Here - Skuuudle

advertisement

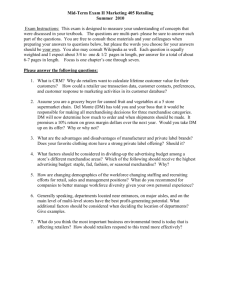

1|Page Price Promises Report 2|Page Executive Summary The following report investigates the current price promises and guarantees offered by retailers in various industries, including supermarkets and technological retailers. In the current climate of economic difficulty and uncertainty, many retailers are introducing seemingly attractive pricing policies to encourage customers to frequent their stores at the expense of their rivals. However, do price guarantees live up to these expectations? Customers often do not have the time or the wherewithal to shop around for the lowest prices and can be swayed by the offer of a ‘lowest price guarantee’ that gains their trust. It is therefore important to understand the reality behind price guarantees in order to protect consumers and prevent against misleading advertisements. It will be seen in this report the stringent conditions of the promises which are hidden behind ambiguous and overreaching advertisements. The report will cover some of the current deals on the market, the lack of consistency that exists within product and price matching, and move towards concluding remarks that point to consumer based research to provide empirical evidence about how consumers, and their behaviour, really respond to price guarantees. 3|Page Introduction Retailers offering price matching policies have long existed but the evolution of competitive intelligence and modern price automation has allowed the technique to become a more robust and reliable measure. However, there is still much controversy surrounding the at times elusive comparisons and highly specific small-print of some price promises that do not stand up to scrutiny. This report aims to look into some of the current price guarantees offered by major retailers in several industries in order to analyse their approaches to the scheme. The report will cover if they open their policy to all competition or only match against certain competitors. In addition, it is important to consider how the promise defines ‘matching’ products; must they be identical or will a near equivalent still be considered as worthy of a price comparison. Within matching, the problem posed by unbranded products must also be addressed. The report will also look into the possibility of misusing price policies. If all retailers adopt price matching or beating philosophies, this can have an adverse affect on competition and leave little incentive for rival firms to drop their prices. Having understood the current position of price promises, the report will point to further research which may be conducted into this area to assess how far shoppers understand and are affected by the clauses attached to a ‘low price guarantee’, as offered by a high proportion of retailers. Further research could also try to understand the impact these guarantees have upon a consumer’s shopping behaviour. With an appreciation of how the customer responds to pricing strategies, some recommendations towards potential improvements to price policies and the specifics behind them could be given. 4|Page The Retailers The table below shows an overview of a brief selection of retailers from various industries such as supermarkets, technology, transport, mobile phones and clothing. As can be seen, the table provides a simple impression of the differences in the price promises on offer in the different markets, which shall now be discussed in further detail. Retailer Asda What does the price promise offer? Which price is compared? Who is the promise aimed against? What is the ‘matching criteria’? Is colour mentioned in the matching criteria? Supported by To be 10% lower Includes price promotions and discounts e.g. half price, within comparable reason Includes price promotions and discounts e.g. half price, within comparable reason Includes price promotions and discounts e.g. half price, within comparable reason Sale prices or discounts included Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Waitrose Identical or like-forlike, based on a set of criteria e.g. flavour or weight Colour not mentioned mysupermark et.com Asda Identical or like-forlike, based on a set of criteria e.g. flavour or weight Colour not mentioned Asda and Tesco Must be identical Colour variations not included Open to all competitors Service conditions are considered, such as delivery charges and guarantee terms Colour not mentioned Tesco Will match the price Sainsbury’s Will match the price John Lewis Will match the price Currys/PC World To be 10% lower Actual price, sales prices or discounts not mentioned Comet, John Lewis, Argos, Staples, Tesco Must be identical Colour not mentioned Comet Will match the price Actual price, sales prices or discounts not mentioned Evan’s Cycles Will match the price Actual price, sale prices or discounts not included Currys, John Lewis, Tesco, Argos and PC world but open to others Open to nearly all competitors Must be identical Colour not mentioned Mothercare Will match the price Open to all competitors Must be identical Colour not mentioned Kiddicare Will match the price Sale prices or discounts not included Actual price, sale prices or discounts not included Open to all competitors Like-for-like Colour not mentioned Carphone Warehouse Will match the price Sale prices or discounts included O2, Orange, TMobile, Vodafone, Virgin Mobile and 3 Must be brand new, same make, model, design and network Colour not mentioned Must be identical Colour variations not included Brandview.co m 5|Page The Deal By looking at the table above it becomes clear that there are two main approaches when deciding on the ‘deal’ offered in a price promise guarantee; to match the lowest price offered by a competitor or to promise to pay 10% below that lowest price. However, for the consumer there are some inconsistencies to understand and obstacles to overcome that are detailed within the small print, tactfully hidden behind enthusiastic advertisements and displays. Firstly, many of the promises require the customer to go online or make a phone call a day or so after their transaction has been made before any benefit can be garnered. Typically, specific information needs to be found and given by the customer which takes up their time and patience. This is sometimes known as the ‘hassle cost’ to the customer. Tesco explain that the delay for their customers is because of the large number of transactions that need to be dealt with and so it takes time for the customer’s order to be found and compared to the other products. With more efficient technology it would be quicker for the comparisons to be made so that customers could be saved from this frustrating process. This would enable the retailer to offer a simpler and more attractive price promise. Sainsbury’s broke this trend by offering the return immediately; the difference in the price of the basket is calculated and offered to the customer in voucher form at the till. As a result of this easy approach to the guarantee the promise was such a success that it was extended until after the Christmas period (The Guardian, 2012) However, as with many other retailers, Sainsbury’s requires that in each transaction at least one of the products brought must be identical to a product offered by Asda or Tesco. The intricacies of comparability and matching will be discussed in further detail later in the report, but from a customer perspective this can be another exasperating aspect of the promise which removes some of the benefit initially expected as a result of the advertising. In a similar way, the Carphone Network’s price promise is substantiated by the claim that “we reserve the right to withdraw this promise or change these terms and conditions at any time” which perhaps serves to foster a customer reaction towards guarantees that the promise is ‘too good to be true’. Particular statements in the small print can make a claim invalid and diminish some of the savings that the customer feels they are rightfully entitled to. While this is not always the case, news articles such as that by the Guardian called ‘why supermarket price promises aren’t all they seem’ 6|Page cause a flurry of activity on social media, such as Twitter, Facebook or through commenting on the site, which shows some of the customer discontent and distrust when facing supermarket promises. A further contradiction of today’s price promises is their popularity amongst retailers. It is seemingly ironic that the three main supermarket retailers (Asda, Tesco and Sainsbury’s) each have their own price matching, or price beating, philosophies against the others. This is a trend that is found in other industries as well, such as with Curry’s and Comet. Such offers, were they to each be fulfilled, would be futile; either causing prices to tumble as each tries to outdo the other or enabling stable prices that remain high. As a result there is no incentive for any competitor to lower their prices as doing so would only lower the profits of them all. However, price promises still may be beneficial to the consumer. A BBC news article from the 9th December shows that 40% purchases are made on special offers. This means that a specific basket of goods brought at a supermarket might be cheaper than a basket of goods brought at another as the basket will be tailored to the offers and savings in each store. For example, a customer may need to buy milk, bread and three other items. From Store A they buy these 5 items as well as 2 unplanned purchases which were on a special deal. If this basket of 7 items was then compared to Store B’s prices for those items it may well be more expensive as Store B does not have the same special offer. As such, customers may be able to save money through these price offers and promises as each supermarket will have special savings that customers are drawn to. Even if this is so, for companies to have a successful price promise, they need an airtight matching philosophy as well as strong data to back it up. Asda’s recent ‘big toy rollback’ successfully rebuffed at least 3 claims made against them due to unfaltering data. It is also important to note that Asda, as with the other retailers, used an independent price comparison company so that the figures were not biased in their favour. This can cause problems for retailers; for example in 2009 an advert which formed part of a Morrisons campaign was forcibly removed by the ASA (Advertising Standards Authority) due to misleading pricing claims that compared their discounted products against the full prices of others. Whilst customers may find some of the refused comparisons unusual, from a technological perspective they are necessary such as differences in ingredients or size. When comments were made to Asda about their comparisons, Asda explained that their comparisons met the ASA standards as over 15,000 of their products were included in the promise. This perhaps shows that, realistically, only a certain level of comparison is possible to be offered to customers. It is therefore important to investigate the matching philosophy which forms the price promises and guarantees. 