Federalists v. Anti-Federalists

advertisement

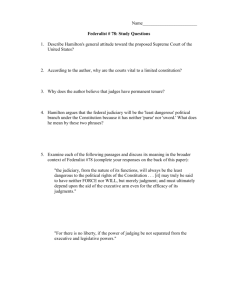

Federalists v. Anti-Federalists On Whether We Needed a Bill of Rights Bill of Rights Institute August 06, 2007 Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University The Debate Over the U.S. Constitution During the period of debate over the ratification of the Constitution, numerous independent local speeches and articles were published in newspapers all across the country. The articles in favor of the Constitution were written under the pseudonym “Publius.” The authors were Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. They were not only drafted as propaganda for ratification but also to influence the interpretation of the Constitution, which as a compromise document, had many provisions which could be interpreted in different ways. The essays were collected by publishers right from the beginning and published together in various forms. As such, they became an important tool for judges and other political actors in interpreting the Constitution. Initially, many of the articles in opposition to the Constitution were written under pseudonyms, such as “Cato,” “Brutus,” “Centinel,” and “Federal Farmer”— actually George Clinton, Robert Yates, Samuel Bryan, Melancton Smith, and Richard Henry Lee among others. Eventually, famous revolutionary figures such as Patrick Henry came out publicly against the Constitution. Unlike the authors of the Federalist Papers who worked together, the Anti-Federalist papers were not a coordinated effort. Scholars later published the best and most influential of these articles and speeches into a collection which came to be known as the Anti-Federalist Papers. Who Were the Federalists? Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) was the primary intellectual force for nationalism throughout the founding period, was Washington’s most trusted advisor, and the principle architect of the nation’s economic policy as Secretary of the Treasury. James Madison (I) (1751-1836) was aligned with Hamilton and the Federalists early on and was the principle architect of the Constitution. As a member of the House of Representatives, he drafted the Bill of Rights and introduced it in the first Congress. Both Hamilton and Madison wrote most of the Federalist papers. John Jay only wrote a few as he was ill and unable to participate more fully. The Federalists’ Argument In Federalist No. 84, Hamilton argued: It has been several times truly remarked, that bills of rights are in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgments of prerogative in favor of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. Such was Magna Carta, obtained by the Barons, sword in hand, from king John...It is evident, therefore, that according to their primitive signification, they have no application to constitutions professedly founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate representatives and servants. Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing, and as they retain every thing, they have no need of particular reservations. "We the people of the United States, to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the United States of America." Here is a better recognition of popular rights than volumes of those aphorisms which make the principal figure in several of our state bills of rights, and which would sound much better in a treatise of ethics than in a constitution of government.... I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and in the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers which are not granted; and on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why for instance, should it be said, that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power. Who Were the Anti-Federalists? George Mason (1725-1792) wrote the Virginia Declaration of Rights, detailing specific rights of citizens, which became the model for the Declaration of Independence and the first ten Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Patrick Henry (1736-1799) was a prominent figure in the Revolution, known for his "Give me liberty or give me death" speech, Governor of Virginian and a radical rights advocate. The Anti-Federalist Argument At the Virginia Ratification Convention, Patrick Henry spoke: If you give up these powers, without a bill of rights, you will exhibit the most absurd thing to mankind that ever the world saw — government that has abandoned all its powers — the powers of direct taxation, the sword, and the purse. You have disposed of them to Congress, without a bill of rights — without check, limitation, or control. And still you have checks and guards; still you keep barriers — pointed where? Pointed against your weakened, prostrated, enervated state government! You have a bill of rights to defend you against the state government, which is bereaved of all power, and yet you have none against Congress, though in full and exclusive possession of all power! You arm yourselves against the weak and defenseless, and expose yourselves naked to the armed and powerful. Is not this a conduct of unexampled absurdity? What barriers have you to oppose to this most strong, energetic government? To that government you have nothing to oppose. All your defense is given up. This is a real, actual defect. It must strike the mind of every gentleman. Article 7: 10 of 13 States Needed for Ratification Compromise: Ratification and a Bill of Rights Overall, the Federalists were more organized in their efforts and ultimately succeeded – but not before compromising with the Anti-Federalists on the issue of a Bill of Rights. Five states ratified the Constitution quickly and relatively easily: Delaware (300), Pennsylvania (46-23), New Jersey (38-0), Georgia (26-0), and Connecticut (128-40). Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia remained and would be crucial in terms of population stature for the new government to succeed. Debates in Massachusetts were very heated, with impassioned speeches from those on both sides of the issue. Massachusetts was finally won, 187-168, but only after assurances to opponents that the Constitution could have a bill of rights added to it. Subsequently, Maryland (63-11) and South Carolina (149-73) agreed and New Hampshire (57-47) cast the deciding vote to reach the required nine states. The votes in Virginia (89-79) and New York (30-27) were hard-won, and close. Confidence was now high that the new government would succeed. Making good on their promise, a number of amendments were passed by Congress, allying the fears of the holdout states. North Carolina (194-77) and finally Rhode Island (34-32) relented and ratified well over a year after the Constitution took effect. Following the passage of the Constitution and what became known as the Bill of Rights, the divisions between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists coalesced around the issue of federalism— specifically the aggressive fiscal policies of Federalist Alexander Hamilton. Federalists favored broad construction of the Constitution and strong national powers. George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and John Marshall were proponents of this general philosophy. Anti-Federalists favored strict-construction of the Constitution and advocated popular (State’s) rights against what they saw as aristocratic, centralizing tendencies of their opponents. Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party formed around these beliefs and included James Madison (II), James Monroe who both succeeded Jefferson as President during “The Virginia Dynasty” (1801-25). In one form or another, these two competing philosophies have dominated American politics throughout its 200-year history from the Civil War to regulating the economy during the New Deal to current debates over abortion. The Two-Party System Further Reading The Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers have been collected in numerous forms including cheap paperback versions and now on-line for free. Some Secondary Sources: – Amar, Akhil Reed. 2005. America's Constitution: A Biography. New York: Random House. – Chernow, Ron. 2004. Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin Books. – Storing, Herbert J. 1981. What the Anti-Federalists Were For: The Political Thought of the Opponents of the Constitution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.