Reasoning about other people*s intentions

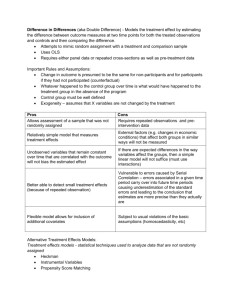

advertisement

Thinking: Emotion or Cognition? Ruth Byrne Professor of Cognitive Science rmbyrne@tcd.ie School of Psychology and Institute of Neuroscience, Lloyd Building Room 3.44 Thinking: Deciding, judging, reasoning, choosing Fast intuitive processes Emotion Slower deliberative processes Cognition Kahneman, 2011 Thinking, fast and slow Fast automatic, quick, little or no effort, no sense of voluntary control, innate skills we share with animals Slow effortful mental activities, requires allocation of attention, leads to subjective experience of agency, choice, concentration Danny Kahneman Thinking, fast and slow Fast …can detect simple relations, integrate information about one thing Slow …can follow rules, compare objects on multiple dimensions, make deliberate choices Thinking, fast and slow Dual processes ‘In two minds’ Evans, 2003 Steven Sloman Stanovich & West, 2000; Sloman, 1996 Keith Stanovich Outline Trust: Anger or assessment? Moral judgment: Passion or reason? Counterfactual thoughts: preparatory or affective? Ultimatum Game Two players must divide a sum of money The proposer specifies the division The responder has the option of accepting or rejecting the offer. If the offer is accepted, the sum is divided as proposed. If it is rejected, neither player receives anything Alan Sanfey Ultimatum game Suppose you’re the proposer. You have 10 euro to divide between you and anonymous B. B has the option of accepting or rejecting your offer. If B accepts your offer, the sum will be divided as you proposed. If B rejects your offer, neither of you will get anything. What amount would you offer B? Ultimatum game Suppose you’re B. Anonymous A offers you 1euro You have the option of accepting or rejecting A’s offer. If you accept A’s offer, the sum will be divided as A proposed. If you reject A’s offer, neither of you will get anything. Would you accept A’s offer? Game theory Nash equilibrium prediction If people are motivated purely by self-interest the proposer should offer the smallest nonzero amount. the responder should accept any offer Game theory? In fact, the modal offer is a 50/50 split Low offers of less than 20% of the total amount are rejected about half of the time Guth et al, 1982 Why don’t people accept ‘something for nothing’? Emotional decisions Low offers are often rejected after an angry reaction to an offer perceived as unfair Pillutla, & Murnighan, 1996 Unfair offers induce conflict between cognitive (“accept”) and emotional (“reject”) motives Sanfey et al, 2003 Humans and computers Shown pictures, told were of their partners 10 trials with 10 different partners 10 trials with computer Sanfey et al 2003 Ultimatum game Participants accepted all fair offers, with decreasing acceptance rates as the offers became less fair. Unfair offers of $2 and $1 made by human partners were rejected at a significantly higher rate than those offers made by a computer Sanfey et al 2003 Ultimatum game Two brain regions particularly active when participant confronted with an unfair offer anterior insula (emotional processing) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) (deliberative processing) Sanfey et al, 2006 Ultimatum game If insula (emotion) activation greater than dlPFC (cognitive) activation, tended to reject the unfair offer If dlPFC (cognitive) activation greater than insula (emotion) activation, tended to accept the offer. Neural evidence for a two-system account of decision-making Sanfey et al 2006 emotive cognitive Ultimatum game Transcranial magnetic stimulation disrupt processing in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex Van’t Wout et al, 2005 Outline Trust: Anger or assessment? Emotion first? Cognition overrides? Moral judgment: Passion or reason? Counterfactuals: affective or preparatory? Trolley (train) problem ‘You are at the wheel of a runaway train quickly approaching a fork in the tracks. On the tracks extending to the left is a group of five railway workmen. On the tracks extending to the right is a single railway workman. If you do nothing the train will proceed to the left, causing the deaths of the five workmen. The only way to avoid the deaths of these workmen is to hit a switch on your dashboard that will cause the train to proceed to the right, causing the death of the single workman. Would you hit the switch?’ Moral dilemmas Most people say they would hit the switch They decide to sacrifice the life of the single workman in order to save the five workmen Mikhail, 2009 Footbridge problem ‘You are on a footbridge over the railway tracks towards which a runaway train is quickly approaching. On the tracks beyond the footbridge is a group of five railway workmen. If you do nothing the train will proceed on the tracks, causing the deaths of the five workmen. The only way to avoid the deaths of these workmen is to push a nearby stranger off the bridge so that his large body will stop the train, causing the death of the stranger. Would you push the man?’ Footbridge problem Most people say they would not push the man Deontological reason Kant (1788/2002) People reason to moral judgments Deontological principle People follow a moral principle only if they would approve of it being universalised Immanuel Kant Passions “Morals excite passions, and produce or prevent actions. Reason itself is utterly impotent in this particular. The rules of morality, therefore, are not conclusions of our reason” Hume (1739-1740/2004) David Hume Moral intuitions ‘The emotional dog and its rational tail’ Haidt, 2001 Jonathan Haidt Emotions occur first? Abortion, child sexual abuse People have nearly instant implicit reactions to scenes or stories of moral violations Luo et al, 2006 Affective reactions are usually good predictors of moral judgments and behaviors Sanfey,et al, 2003 Dual processes A role for both reason and emotion as ‘dual processes’ Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001 Joshua Greene fMRI Footbridge-type but not train-type problems activate emotional areas of brain, detected in fMRI scans Greene et al, 2001 Greene et al, 2001 Brain impairment 6 patients with focal bilateral damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC) a brain region necessary for normal generation of emotions, social emotions Compared to Normal Controls and Brain Damaged Controls NB: Patients with VMPC lesions exhibit diminished emotional responsivity and reduced social emotions (e.g., compassion, shame, guilt) Koenigs et al, 2007 Abnormally ‘utilitarian’ pattern of judgments on personal moral dilemmas Normal in other moral dilemmas - Koenigs et al, 2007 But cognition does matter… Increased cognitive load interferes with judgments to e.g., hit the switch in impersonal dilemmas, take longer Greene, Morelli, Lowenberg, Nystrom & Cohen, 2008 Working memory Working memory capacity influences judgments on ‘personal’ and ‘impersonal’ dilemmas Moore, Clark & Kane, 2008 Separate systems of emotion and cognition… Monica Bucciarelli Are moral intuitions guided by separate evaluative and emotional processes, independent systems operating in parallel Sunny Khemlani Phil Johnson-Laird Bucciarelli, Khemlani & Johnson-Laird, 2008 Evidence Dilemmas Emotion questions and moral questions Emotion question: does it make you feel good or bad? Moral question- is it right or wrong? Faster response to emotion questions for ‘emotional-prevalent’ scenarios, faster to moral questions for ‘evaluation-prevalent’ scenarios Not always emotion first… Emotions sometimes precede evaluations and evaluations sometimes precede emotions, and so one is not always dependent on the other Bucciarelli et al, 2008 Outline Trust: Anger or assessment? Emotion first? Cognition overrides? Moral judgment: Passion or reason? Emotion and Cognition separate? Counterfactual thoughts: preparatory or affective? Outline Trust: Anger or assessment? Emotion first? Cognition overrides? Moral judgment: Passion or reason? Emotion and Cognition separate? Counterfactual thoughts: preparatory or affective? Alternatives to reality Common in entertainment Alternatives to reality Historical analyses ‘What if … Hitler had chosen to make his major attack …into Syria and the Lebanon? Would he have avoided defeat?’ Keegan, 1999; Tetlock & Lebow, 2001 Counterfactual Alternatives - Regularities People think ‘if only’ most often after bad events e.g., traumatic accidents, deaths, job losses, relationship break-ups but also sometimes after good events, ‘lucky chances’ E.g. winning a prize, meeting someone new, escaping a bad event Mandel et al 2005 People think ‘if only’ most often after unexpected events Markman et al 2010 David Mandel Functions of counterfactual thoughts Preparatory function If he’d been wearing a seatbelt he wouldn’t have been injured Neal Roese Learn from mistakes, work out causes, form intentions, plans, to avoid bad outcome in future responsibility, fault Key learning mechanism Epstude & Roese, 2008 Functions of counterfactual thoughts Affective function If he’d been wearing a seatbelt he wouldn’t have been injured Amplify emotions such as guilt, regret, remorse Roese & Olson, 1995 Neal Roese Functions of counterfactuals Amplify emotion Individual goes to a party, her friend’s boyfriend flirts with her and before leaving asks for her telephone number which she gives. Her friend is later very distressed. Niedenthal, Tangney & Gavanski, 1994 Functions of counterfactuals Amplify emotion Participants asked to imagine themselves as the individual and think ‘if only’ Directed to change Something about the individual’s actions Something about the individual’s personality Rated emotions they expect character to experience Functions of counterfactuals Amplify emotion Something about the character’s actions E.g., If only I hadn’t flirted with him GUILT Something about the character’s personality E.g., If only I wasn’t so disloyal SHAME Counterfactual imagination • People mentally simulate events • They create an alternative to reality by changing an aspect of their simulation • Emotions are ‘amplified’ Kahneman & Tversky, 1982 Amos Tversky Danny Kahneman What happens when you can’t create counterfactual alternatives? Counterfactuals and the Brain Brain injury Parkinson’s Schizophrenia Counterfactuals and the Brain Patient with damage to the DLPFC Exhibited perseveration and social impairments “a complete absence of counterfactual expressions” p.1367 Recently experienced various emotional stressors e.g., mother’s sudden death, career failure, typically associated with counterfactual thinking Knight & Grabowecky 1995 Counterfactuals and the Brain 18 patients with PFC lesions, 26 controls Beldarrain, GarciaMonco, Astigarraga, Gonzalez, & Grafman, 2005 Counterfactuals and the Brain Participants write down whatever was on their minds in response to 3 questions for 5 min: (a) recall a negative event in the past year, (b) what are you thinking about right now, (c) you just have completed a task for us. Record your reaction to it and any other thoughts about your performance on this task Record number of mentions of a counterfactual thought; grammatical markers, such as might have, could have, almost, if only, what if, if or wish that. Counterfactuals and the Brain Number of mentions of counterfactual thoughts Controls PFC patients Beldarrain,et al 2005 M=4 M=1 Counterfactuals and the Brain “This selective impairment in selfgenerated counterfactual thoughts should be considered and mentioned as part of the dysexecutive syndrome exhibited by patients with PFC lesions and cognitive rehabilitation programs should consider cueing counterfactual thoughts to help these patients reflect on their behaviors.” Beldarrain, Garcia-Monco, Astigarraga, Gonzalez, & Grafman, 2005, p. 276 Jordan Grafman Counterfactuals and the Brain Parkinson’s disease Prefrontal dysfunction in patients with advanced Parkinson’s 24 people with Parkinson’s, 15 controls Asked to recall a negative personal event; given three minutes to consider in detail; asked explicitly if they had any thoughts of how things might have gone differently, thoughts of ‘if only’s’ or ‘what if’s’. Controls M = 2.07 Parkinson’s patients M = 0.77 McNamara, Durso, Brown & Lynch, 2003 Counterfactuals and the Brain -Parkinson’s disease 1) Janet is attacked by a mugger only 10 feet from her house. Susan is attacked by a mugger a mile from her house. Who is more upset by the mugging? a) Janet (86% norms) b) Susan (0) c) Same/can’t tell (14%) Controls Parkinson’s patients McNamara, et al, 2003 M=2 M = 1.17 (chance level) Counterfactuals and the Brain -Parkinson’s disease “Counterfactual impairment may be one reason why these patients fail to learn from past mistakes and thus why they persist in maladaptive or dangerous behaviours… If patients suffer counterfactual impairment they are less likely to be able to handle social conversations fluently, to formulate plans easily, or to compare alternative outcomes imaginatively…” McNamara et al, 2003, p.1069 Patrick McNamara Counterfactuals and the Brain -Schizophrenia Frontal lobe deficits in some patients with schizophrenia (40%-50%) 14 schizophrenia patients, 12 controls Recall personally experienced negative events; recorded mention of counterfactual thoughts Controls Schizophrenia patients Hooker, Roese & Park 2000 M = 2.08 M=1 Counterfactuals and the Brain -Schizophrenia Counterfactual Inference Test Controls Schizophrenia patients Hooker, et al 2000 M = 2.33 M = 1.29 (chance level) Summary Trust: Anger or assessment? Emotion first? Cognition overrides? Moral judgment: Passion or reason? Emotion and Cognition separate? Counterfactual thoughts: preparatory or affective? Cognition first? Emotion arises from cognition? Emotion or cognition? Dual processes of fast and slow thinking Emotion is important aspect of ‘fast’ thinking Relationship of emotion and cognition is complex In some cases, emotion is immediate and cognition overrides it, e.g. trust In some cases, emotion and cognition appear to be separate systems – e.g., moral In some cases, cognition gives rise to emotion – e.g., counterfactual Reading Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Sanfey,A. et al (2003) The Neural Basis of Economic Decision-Making in the Ultimatum Game, Science 300, 1755-1758 Haidt, 2007, The new synthesis in moral psychology, Science 316, 998-1001. http://reasoningandimagination.wordpress.com/ https://mentalmodelsblog.wordpress.com/