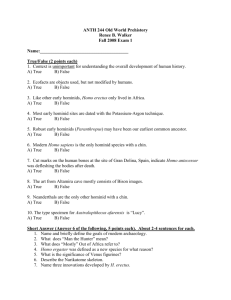

ANG 6930

Proseminar in

Anthropology IIA:

Bioanthropology

Day 5

ANG 6930

Prof. Connie J. Mulligan

Department of Anthropology

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

This week

•

Hominoid to hominin

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Dating the ape-human split

Australopiths

Early hominin subsistence and social organization

Origins of genus Homo

Homo erectus

Neanderthals and other archaic humans

Reading

–

The Human Species, Chpts 9 (Primate origins and evolution), 10

(Beginnings of human evolution), 11 (Origin/evolution of genus Homo)

–

Course packet

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

“A new kind of ancestor: Ardipithecus unveiled”, Science, 326:36-40.

“Candidate human ancestor from South Africa sparks praise and debate”, Science

Klein RG. 2009. Darwin and the recent African origin of modern humans. PNAS 106:1600716009.

“New statistical model moves human evolution back three million years” ScienceDaily,

11/9/2010.

Teaford MR and Ungar PS. 2000. Diet and the evolution of the earliest human ancestors.

PNAS 97:13506-13511.

Conroy GC. 2002. Speciosity in the early Homo lineage: Too many, too few, or just about

right? Journal of Human Evolution 43:759-766.

Premo LS and Hublin J-J. 2009. Culture, population structure, and low genetic diversity in

Pleistocene hominins. PNAS 106:33-37.

Hublin JJ. 2009. The origin of Neanderthals. PNAS 106:16022-16027.

“Tales of a prehistoric human genome” Science 2009, 323:866-871.

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

Optional– Noonan JP. Neanderthal genomics and the evolution of modern humans.

All rights reserved

Next week

•

•

Origin of modern humans/Human biodiversity and race

•

•

•

•

•

Homo floresiensis

Anatomically modern Homo sapiens

African replacement or multiregional evolution?

Global patterns of human genetic variation

Anthropological critique of race

Reading

–

–

The Human Species, Chpts 12 (Origin of modern humans), 13 (Human

variation), 14 (Genetics, history and ancestry)

Course packet

•

•

•

•

•

•

Tattersall I. 2009. Human origins: Out of Africa. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences 106:16018-16021.

Powledge TM. 2006. What is the Hobbit? PLoS Biology. 4:2186-2189.

Scheinfeldt L et al. 2010. Working toward a synthesis of archaeological,

linguistic, and genetic data for inferring African population history.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107:8931-8938.

Serre D and Pääbo S. 2004. Evidence for gradients of human genetic diversity

within and among continents. Genome Research 14:1679-1685.

Haak W. 2008. Ancient DNA, strontium isotopes, and osteological analyses

shed light on social and kinship organization of the Later Stone Age. PNAS.

105:18226-18231.

“On the origin of art and symbolism” Science 2009, 323:709-711. Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Hominoid to Hominin

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Overview

• Origin of hominins in late Miocene

– Ardipithecus

– Orrorin

– Sahelanthropus

• Plio-pleistocene hominin adaptive radiation

– Australopithecus

– Paranthropus

– Kenyanthropus

• Hominin phylogenies

• Evolution of bipedalism

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Overview of hominid evolution

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Climate change in late Miocene/Pliocene

Hominids evolved ~6 mill yrs ago

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Late Miocene to Early Pliocene

• Apes flourished in Miocene, but most genera became

extinct

• Falling temperatures changed climate in African tropics

– Rain fall declined, became more seasonal

– Tropical forests shrank; woodlands, grasslands expanded

• Ecological pressures led to evolution of first hominids

about 6-8 mya

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

What makes a hominid?

