Projet WHEAFI (WHEAT ACTIVE FIBRE)

advertisement

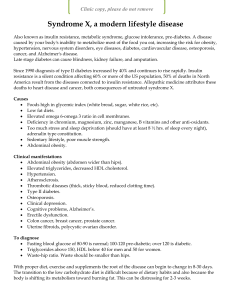

Diet and Metabolic Syndrome: Practical Approaches to Lowering Risks of Heart Disease and Diabetes Kevin C. Maki, PhD, FNLA, FTOS Midwest Center for Metabolic & Cardiovascular Research and DePaul University Chicago, Illinois The Metabolic Syndrome A cluster of risk factors for heart disease and type 2 diabetes that occur together more than would be predicted by chance Has been known by several names: – Syndrome X – Insulin Resistance Syndrome – The Deadly Quartet Metabolic Syndrome: Prevalence in U.S. by Age – 2001 ATP III Defn. Men Women 40-49 50-59 Prevalence (%) 50 40 30 20 10 0 20-29 30-39 Age (years) Ford, et al. JAMA. 2002;287:356-9. 60-69 70+ Metabolic Syndrome Definition (AHA/NHLBI Revised) Any three of the following: – Abdominal obesity: waist circumference >102 cm (40 inches) for men > 88 cm (35 inches) for women – Triglycerides: ≥150 mg/dL (or meds) – HDL cholesterol (or meds) < 40 mg/dL (men) < 50 mg/L (women) – Blood pressure: ≥130/85 mmHg (or meds) – Fasting glucose: ≥100 mg/dL (or meds) Additional Features of the Metabolic Syndrome (Under the Surface) Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia Small, dense LDL particles (Pattern B) Pro-thrombotic and inflammatory states – ↑ fibrinogen – ↑ plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 – ↑ C-reactive protein Elevated uric acid Hypertrophy or hyperplasia – Heart, blood vessels, prostate, tumors Diabetes Mellitus: a US Pandemic • Diabetes mellitus affects 25.8 million people or 8.3% of the US population (1/3 undiagnosed) • It is estimated that 79 million US adults have prediabetes • Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a major cause of heart disease and stroke, and is the leading cause of kidney failure, lower-limb amputations, and blindness • Annual economic impact (direct and indirect): $174 billion http://www.ndep.nih.gov/diabetes-facts/#howmany Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes: the Traditional Triumvirate HGP = hepatic glucose production DeFronzo RA. Diabetes. 2009;58:773-795. Glucose and Insulin Responses During 100 g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) 180 Plasma Insulin (mU/L) Plasma Glucose (mg/dL) 130 120 110 100 90 80 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 Normal 160 60 120 Time (min) Insulin Resistance 0 Normal Maki KC. Unpublished data. 60 120 Time (min) Insulin Resistance Matsuda Index * AUC ins/glu Beta-Cell Function in NFG, IFG, and Diabetes Oral disposition index 1400 1200 1000 All comparisons p < 0.001 800 600 400 200 0 NFG IFG Maki KC, et al. Nutr J. 2009;8:22. Diabetes Glucose and Insulin Responses During a Liquid Meal Tolerance Test 300 200 150 100 NFG IFG Diabetes 140 Insulin (mU/L) 250 Glucose (mg/dL) 160 NFG IFG Diabetes 120 100 80 60 40 50 20 0 0 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 210 240 Time (min) 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 210 240 Time (min) NFG = normal fasting glucose, IFG = impaired fasting glucose Maki KC, et al. Nutr J. 2009;8:22. Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes: Quartet of Essential Defects DPP-IV = dipeptidyl peptidase-4 TZDs = thiazolidinediones DeFronzo RA. Diabetes. 2009;58:773-795. Role of Nocturnal Free Fatty Acids (FFAs) in DietInduced Obesity/Insulin Resistance in Dogs Dashed lines indicate 9:00 am feeding Open bars are pre- and filled bars are postdiet-induced obesity Kim SP, et al. Am J Physiol Endocr Metab. 2007;292:E1590-E1598. Raising FFA Induces Insulin Resistance in Healthy Subjects FFA level (µmol/L) • Saline n = 422 • Intralipid n = 588 LBM = lean body mass Mathew M, et al. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2010:9:9. Lowering FFA with Acipimox Increases Insulin Sensitivity Cusi K, et al. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1775-E1781. Relation Between Weight Loss and Insulin Sensitivity According to Dietary CHO SSPG = steady-state plasma glucose McLaughlin T, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:813-821. Defects in Dysglycemia: Muscle, Liver, Pancreas, Adipose Tissue • Insulin resistance Reduced ability of a given circulating level of insulin to enhance tissue uptake of glucose (particularly in skeletal muscle) Reduced ability of a given circulating level of insulin to suppress hepatic glucose output and release of FFA from adipose depots • Excessive hepatic glucose output Hepatic insulin resistance Excess glucagon release + other factors (e.g., neural control) • Pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction Reduced insulin response to a rise in plasma glucose Reduced sensitivity to glucose signaling Incretin resistance and deficiency Lower insulin secretion capacity in advanced T2DM Risk Factors for Diabetes Pre-diabetes (IGT, IFG, elevated HbA1C) Overweight/obesity Physical inactivity Age ≥45 y Family history of diabetes Metabolic syndrome and its components Certain racial and ethnic groups (e.g., Non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanic/Latino Americans, Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, American Indians and Alaska natives) Women who have had gestational diabetes, or given birth to a baby weighing ≥9 lbs http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/prevention/risk-factors/ Pre-Diabetes Test Range of values Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) 100-125 mg/dL 2-hr plasma glucose, 75 g OGTT 140-199 mg/dL Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) 5.7-6.4% ADA. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S62-S69. Diabetes Prevention Studies Overview: Hypoglycemic Agents Study Subjects Total N F/U (y) Intervention Diabetes Risk ↓ U.S. DPP IGT 3234 2.8 0.9 Metformin Troglitazone 31% 75% India DPP IGT 531 2.5 Metformin Metformin + diet/exercise 26% 28% India DPP-2 IGT 407 3.0 Pioglitazone NS U.S. ACT NOW IGT 602 2.4 Pioglitazone 72% U.S. TRIPOD Prior GDM 236 2.5 Troglitazone 55% Sweden XENDOS IGT or NGT 3305 4.0 Orlistat + diet/exercise 45% Canada DREAM IGT 4894 3.0 Rosiglitazone 58% Canada CANOE IGT 207 3.9 Rosiglitazone + metformin 66% EU/Can Stop-NIDDM IGT 1429 3.3 Acarbose 25% ACT NOW = Actos Now for the prevention of diabetes; TRIPOD = TRoglitazone in the Prevention Of Diabetes; XENDOS = XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects; DREAM = Diabetes REduction Assessment with rampiril and rosiglitazone Medication; CANOE = CANadian Normoglycemia Outcomes Evaluation Diabetes Prevention Studies Overview: Lifestyle Modification Study Subjects Total N Followup (y) Intervention Diabetes Risk ↓ US DPP IGT 3234 2.8 Diet + exercise 58% China Da Qing IGT 530 6.0 Diet Exercise Diet + exercise 35% 39% 32% Finland DPP IGT 522 3.2 Diet + exercise 52% India DPP IGT 531 2.5 Diet + exercise 29% Japan DPP IGT 458 4.0 Diet + exercise 67% Spain PREDIMED CHD risk factors (≥3) 418 4.0 Olive oil- or Nut-based Mediterranean diet 43% 39% CHD = coronary heart disease DPP = Diabetes Prevention Program PREDIMED = Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Targets: 7% Weight Loss, 150 min/wk Activity DPP N Engl J Med 2002; 346:393-403. Effect of Lifestyle Changes (Diet and Exercise) on Incidence of T2DM A review of studies of 4864 high-risk individuals followed for 2.5-6 y reported – Lifestyle changes may lower incidence of T2DM by 28-59% – 6.4 individuals need to be treated to prevent or delay 1 case of diabetes through lifestyle changes (over 3-4 years) – Various weight loss diets (low fat, high protein, or Mediterranean) may be effective (weight loss more important than how achieved) – Maintenance of weight loss requires regular exercise with additional expenditure of ~2000 kcal/week (~15 miles of walking) Walker KZ, et al. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23:344-352. Meta-Analysis: Estimates of Associations Between Macronutrient Intake and T2DM Risk CHO analysis: 10 cohort studies; fat analysis: 14 cohort studies; protein analysis: 4 cohort studies Macronutrient Relative Risk 95% Confidence Interval (CI) Carbohydrate* 1.11 1.01, 1.22 Fat 0.93 0.86, 1.01 0.76 0.68, 0.85 1.02 0.91, 1.15 Vegetable Fat† Protein * A high vs. low intake of total CHO was associated with higher risk of T2DM (p = 0.035). † A high vs. low intake of vegetable fat was associated with lower risk of T2DM (p < 0.001). Alhazmi A, et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012;31:243-258. Risk of Developing T2DM Associated with Increased Glycemic Index and Load Results for glycemic load were similar to those for glycemic index. Glycemic load is affected by carbohydrate intake and glycemic index. Barclay AW, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:627-637. Dietary Fibers and Diabetes Risk Schulze et al. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:956-965. Nurses Health Study: Relative Risk of T2DM by Different Levels of Cereal Fiber and Glycemic Load Salmeron J, et al. JAMA. 1997;227:472-477. Resistant Starch Intake Increases Insulin Sensitivity in Overweight and Obese Men HAM-RS2 = high-amylose maize type 2 resistant starch SI = insulin sensitivity Maki KC, et al. J Nutr. 2012;142:717-723. Effect of Short-Term (24 hr) Resistant Starch Consumption on Breath H2 and FFA (NEFA) Closed symbols are control and open symbols are resistant starch Robertson MD, et al. Diabetologia. 2003;46:659-665. Fermentable Dietary Fiber and Insulin Sensitivity Sleeth et al. Nutrition Research Reviews 2010;23:135–145 Food Sources of Fermentable Fibers Oats and barley (beta-glucan) Prunes, apples and pears (pectin) Nuts and seeds Legumes Multi-grain breads (those with ≥3 g fiber per slice) Sugar Sweetened Product Consumption Reduce Insulin Sensitivity Parameter Baseline Dairy (Δ) SSP (Δ) Difference P-value* Mean (SEM) or Median (Q1, Q3) 4.16 -0.10 -0.49 MISI HOMA2-%S (2.81, 5.98) 117.8 (-0.96, 0.54) 1.3 (-1.01, 0.14) -21.3 (86.2, 147.1) (-21.3, 29.3) (-33.1, -3.30) 0.39 0.290 22.6 0.009 Dairy = 2 servings per day of 2% milk and 1 serving of yogurt SSP = 2 servings per day of sugar-sweetened cola and 1 serving of non-dairy pudding Maki et al. Experimental Biology 2014 Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; HOMA2-%B, homeostasis model assessment 2-β-cell function; HOMA2-%S, homeostasis model assessment 2-insulin sensitivity Matsuda insulin sensitivity index; SSP, sugar-sweetened products. *P-values were calculated from a repeated measures ANCOVA model between dairy and SSP conditions (N = 34). Differences in Lipids and 25-OH Vitamin D Between Dairy and Sugar-sweetened Product Conditions Parameter* Baseline (mg/dL) Dairy (%Δ) SSP (%Δ) Difference P-value* Mean (SEM) or Median (Q1, Q3) LDL-C 125.7 (5.82) -0.0 (2.2) -0.1 (2.2) 0.1 0.947 Non-HDL-C 153.4 (6.95) -0.4 (2.0) 0.5 (2.2) -0.9 0.752 TC 196.7 (6.81) -0.6 (1.5) -0.7 (1.5) 0.1 0.953 44.3 (1.53) 0.8 (2.0) -4.2 (1.3) 5.0 0.015 133.2 (7.33) -2.0 (4.7) 6.0 (4.6) -8.0 0.209 24.5 (2.2) 11.7 (5.6) -3.3 (3.4) 15.0 0.022 HDL-C Triglycerides 25(OH)D (ng/mL) Abbreviations: -C, cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein, LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SSP, sugar-sweetened products; TC, total cholesterol. *P-values were calculated from a repeated measures ANCOVA model between dairy and SSP conditions (N = 34). Dietary Macronutrient Composition and T2DM Risk Macronutrient changes and T2DM risk Reduce intakes of foods high in refined carbohydrates (CHO) Sugars and refined starches Potential options for substitution CHO-rich foods with low glycemic index, particularly whole grains that contain cereal and fermentable fibers Fats (particularly vegetable fats) Proteins Alcohol High Cereal Fiber or Moderate Cereal Fiber and Moderate Protein Diet Improves Insulin Sensitivity Nutrient Control High cereal fiber (HCF) High PRO (HP) Mix CHO, % energy 55 55 40-45 45-50 PRO, % energy 15 15 25-30 20-25 Fat, % energy 30 30 30 30 Dietary fiber, g ~20 ~50 ~20 ~35 Values are % of baseline, 3 = sig diff from HP, 4 = sig diff from baseline N = 111 overweight adults; M value = insulin-mediated glucose uptake as a measurement of whole-body insulin sensitivity; EGP = endogenous glucose production Weickert MO, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:459-471. Meta-Analysis of 74 Trials of High Protein vs. Lower Protein Diets on Health Outcomes Santesso N, et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:780-788. Potential Mechanisms for Higher Protein Diets and Weight Loss Hu FB. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82 (suppl):242S-247S. Energy Expenditure Higher After Protein vs. CHO Intake Acheson et al., Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:525-534 Appetite Visual Analog Scale Ratings Following Low vs. High Protein Breakfasts N = 34 healthy women; randomized controlled crossover trial 30 and 39 g protein produced greater appetite control throughout the morning vs. NB and LP (p < 0.001) LP = low protein breakfast (3 g protein), NB = no breakfast (water only) Rains TM, et al. Poster presented at The Obesity Society. November, 2013. Energy Intakes at Lunch Following Low vs. High Protein Breakfasts N = 34 healthy women; randomized controlled crossover trial LP = low-protein breakfast (3 g protein), NB = no breakfast (water only) Different letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05); energy intake at lunch for 30 g Pro vs. LP was p = 0.053 Rains TM, et al. Poster presented at The Obesity Society. November, 2013. Effect of a Reduced Glycemic Load Diet (Lower CHO, Higher Protein and Fat) on Weight Loss ♦ Control diet (low-fat, portion control – 46/19/37% CHO/PRO/Fat) ■ Reduced glycemic load diet (32/26/42% CHO/PRO/Fat) Maki KC, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:724-734. POUNDS LOST: All Diets Resulted in Clinically Meaningful Weight Loss, But… Macronutrient intake targets at 6 and 12 months were not met N = 811 overweight adults Sacks FM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:859-873. POUNDS LOST: Targeted Differential PRO Intake Was Not Achieved Intake/d Low Fat/ Average PRO Low Fat/ High PRO High Fat/ Average PRO High Fat/ High PRO 6 mo 2y 6 mo 2y 6 mo 2y 6 mo 2y CHO, % 57.5 53.2 53.4 51.3 49.1 48.6 43.0 42.9 PRO, % 17.6 19.6 21.8 20.8 18.4 19.6 22.6 21.2 Fat, % 26.2 26.5 25.9 28.4 33.9 33.3 34.3 35.1 Targets Sacks FM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:859-873. Protein and Glycemic Index in Weight Loss Maintenance 548 participants completed the study Results suggest that the high-protein, low glycemic index diet may help to reduce weight regain, although the effect was modest (3-4 lb) LP = low protein (13% en) HP = high protein (25% en) LGI = low glycemic index HGI = high glycemic index Larsen TM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2102-2113. Optimal Macronutrient Intake Trial to Prevent Heart Disease (OmniHeart) N = 164 individuals with prehypertension or stage 1 hypertension without diabetes Each feeding period lasted 6 wks, and body weight was kept stable Targets (% kcal) CARB PROT UNSAT CHO 58 48 48 PRO 15 25 15 Fat 27 27 37 MUFA 13 13 21 PUFA 8 8 10 SFA 6 6 6 CARB: carbohydrate-rich diet similar to Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension PROT: replacement of 10% of CHO calories with PRO (mixed source) UNSAT: replacement of 10% of CHO calories with unsaturated fats MUFA = monounsaturated fatty acids PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acids SFA = saturated fatty acids Appel LJ, et al. JAMA. 2005;294:2455-2464. OmniHeart: Results for Measures of Insulin Sensitivity Baseline (BL) Mean UNSAT vs CARB PROT vs CARB UNSAT vs PROT Mean (95% CI) between-diet from BL QUICKI 0.35 0.005* (0.000, 0.009) 1/HOMA-IR 0.74 0.11* (0.03, 0.20) 0.001 (-0.004, 0.007) 0.003 (-0.002, 0.009) 0.04 (-0.07, 0.14) 0.08 (-0.05, 0.20) *p < 0.05 (for 1/HOMA-IR the increase compared to CARB was ~15%) QUICKI = quantitative insulin sensitivity check 1/HOMA = homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance reported as the reciprocal Gadgil MD, et al. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1132-1137. Other Dietary Factors Associated with Lower Risk of T2DM – Need More Research Before Specific Recommendations Coffee – Especially in place of sugar-sweetened beverages Polyphenols – Found in some foods and beverages – Berries, cherries, cranberries, coffee, tea, cocoa Cinnamon – High doses of cinnamaldehyde Magnesium – High levels in whole grain foods Chromium Dairy foods (esp. fermented dairy products) Moderate alcohol consumption Dietary Supplements and Diabetes Despite an increasing body of literature investigating the use of natural [dietary] supplements on the treatment of diabetes, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) does not recommend their use because: – Clinical evidence showing efficacy is insufficient – Standardized formulations are [often] lacking Allen RW. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):452-459 Theoretical Causal Model for Effects of Coffee on Risk of T2DM COFFEE Chlorogenic acids Trigonelline Quinides Micronutrients GUT GIP GLP-1 Glusose absorption Iron LIVER absorption G-6-Pase Gluconeogene sis Inflammation Oxidativ e stress β-cell function Glycemic control Insulin resistance T2D Coffee Intake and Reduced Risk of T2DM: Potential Mechanisms? Anti-inflammatory (Frost Anderson, Jacobs, et al. AJCN 2006) – Coffee is a rich source of minerals and phytochemical compounds, including phenolics, that may confer protection from systemic inflammation Systemic inflammation has been found to predict type 2 diabetes independent or traditional risk factors Antioxidants (Svilaas et al., J Nutr 2004) – Coffee is a rich source of antioxidant compounds, may confer protection from oxidative stress Oxidative stress is elevated in obesity and type 2 diabetes Polyphenols Natural phytochemical compounds in plant-based foods (such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, cereal, legumes, tea, coffee, wine and cocoa) More than 8000 polyphenolic compounds have been identified Several biological activities and benefits have been documented: – Examples include: Antioxidant Anti-allergic Anti-inflammatory Anti-viral / anti-microbial May modulate important cell signaling ways: – Examples include: Nuclear factor kappa-β (NF-κβ) Activator protein-1 DNA binding (AP-1) Extracellular signal-related protein kinase (ERK) Bahadoran Z. J Diab Met Disor. 2013;12:43-52 Polyphenols: 2 Major Categories Phenolic Acids (1/3 of polyphenolic compounds in diet) – Hydroxybenzoic acid derviatives Protocatechuic acid Gallic acid p-hydroxybenzoic acid – Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives Caffeic acid Chlorogenic acid Coumaric acid Ferulic acid Sinapic acid Flavonoids (the most abundant polyphenols; more than 4000 types identified) – – – – – – Anthocyanins Flavonols Flavanols Flavanones Flavones Isoflavones Examples of Food Sources of Polyphenols Phenolic acids – – – – – – – Berry fruits Kiwi Cherry Apple Pear Chicory Coffee Flavonoids – Anthocyanins: berries family, red wine, red cabbage, cherry, black grape, strawberry – Flavonols: onion, curly kale, leeks, broccoli, blueberries – Isoflavones: soybeans and soy products Cinnamon Hypothesized to provide health benefits, such as lowering serum lipids and blood glucose Proposed active component: cinnamaldehyde – Insulinotropic effects have been investigated, thought to be responsible for: Promoting insulin release Enhancing insulin sensitivity Increasing insulin disposal Exerting activity in the regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1β (PTP1β ) and insulin receptor kinase Results of 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effects of cinnamon on glycemia and lipid levels: – Statistically significant reductions in fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, LDLcholesterol, and triglycerides; statistically significant increase in HDL-cholesterol – No effect on hemoglobin A1c Allen RW. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):452-459 Magnesium Prospective studies those with higher Mg intake are 10-47% less likely to develop T2DM – Only 50% of Americans (1 yr+) achieve recommended dietary allowance for Mg (400-420 mg/day for adult men & 300-310 mg/day for adult women) Results from several clinical trials (short duration, ≤ 6 months) of Mg in those with and without diabetes found that supplementation may improve: – Glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, beta-cell function Randomized, placebo-controlled trial in obese, nondiabetic, insulin-resistant subjects 6 months of 365 mg/day Mg significantly lowered fasting