Dyslexia Guidance Final

advertisement

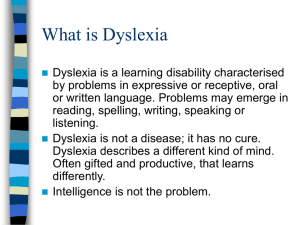

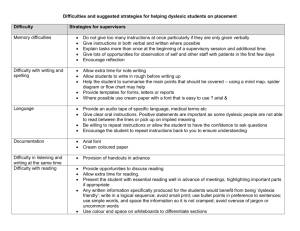

Dyslexia Guidance Department of Education and Children Rheynn Ynsee as Paitchyn September 2012 CONTENTS Section Page A Checklist of early characteristics that may indicate dyslexia 3 B Checklist of school-age indicators of dyslexia 5 C Checklist of indicators of dyslexia in adults 7 D Graduated Response 8 E Grid 5: Cognition and Learning 9 F Strategies to support the pre-school child 10 G Strategies to support the school-age student 12 H* Resources 18 * In order to reflect the most up-to-date information available about resources, Section H will be updated regularly, and may be viewed and/or downloaded from the Special Needs Wiki. Any changes to this document will be highlighted in yellow to make them easier to locate. 2 Section A Checklist of early characteristics that may* indicate dyslexia *Words of caution: The characteristics listed below will be present, to some extent, in all very young children because skills develop at different rates in different children. It is important not to read too much into the observations other than to give an indication of areas that may benefit from some additional support. Strategies to help the development of these areas may be found in Section E. 1. Family history of dyslexia 2. Speech and language: Slow speech development. Word finding difficulties. Word mispronunciation – e.g. ‘ambliance’ for ‘ambulance’, ‘pasghetti’ for ‘spaghetti’. Jumbling words. Difficulties finding words that rhyme. Difficulties finding words that start with the same letter, e.g. pretty Polly picked a ……. 3. Auditory processing: Difficulties following a rhythm, e.g. in clapping games. Difficulties remembering and following instructions, particularly if there is more than one part to the instruction, e.g. go and get teddy and put him in the basket. Difficulties learning nursery rhymes. Difficulties remembering sequences, e.g. days of the week, months of the year. 4. Unable to remember own birthday, address or phone number. Sequencing: Difficulties fastening buttons, learning to tie laces. Difficulties learning to dress, i.e. the order in which the clothes have to be put on. 3 Difficulties sorting beads by shapes. Putting shoes on the wrong foot. Difficulties turning taps on and off because of not remembering which way they have to be turned. 5. Motor skills: Difficulties learning to use scissors. Difficulties learning to hold a pencil correctly, and may continue to hold it awkwardly. Difficulties maintaining balance (especially when blindfolded), e.g. standing on one foot. Clumsiness, e.g. difficulties skipping, hopping, throwing or catching a ball. Difficulties learning to ride a bike. 4 Section B Checklist of school-age indicators of dyslexia 1. Family history of dyslexia 2. Development of reading skills: Difficulty learning to recognise words. Particular difficulty learning to recognise small prepositions, such as ‘to’, ‘by’’, ‘so’, ‘of’, and often omitting these words when reading. Struggle to learn phonics. Difficulty using phonics to help decode unfamiliar words. Poor use of context in reading. Difficulty retelling what s/he has read. Confusing words that have similar structure, e.g. reading ‘sheep’ as ‘sleep’, ‘useless’ as ‘unless’, ‘casual’ and ‘causal’. Dislike of reading. Reluctance to read for enjoyment, even when the student has ageappropriate reading skills. Difficulty interpreting written questions, and a discrepancy between his/her ability to answer a written question, and when the question is read out. Verbal/comprehension/intellectual skills considerably in advance of reading skills. 3. Development of writing skills: Difficulties learning to spell; not picking up on patterns or rules of spelling. Able to learn spellings one night, but forgetting them by the following day. Inconsistent spelling; spelling the same word differently throughout the same sentence or same piece of work. Bizarre spellings. Poor handwriting: poorly formed letters, uneven size, uneven spacing, inconsistent placement on the lines. Mixing capitals and lower-case letters. Poor punctuation. Lack of quality and quantity in written work. Verbal/comprehension/imagination/intellectual skills considerably in advance of writing skills. sequencing 5 Very slow speed of handwriting. Very quick speed of handwriting (and often difficult to read) in the older student. Finds it difficult to read back his/her own handwriting, and interpret questions based on his/her own writing. 4. Working memory deficit: Difficulty remembering what day of the week it is. Difficulty understanding the concept of yesterday/today/tomorrow. Difficulty with tasks: the alphabet, days of the week, months of the year, multiplication tables. Finds simple mental arithmetic very difficult. Difficulty remembering timetable requirements, e.g. where s/he should be, or what equipment is required on which day of the week. Forgets what homework requirements are, or forgets to do homework. Unable to remember words and phrases that are dictated. Very slow to copy from the board. Difficulty remembering instructions given verbally, particularly if they have more than one part. NB: When difficulties are first noted, the teacher/SENCo should ensure that the student has had a recent hearing test to rule out the possibility that delay/difficulty is the result of a hearing deficit, and a recent eyesight test to rule out the possibility of any visual problems. 6 Section C Checklist of indicators of dyslexia in adults 1. Family history of dyslexia 2. Reading: Difficulties following written instructions. Difficulties following technical manuals. Slow to get the gist of letters or reports etc. Forget what you have read. 3. Writing Sometimes reverse some letters, e.g. b, d. Sometimes write letters out of order, e.g. writing ‘wihch’ for ‘which’. Difficulties with spelling. Difficulties with grammar. Difficulties with punctuation. Poor handwriting. Difficulties filling in forms. Difficulties writing, e.g. memos, letters, minutes of meetings; having to change what you would like to write to what you are able to spell. 4. Forgetting what you wanted to express when you start to write. Working memory deficit Difficulties remembering: o Spoken instructions. o Telephone numbers. o Messages. o Appointments. Difficulties concentrating for long periods of time. Organisational difficulties: o Planning work schedules. o Meeting deadlines. o Keeping papers in order. o Working efficiently. 7 Section D Graduated Response 8 Section E Grid 5: Cognition & Learning Assessments Teacher based assessment Teacher observations - discrepancy between verbal and written Dyslexia checklist PM Benchmark (Decoding/Comprehension) Letters & Sounds Writing assessments Parallel Spelling Test RAP based assessment GL Assessment - Dyslexia Screener (online) Lucid LASS - 8-11 years (available on sen assessment laptop) Lucid RAPID - 4-11 years (available on sen assessment laptop) Lucid ABILITY 4-11 years (available on sen assessment laptop) Phonological Assessment Battery (PhAB) Smart Cat Learning - 4-8 years (online) www.smartcatlearning.com Interventions ICT 9 ✓ ✓ Ten Thumbs (CD) www.tenthumbstyping.com BBC Dance Mat (online) www.bbc.co.uk/schools/typing ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Text to speech - (go to system preferences - speech) Sound Studio Audio books above decoding level Kidspiration -mindmapping Dragon Dictate www.dyslexic.com ✓ ✓ ✓ Nessy Games Player (CD) www.nessy.com Nessy Learning programme (CD/downloadable) www.nessy.com Word Shark (CD) www.wordshark.com ipad applications ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Dragon Dictate Dyslexia Quest Hairy Letters Hairy Phonics (due out this spring 2012) What is dyslexia? Resources Dyslexia friendly environment & access strategies (pastel paper, reading rulers, limited copying off the board, visual strategies (Read Write Inc/Jolly Phonics) and coloured overlays etc. ✓ Use different ways of recording composition ✓ Join a guided reading group above decoding level/listen to audio books ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Active Literacy (ALK) Yes We Can Read www.yeswecanread.co.uk Five Minute Box www.fiveminutebox.co.uk Mind-Mapping HFW flashcards (for those with a good visual memory) Reference Removing Dyslexia as a Barrier to Achievement Neil MacKay www.bdadyslexia.org.uk www.dyslexiaaction.org.uk Section F Strategies to support the child at pre-school To encourage the development of speech and language: Play rhyming games, for example, make up nonsense words that rhyme with a real word, such as happy, clappy, dappy, nappy, mappy, sappy etc. Learning nursery rhymes. Playing games of snap with rhyming pairs of picture cards. Making up alliterative sentences, such as ‘Pretty Polly Perched on the Plastic Pram’, or ‘Bertie Banana Bent the Branch and Bounded up the Bank’. Playing I Spy games. Odd-one-out games with words that start with the same letter, such as ‘Silly Sam Seen Running Sideways’, and the child has to identify the word that is the odd-one-out. Sharing and reading picture/story books to the child. Talking to the child and using every opportunity to extend his/her vocabulary. For example, if the child points to and names ‘ball’, the adult could extend this and say ‘yes, that’s a big yellow ball’. To encourage the development of auditory processing: Encourage the child to identify, with eyes closed, familiar noises, e.g. rustling paper, spoon on a bowl, clink of coins etc. Sit a group of children in a circle. Choose one child to sit in the centre of the circle with his/her eyes closed. The teacher points to a child seated round the edge and this child has to whisper the name of the child who is sitting in the center. The child in the centre has to guess which child has whispered his/her name. Playing games such as ‘When I went shopping I bought a …..’ and the child has to remember an ever increasing list of items. Make sure that the speaker has the child’s full attention before giving any instructions. Ask the child to repeat back an instruction to encourage deeper processing of the information. 10 To encourage the development of sequencing skills: Encourage the child to verbalise the sequence of common actions, such as ‘Look right, look left, look right again’, or ‘First, toothbrush, second, top off the toothpaste, third, squeeze the toothpaste, fourth, brush teeth, fifth, rinse with water’. Give each child in the group a number, and then get the children to line themselves up in the correct sequence. Extend this by getting the children to muddle themselves up and then re-order. Get the children to copy a sequence of actions demonstrated by the teacher. To encourage the development of motor skills: Bead threading. Pegs and peg board. Constructing out of building blocks. Cutting-out. Therapeutic putty. Drawing, colouring, and painting Throwing and catching a soft ball. Skipping. Ride-along toys, scooters, tricycles. 11 Section G Strategies to support the school/college-age student There is no way to predict with any certainty the outcome for a dyslexic student with respect to the development of his/her lower-order literacy skills (see section 6.2.4 in the Policy). What is vitally important is that the student’s ability to access the curriculum and make good progress with his/her learning is not affected by the specific difficulties s/he has in this area. All students differ in their unique combination of patterns of strengths and weaknesses, learning styles, and learning needs, and this difference is further complicated by the changing demands of the curriculum as the student progresses through school. Each student will therefore respond to, and benefit from, different types of support and differentiation at different times in their school career. Flexibility is therefore a key issue, along with clear learning objectives and a willingness of the teachers to accept different forms of evidence of success. Of primary importance is that the dyslexic student’s self-esteem is protected. S/he is likely to be only too aware of his/her inadequacies, and will need constant encouragement to build confidence. Encouraging the student to take an active part in his/her own learning programme will help him/her become aware of what s/he needs in order to make the best progress with his/her learning possible. The following suggestions may help: Learning environment: Seating position: Encourage a dyslexic student to sit in a position in the classroom where there is the least distraction (i.e. where there will be the least pupil traffic), and where s/he is facing the board, rather than sitting side on, or with his/her back to the board. Do this discretely to avoid embarrassment. Grouping: Encourage flexible seating arrangements, for example, allow the dyslexic student to sit with students who match his/her verbal skills during activities that require discussion in class. Place the dyslexic student where support is available for activities in which s/he will require support, e.g. sit by 12 a fluent reader who can read out text when required, or with a support teacher who can act as a reader, if no electronic text reader is available. Homework: Homework can be a particularly difficult area for the dyslexic student. Avoid setting homework that requires a lot of reading and writing. Make sure that the student has the homework instructions written down fully; the easiest way to ensure this is to give out a printed sheet of instructions. Printed instructions are easier to read and complete, and remove the need to spend time copying, which is a thankless task for a dyslexic student. Make a note on the homework instructions how much time the student is expected to spend on the task. Encourage the parents, or student, to contact the teacher if homework is taking too long to complete to ensure that the student is not having to spend much longer doing homework than his/her peers. Organisation: The use of planners, homework books, home-school books, email, electronic organisers, and timetables, are all likely to help the dyslexic student to keep track of what s/he needs throughout the school week. To support reading Reading for the dyslexic student can be a very stressful activity, and s/he may be acutely embarrassed if asked to read out loud in front of his/her