TerrestrialBiomes

advertisement

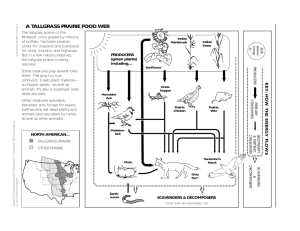

Terrestrial Biomes The largest land community which is convenient to recognize is called a biome. Biomes are characterized by their climax vegetation which is the key to their identification. Major terrestrial biomes include: Tundra, Boreal forest (Taiga, or Northern Coniferous Forest), Temperate Deciduous Forest, Broad-Leafed Evergreen Subtropical Forest, Temperate Grassland, Tropical Savanna, Tropical Rain Forest, Chaparral, and the Desert. The Desert Biome What is a Desert? Deserts in the Southwestern United States are areas of extreme heat and dryness. They occur in regions with less than 10” of rainfall per year, or in regions of greater rainfall if it is unevenly distributed. In some deserts, the amount of evaporation is greater than the amount of rainfall. Typically, desert moisture occurs in brief intervals and is unpredictable from year to year. About one-third of the earth's land mass is arid to semiarid (either desert or semi-desert). There are four major types of deserts: Hot and Dry The seasons are generally warm throughout the year and very hot in the summer. The winters usually bring little rainfall. Temperatures exhibit daily extremes because the atmosphere contains little humidity to block the Sun’s rays. Evaporation rates regularly exceed rainfall rates. Sometimes rain starts falling and evaporates before reaching the ground. Examples are the Sonoran, Mojave and Great Basin deserts of the Southwestern U.S. as well as the Chihuahuan Desert in West Texas and Mexico Semiarid Deserts The major deserts of this type include the sagebrush of Utah, Montana and parts of the Great Basin. They are still hot and dry, but not so much as the above. Scarcity of rainfall may be caused by: 1. A rain shadow of a mountain (Mojave, Sonoran and Great Basin deserts ) 2. Trade wind belts (Sahara desert, world’s largest desert.) 3. Warm land alongside of cold water (coastal deserts) Most deserts receive some rain and have at least a sparse cover of vegetation unless adaphic factors (wind) are particularly unfavorable. Three life forms of plants are adapted to desert conditions: 1. Annuals - avoid drought by growing only when there is adequate moisture (survive as seeds) Bear Poppy Desert Sand Verbena Birdcage Evening Primrose Desert Star 2. Succulents - store water (cacti) Almost the entire stem of a cactus is parenchymatous water storage tissue, thus 80-90 percent of a cactus is water. A cactus plant will lose less than one-thousandth as much water as a mesophytic plant of the same weight. Cacti of arid regions can withstand considerable water loss. For example, a mesophytic plant would wilt or possibly even die when it loses 10-20 percent of its water. Cacti can withstand a water loss of 60 percent. Cactus stomates are open at night and store carbon dioxide until the daytime so it can photosynthesize. The storing of carbon dioxide from night to day is a special feature of succulent plants called "succulent metabolism” or technically as CAM metabolism. 3. Desert shrubs Desert shrubs have extensive roots and small, thick waxy leaves to reduce transpiration. The leaves may be shed in prolonged dry seasons. Bark may have chlorophyll. The extensive root systems are adapted to absorb water very quickly. Color, hairs and spines, salt glands, shape, size, and growth form are some of the ways that plants deal with excess thermal energy. The color of a plant affects the amount of solar radiation absorbed by leaves. Leaves that are shiny, light green or gray/silver in color have a high reflectivity and absorb less heat. Many desert shrubs use color to stay cool. The Great Basin Desert, a rain shadow desert, is the largest U. S. desert. It covers an arid expanse of about 190,000 square miles and is bordered by the Sierra Nevada Range on the west and the Rocky Mountains on the east, the Columbia Plateau to the north and the Mojave and Sonoran deserts to the south. Sagebrush is the most common plant in the Great basin Great Basin Desert Sagebrush Desert animals are also adapted Reptiles and insects are somewhat “pre-adapted” because of their relatively impervious integument and dry excretions. As a group, mammals are not well adapted because they excrete urea that requires water for excretion, and most use water for temperature regulation. However many mammals managed to adapt to the dry conditions. Kangaroo rats and pocket gophers do not have to drink water and can live on a diet of dry seeds. They conserve metabolic water by excreting a concentrated urine and do not use water for temperature regulation. They remain in their burrows during the day. Other adaptations include means of dissipating body heat other than evaporative cooling