7|Page The Matching Philosophy The concept of having an unquestionable matching philosophy came about due to the accusations and complaints made by the competition about their rival’s guarantee. In order to ensure the promises stand up to the ASA, don’t impact their own profitability in a negative way and are not taken for granted by opportunistic consumers, each retailer writes their specific standards and clauses attached to the price promise. However, the consumer must be proactive in order to find the standards, which are often published on the retailer’s website. These are often based upon how two products, and their individual features, can be matched as identical or similar and therefore comparable on price. A case in 2006 against Curry’s saw the technology retailer taken to the High Court. The retailer was backed when it became clear that their product, a tumble dryer, came with an air vent that was not included in the cheaper, rival product. As they were not identical, the prices could not be compared and the difference was not paid out to the consumer. As a result of these tests, price promises need to be backed by specific terms that ensure customers do not exploit a loophole or weak aspect of the promise. Asda explicates their promise by saying that “branded products are compared with each other and own label products are only compared where mySupermarket validates the products as being comparable”. This means the branded products can be compared directly but unbranded products can only be compared on a ‘like-for-like’ basis where the products meet the same needs or are intended for the same purpose. Some retailers will match based on sales prices, such as half price but would not include store wide promotions like multi-buy deals, 3 for 2, or buy strawberries get cream free etc as they would be too complicated to match effectively. mySupermarket, who provide the data for Asda, express that they match products based on the following characteristics: Flavour If it’s organic If it’s gluten free If its Fair-trade If it’s free range If it’s low fat If it’s eco-friendly Weight/volume, where there is not more than 10% difference 8|Page They argue that this is done in a way that gives no retailer an artificial advantage. As such, not all products are available to be matched and, as sometimes this is a requirement for the promise to be valid, this can lead to customer dissatisfaction. These specifications can appear to be a way of conning the customer out of their money rather than a necessity for the comparisons to be fair and achievable with the technology available. Tesco use the exact same matching criteria than Asda and so between these two stores Asda should always be 10% cheaper than Tesco when comparing the same basket of goods. Sainsbury’s on the other hand will only compare products that are identical to one another; therefore, the promise does not include their own label brands which would need to be compared ‘like-for-like’. According to their website, the differences in the branded products can include (but are not limited to) pack size, colour, flavour or variety which would mean that products are non-comparable. Here, Sainsbury’s have explicitly mentioned colour in their philosophy. When colour is mentioned in the conditions it is often not included in the price promise as it counts as a ‘variation’ and thus makes the products not identical. Other retailers, such as Curry’s, Comet and Mothercare, do not reveal their actions in regards to colour. This is an interesting point to note as, without a published matching philosophy, colour could be utilised only when it is beneficial to the company. Only expressing that the products must be ‘identical’ leaves room for confusion. Indeed, one definition of ‘identical’ is that two things are “similar or alike in every way” (dictionary.com) which would indicate that colour variations make two products dissimilar and therefore would not allow for price comparisons. Retailers such as Asda and Sainsbury’s have disclosed their philosophies as well as which independent company gathers their data for them and therefore customers would be aware of when their claim is invalid. Asda, Tesco and Sainsbury’s have the most clear and understandable philosophies as their websites dedicate a lot of space to explaining how their products are matched. When Mothercare and Kiddicare, for example, do not specify their like-for-like matching schema it means that colour and other variations could be utilised to enable or disable matches depending on which is most beneficial to them. In order to prevent such activity, it may be to the benefit of the consumer and for the ease of the ASA to introduce the concept of a ‘standard matching philosophy’. This could include all, or a large proportion, of products that are sold by retailers in a variety of industries to define what is a fair price match. For retailers, this would mean that if they promised to be 10% lower than their competition it would be difficult for them to defend their actions through a gray area in their 9|Page conditions in order to evade responsibility. For consumers, they would only need to become familiar with one price matching philosophy, which could remove some of the angst and confusion surrounding the specifics of each retailer’s conditions. Such a matching philosophy could perhaps be created in cooperation with the ASA to ensure that it is to no retailers benefit or detriment. Retailers in the technology sector have a simpler task as products such as laptops or phone will have a MFPN (manufacturer’s part number) that allow products that are identical to be matched more easily. Given this, Curry’s, PC World and Comet stipulate that “the product offered by the competitor's website is exactly the same as the one we sell, and is offered on the same terms”, which