peers. To guard against this, the dyslexic student should only ever read out loud in class if s/he has requested that s/he does so. Text-readers: Many dyslexic students find it helpful to use the text-to-speech facility that is included on all school laptops to support his/her reading of source material used in lessons. More sophisticated, text-reading software is available, (see Section G), and the DEC is currently looking into the possibilities of making such software available centrally for the Island schools. The student should use any text-reading software in conjunction with headphones so that s/he does not disturb other students. Benefits of using this software are: The student will find it much easier to read and understand the text if s/he listens to the text being read whilst following the printed text (on screen or on hard copy). 13 The student will be able to access the same complexity of text as his/her non-dyslexic peers. The student will be able to see and understand much more complex words in print than his/her word recognition skills would normally allow. This will help his/her sight vocabulary to develop, which, in turn, will help his/her word recognition skills to develop. The student will develop better listening skills which, s/he will need should s/he be granted access arrangements that include a reader for examinations. Audio books: Reluctant readers should be encouraged to listen to a wide range of age-appropriate and interesting audio books for the benefits listed in section 6.2.1.3 in the Policy. Encourage the dyslexic student to listen to audio books for Guided Reading tasks or during silent reading times at school. Paired reading techniques, where a fluent reader reads aloud with the dyslexic student, can help to build confidence in reading. To support accessing information, dyslexic students are very likely to derive benefit from the use of film, imagery, diagrams, and schematics to support their learning. Some individuals find it helpful to cut out the white glare from white paper, either by using a coloured overlay (See Section G), or by printing the text onto off-white paper. *** To support writing Give credit for oral responses. Mark written work on content. Photocopy notes, and/or print out work from the teacher/s notes for the dyslexic student to stick in his/her book. Copying from the board or from a 14 book is a thankless task for a dyslexic student, and the result can be difficult to read back, inaccurate and incomplete, and the process often causes frustration. Be flexible in the type of evidence you will accept to prove that the student has met the lesson objective. Some students will find it easier to present written work in bullet points, via a mind-map, using word processing, making a sound file, or using voice-to-text software to produce hard copy. Touch-typing: If the dyslexic student is able to learn to touch type proficiently, s/he may find that s/he is able to bypass a persistent spelling difficulty by learning to, literally, spell with his/her fingers. For this to happen, it is essential that the student follows the lessons in a typing tutor without looking at his/her fingers. This is to stimulate the brain into making new neural pathways in which a word is typed by a pattern in which the fingers move, rather than being written by which letters are needed. There are some excellent touch typing tutors available (see Section G), and a large breakfast cereal box, which has had its long thin sides cut out and the open end taped shut, is an ideal shape to slip over the keyboard of a laptop to prevent the student from being able to look at his/her fingers whilst following the instructions on screen. Word processing: If the student is able to type more easily than write, encourage him/her to use a word processor, with predictive text, and spell checker to compose any written work. The benefits of working in this way are: The hard copy produced when working with a word processor is neat and easy to read back. Many dyslexic students find that they gain in confidence when they work on a word processor with predictive text and a spell checker. The student is able to set their ideas down in any order, and can then use the edit tools to order the work. Working on a word processor in this way prepares the student for using this method of working in any examinations (see section 7 in the Policy) 15 Voice-recording software: The student may find it helpful to use voice recording software. The benefits of working in this way are: It enables the student to express his/her knowledge or ideas in a way that is not hindered by any spelling difficulty. The student is able to listen back and edit the recording, which means that the ability to edit the work does not depend on the level of the student’s reading skills. Having to listen back to the recording will help with the development of the student’s listening skills. After learning how to use the software or device, the student is able to work independently. Working in this way helps the student to develop oral composition skills, and this is good preparation for using access arrangements in examinations (see section 7 in the Policy). If the student is proficient at touch-typing, s/he could listen to his/her recording through headphones and type up a hard copy. Voice-to-text software: The dyslexic student may find it helpful to learn to use voice-to-text software (see Section G). The benefits of working in this way are: It enables the student to express his/her knowledge or ideas in a way that is not hindered by any spelling difficulty. After learning how to use the software or device, the student is able to work independently. If the student has poor reading skills, the voice-to-text software can be used in conjunction with text reading software. Learning to use these types of software helps the student to develop the necessary skills s/he will need for working in this way during examinations (see section 7 in the Policy). Mind-mapping skills: Many dyslexic students find it helpful to use mindmapping as a way of ‘capturing’ and ordering his/her ideas prior to writing/dictating. Some benefits of using mind-maps are: The student is less likely to forget what s/he planned to include if s/he works from the mind-map when writing/dictating. 16 The complexity of ideas can often be expressed in a way that is not hindered by the student’s spelling ability. The student will have more working memory capacity available once the ideas being held there are put down on paper in the mind map. This means that there will be more working memory capacity available for the student to apply to the quality of his/her composition. Some resources for developing mind-mapping skills may be found in Section G. To support a working memory deficit: Strategies to support working memory, such as the use of min-mapping approaches, are outlined above. The student should be encouraged to use any additional time granted in assessments to write out such aids as multiplication tables, formulae (where necessary), quotes, names and dates. Once these are captured on paper, they may then be referred to during the assessment. Because they no longer have to be remembered, the working memory is emptier and has more capacity to apply to other tasks. Protect self-esteem It is vitally important that the dyslexic student learns to equate his/her thinking skills, ideas, and creativity, with his/her ability, and does not start to equate his/her ability with the level of his/her word recognition and spelling skills. Take every opportunity to praise the dyslexic student for effort; s/he is likely to have made considerably more effort than his/her peers, even though s/he has not achieved the same standard. Dyslexic students get very tired because of the amount of additional concentration and effort they have to put in to keep up with a text-based curriculum. Extra allowances need to be made to take this into account. 17 SECTION H Resources Useful contacts Manx Dyslexia Association www.manxdyslexia.org Tel: 07624 315 724 British Dyslexia Association www.bdadyslexia.org.uk Dyslexia Action www.dyslexiaaction.org.uk Dyslexia Scotland www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk Department of Education for Children: Director of Services for Children Department of Education and Children Hamilton House, Peel Road, Douglas IM1 5EP Tel. 693833 Sally Brookes Educational Psychology Service Joanna Fisher Joyce Monroe Senior Educational Psychologists Jonny Fee Helen Newbery Educational Psychologist Educational Psychologist in training Department of Education and Children, Hamilton House, Peel Road, Douglas IM1 5EP Tel: 686271 Advisory Teachers Lizzie Corrin Sue Marriott SEN Advisors Julie Wilsdon Advisory teacher ICT 18 Department of Education and Children, Hamilton House, Peel Road, Douglas IM1 5EP Tel: 686271 Department of Education and Children, Hamilton House, Peel Road, Douglas IM1 5EP Tel: 686389 Resources: To support reading Kurzweil 3000 Further information www.sightandsound.co.uk. Texthelp Read & Write www.sightandsound.co.uk Gold Features Advanced text-reading software with many other features to help students access and express themselves through text. Many other features available, such as mind-mapping tools, bubble notes, voice notes, highlighting facility. May be used in conjunction with Dragon Dictate so that the student can dictate work and then have the text-reader read it back to them. Software that reads out loud as the student types. Provides full screen reading for any document on the laptop or computer. This