such as subsurface blood flow (large ears of hare with rich blood supply). Chaparral Biomes Chaparral Biomes occur in regions with abundant winter rainfall but with dry summers. The climax vegetation consists of trees or shrubs with hard thick evergreen leaves. Chaparral communities are extensive in California and Mexico. A large number of plant species may serve as dominants depending on the region and local conditions. Fire is an important factor that tends to perpetuate shrub dominance. In California, 5-6 million acres of slopes and canyons are covered with chaparral shrubs which form dense thickets. The rainy season usually extends from November to May. Mule deer and many birds inhabit the chaparral during this period, then move to higher altitudes during the hot summer. Animals are all mainly grassland and desert types adapted to hot, dry weather. A few examples: coyotes, jack rabbits, mule deer, lizards, snakes, chipmunks, wood rats, bush rabbits. Temperate Grassland Biome Grasslands occur where rainfall is too low to support a forest but higher than that of a desert (10 - 30” per Yr). However, grasslands also occur in areas of forest climate when edaphic factors (fire) favor grass. Temperate grasslands usually occur in the interior of continents. They are important economically because they provide natural pastures for grazing, and conversion of moist grasslands into cultured grain crops involves very little basic change in ecosystem structure. Grasslands in drier climates such as found in the Western Great Plains consist of shorter grasses than those in the Eastern Great Plains (tall grasslands). Great Plains, mixed tall and short grassland Most grassland mammals are either running or burrowing types. Aggregation into colonies or herds is characteristic. Burrowers include ground squirrels, gophers, and prairie dogs. Burrowing predators like burrowing owls and the black footed ferret (an endangered species) prey on the rodents. Typical birds are prairie chickens, meadow larks and hawks. The Blackland Prairie totals about 4.3 million hectares or roughly six percent of the total land area of Texas and is a region slightly larger than the state of Maryland. It coincides almost exactly with a belt of outcropping Upper Cretaceous marine limestone and shales that upon weathering forms the characteristic black, calcareous, alkaline, heavy clay, "black waxy" soil (Diggs et al. 1999). The Blackland Prairie Conditions in presettlement Blackland Prairies were strikingly different from those found today and the most striking difference was the presence of vast expanses of tall grass prairie (Diggs et al. 1999). Fire was an important factor in maintenance of the original prairie vegetation and had a major impact on community structure (Diggs et al. 1999). The Blackland Prairie Tall grass prairie fires would have been stopped only by the lack of dry fuel or by a major waterway. Even waterway vegetation was susceptible during dry years and trees were rare even along some stream banks (Diggs et al. 1999) (For other citations, see the literature cited section from Diggs et al. 1999 at: http://artemis.austincollege.edu/acad/bio/gdi ggs/literature.html The Blackland Prairie early (back to the 1830s) surveyor records of mesquite as the most common tree in presettlement upland prairies in Navarro County suggest ". . .the legendary spread of mesquite into North Texas by longhorn cattle may be an errant concept" (Jurney 1987). Roemer's (1849) mention of "extensive prairies covered with mesquite trees" also points to mesquite as a natural component of the vegetation. The Blackland Prairie mesquite has increased in many areas and the observations mentioned above are not so early as to preclude mesquite having already being spread to some extent by land use changes (Diggs et al. 1999). While some question the degree to which mesquite was spread by longhorns, animals have had profound impacts on the vegetation since long before settlement (Diggs et al. 1999). The Blackland Prairie These range from dust bathing and mating displays by bison to damming and herbivory by beaver to the more subtle roles of pollination and seed dispersal. Present animal life is different and some species reduced compared with earlier times. In addition to present-day species such as the white-tailed deer, coyote, fox, and bobcat, a number of other large or species occurred (Diggs et al. 1999). The Blackland Prairie Brooke (1848) writing of Grayson County, said black bears were quite common ("I. . have never tasted any meat I like better.") as were deer; mountain lions and wolves. Another predator, the ocelot, is thought to have ranged as far north as the Red River (Hall & Kelson 1959). Strecker (1924), for example, reported that