would include aspects such as delivery. All three also specify that they must have the product in stock and that they can check and confirm the cheaper price offered by the competitor. Alternatively, Evans Cycles and Mothercare take a slightly different approach. Rather than specifying a few specific competitors against which to price match and remain competitive with, these two retailers (although this practise is not limited to just these two) have a much broader scope and offer the price guarantee against all, or nearly all, of the industry. Mothercare offer to match any price of branded items for all UK retailers including physical stores, catalogues and online retailers as long as the product is branded and sold as new. Similarly, Evan’s Cycles and John Lewis match against nearly all of their competition, citing that the competition need to offer a ‘comparable level of sales and after sales backup to ourselves’, perhaps because of their commitment to offering high quality products and long term guarantees. Evan’s Cycles have one of the widest ranging price promises including a wide range of their main competitors, as well as matching against local specialist competitors in store. Requirements including delivery and support are subjective and could be frustrating to consumers who feel their purchase is accountable under the price promise but are refused due to a judgement that the after sales support is not equal. John Lewis recently came under fire for changing their policy in light of this. It might then be wise to look into the possibility of quantifying after-sales service and other qualitative features rather than discounting their inclusion in price matching. Integrating guarantees or quality of service into the like-for-like process could enable more products to be matched and thus lead to improved customer satisfaction in relation to price promises. 10 | P a g e Closing Remarks This report aims to show the current lack of lucidity of price promises offered by various retailers across industries, especially in the supermarket industry where price wars and competition for customers is fierce. By briefly over-viewing the current deal offered in the guarantees as well as the methodology that backs them, it is possible to see how and why customers feel the promises are disingenuous. Improvements in the data techniques to power price promises could allow for clearer schemes with understandable and clear matching policies that customers could relate to and feel are fair. Additionally, the hassle time of price promises can be frustrating and unnecessary for customers. The efficient utilisation of competitive pricing technology could assist with this time scale. At present, there is often a delay between the purchase and the reward during which time the customer must be proactive in order to receive any benefit. Following suit of retailers like Sainsbury’s in offering an immediate reward has been shown to be successful and appreciated by customers. However, through this technique retailers are able to appear to be actively lowering prices and remaining competitive by introducing a price promise while losing very little in the process. If their rival companies also have price matching schemes in place it enables the industry to charge high prices and provides no incentive to introduce a sale as everyone’s price would decrease (as long as customers were proactive). Research would need to be conducted into the industry to ensure retailers are not implementing unofficial cartels that engender high prices for consumers. Further research into this topic would also be necessary in order to substantiate the ideas put forward in this report. Current findings are based largely upon media output and so real interaction and feedback with customers would be vital in order to find out how consumers truly respond when facing price promises and guarantees. Analysis into this data could reveal if customers change their shopping behaviour as a result of advertised guarantees, such as shopping elsewhere or chasing up retailers when they’ve found the same product for a lower price. Such research could perhaps enable retailers to tailor their price promises to fall in line with popular opinion and thus influence customer behaviour in their favour. 11 | P a g e References BBC News (2011)’ Supermarket Price War: Can they all be the cheapest?’ Available at [http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-16002303] BBC News (2011) Revealed: The truth about supermarket ‘bargains’. Available at: [http://news.bbc.co.uk/panorama/hi/front_page/newsid_9652000/9652944.stm] The Register (2006) Curry’s Price Promise Refusal Backed by High Court. Available at: [http://www.theregister.co.uk/2006/12/19/high_court_backs_currys/ ] The Guardian (2011) Why supermarket price promises aren’t all they seem. Available at: [http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2011/oct/25/supermarket-price-promises-offers?CMP=twt_gu] The Guardian (2012) Sainsbury’s to extend price scheme. Available at: [http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/feedarticle/10035713] Mail Online (2011) Four largest supermarkets could face prosecution for 'misleading shoppers with grocery price war lies.' Available at: [http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2069932/Four-largestsupermarkets-face-prosecution-misleading-shoppers-grocery-price-war-lies.html] Which? (2011) Which tests Asda’s price guarantee. Available [http://www.which.co.uk/news/2011/04/which-tests-asda-price-guarantee-251810/] Dictionary.com (2012) Identical Available at: [http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/identical] at: