REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL

advertisement

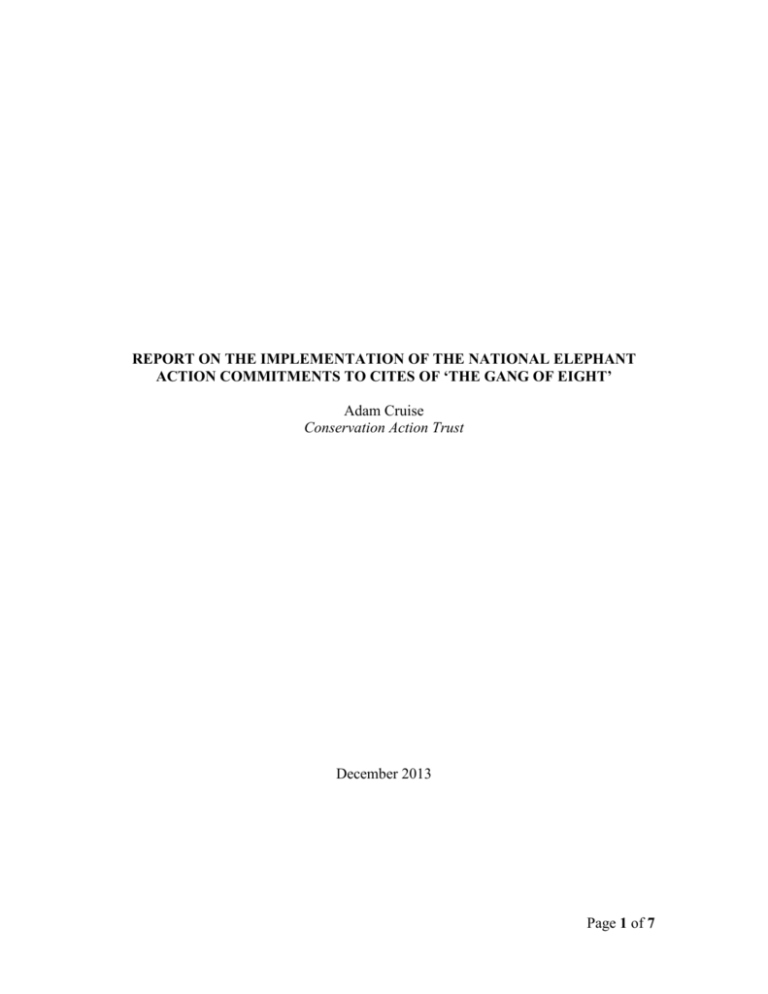

REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL ELEPHANT ACTION COMMITMENTS TO CITES OF ‘THE GANG OF EIGHT’ Adam Cruise Conservation Action Trust December 2013 Page 1 of 7 Introduction After a relatively stable period, the last three years have seen an unprecedented spate in the illegal trafficking of ivory. It has been argued the threat is so severe that unless urgent practical measures are taken, elephant populations, especially in West and Central Africa, will decline to the point of no return. Wildlife crime has developed into a multi-billion dollar industry and is, by some estimates, the fifth largest international criminal activity after narcotics, counterfeiting, illicit trafficking of humans and oil. As with narcotics, wildlife crime has become increasingly well organized and violent, posing a new level of threat to those responsible for managing and protecting wildlife. Problems are escalating fast, in terms of both the scale of poaching and the audacity with which poachers take high value species like elephants. Mass killings of elephants in individual protected areas have now occurred in several African countries, while crime syndicates operate with seeming impunity across many Asian countries where the demand for ivory is greatest. Preamble In March this year, the twenty-member Standing Committee of CITES, at its 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP16), singled out 8 countries most heavily implicated in the large-scale illegal ivory trade. Vilified by the media as The Gang of Eight, three of the countries are African, the African Elephant range states, which are the knot of countries that make up the bulk of the East African sub-continent where ivory is sourced: Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Three are considered transit states, the gateway nations for the trafficking of ivory: Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines. The last two are referred as ivory destination countries where demand for the product is greatest: China and Thailand. The Standing Committee then put forward a motion stating that unless each of the offending countries submit a detailed national elephant action plan to curb the illegal trade of African elephant ivory by May 15th 2013, a ban on all legitimate wildlife trade on each nation would be enforced. Such a ban could have significant consequences on these countries as they rely heavily on the economic benefits of such trade. The trade in orchids and crocodile skins in Thailand and China is apparently big business, big enough to take the Standing Committee’s threat seriously. The CITES body have also demonstrated that they mean business. The stringent no-trade measure has already been enforced on Somalia, Afghanistan, Lesotho and Mauritania, while during the conference the West African nation of Guinea was slapped with the ‘All Trade’ ban for its persistent violation in the trade of great apes. In lieu of a possible ban, all eight countries, according to the Standing Committee report made directly after CoP16, immediately ‘demonstrated a strong commitment to take immediate, decisive actions in combating the illegal trade in elephant ivory, and collaborating with the Standing Committee and the CITES Secretariat in developing and implementing national ivory action plans’. The Secretariat, in collaboration with CITES Page 2 of 7 sub-bodies, MIKE and ETIS, laid out the timeline and framework parameters for all eight national plans to adhere to. The guidelines that each national elephant action plan had to adhere to were: - - to include legislation and regulation that must be imposed and enforced both at a national and international level, the latter to have measures in place for collaboration with other countries and programs of outreach and public awareness to be widely disseminated and effectuated among government bodies, traders and consumers. The plans were to be urgently implemented, to begin no later than July 2013 with a deadline for full implementation the following July when the Standing Committee met for their annual sitting for the 65th time since inception (SC65). During the course of the next 12 months each country was to continually report to the Secretariat on the development and progress of each of their plans. At face value, it appeared the Standing Committee meant business, but the big question since March is whether the Gang of Eight, despite paying lip-service to a full