ocelot occurred in the bottoms of the Brazos River near Waco The Blackland Prairie Even jaguar are believed to have ranged north to the Red River; the last jaguar record from North Central Texas was a large male killed in Mills County (Lampasas Cut Plain) in 1903 (Bailey 1905). The collared peccary or javelina, was also originally present in the southern portion of the area, north to at least the Brazos River valley in McLennan County near Waco (Davis & Schmidly 1994). The Blackland Prairie Other large mammals that previously occurred in appropriate habitats of the Blackland Prairie as well as throughout the rest of North Central Texas include river otter, ringtail, and badger (Davis & Schmidly 1994). Pronghorn antelope were also native. Smythe (1852) saw a herd on the E edge of the Blacklands while Roemer (1849) saw them where the Blackland Prairie and Lampasas Cut Plain intersect. The Blackland Prairie While not native, wild horses, introduced from the Spanish, were by the early 1800s extremely common in Texas and were probably having a significant impact on the vegetation. (Diggs et al. 1999). Brooke (1848), writing about early Grayson County, mentioned both turkeys and prairie chickens. The Blackland Prairie The extinct passenger pigeon is also well documented for the Blackland Prairie and the ivory-billed woodpecker species, was also present in bottomland forests in the Blacklands. Another extinct species, the Carolina parakeet was probably present in the bottomland forests of the Blackland Prairie ((Diggs et al. 1999). The Blackland Prairie Alligators were abundant in places, with Kendall (1845) reporting them along the San Gabriel in the southern Blackland Prairie. He also stated that, "The stream abounds with trout, perch, and catfish, as do nearly all the watercourses in this section of Texas." Alligators occurred in appropriate habitats throughout most of the Blackland Prairie (Brown 1950; Hibbard 1960; Dixon 1987). The Blackland Prairie According to Gould and Shaw (1983), the Blackland Prairie (and in fact all of North Central Texas) is part of the True Prairie grassland association, extending from Texas to southern Manitoba. Two of the common dominants of the prairie included little bluestem and Indian grass along with numerous other grass species and forbs. The Blackland Prairie Although prairie dominated, some wooded areas were present at the time of settlement. Examples include bottomland forests and wooded ravines along the larger waterways, mottes in protected areas or on certain soils, scarp woodlands at contact zones with the Edwards Plateau and Lampasas Cut Plain, and upland oak woodlands similar to the Cross Timbers (Gehlbach 1988; Nixon et al. 1990; Diamond & Smeins 1993). The Blackland Prairie Oaks, elms, ash, sugarberry were common trees with many kinds of shrubs. With the exception of preserves, small remnants, or native hay meadows, almost nothing remains of the original Blackland Prairie communities. According to Diamond et al. (1987), all of the tall grass community types are ". . .endangered or threatened, primarily due to conversion of these types to row crops." The Blackland Prairie Recurrent fire and grazing by bison were natural processes that maintained the Blackland ecosystem; the removal of these processes is a disturbance that causes changes in the vegetation (Smeins 1984; Smeins & Diamond 1986; Diamond & Smeins 1993). The Blackland Prairie Periodic disturbance is essential for the maintenance of prairie. However, even native hay meadows, which are routinely disturbed, are often very different from the original due to substitution of mowing and herbicide use in place of fire and grazing. The results include a reduction in broad-leaved plants and an increased abundance of grasses (Diamond & Smeins 1993). The Blackland Prairie While grazing was a natural component of the Blacklands and many other Texas ecosystems, overstocking and thus overgrazing by domesticated animals has also caused a dramatic decline and even near elimination of numerous plants from many areas (Cory 1949). The cumulative effect of all these human-induced changes is that the Blackland Prairie communities have been largely destroyed (Diggs et al. 1999). The Blackland Prairie Large areas that were once tall grass prairie are now covered by crops or other introduced and now naturalized species such as King Ranch bluestem, Bermuda grass, and Johnson grass. Roadsides and pastures are particularly obvious examples; in many cases hardly any native grasses can be found. In these areas there has also been an accompanying dramatic reduction in native forb diversity (Diggs et al. 1999). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES Vegetationally, it is quite diverse and includes the East and West Cross Timbers, the Fort Worth Prairie, and the Lampasas Cut Plain. Cross Timbers stretch from Texas north through Oklahoma to Kansas (Marriott 1943; Dyksterhuis 1948; Kuchler 1974), and are found in Texas from the Red River south for about 150 miles. CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES They are actually two discrete belts of forest divided by the enclosed Grand Prairie (Dyksterhuis 1948). Surrounded by prairie on both sides (Blackland Prairie to the east, Rolling Plains to the west), they represent a final disjunct western extension of eastern deciduous forest before the vegetation changes into the vast expanse of central U.S. grasslands known as the Great Plains (Diggs et al. 1999). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES The two separate belts are the East Cross Timbers and the West Cross Timbers, sometimes referred to as the Lower Cross Timbers and Upper Cross Timbers respectively (Diggs et al. 1999). According to Hill (1887), these names developed because the West or Upper Cross Timbers is at a greater altitude and in a more upstream position relative to the flow of rivers in the area. CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES The East Cross Timbers is a narrow strip (roughly along the 97th meridian) extending from the Red River, in eastern Cooke and western Grayson counties, south to near Waco where it merges with the riverine forests of the Brazos River (Hayward & Yelderman 1991). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES The somewhat wider West Cross Timbers stretches west from the Grand Prairie, which includes the Ft. Worth Prairie and Lampasas Cut Plain to the beginning of the Rolling Plains and includes the rather rugged Palo Pinto Country (in Eastland, Jack, Palo Pinto, Stephens, and Young counties) (Diggs et al. 1999). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES The Fort Worth Prairie portion of the Grand Prairie extends as a continuous body of open grasslands, from near the Red River in the north, south to where it ends in the wooded area along the Brazos River near the Johnson County-Hill County line (Dyksterhuis 1946). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES The Lampasas Cut Plain, the largest portion of the Grand Prairie, is highly dissected butte and mesa country with extensive lowlands, and can in some ways be considered a northernextension of the Texas Hill Country and Edwards Plateau. It has strong geologic and floristic links with the Edwards Plateau and is considered a part of the Edwards Plateau by some authorities (e.g., Riskind & Diamond 1988). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES The Cross Timbers vegetation at the time of contact by Europeans thus probably exhibited considerable variation (Diggs et al. 1999). Parker (1856) described the area just west of the East Cross Timbers but east of what he referred to as the Grand Prairie (east of Gainesville in Cooke County) as follows: . . . soon leaving the timber, we entered upon a broken country, consisting of ridges of sand and limestone, interspersed with small prairies and small strips of timber, principally black jack, until we emerged upon and crossed Elm Fork of the Trinity, where, on account of the intense heat, Captain Marcy determined to halt and encamp, thereafter, intending to march by moonlight, until we reached the Grand Prairie (Parker 1856) . The variable nature of the Cross Timbers is also reflected in the following description from Kendall (1845): The growth of timber is principally small, gnarled, post oaks and black jacks, and in many places the traveler will find an almost impenetrable undergrowth of brier and other thorny bushes. Here and there he will also find a small valley where timber is large and the land rich and fertile, and occasionally a small prairie intervenes; but the general face of the country is broken and hilly, and the soil thin. CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES The animal life of the Cross Timbers was probably similar to that described earlier for the Blackland Prairie. The East and West cross timbers, have their woody overstory consisting primarily of post oak and blackjack oak (Diggs et al. 1999). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES Based on these accounts and on an extensive vegetational study of the West Cross Timbers by Dyksterhuis (1948), presettlement vegetation can probably best be described as a savannah with an oak overstory, but dominated little bluestem, with two other grasses, big bluestem, and Indian grass, as lesser dominants. Little bluestem CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES At present, in many Cross Timbers localities, younger trees are often branched to the ground, making movement through the vegetation extremely difficult and denying habitat for the originally dominant grasses; dense cedar brakes (Diggs et al. 1999), mesquite and prickly pear are problematic, likely due to fire suppression and overgrazing. CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES One of the most striking features of the Cross Timbers is that this vegetational area contains significant remnants of virgin forests (Stahle & Hehr 1984; Stahle et al. 1985). According to Stahle (1996a), “. . . literally thousands of ancient post oakblackjack oak forests still enhance the landscapes and biodiversity of. . . the Cross Timbers along the eastern margin of the southern Great Plains. . . .” CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES As as result, this is one of the largest relatively unaltered forest vegetation types in the eastern United States (Stahle & Hehr 1984). The small stature and often poor growth form of post and blackjack oaks made these species commercially unattractive and therefore less subject to systematic logging than other more productive forest types (Diggs et al. 1999). CROSS TIMBERS AND PRAIRIES Riparian regions in both the Cross Timbers and Grand Prairie regions have high biodiversity Major rivers include the Red, Trinity, Brazos, and the Colorado Handout on the Colorado River and the Lampasas Cut Plain Tropical Savanna Biome (Tropical Grasslands) Tropical savannas are found in warm regions with 40 - 60 inches of rainfall per year, but with a prolonged dry season when fires are an important part of the environment. Tropical savannas consist of grasslands with scattered clumps of trees. The largest savanna is in Africa occupying 1/3 of the area of Southern Africa, but others occur in South America and Australia. Diversity of flora is not great. The diversity and abundance of hoofed animals in the African savanna is unequaled any where else in the world. Antelope, wildebeest, zebra, and giraffe graze, and are sought by lions and other predators. Termites are especially abundant in the tropical savannas of the world, and their tall termitarias are conspicuous elements of the savanna landscape Temperate Deciduous Forest Biome Occupy areas of abundant, evenly distributed rainfall (30-60˝ per year) and moderate temperatures that exhibit seasonal patterns. Characterized by trees that loose their leaves in the winter=deciduous. Found in eastern N. America, Europe, parts of Japan, Australia, and the tip of S. America. Many plants produce pulpy fruits and nuts. The soil is fertile. In fact, some of the great agricultural regions are found in this biome. That is one of the reasons there are not many original deciduous forests left in the world. Almost all of the forests in North America are second growth forests but it still has the biggest variety of original plant species. In Europe there are only a few species of original trees left. Most of the forests have been cleared for agriculture. A few common animals found in the deciduous forest are, deer, bear, gray squirrels, mice, raccoons, bobcats, wild turkey, salamanders, snakes, frogs and many types of insects. Broad-Leafed Evergreen Subtropical Forest Biome Subtropical areas where moisture remains high and temperature differences are not pronounced. The temperate deciduous forest gives way to the broadleaf evergreen forest climax. This community is well developed in the warm temperate marine climate of central and southern Japan, and the subtropical regions of N. America, along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, the Caribbean, Florida Everglades and Keys. Characterized by live oaks, magnolias, palms. Oaks and other trees may support epiphytes (Spanish moss) and lichens. Animals similar to deciduous forest biome. Tropical Rain Forest Biome The variety of life reaches its peak in the broad-leafed evergreen tropical rain forest which occupies low altitude zones near the equator. Rainfall exceeds 80- 90˝ per year with one or more dry seasons (5˝ per month or less). Rain forests occur in three main areas: 1. The Amazon (South America) and the Central American Isthmus 2. The Congo-Niger & Zambezi basins of central Africa and Madagascar. 3. The Indo-Malay-Borneo-New Guinea regions of SE Asia & Australia They differ in species present since they occupy different biogeographical regions but the forest structure and ecology is similar in all three regions. The rain forest is highly stratified. Trees generally form three layers resulting in the stratification of animal life. 1. Emergents - Scattered very tall trees projecting above the canopy (forest giants). They house many birds and insects. 