• Human uniqueness long defined in terms of

brain evolution

• Now clear that bipedalism predates big brains

by several million years

• Bipedalism associated with morphological

changes

• Dietary changes associated with new habitats,

also reflected in different chewing apparatus

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Shared, derived traits of hominids

• Habitual bipedalism

• Chewing apparatus

–

–

–

–

Wide parabolic dental arcade

Thick enamel

Reduced canines

Larger molars in relation to other teeth

• Much larger brains relative to body size

• Slow development with long juvenile period

• Elaborate, highly variable material and symbolic

culture, transmitted in part through spoken language

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Major discoveries of hominids

Mainly South Africa and East Africa

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

New discoveries of hominids 5-7 mya

• (Ardipithecus ramidus

– 1992

– Middle Awash in Ethiopia

– Previously thought to be older than 5

mya, now 4.4 mya)

• Orrorin tugenensis

– 2001

– Tugen Hills in Kenya

• Sahelanthropus tchadensis

– 2002

– Toros-Menalla in Chad

• Ardipithecus kadabba

– 2004

– Middle Awash in Ethiopia

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Sahelanthropus

tchadensis

• Discovered in 2002 by Michel

Brunet and colleagues

• New dental and mandibular

specimens reported in 2005

• Estimated 6-7 mya in Chad, not

securely dated

– Fits with humans if older humanchimp divergence is used

• Unique mix of humanlike and

apelike features

– Relatively flat face and massive

brow ridge

– Small brain, primitive teeth, back

of skull very apelike

• No postcranial fossils known

• Could be hominoid, not hominid

Toumaï

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Orrorin tugenensis

• Announced in 2001 by Senut

and Pickford

• 6 mya at Tugen Hills in

Kenya

• No cranial fossils recovered

– Keep controversy alive (could be

ardipithecus)

• Mixture of apelike-humanlike

– Incisors, canines, premolars,

arm and fingers like

chimpanzees

– Thick enamel, femur humanlike

• Bipedalism inferred from

femur anatomy

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Ardipithecus kadabba

• 1st designated as

subspecies, then promoted

to full species in 2004

• Even older - 5.8 – 5.2 Ma

• Ethiopia (Middle Awash)

• Similar to Sahelanthropus in

mix of features

• Slightly smaller Canine

• Wooded habitat

Yohannes Haile-Selassie

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Ardipithecus ramidus

First identified and named in 1994 – thought to be older than 5 mya

15 years to excavate >100 fragments and reassemble them, e.g.

>1000 hours on skull (Gen Suwa) – 4.4 mya

Nature 371: 306-312 (1994)

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Ardipithecus ramidus – “ARDI”

• 4.4 mya

• Discovered in Middle Awash

– Aramis (Ethiopia)

• Most complete skeleton

older than Lucy

• Not Homo and not

Australopithecus

• Similarities to

Sahelanthropus

– Very early stage of human

evolution

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Unexpected anatomy

White, Gibbons (2009) A new kind of ancestor: Ardipithecus unveiled.

Science

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

White, Gibbons (2009) A new kind of ancestor: Ardipithecus unveiled.

Science

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Significance of late Miocene hominids

• Pushes back fossil record of hominids by 2-3

million years

– Until early 1990s, earliest hominids were < 4 mya

– Now appears that multiple, diverse hominids

may date to late Miocene

• Forces rethinking of bipedalism

– Early hominids appear to have inhabited

forested environments, not open savannas

– Challenges some scenarios for adaptive value of

bipedalism

• Having hand free to use tools doesn’t seem important

Copyright 2011

since bipedalism predates tool use by 3.5 my Mulligan,

All rights reserved

Diversification of hominids

• Hominid lineage proliferated 4–2 mya, likely

with multiple species living in Africa at a

time

• Taxonomic classification of

these hominids hotly contested

– Lumpers and splitters

– Linear and bushy family trees

• Bernard Wood and Mark Collard advocate

three genera

– Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Kenyanthropus

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Australopithecus

• Debate about how many species belong to genus

• Two major points of disagreement

– Robust australopithecines

– Early Homo

• Wood and Collard’s scheme narrows definition of

Australopithecus and of Homo

• Taxonomic debates reflect limitations of data,

philosophical differences, and politics

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Primitive and later hominids