commitment of the CITES demands, have actually submitted any plans. If so, have they followed the framework dictated by CITES? Also, now that we are halfway through the 12-month period, have the plans been implemented, or have the governments of these nations simply green-washed the whole affair with a basic draft in order to maintain a stay of execution? Nothing to date has been officially publicised, either from CITES or the eight offending nations but with a little scratching I can report that all eight have timeously submitted their drafts (I know this because all eight plans have somehow, as they say in some parts of Africa, fallen on my head). The submitting of the eight plans are, at least, a step in the right direction but what immediately struck me when I glanced over them was the lack of in-depth detail in all of them. I understand these were mere drafts but each country, it seems, submitted a plan according to the bare minimum set out by the CITES framework, just enough to prove compliance. For all eight drafts there are a mere 50 pages in total, including title and cover letters. Vietnam’s entire draft was printed on a single page. Thailand’s was the most detailed with eleven. Report on plans by ‘Gang of 8’ What follows is an outline and comment of each country’s draft. CHINA China have actually submitted two plans – one for mainland China and the other for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, perhaps because HKSAR is somewhat different in the ivory saga than the mainland. As the main gateway of ivory into China, HKSAR could be considered both as a transit and a destination. Page 3 of 7 Mainland China’s plan is concerned primarily with making clear distinctions between the legal and illegal trade in ivory. In short, they don’t see a problem with killing elephants, as long as it’s ‘legal’. The plan consists of implementing an improved certification card system for traders, which would be revoked for non-compliance. There is no mention of a prosecution process for illegal trade. The certification card system is to be in place by the end of 2013. Also they have committed to ‘organise at least one [just one?] targeted operation on illegal trade in ivory each year’ for both manufacturers and retailers, and there is to be an undertaking to make consumers aware of the difference between buying legal versus illegal ivory. Other than a further undertaking to improve policing and co-operation with other nations and some financial assistance with policing and investigation in the African range states, as per the set parameters, this is the sum total of mainland China’s game plan. Hong Kong, being a gateway port, concentrates more on illegal shipments and influx at point of entry. Improved custom control is very much part of the HKSAR plan but again it is thin on detail other than a broad commitment to improve technology in detection of shipments, like container x-ray machines and DNA forensic analysis on seized products. They have also agreed to work closely with CITES, INTERPOL and other nations with intelligence exchange. It was interesting to read in the cover letter of the HKSAR’ s Director of Fisheries, Agriculture and Conservation, Patrick Lai, who made a point of reminding John Scanlon, the CITES Secretary-General, of a joint CITES/HKSAR inspection conducted in January and February 2013 of 100 art and craft and antique shops that sell ivory. Amazingly, all 100 shops were found compliant and each possessed a valid license to trade in ivory, a barely belivelable outcome given that Hong Kong sees more illegal movement and trade in illegal ivory than any other region. Nonetheless, it was a gentle reminder from HKSAR that they did not necessarily have to add much to their action plans other than to improve point-of-entry surveillance. Hong Kong, at least as a consumer or destination market, is, according to Lai, already compliant with CITES regulations. THAILAND Thailand’s plan although the longest of the eight drafts is less detailed than both China and HKSAR. Five of those pages are dedicated first to remind the Secretary-General that Thailand was one of the original signatories of CITES when it was formed in 1973 and therefore one of the important forerunners in management and regulation in the trade in ivory. Second, there is a wafty undertaking to revise the current law on the use domestic elephants as draft animals in Thailand, notwithstanding that it is the illegal trade in African Elephants that are in question, not Asian elephants. Thailand, in the African Elephant context, is a destination country, not a range state, so their plan is incongruous to the framework laid out by CITES. Thailand does briefly admit in the draft that there are no provisions controlling the possession of African Elephant ivory in Thailand. They have pledged to revise the current legislation, especially by marking stockpiles and setting up a system to distinguish between illegal African and legal Asian ivory, but for the statute to be revised it first has to pass Page 4 of 7 cabinet for approval and then both the House of Representatives and Senate before a draft revision can be enacted into law – a process, they reckon, that would take 4 years and six months. This excludes the subsequent monitoring and policing of the revised law, so it could take more than a decade before favourable results are shown. Thailand has, however, committed to a public relations campaign discouraging consumers and tourists from buying ivory. Although, again, it has to pass through the lengthy governmental process before it is enacted. KENYA Kenya, as a range state, has different problems to the destination countries. Firstly, they have to deal with the increasingly militaristic proclivity of the poachers as well as trying to seal their ever-porous points of exit, particular at the port of Mombasa. As with the other two range states cited, Kenya furthermore lacks the necessary wherewithal and funding to deal with such issues. Which is why CITES, and China, have pledged financial aid in assisting with combatting illicit trade crime in Kenya. Nevertheless, Kenya cannot simply plead poverty and wash their hands of the issue. Good governance is at the heart of the matter. At present Kenyan prosecution policies are woefully lenient. An offender caught smuggling ivory recently was fined just a dollar. Accordingly Kenya have been instructed to get tougher on offenders, which they have promised to do in their action plan, but again this requires government approval and may take time to implement. The security of ivory stockpiles is also under scrutiny and Kenya have endeavoured to better mark and audit stockpiles and introduce a DNA-controlled database. Cross border raids in co-operation with Tanzania and Uganda are also on the cards with a promise of continued reporting on progress to CITES but thus far no concrete results have been produced. UGANDA Uganda, like Kenya, promises to get tougher on offenders. They have also promised a complete revision of their National Wildlife Act ‘to address gaps in the legislation’. In the meantime, they would employ more wildlife authorities at exit/entry points, especially at the borders with the DRC and South Sudan. They have, however, stated that in order to create effective public and governmental awareness campaigns, solicitation of outside funding is paramount. In a nation where donor funding is notoriously mismanaged, such an inclusion in the action plan is suspect at best. As with many of the other eight, the Ugandan Elephant Action Plan appears to paying lip-service to the basic framework requirements set out by the Standing Committee. TANZANIA The Tanzanian plan was flippantly submitted to the Secretariat by Herman Keraryo, the Director of Wildlife, with the rider that since Tanzania ‘is still planning to submit its elephant down-listing proposal at CoP17 in 2016, we request the Secretariat to provide us with technical and financial assistance.’ In other words, ‘we don’t really agree about having to submit a plan since we already propose to down-list elephants but since we are forced to provide one, we require money to do so’. The actual plan reflects this desire as it Page 5 of 7 demands 4-wheel drive vehicles, a helicopter, guns, ammunition, more game scouts to be recruited and trained, inspection facilities and equipment installed and more wildlife areas demarcated before any ‘action’ can take place. There is also the usual promise of marking and auditing stockpiles and tougher prosecution on offenders. Like China with HKSAR, Tanzania has a separate plan for Zanzibar, which they regard as the primary offending port for the exit of ivory contraband. PHILIPPINES As with Tanzania, the Philippines were expressive in their demand for financial assistance and even gave a figure of US$30,000 for the training of ivory identification and marking systems for law enforcement officers. But the Philippines, at least, seem serious about committing to their national action plan. This is demonstrated by the subsequent crushing of their ivory stockpiles on 21st June 2013, a first for a country outside Africa. At least, we the public know they have begun to implement their plan. They are also the only country of the eight to show positive results with their implementation. As part of their plan, the Philippines undertook to form a governmental investigative operations group on ivory (POGI), which was in operation by June and the body has already had some notable successes against ivory smugglers. The Philippines appears to be the only country of the Gang of Eight to commit whole-heartedly to their national elephant action plans, a trend noticeable with their much-publicised desire to eradicate all illegal wildlife trade within their borders. MALAYSIA As one of the main transit countries in illegal ivory Malaysia has come under particular scrutiny. Like the Philippines they have wasted no time in implementing their plans which were to revise current legislation in accordance with CITES’ demands. In particular, the increase of administrative power of customs officials and port authorities to inspect, seize and hold ivory shipments. These proposals have all been gazetted so far. Malaysia claim they will be conducting 20 raids or random checks on all points of entry and exit throughout the nation within the 12 month timeframe as well as cross-border collaboration with Thailand. However, the effectiveness of the Malaysian authorities remains dubious. Just last month two separate shipments weighting a combined three tons of illegal ivory were seized in Hong Kong and Vietnam respectively. Both had passed through Malaysian ports in crates labelled as seashells. Malaysia thus continues to remain the worst offender of the three transit states. VIETNAM Like Hong Kong, Vietnam is a primary entry point of illegal ivory into China. As a result their plans have consisted mainly of securing their northern border, as well as the points of entry, particularly the port cities of which, like Malaysia, there are many. As we have seen, Vietnam recently seized two tons of ivory that had passed through Malaysia at their Page 6 of 7 northern port city of Hai Phong. So it appears, despite their sketchy draft plan, the implementation thereof is working. Yet, the biggest hurdle for Vietnam is widespread corruption, particularly among senior officials and although noises about addressing these issues have been made, this issue remains an almost insurmountable challenge. Conclusion To conclude, my preliminary findings on the implementation and success of the various elephant action plans at midpoint of the timeframe issued by CITES are sketchy at best as many of the countries as well as CITES are officially keeping mum on information garnered. Having said that, we, the concerned citizens, can make educated guesses based on secondary information. Reports of rampant poaching continues unabated throughout Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania but trends are indicating that poachers are now targeting other African countries, as witnessed with the case of the mass elephant slaughter in CAR in April this year and poisonings in Zimbabwe in August/September. Perhaps this is as a result of tougher measures within the three East African nations? Ivory smugglers no longer seem to prefer Mombasa or Zanzibar as an exit point and are increasingly making use of Mozambique and a variety West African ports to smuggle ivory. Malaysia remains a major problem as a transit country with authorities being unable or unwilling to halt or reduce the amount of illegal ivory getting through. Vietnam and Hong Kong have both made an effort with some success, but while we know of some stocks seized, we will never know how many shipments get through undetected, so its impossible to gauge the real success of their action plans. The Philippines is the shining example within the Gang of Eight. They have not only demonstrated a public readiness but a strong commitment to halting the trade in ivory. The crushing of their stockpiles sent a clear message in that regard. Thailand have muddied the issue with an inclusion of their domestic elephant population, and anyhow their legal system seems to be mired in red-tape, so I doubt we will be seeing positive results from them soon, if at all. China, as the major consumer country, on the other hand, is the true bogie of the group. Their insistence on keeping ivory as a consumer product will continue to fuel the trade in illegal ivory and unless they commit 100% to the complete halt of ivory sales, elephants will continually get slaughtered throughout Africa. Page 7 of 7