glucose, fasting insulin, insulin resistance and improved insulin sensitivity Three-month supplementation of Mg in subjects with other risk factors (such as mild hypertension or hypomagnesemia) found to improve insulin sensitivity and pancreatic β-cell function Low-Mg diets given to healthy subjects has been shown to impair insulin sensitivity after 3 weeks Experimental evidence from animal studies supports association between Mg and insulin sensitivity: – Animals fed Mg-deficient diets insulin sensitivity of peripheral tissues is reduced via decrease autophosphorylation of tyrosine kinase (a component of the β-subunit of the insulin receptor, which Mg is a cofactor) Hruby A. Diab Care. 2014;37:419-427 Chromium Chromium deficiency may aggravate carbohydrate intolerance Late 1990’s, two randomized, placebo-controlled studies in China found that chromium supplementation had beneficial effects on glycemia Results from small studies indicate that chromium may have a role in: – Glucose intolerance – Gestational diabetes – Corticosteroid-induced diabetes American Diabetes Association stated that benefit from chromium has not been clearly demonstrated, therefore, chromium supplementation in individuals with diabetes or obesity can not be recommended Cefalu WT. Diab Care. 2004;27(11):2741-2751 Dairy Foods 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans: “Moderate evidence…indicates that intake of milk and milk products is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes and with lower blood pressure in adults.” Potential mechanisms of action – Dairy foods are important sources of nutrients: Calcium – increases insulin secretion; is essential for insulin-responsive tissues (i.e., skeletal muscle and adipose tissue) and may reduce insulin resistance Vitamin D – associated with decreased risk of diabetes, possibly by influencing insulin secretion and decreasing insulin resistance Whey protein – reduce body weight gain in animal models Magnesium – associated with reduced diabetes risk (in epidemiologic studies) and with improved insulin sensitivity in some experimental studies but data are limited Fat – trans-palmitoleic acid, a biomarker of dairy fat, was inversely associated with risk of type 2 diabetes, suggests possible protective effect of specific milk-fat components Aune D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1066-1083 Moderate Alcohol Consumption Results of meta-analysis: ~30% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes with moderate alcohol consumption Proposed mechanisms of action with moderate use: – Increased HDL cholesterol – Anti-inflammatory effect – Enhanced insulin sensitivity with lower plasma insulin concentrations Koppes LLJ. Diab Care. 2005;28(3):719-725 Characteristics of a Low-Risk Dietary Pattern Maki KC, et al. AJC. 2004;93(11A):12C-17C. Conclusions Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors for both T2DM and cardiovascular disease that cluster together and are related to insulin resistance. T2DM results from a combination of metabolic defects including insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and liver, pancreatic betacell dysfunction, and excessive adipose tissue lipolysis. Results from intervention trials with weight loss + exercise and a Mediterranean diet intervention, as well as pharmaceutical interventions, show that T2DM can be prevented or delayed in those with pre-diabetes. A diet high in carbohydrate, particularly refined (high GI) carbohydrate, is associated with increased risk for T2DM. Conclusions Substituting foods high in refined carbohydrate with alternatives tends to improve the T2DM/metabolic syndrome risk factor profile Substitutions which show the greatest promise and which warrant further research include: – Carbohydrate-rich foods Low glycemic index High in cereal and fermentable fibers (improved insulin sensitivity) – Protein-rich foods Mainly related to appetite and weight effects – Vegetable (unsaturated) fats – Foods high in polyphenols, fermented dairy products, moderate alcohol in those who drink No more than 14 drinks per week for men and 7 per week for women