• Primitive hominids

– Australopithecus anamensis

– Australopithecus afarensis

– Kenyanthropus platyops

• Later hominids

– Paranthropus or robust Australopithecus

– Australopithecus africanus

– Australopithecus garhi

– Australopithecus habilis, A. rudolfensis

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Australopithecus anamensis

• Earliest species of genus to be found

• Dated to 4.2-3.8 mya near Lake

Turkana in Kenya (Leakey et al. 1995, 1998)

• Bipedalism inferred from knee and

ankle joints

– Thick enamel and smaller canines

– Arm bone suggests primitive arboreal

adaptations

– Dental arcade and chin chimpanzeelike

• Primitive characters suggest A.

anamensis may be ancestral to later

australopithecines

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Australopithecus afarensis

• Most well-known

australopithecine = Lucy

– Most complete skeleton (40%)

• Dates to 3.5-2.3 mya in East Africa

(Don Johanson, 1970s)

• Bipedalism

– Shape of pelvis, femur, foot, Laetoli

footprints

– May not have been fully modern gait

• Derived characters intermediate

between humans and chimps

– Dental arcade

– Canines

– Premolar cusps

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Laetoli footprints

• Formed and preserved by a chance

combination of events -- a volcanic

eruption, a rainstorm, and another

ashfall

– Tanzania

• Two individuals, possibly three

– Fainter of two clear trails is unbalanced,

individual possibly burdened on one

side w/ an infant?

• A. afarensis

– No other hominid near this age, 3.6 mya

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Kenyanthropus platyops

• Dated to 3.5-3.2 mya on

western side of Lake

Turkana (Leakey et al. 2001)

• Mosaic of features

– Small ear hole (like early

Australopithecus)

– Thick enamel (like later

Australopithecus)

– Relatively flat face (like later

hominids)

– Apart from brain size, is similar

to Homo rudolfensis

KNM-WT 40000

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Robust hominids

• Robust early hominids have

crania and teeth specialized

for heavy chewing

– Sagittal crest

– Flared zygomatic arches

– Massive mandibles and molars

• Debate over proper genus

(Australopithecus or Paranthropus)

– Paranthropus aethiopicus

– Paranthropus robustus

– Paranthropus boisei

KNM-ER 17000

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Who became Homo?

• General agreement that the robust

australopithecines became extinct ~1 mya

and did not give rise to modern humans

• Who did?

– Three major candidates

• Australopithecus africanus

• Australopithecus garhi

• Australopithecus sebida

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Australopithecus africanus

• First known australopithecine

(Dart 1925)

• Dated to 3-2.2 mya in South

Africa

• More apelike physique than A.

afarensis

– Arms longer than legs – arboreality

– Some adaptations for heavy

chewing

• Probably like other australopiths,

matured rapidly like chimpanzees

• One candidate for immediate

ancestor to Homo

Taung Child Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Australopithecus garhi

• Dated to around 2.5 mya in

East Africa (Asfaw et al. 1999)

• Small brains like A. afarensis

and A. africanus

• Very prognathic face, larger

teeth, sagittal crest

• Some evidence that made

stone tools and used to cut

meat from bones, extract

marrow

• Other candidate for immediate

ancestor to Homo

BOU-VP-12/130

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Known dates for hominid species

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Hominid phylogenies

Gibbons, Ann. 2002. "In Search of the First Hominids." Science 295:1214-1219.

