957, Eisenhower grew concerned over the rise of federal R&D, including basic research funding ODM-SAC scientists defended basic research Eisenhower agreed to protect basic research but DOD, in cutting R&D, went after basic research first Scientists, including ODM-SAC, demoralized Public Negotiation of Sputnik’s Meaning Rival scientists put different spins on Sputnik Edward Teller in media and Congress: Saw it as a military-technological threat “worse than Pearl Harbor” Called for a military-technological response: “We must win the H-war before It Starts!” “we must overcome the popular notion that nuclear weapons are more immoral than conventional weapons” “we must revamp our military planning to fight and win a limited nuclear war.” Werner von Braun also saw space as battle ground Moderate Scientists I.I. Rabi in a meeting with Eisenhower: Saw it as a challenge to American science and education: Soviets might overtake Americans in science just as Americans overtook the western Europeans a generation ago. Called for increased federal funding for science and education Test ban: Rabi: Despite Sputnik US had advantage and should enter into test ban with Soviets Teller: US needed to catch up; Soviets could always cheat Eisenhower Chose ODM-SAC’s Interpretation of Sputnik Nov. 7, 1957 Speech to Nation: Announced ODM-SAC member Killian as science advisor “My scientific friends told me”: We are ahead but could fall behind if we do not increase support for science education and basic research Nov. 14, 1957, 2nd “chin-up” Speech: “My scientific advisers place this problem [science education] above all other immediate tasks of producing missiles, of developing new techniques in the Armed Services.” Eisenhower Grew Critical of Teller July 1957: When asked about science advising, mentioned Waterman (NSF) and Bronk (NAS) as well as AEC and DOD scientists Pre-Sputnik (Summer 1957): Teller and Lawrence made it “look like a crime to ban [nuclear] tests.” “The scientists today in this field seemed to be running the Government rather than acting as servants for the Government.” Nov. 1957, Eisenhower complained about Teller's Pearl Harbor analogy: “Scientists have suddenly become military and political experts” and vice versa . Funding SLAC Project “M” Rhetoric Shifted from Scientists to Politicians National Prestige Republican Accelerator Politics of Big Science Zuoyue Wang, “Politics of Big Science in the Cold War,” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 25, pt. 2 (1995). Eisenhower, Sputnik, and PSAC Dec. 1960, Eisenhower to PSAC: “A deep sense of obligation.” “noted that more and more he has tended to put science advice into more and more subjects of national policy.” Why? Because they agreed on the meaning of Sputnik PSAC was valuable to Eisenhower as an independent voice of science speaking on not just the potentials but, even more importantly, the limits of technological solutions to social and political problems that became fashionable in the wake of Sputnik. Sputnik’s Shadow: Our own new age of technological enthusiasm Operation “Shock and Awe” We still need independent and expert voices of technological skepticism Eisenhower’s Thinking on Science, Defense, and Space First Concern over National Security Deterrence: Sufficiency, Not Excess Against Glamorous Space Projects No Enemy on the Moon Genuine Interest in Space Exploration and Basic Research Saw Danger of Intensified Inter-Service Rivalry Concerned with Garrison State, Big Government, and Momentum of Military Industrial Complex Eisenhower’s Legacy in Space and Public Policy Space Program Should Be Guided by “Reason, Fact and Logic” Priorities Should Go to Scientific Exploration and National Security but Not Propaganda Stunts Policy Makers Should Try to Understand the Scientific and Technical Aspects of Public Policy such as in Space Policy Makers Should Be Aware of Unwarranted Influence of Interested Parties in Pushing Space Program in One Direction or Another Public Understanding and Support Are Key to Successful Public Policy Foreign Policy Should Be Made on the Basis of Accurate Intelligence and Understanding of the Limit of Am. Power Scientists Represent an Important, Independent Voice in Public Policy, including Space and Defense Policy Post-Eisenhower Space Development Kennedy Launched Apollo against PSAC Advice American Scientists Ambivalent toward Apollo Excited about Landing but Misgiving about Illusion of Technological Fixes and Impact on Subsequent Direction of American Space Program JPL Mars Rovers Punctured Myth that Only Manin-Space Can Stir Public Interest After Apollo Decision, PSAC Scientists Helped to Ensure Its Success New Members also Supported Manned Space for Institutional Benefits PSAC and Environmental Policy Use of Pesticides (1963), Report that vindicated Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring Better science to control technological excess Public right to know Cautionary principle Dynamic process of regulation Wang, “Responding to Silent Spring,” Science Communication 19, no. 4 (Dec. 1997). Restoring the Quality of Our Environment (1965), warning of global warming “By the year 2000 there will be about 25% more carbon dioxide in our atmosphere than at present.” “This will modify the heat balance of the atmosphere to such an extent that marked changes in climate, not controllable through local or even national efforts, could occur.” Vietnam War Era Increasing Questioning of Priority of Manned Space Vietnam War Polarized American Society and Scientific Community PSAC Opposed Anti-Ballistic Missiles (ABM) and Supersonic Transport (SST) in late 1960s and early 1970s PSAC also Opposed Vietnam War as Misguided Use of American Technological-Military Power Nixon Abolished PSAC in 1973 Science Funding Declined during the Vietnam War Period Current Debate over Science, Defense, and Space Policy George W. Bush: No Science Advisor until after 9/11 Jack Marburg (physicist): “Invisible Science Advisor” (Bob Park, “What’s New,” 2/22/2008) Ambitious Human Return to the Moon and Landing on Mars in View of China’s and India’s Feats But Budget Cuts on Scientific Exploration of Space Political Benefits to Southern (Red?) States? Hilary Clinton: Reorient Space Program to Focus on Scientific Exploration and Environmental Problems on Earth Attacks on Scientific Integrity in Bush Administration: “Do You Support the President Politically?” Censorship over Global Warming Stem Cell Research Support for Intelligent Design Union of Concerned Scientists campaign for the integrity of science in the federal government: www.ucsusa.org We Still Need “Voice of Sense and Moderation” and Dissent of Independent Scientists in the White House—an Important Part of Eisenhower’s Legacy For Further Reading and Involvement Zuoyue Wang, In Sputnik’s Shadow: The President’s Science Advisory Committee and Cold War America and articles on website: www.csupomona.edu/~zywang Daniel Kevles, The Physicists Union of Concerned Scientists website (www.ucsusa.org) –sign petition on “Scientific Integrity” Robert Park of APS, “What’s New,” weekly email on science and politics and website: http://bobpark.physics.umd.edu/index.html