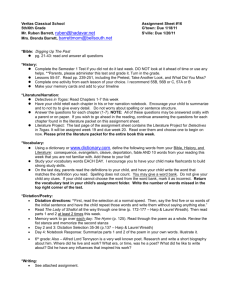

New: Powerpoint format biography

advertisement

Rufus King: A Biography The Early Years Rufus King was born on a farm on March 24, 1755 in Scarborough, Maine (then part of Massachusetts.) He was the eldest son of Captain Richard King, a successful merchant, and his first wife, Isabella Bragdon. At the age of 12, Rufus was sent to Dummer Academy, one of the first private boarding schools in colonial America. King entered Harvard College during the summer of 1773 at the age of 18. In 1776, as Rufus entered his last year at Harvard, the Declaration of Independence was signed, telling King George III that the colonies now considered themselves free from British rule. After Rufus graduated from Harvard first in his class, he studied law and served in the American Revolution. By 1783, the American colonists had defeated the British troops. Rufus, already a successful lawyer, entered state politics in Massachusetts. Rufus King: Public Servant After serving in the Massachusetts government for several years, Rufus was selected to represent Massachusetts in the Confederation Congress, the new national government of the United States. This government existed before George Washington became President, and the capitol was New York City. By 1787, it was obvious to many Americans that there were problems with the government under the Articles of Confederation. Rufus was one of the men Massachusetts selected to travel to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia to make a new American government. Rufus was picked to be one of five men to write the Constitution and that autumn signed it for Massachusetts. Soon after the convention, Rufus moved to New York and was elected to the New York Assembly. He was then chosen to become one of the first Senators representing New York. After serving in the Senate for 7 years, Rufus was appointed by President George Washington to be the United States Ambassador to England. He and his family sailed to England, where they lived until 1803. When he returned to the United States, Rufus began looking for a farm to buy and continued his political career. Jefferson Pinckney In the autumn of 1804, King was the Federalist party’s nominee for VicePresident, with Charles C. Pinckney as the Presidential nominee. The two men lost to Thomas Jefferson and New Yorker George Clinton. Rufus and Charles Pinckney ran again in 1808. Although they did better in this election than in 1804, James Madison and George Clinton were reelected. Madison In 1813, New York again selected Rufus King to serve in the United States Senate. In 1816, he lost to James Monroe in the Presidential election, becoming the last Federalist candidate for the Presidency. Monroe He continued to serve in the Senate until 1825, when he again traveled to England as the United States ambassador. Rufus’s years in the Senate were very busy. He spent a lot of time working on laws and considering how the United States should interact with countries around the world. He also spent a lot of time with or writing to his family and loved his farm in Jamaica, Queens. Rufus King: Family and Farming When Rufus first moved to New York, he lived in the home of John Alsop and his daughter Mary Alsop. Mary was described as “kind and benevolent” and was said to be “the best looking woman in New York City.” Rufus and Mary’s wedding was described as “the top wedding in the country.” Mary was “...remarkable for her personal beauty, her motions were grace, her bearing gracious, her voice musical, and her education exceptional.” Rufus and Mary eventually had five sons: John, Charles, James, Edward, and Frederick. When Rufus moved back to New York from England, he brought with him an interest in farming as science. He told his sons, “I MUST have a farm.” In 1805, Rufus found the farm he wished to buy. He wrote to his son John: “I have purchased a place in the country, at the village of Jamaica. The house is not fashionable but convenient...” Rufus’s son Charles later wrote that “time and money were liberally applied” in planting the grounds. In addition to crops like wheat and asparagus, thousands of trees were planted. Pines and firs from New Hampshire, elms from Massachusetts, and fruit trees from nurseries in Flushing were planted. Some trees planted in 1810 grew and are today towering red oaks not far from the house. Rufus originally told his sons that there was sufficient and good land for cattle to graze, and he chose to import a herd of Devon cattle from England. King Manor was a busy working farm, and Rufus was a gentleman farmer who supervised the work taking place on his farm. Farming takes a lot of work, and Rufus hired, rather than enslaved, many farmers and gardeners to help take care of his property and its plantings. Opposing Slavery Slavery was still legal in New York when Rufus King bought King Manor. He had to choose whether he wanted to hire farmers and other servants or if he wanted to buy slaves to work on his property. He chose to hire people. Sometimes his servants came from the local area and other times they moved here from other places to work for Rufus. Slavery was a political issue, too – and a very controversial one. During Rufus King’s last term in the Senate, he took a strong stand against slavery. In 1819-1820 he argued in the Senate against the admission of Missouri as a state that allowed slavery and fought against the Missouri Compromise of 1820. On the floor of the Senate, Rufus spoke out against slavery, saying: “I have yet to learn that one man can make a slave of another...if one man cannot do so, no number of individuals can have any better right to do it...” Rufus suggested that states use money from the sale of public lands for the emancipation of slaves. John Quincy Adams, who would become our 6th President, wrote in his diary about the affect of Rufus King’s powerful anti-slavery speeches: The slave owners “...gnawed their lips and clenched their fists as they heard him ....the slaveholders cannot hear of him without being SEIZED WITH CRAMPS.” Rufus King probably isn’t the name you think of first when you think of the end of slavery. That’s partly because it still took many years for slavery to end. Rufus wrote, however, that one speech can become the foundation of another. Sometimes change, he knew, required a lot of people saying that something needs to change. He was one of the first statesmen in the world to publicly say that slavery was wrong. Beyond Rufus King Rufus’s eldest son John Alsop King married Mary Ray and together they had 8 children. John loved farming, just as his father did, and when Rufus died in 1827, John and his family moved into King Manor. His daughter Cornelia was the last member of the King family to live in this house. Like Rufus, John entered politics and he, too, spoke out strongly against slavery. John was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, the New York State Assembly and Senate, and served as Governor of New York State. Charles King had a very successful career and was a newspaper editor. Later in his life, Charles was President of Columbia College, now Columbia University. Charles married Eliza Gracie and, when she died, married Henrietta Liston Low. Charles had a total of 14 children. James Gore King was a successful banker, nicknamed the “Merchant Prince of Wall Street.” James married Sarah Gracie King (the sister of Charles’s wife Eliza) and together they had 12 children. From 1848-1850, James represented New Jersey in the U. S. House of Representatives. Edward King moved to Ohio when he was just twenty years old. He married Sarah Worthington and had five children. Edward was a lawyer and founder of Cincinnati Law School. Frederick King studied science and became a well-respected doctor. He married Emily Post, but they had no children. Frederick died of yellow fever at the age of 27. King Manor was purchased by the village of Jamaica in 1897. When Queens became part of New York City in 1898, the last 11 acres around it became King Park. King Manor opened as a museum in 1900. www.kingmanor.org