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Science online extras

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Hominid to Homo

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Genus Homo

• Increased brain size

• Reduction in size of face and teeth

• Increased reliance on cultural adaptations

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Evolution of brain size

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Brain size in fossil hominids

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Proposed species of Homo

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Homo erectus

• “upright walking human”

• Appeared in Africa 1.7-1.8 mya

– Possibly as young as 50kya = co-existence w/ moderns

• First hominid to migrate out of Africa into

temperate parts of Eurasia 1.8 Ma – 500 kya

• Primitive cranial traits include large brow ridges,

postorbital constriction, flat cranial vault

• Derived traits include less prognathism, higher

skull vault, smaller teeth, larger brain, modern

limb proportions

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

H. erectus/ergaster sites

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

KNM-WT 15000

• Most complete H erectus

skeleton

• “Turkana boy”

• ~ 12 years of age

• Evidence of modern limb

proportions

• Tall

• Large brain

• Appears to be juvenile,

not adolescent

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Origins of stone tools

• Earliest evidence for intentionally modified

stone tools is 2.5 mya in East Africa

• Earliest stone tools in South Africa ~ 2 mya

• Bone tools appear 2-1 mya at Olduvai Gorge

(Tanzania) and in South Africa

• Oldowan tool technology

– H habilis and H rudolfensis

• Acheulean tool technology

– H erectus

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Oldowan tool industry

• Mode 1 technology

• Simple tools made

from rounded stones,

flaked to produce

sharp edge

• Variable form

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Importance of Oldowan hominids

• Plausible candidates for link between early

apelike hominids and later hominids

• Studying Oldowan archaeological sites

yields insight in processes shaping human

evolution

• Combining archaeology, ethnography, and

biological anthropology informs

understanding of transition to modern

humans

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Oldowan hominids relied on

hunting and extractive foraging

• Kathy Schick and Nicholas

Toth (Indiana)

• Experimental studies of

Oldowan tool use

• Flakes, not cores, may be

most important tools

• Useful for many functions,

including butchering

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Bone tools used to dig up bulbs, tubers,

excavate termite mounds

Swartkrans

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Archaeological evidence for meat eating

• Oldowan sites at Olduvai Gorge littered with

fossilized animal bone from many species

• Taphonomic studies suggest most fossils not

accumulated by natural processes

• Taphonomic studies also show evidence that

Oldowan hominids processed carcasses

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Taphonomy shows hominids used

Oldowan tools to process carcasses

Cut marks made by carnivore teeth

Cut marks made by stone tools

Electron micrographs of 1.8 mya fossil bones from Olduvai Gorge

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Hunters or scavengers?

• Controversy over whether Oldowan

hominids were hunters or scavengers

• Comparative perspective

– Most large mammalian carnivores practice both

hunting and scavening

– No mammalian carnivore subsists entirely by

scavenging

• Taphonomic studies provide evidence of

both hunting and scavenging

– Cut marks on meaty limb bones not usually left

to scavengers

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Types of Food Resources

• Collected foods are simply collected and

eaten (e.g., ripe fruit or leaves)

• Extracted foods must be processed (e.g.,

fruits in hard shells, tubers, or termites)

• Hunted foods must be caught or trapped

(e.g., vertebrate prey)

Vary in amount of knowledge and skill

required to obtain

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Chimpanzee and Human Foraging

Patterns

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Contemporary foraging patterns

• Contemporary human foragers get most

calories from extracted or hunted resources

• Provide high nutritional quality, but require

difficult and time-consuming skills

– Aché men reach peak hunting efficiency at age 35

– Hadza women achieve maximum efficiency in root

acquisition at 35-40 years old

• Shapes human life history and division of labor

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Hunting and foraging favors food

sharing and division of labor

• In contemporary foragers,

extensive food sharing and

sexual division of labor

• Division of labor

– Difficult skills require time to learn

– Child care more compatible with

gathering

• Meat eating favors food sharing

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Sexual division of labor in

contemporary foragers

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Neanderthals

• Neander Valley

• H sapiens neanderthalensis or

H neanderthalensis

– Closest to modern humans other

than Cro Magnon

• Lived throughout Europe and

the Middle East, 150-28 kya

– Overlapped with modern humans

in space and time

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

The Neander Valley, east of Dusseldorf in Germany, was the location for the

discovery of Neandertal 1, the original Neandertal type specimen, in 1856, Mulligan, Copyright 2011

during the removal of deposits from the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte.