2. Canopy - An evergreen carpet 80-100 ft tall. This leafy environment is full of life. It includes: insects, birds, reptiles, mammals, and more. 3. Understory - Consisting of short, broad-leafed plants, vines, and seedlings. It becomes dense only where there is a break in the canopy. 4. Forest Floor - Consisting of forest litter in various stages of decomposition. The floor is rich with animal life, especially insects. The largest animals in the rainforest generally live here Diversity reaches its peak in the rain forest. A much larger proportion of animals lives in the upper layer of the vegetation than in temperate forests where most animal life is near ground level. Rain forests are rich in abundance of arboreal mammals, reptiles like chameleons, geckos, iguanas, snakes as well as many birds. Fruit and termites are staple foods. More than half of the different kinds animals and plants in the world live in the tropical rain forests. The abundant sunlight, warm temperatures, and daily rain lead to a fast turnover of nutrients, and plant growth is rapid. More than half of the different kinds animals and plants in the world live in the tropical rain forests. Looking at the plant life, it is easy to think that the soil is rich, but it is actually nutrient poor. Northern Coniferous Forest (Taiga) (Boreal Forest) Biome This is the largest biome. It is found in the northern hemisphere close to the polar region. This cold biome stretches across the northern portions of North America, Europe, and Asia. Large population centers, such as Moscow and Toronto, can be found in the southern portion of this biome, but the northern portion is relatively unpopulated. The biome is also called the Boreal Forest or Taiga (Russian for “land of little sticks”). Identifying life forms include needle-leafed evergreen tree (spruces, firs, pines). Boreal forests are among the great lumberproducing regions of the world. Compared to the arctic tundra, the climate of the boreal forest is characterized by a longer and warmer growing season. Precipitation averages 20 inches per year, but ranges from 40 inches in the eastern regions to 10 inches in interior of Alaska. Animals such as moose, snowshoe hare and grouse are dependent, in part, on broad-leafed developmental communities. Tundra Biome The Arctic tundra is found across northern Alaska, Canada, and Siberia. This biome has long cold winters and short cool summers. The Arctic tundra has low precipitation (less than 10 inches per year) and dry winds. These conditions make the Arctic tundra a desertlike climate. The word “tundra” means “a treeless plain”. At lower latitudes, a similar landscape is found on the peaks of tall mountains (alpine tundra). Chief limiting factors are low temperatures and short growing seasons Ground remains frozen except for the upper few inches during the short (60-day) growing season. (Permafrost is permanently frozen) Major herbivores of the tundra include waterfowl, ptarmigan, lemmings, hares, musk ox, caribou. In some parts of the tundra, lemmings are the dominant herbivore. A major carnivore is the Arctic fox. Lemmings: Lemming suicide is fiction. Contrary to popular belief, lemmings do not periodically hurl themselves off of cliffs and into the sea. Cyclical explosions in population do occasionally induce lemmings to attempt to migrate to areas of lesser population density. When such a migration occurs, some lemmings die by falling over cliffs or drowning in lakes or rivers. These deaths are not deliberate "suicide" attempts, however, but accidental deaths resulting from the lemmings' venturing into unfamiliar territories and being crowded and pushed over dangerous ledges. In fact, when the competition for food, space, or mates becomes too intense, lemmings are much more likely to kill each other than to kill themselves. Vegetation - The number of plant species on the tundra is few, and their growth is low, with most of the biomass concentrated in the roots. The growing season is short, and plants are more likely to reproduce asexually by division than sexually by flower pollination. Typical arctic vegetation consists of cotton sedge and dwarf woody plants like willows with associated mosses and lichens. These plant communities are adapted to sweeping winds. They carry on photosynthesis at low temperatures, low light intensities, and long periods of daylight. Plant communities of the alpine tundra consist of matmaking and cushion-forming plants. These plants are rare in the Arctic. They are adapted to gusting winds, heavy snows, and widely ranging temperatures. They carry on photosynthesis under brilliant light in short periods of daylight. cotton sedge cushion plants Cushion plants grow in a low, tight clumps and look like small cushions. Cushion plants are more common in the alpine tundra where their growth form helps protect them from the cold.