Inequality in Australia

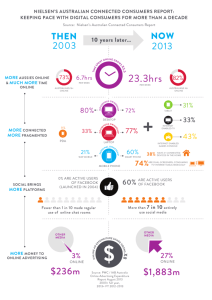

advertisement

The John Button Oration, August 2015, Melbourne Writers’ Festival Thank you so much. It’s a real thrill to be here at the Melbourne Writer’s Festival, my first invitation and hopefully not my last. I want to start by (also) acknowledging the traditional owners of the land, past, present and future generations of the Kulin Nation. The recognition of Indigenous peoples at the beginning of public lectures like this one is now, happily, de rigueur. Perhaps it has paved the way for broad public support for recognition of prior occupation in our constitution, which will hopefully occur sooner rather than later. (Recent polling shows broad support at about 63%) My only quibble with the ‘welcome to country’ is that it is often done too quickly and the opportunity it provides to inform the audience about the ancient history of the land we stand on is often missed. Sometimes a speaker acknowledges Indigenous generations and the cultures they have miraculously managed to maintain and then moves on to speak about their chosen topic, without thinking of making connections between this topic and the challenges and opportunities facing indigenous peoples. You can’t speak about inequality in this country, as is the chosen theme of my lecture tonight, without talking about Indigenous Australians, and I will do so later in my talk. In preparation for tonight, I did some cursory research on the Kulin Nation. It is made up of five distinct but related language groups, who formed a relatively harmonious confederacy, one that worked well together, traded and intermarried. One of the more interesting bits of information I learned in my research about the Kulin Nation is that the word ‘Kulin’ itself comes from the tribes’ common word for ‘a human being’. In a spectacular but not unique example of unequal treatment John Batman attempted the only recorded treaty with the Kulin people, claiming to exchange blankets and other goods for almost 250,000 hectares of land in the Port Phillip District. This treaty was not recognised by colonial authorities. Addressing inequality in all its forms was a lifelong quest of the man after whom this oration is named, John Button. I had the chance to meet John only once. I was about 25 years old, attending a Fabian Conference at Melbourne’s Trades Hall. The Labor Party was in the middle of its long period of opposition and Labor figures were busy publishing books about The Third Way and wondering whether this internet thingy would prove important in the years to come. At the pub afterwards I was sitting with a few other participants and John interrupted our discussion to praise our speeches but also to gently admonish us about a glaring omission in most of the talks the day. “Don’t forget about poverty”, he told us. And off he went with a wink and a smile, briefcase in hand and a jaunty scarf around his neck. In addition to honouring John’s legacy, I also want to acknowledge members of his family who are here tonight. As the daughter of a ‘great man’ stroke ‘workaholic’ I recognise it’s not all fun and games to be the support team for a public figure. It’s just terrific that you continue to ensure The John Button Foundation thrives and can host events like this. There is one more person I want to recognise tonight. Joan Kirner. As you would all no doubt be aware, Joan died earlier this year. Lucky me, I considered her a friend and mentor. And I would like to acknowledge Ron Kirner, who is here tonight. My thoughts this evening are dedicated to Joan and inspired by her example, a life led fighting for fairness. I learned many important lessons from Joan. She taught me a lot about power, how to use it, get it and keep it. But she also taught me power is only important if it is exercised to help those who don’t have it. For Joan it wasn’t about how high you could climb but if you could pull people up with you. And make the climb easier for those coming after. Tonight I’ve promised to give you all a glimpse into the mind and mood of Australians when it comes to issues of inequality and fairness. I should stress that I am not an expert on social and economic inequality in itself. I am an expert on perception rather than reality, which is exactly why people like me shouldn’t be given too much of a say in policy matters or in politics for that matter. I do however, have a very general understanding of the current nature of inequality in Australia through my involvement in the Chifley Research Centre’s Inclusive Prosperity Commission. The Commission released its first in a series of discussion papers a few weeks ago, warning of a new level of inequality emerging in Australia. That report shows that while Australia is one of the few countries to have resisted the trend to a shrinking middle class up until now, there are new threats on the horizon. Income inequality in Australia has been rising and we are now in the bottom half of the equality ladder. Those at the top, our most wealthy Australians, have been taking a greater share of the nation’s income. This isn’t as bad as in the United States but it is getting worse. The gender pay gap is widening and it wasn’t that flash to start with. Wealth inequality, especially driven by housing, is far worse than income inequality. There are huge and obvious implications here for younger generations. In addition to this, wages have failed to keep pace with productivity improvements. There is a long list of social groups that face large and different challenges in terms of workforce participation, wages and wealth and access to infrastructure of all kinds. These groups include Indigenous Australians, frail and those caring for frail Australians, people and those caring for people living with disabilities and those living in poorly serviced regional, outer urban and rural areas. And of course those almost totally forgotten Australians, those living in homes where there is multigenerational unemployment. That’s a very cursory description of the reality for you. Now let’s talk ‘perception’. After ten years of researching Australian attitudes, it’s clear that a long period of affluence – what journalist George Megalogenis’ calls ‘the longest decade’ – has ramped up the lifestyle expectations of some parts of the Australian population. Your perceptions about what it is to be ‘middle class’ or ‘doing well’, your values and the extent you are prepared to use debt to fund particular lifestyle choices (such as yearly overseas holidays or private schooling) directly impact on any perceptions you might have about fairness, whether you are getting ‘a fair go’ or whether other people are. It also shapes your sense of optimism or pessimism about the role of government and the direction of economy. Here’s a telling example of this. My previous employer, Ipsos, runs a large and robust study on consumer trends and sentiment as well as media use. It’s called Enhanced Media Metrics Australia or, the friendlier, Jane Austenish title of emma. The emma project surveys over 54,000 Australians a year. It collects a huge amount of data about their attitudes and behaviours from everything from shopping to immigration. Out of this data, Ipsos created what we in the research biz call a segmentation, a classification of the entire population into groups or types. There are ten in all. There are two segments in this study, which, when compared, show exactly how much expectations of what it is to be ‘middle class’ shape perceptions of inequality and fairness. These segments – we call the first group Assertive Materialists and the second Conscientious Consumption – are on the face of it very similar. Both groups are dominated by middle and upper middle class families living in urban areas, with children parented by highly educated, big earners who are strongly engaged with new technology (particularly smartphones and tablets) and social media. What divides these two groups are their values and attitudes to what it means to be ‘middle class’. The Assertive Materialists (11% of the population) place great value on social mobility, status and lifestyle. Private schooling, for example, is a priority for members of this group. They are almost entirely internally focused. They are also heavily committed in terms of mortgage and credit card debt and spend a lot on discretionary items. They are pessimistic about the role of government, worried about the direction of economy and their own financial future. In focus groups they are likely to talk about high taxes, cost of living and ‘doing it tough’. They are less likely to believe the government should intervene on issues like climate change or have a more expansive immigration program. In contrast, the Conscientious Consumption group (9% of the population) while in a very similar situation economically to their Assertive Materialist neighbours, see the world quite differently. They are more optimistic about their own economic future and the country’s, more confident about sending their kids to a public school, supportive of the idea that government should do more in the area of climate change and open to an increase in immigration. For some members of the Australian middle class, ‘doing it tough’ has almost nothing to do with how the economy is or the reality of their own economic situation. It has to do with anxiety and expectations of what it is to be ‘middle class’. Let’s return to my brief description of the current state of economic and social inequality outlined by The Inclusive Prosperity Commission. To what extent do Australian’s perceptions of inequality and fairness mesh with that reality? I’m pleased to tell you that in my experience, perception and reality aren’t entirely at odds. In fact there are some heartening continuities. When I was director of the long running Mind & Mood Report, I conducted countless studies where discussion group participants discussed the notion of inequality, either directly or indirectly. These insights from the last 10 years of Mind & Mood studies have been usefully summarised in a recent report, co-funded by ACOSS, The Reichstein Foundation and The Australian Communities Foundation. In the forward to that report, ACOSS CEO Cassandra Goldie quotes statistics from her own organisation’s analysis of inequality in Australia, which meshes with much of what is in the Inclusive Prosperity report when it comes to rising income and wealth inequality. She writes … A person in the highest 20% of income earners has around five times as much income as someone in the lowest 20% of income groups. Wealth is far more unequally distributed than income. A person in the highest 20% of income earners has around 70 times more wealth than a person in the lowest 20% of income earners. The average wealth of a person in the highest 20% increased by 28% over the past eight years, while for the lowest 20% it increased by only 3%. Meanwhile, the lowest 40% of households own just 5% of all wealth. And for those who think it’s all relative, [ACOSS’s] research shows that inequality in Australia is higher than the OECD average. These facts are indeed ‘felt’ by the Australian population. Except for a concern about rising cost of living (in general the cost of living has stabilised or even decreased slightly for most Australians over the last 10 years), Australians are worried about the casualisation of the labour market, job insecurity (not just for themselves but for other Australians, particular younger ones), wage restraint, the high cost of housing and its impact of wealth inequality and the high price of entry into the property market. In addition, while poverty is not as popular a topic as supermarket prices in the discussion groups I’ve conducted over the years, there is in general an appreciation that there are fellow Australians who are living in poverty or part of the working poor. Indeed, it seems that some are becoming more conscious of the number of people who are slipping into ‘real’ poverty and associated problems such as homelessness - with little hope of being able to find a way out. The public response to the 2014 federal budget was a beautiful example of the still existing altruistic impulse in the Australian populous, evidence we are still wedded to fairness not just as an abstract concept but as a concrete outcome. That budget seemed to trigger a fresh wave of sympathy towards those who were genuinely ‘doing it tough’. According to quantitative research conducted by Ipsos in the immediate aftermath of that budget, 70% of respondents to a national representative survey of over 1000 voters believed the burden of the budget would not be shared equally across society. They thought the budget was unfair and worried about its impact, not just for themselves, but on other people. Qualitative research conducted seven weeks down the line also suggested that participants were worried that the budget was taking too much away from the young, the older and the more vulnerable in our society. Another question worth asking is … do Australians even feel as if the notion of egalitarianism, encapsulated in the Australian vernacular phrase of ‘the fair go’, is even relevant anymore? The idea of an egalitarian society and the right to ‘a fair go’ is one that Australians still hold dear. The values of fairness and equality are often seen as being at the heart of what it means to be Australian. In a report the Mind & Mood team did in 2011 on Australian identity, there was plenty of evidence that Australians across divisions of class, gender and generation still believed that Australia was and should fight to remain an egalitarian society. We give everyone a fair go. We have a fair go attitude. The thing about Australia that is a good thing is that everyone should get a fair go. Fair go, mateship, helping each other. … It is a strong Australian value. These are just some of the typical comments from the participants in that study. And yet this largely positive picture, the continuity between the reality and the perception of inequality and the remaining support for the concept of ‘a fair go’, is shot through with dark and unsettling strains of prejudice and fatalism. By fatalism I mean the sense Australians have that while inequality is rising and that it is, to use that hackneyed phrase, ‘unAustralian’, there isn’t much that can be done about it. In addition, it may be that we are losing some of our sense of the damage (both social and economic) that inequality can cause. In the quantitative research done by Ipsos after the 2014 budget, while a strong majority of respondents, 73%, thought the gap between rich and poor is getting wider, only just above half of those same respondents, 58%, believed having large differences in income and wealth was bad for society. In addition only 67% of those surveyed thought that rich people don’t pay their fair share of tax. I guess that was a survey with a 23% quota of people who consider themselves to be rich! In terms of prejudice we know that Australians’ commitment to a fair go and mateship may not extend to people who arrive here on boats to seek asylum. Whoever came up with the idea of describing these people as ‘queue jumpers’ was pretty clever, in a Dr Evil cat-stroking type way. The phrase manages to tap into Australians’ ideas of ‘fairness’, at the same time using that phrase to attack those who have been treated unfairly. Who amongst us hasn’t been enraged when someone cuts into line at the polling booth or coffee cart? Australians love many things, an orderly queue is one of them. Paranoia about what is now commonly called ‘illegal immigration’ or ‘illegal arrivals’ is now rampant in the community. And it is paranoia. Globally Ipsos released a 14-country study in August last year called ‘The Perils of Perception’. The Australian wave of research included a survey of 1000 voting aged Australians. The report found that Australians significantly overestimated the numbers of migrants in this country. They guessed that the percentage of the population who were first generation migrants was on average 35%; it is in fact 28%. More worrisome was that 33% of those surveyed though it was 56%, more than double the actual figure. Why? 42% of those surveyed believed it was because “people come into the country illegally so aren’t counted”. The same number also agreed with the statement “I still think the proportion is much higher”. So even in the face of clear facts about numbers of migrants, Australians are convinced that our population is bloated with illegal arrivals. Such is the almost perverse desire, unchecked by so much media and political discussion, that we are being overrun by people from overseas. Furthermore in terms of prejudice, the story of a fair and equal Australia is only occasionally disrupted by the question of the status and future of Indigenous Australians. In the report I mentioned previously about Australian identity, participants seemed to be at a complete loss about how to talk about the first Australians. The vast majority of non-Indigenous Australians have little or no direct interaction with Indigenous peoples and their communities. We are all caught between the Qantas poster ads of smiling Koori kids and the night time news stories of violence, abuse and poverty in Indigenous communities. For some, Australia’s Indigenous heritage is the missing piece of our national story. They are looking to fill that gap with something meaningful and constructive. But in the main, there is a silence, a lack of words, a sense of hopelessness that dominates the discussion about Indigenous Australia in the rest of the community. To be honest, I think they’re trying to sort it out, but they just don’t know what to do. The honest answer is they have no idea. It’s too big a problem. You’ve taken a culture and completely fucked it up and you can’t just turn around and say, ‘we’re sorry, let’s just move on’. There’s no answer. I don’t see the answer. Just some of the common sentiments from that study on Australian identity. In his much loved and still highly relevant book, The Lucky Country, Donald Horne nailed the uniquely Australian approach to fairness. He wrote that it was “ingrained in the texture of Australian life”. Fairness was the general belief that it is the government’s job to see that everyone gets a fair go. “Fair goes are not only for oneself, but for the underdogs”, Horne wrote. Until the underdog comes out from under and then he becomes a tall poppy and can rightfully be torn down (take note Adam Goodes). There are blindsides in Australians’ kindness to underdogs, Horne pointed out. He mentioned Indigenous Australians. I would add asylum seekers. Australians, Horne writes, like “people to be ordinary”. You have to fit the “majority pattern, follow the rules”. Equality, fairness, a stake in our society and right share in its bounty can be often predicated on fitting in and not speaking out. When I think of inequality, I think of particular people I’ve met as a researcher, their stories and what they tell me about how fairness and unfairness work in this country. These are people facing multiple challenges, caught in complex webs of disadvantage. I think about a woman I met in regional NSW, a widowed mum in her 40s with six kids and a grandchild on the way. She was sleeping on the bottom part of a single trundle bed in her daughter’s room, having given up her own room for her son and his heavily pregnant girlfriend. She was struggling to access the right services in her own town, working uncertain and long shifts as a disability support worker. Gender, geography, family status and work status combined to make her life economically uncertain and stressful. I think about the foreign exchange students from India who were involved in a study I directed on the mind and mood of new migrants. They were working shitty cash in hand jobs for exploitative restaurant owners (sad to say second and third generation Indians themselves) and had paid high fees for substandard hospitality courses in this country. After all the money their parents had paid for these courses, these young men couldn’t stomach returning to India but couldn’t get ahead here in Australia either. Ethnicity, citizenship and work status combined to make their troubles seem unsolvable and invisible. The same too for a group of Sudanese refugees interviewed as part of that same study. Despite their education and ability, the only jobs they could get in our economy were as taxi drivers, supermarket trolley collectors and garbage men. In this case add skin colour and religion to the mix of forces creating unfairness for these new Australians. I think about a group of 30 something mums living 40 minutes from the centre of Melbourne. These women’s husbands had to commute long distances for their jobs and so these women were solely responsible for the child care and school shuttle run each day, not to mention supervising homework and making dinner. Despite the fact their pre-baby jobs were in sectors like financial services, they felt they had no choice but to pursue second-rate jobs (like cashiers at the local supermarket) on return to work, the assumption being these would be less demanding and more flexible. Gender and location combined to ensure these women would struggle to find skilled and well paid work again as they got older, relying heavily instead on their partners’ income and support. In the political and media talk – some of it sludge – about ‘doing it tough’, about battlers, about the aspirational class, these kinds of people and their stories rarely feature. Here is the real disconnect between perception and reality. An asylum seeker isn’t an underdog. An Indian student slaving away in a kitchen for $5 an hour is not a battler. The Australian community at large continues to hold onto the idea that we should be a fair society. They have some sense about the nature of social and economy inequality; mostly, perception of who is struggling and who is actually struggling aligns. We do worry that the gap between rich and poor is getting bigger. When government looks as if it is making decisions that will enlarge that gap, or make it harder for those who are already finding it hard, the electorate will cry out, in focus groups and polls if not at the ballot box. But do we truly understand the benefits of social equality? Or the downsides of social inequality? Do we believe governments can and want to address the causes of social and economic disadvantage? And does our mental image of inequality feature the faces of those who aren’t ‘just like us’? That is less clear. Thank you all for listening and thanks again to the Melbourne Writers Festival and The John Button Foundation for the invitation.