All rights reserved

H. heidelbergensis sites

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Early H. sapiens sites

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Skull morphology of Homo

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Skeletal features of Neandertals

and modern humans

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Taxonomic troubles

Number of Species

Relethford

Minimum

Current Maximum

Early Homo sapiens

Homo erectus

Homo ergaster

Archaic humans

Archaic Homo sapiens

Homo antecessor

Homo heidelbergensis

Homo

neanderthalensis

Modern humans

Recent Homo sapiens

Homo sapiens

Homo erectus

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Hominid phylogenies

Milford Wolpoff

G. Phillip Rightmire

Richard Klein

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Molecular genetic data on the

Neanderthals and implications for

gene flow with modern humans

• > 15 Neanderthal mtDNA genome sequences

• 2 Cro-Magnon mtDNA control region sequences

• 2 (low coverage) Neanderthal nuclear genome

sequences

• 1 Denisova mtDNA genome sequence

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Multidimensional scaling of HVRI sequences of 60 modern Europeans

(filled squares), 20 modern non-Europeans (filled circles), 4

Neanderthals (open diamonds), Lake Mungo specimen (open circle),

and Paglicci specimens (open squares)

Conclusion - Modern humans clearly group w/ Cro-Magnon and show

no shared ancestry with Neanderthal

Cro-Magnon

Neanderthal

Caramelli et al. 2003

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Inconsistencies between the two Neanderthal

nuclear genome draft sequences

Noonan et al. 2006

• Human-Neanderthal DNA

sequence divergence time

approximately 706 kya

• 0% contribution of

Neanderthals to human gene

pool

• Neanderthal sequence

carries derived allele for 3%

contribution to modern

human SNPs

• Modern EuropeanNeanderthal population split

time of 325 kya

Green et al. 2006

• Human-Neanderthal DNA

sequence divergence time

approximately 516 kya

• Significant evidence of

Neanderthal-human gene

flow

• Neanderthal sequence

carries derived allele for 30%

contribution to modern

human SNPs

• Modern EuropeanNeanderthal population split

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

time of 35 kya

All rights reserved

New in Science last week

•

New genomic data are settling an old argument about how our species evolved.

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/summary/331/6016/392

– Two instances of interbreeding

• w/ Neanderthal

• w/ Denisova populationNew DNA data suggest not one but at least two instances of interbreeding between

archaic and modern humans, raising the question of whether Homo sapiens at that point was a distinct

species

– Refutes complete replacement

– Doesn’t prove classic multiregionalism

– Suggests a small amount of interbreeding, presumably at the margins where invading moderns

met archaic groups, the ‘assimilation’ model

Modern humans from Africa interbred with Neandertals (pink). Then one group mixed with Denisovans (green) on the way to Melanesia.

Gibbons, Science 2011

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

New in Science last week

• The Species Problem

Our ancestors are now thought to have mated with at

least two kinds of archaic humans at two different times

and places. Were they engaging in interspecies sex, or

does the fact that they were able to produce offspring

mean they were all members of the same species?

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/summary/331/601

6/394

– Paabo says such a discussion is a “sterile academic endeavor”

– John Hawks – “They mated with each other. We'll call them the

same species”

– Hublin says Mayr's concept doesn't hold up: “There are about

330 closely related species of mammals that interbreed, and at

least a third of them can produce fertile hybrids.”

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved

Bottom line

• Most likely, some low level of interbreeding

between Neanderthals (and other archaics?)

with modern humans

• Evidence of this genetic contribution will be

present at low frequency and patchily

distributed geographically

Mulligan, Copyright 2011

All rights reserved