also has other features to help with reading and writing. Easy to use click-to-read facility. Textease www.textease.com Text-to-speech IT Department Easy to use, slightly robotic voices – on all DEC Apple laptops. Wordtalk www.wordtalk.org.uk Free Windows text-to-speech plugin for Microsoft Word. This software will speak the text on a document and highlight each word as it is read. Speak it App for iPad www.apple.com Text-to-speech app for iPad or iPad. 19 To support writing Further information Features Dragon Dictate for Mac; Dragon Naturally Speaking for PCs www.dyslexic.com Speech-to-text software. Requires voice training that can be tricky for young voices to be recognised. Dragon Dictation www.apple.com Free app for iPad or iPod. Very easy to use – requires no voice training. Textease www.textease.com Write anywhere facility; voice recording, easy to use. Clicker 5 www.cricksoft.co/uk Text-to-speech working with Clicker grids. Writeonline www.cricksoft.co.uk Word processing software that provides text-to-speech, predictive words, & wordbars to help the student to write without being hindered by spelling difficulties Inspiration www.dyslexic.com Mind mapping software for the older student. Very good templates for many types of written requirements for all subject areas. Kidspiration www.dyslexic.com Mind mapping software for the younger student. All text and pictures spoken aloud; voice recording facility; can import pictures to make personalised dictionaries. Novamind www.novamind.com Mind mapping software. iMindmap www.thinkbuzan.com/uk Mind mapping software. Books by Eva Hoffman Excellent classroom resources for teaching students to mind map. To support mindmapping Mind-mapping in Primary Classrooms Introducing Mind Mapping to Children Mind Mapping for Kids Resources for teaching mind mapping and revision skills. Max Your Memory and Books by Tony Buzan Concentration Rev up for Revision 20 Touch typing Further information Features Englishtype Junior or www.dyslexiaaction.org.uk Senior Programme written with dyslexic students in mind. Very well organised, quiet, reinforces all the right areas, low levels of time stress. Ten Thumbs www.tenthumbstypingtutor.com BBC Dancemat www.bbc.co.uk/schools/typing This programme saves each child’s progress and gives feedback in terms of % success. Free to use but very noisy and busy programme. Liked by some children. Mavis Beacon www.mavisbeacon.com Good established touch typing programme that has been around for a long time. Audio Books Children’s Library, May be borrowed e.g. Westmorland Road, Douglas. from local libraries May be borrowed e.g. from on-line libraries: www.listening-books.org.uk www.calibre.org.uk For an annual subscription (which they may waive for cases of financial hardship) books can be streamed to laptop or computer. Can also be downloaded for a limited time, or sent out as MP3 discs to your home. Excerpts of books may be listened to on site. This site has many school text books on audio. As yet, this site only works with PCs but will be making the service available to Mac users in the future. Calibre audio library is a charity that will send out for free 3 MP3 discs of your choice to your home with a return envelope. They will send more discs when the first are returned. Excerpts of books may be listened to on site. May be bought and e.g. downloaded from on- www.audible.co.uk www.apple.com/itunes line bookstores. Audio books can be bought and downloaded onto a laptop or computer and then transferred to an MP3 or MP4 player, such as an iPod, for ease of listening. Excerpts of books may be listened to on site. May be downloaded www.load2learn.org.uk from on-line educational sites: Provides accessible curriculum resources for students who have difficulty accessing text. www.amazon.co.uk www.waterstones.com 21 Resources for improving reading and Further information spelling Various resources that www.nessy.com can be bought online for students to engage with at home. Coloured overlays www.crossboweducation.com www.dyslexic.com Other useful resources Information sheets for teachers and parents from Dyslexia Scotland. Training pack for teachers from Education Scotland. Features Fun games for the laptop aimed at improving spelling and reading skills. Some students find it easier to read text if it is covered with a coloured plastic overlay. www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk Follow the link for ‘educator’, ‘guidance and training’, and click on the pdf files in the paragraph titled ‘The right support’ www.educationscotland.gov.uk and type in ‘supporting learners with dyslexia’ into the search engine on this site. This should come up with a pdf file Journey to Excellence Personal Development Pack – Meeting the needs of learners with dyslexia. 22