LDL-C (mg/dL)

advertisement

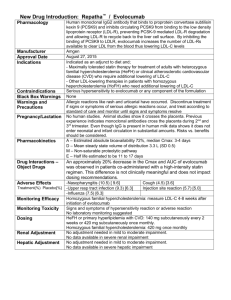

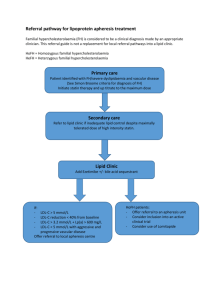

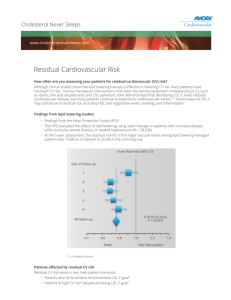

Cardiovascular disease burden and remaining unmet needs Date of Preparation: December 2015 PROES008059 1 Contents • Burden of disease • Causal relationship between LDL-C and CV risk – – – – Large epidemiological studies Genetic studies – PCSK9, Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 Large statin studies IMPROVE-IT study • Unmet needs – Persistent CV risk due to poorly controlled LDL-C despite standard of care therapy – Difficulties achieving LDL-C goals with current standard of care • Diabetes 2 Burden of disease 3 CVD is the number one cause of noncommunicable death globally • A summary of the leading causes of death globally; of the top 10 causes of death globally in 2012, CVD accounted for 28% of all deaths1 The leading causes of death globally1 Percent (%) of deaths 30 25 CVD (ischaemic heart disease, stroke and other cerebrovascular disease) Lower respiratory infections 20 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Diarrhoeal disease 15 10 HIV/AIDS Trachea, bronchus, lung cancers Tuberculosis 5 0 • • • • On average, one American dies from CVD every 40 seconds; equating to approximately 2,200 deaths each day2 Each year, CVD causes over 4 million deaths in Europe and over 1.9 million deaths in the European Union3 >80% of CVD deaths take place in low- and middle-income countries and occur almost equally in men and women4 By 2030, almost 23.3 million people globally will die from CVD annually, mainly from heart disease and stroke5 1. World Health Organization. Factsheet No. 310. http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index.html. Accessed July 2014. 2. Go AS, et al. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. 3. Nichols M, et al. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. 4th ed. Brussels, Belgium: European Heart Network; 2012. 4. World Health Organization Media Centre. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/index.html. Accessed February 12 2014. 5. Mathers CD, Loncar D. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi:10. 1371/journal.pmed.0030442. CVD, cardiovascular disease. 4 There is a high financial burden of CVD CVD is the number one cause of death globally, with a cost US $700 (€515) billion in Europe and USA1,2 • According to the 2012 European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics, total costs to the EU economy as a result of CVD were estimated at almost €196 (US $267) billion per year1 • Between 2010 and 2030, direct medical costs of CVD in the US are projected to triple, from US $273 (€200) billion to US $818 (€588) billion*2 – By 2030, the projected total direct and indirect costs of CVD in the US are expected to exceed US $1 trillion (EU €736 billion)*3 • Direct costs of CVD in Asia are estimated to exceed US $120 (€88) billion per year and are rapidly rising4 *Real (2008 US $) 1. Nichols M, et al. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. 4th ed. Brussels, Belgium: European Heart Network; 2012. 2. Heidenreich PA, et al. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944. 3. Go AS, et al. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. 4. Asia-Pacific Heart Network (2009). Asia-Pacific heart charter. Available at: http://www.world-heart-federation.org/fileadmin/user_upload/images/members_area/News/Asia%20Pacific%20HeartChart%20Consultation.pdf. Accessed February 2015. CVD, cardiovascular disease. 5 Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and its relationship to cardiovascular risk Large epidemiological studies 6 The causal relationship between cholesterol levels and CV risk is well established • A meta-analysis of 61 prospective observational studies of vascular mortality, comprising of nearly 900,000 healthy participants Ischemic heart disease mortality vs total cholesterol • Blood pressure and total cholesterol was measured at baseline to determine the joint relevance of each of these risk factors1 • There is a strong positive relationship between LDL-C reduction with statins and the frequency of CVD events2 – This is also observed in apparently healthy individuals without hypercholesterolemia3 • Patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) have life-long exposure to very high LDL-C levels and typically develop CVD relatively early in life4,5 256 128 Hazard Ratio (95% CI) • There is a continuous positive relationship between CV risk and serum total cholesterol concentrations1 Age at risk (years) 80–89 70–79 64 60–69 32 50–59 16 40–49 8 4 2 1 0.5 4.0 5.0 6.0 7.0 8.0 (mmol/L) 155 193 232 270 309 (mg/dL) Usual total cholesterol (1 mmol/L) Reprinted from The Lancet, 370, Prospective Studies Collaboration, Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths, page 1831, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier. 1. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Lancet. 2007;370:1829–1839. 2. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. 3. Ridker PM, et al. for the JUPITER Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–2207. 4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2008). Identification and management of familial hypercholesterolaemia: NICE clinical guideline 71. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg71. Accessed March 2013. 5. Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 1974;49:476–488. CVD, cardiovascular disease 7 The Framingham Study: Relationship between serum cholesterol levels and CVD mortality • 30 years of follow-up from the Framingham Study, which investigated the relationship between serum cholesterol values and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, found that cholesterol levels were directly related to 30-year CVD and all-cause mortality in individuals under the age of 50 – 5% increase in overall death and 9% increase in CVD death for each 10 mg/dL increase of cholesterol Univariate proportional-hazards model coefficients for cholesterol level and mortality CVD mortality was directly related to total cholesterol levels in the 30-year follow-up from the Framingham study1 1. Anderson KM, et al. JAMA 1987;257(16): 2176–80. †P<0.01 ‡P<0.01 8 MRFIT screening data: Association of serum cholesterol and CHD death in 361,662 men • MRFIT was a large, multicentre cohort study of middle-aged men with high CV risk. Its aim was to determine the risk relationship between serum cholesterol and CHD, and to compare it with the pattern observed between blood pressure and CHD risk 18 14 12 10 8 6 CHD mortality increased progressively above the 20th percentile for serum cholesterol (>181 mg/dL [4.68 mmol/L]) 20th percentile Age-adjusted CHD death rate/1000 men/6 years 16 4 2 0 140 180 220 260 300 160 200 240 280 Serum cholesterol mg/dL 1. Martin MJ, et al. Lancet. 1986;2(8513):933–6. CHD, coronary heart disease; MRFIT, Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial for the Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. 9 The Seven Countries Study: Relationship of serum cholesterol to mortality • This was a 25-year follow-up study of 12,467 men based in seven countries, and across six cohorts. The principal aim was to determine the relative risk of CHD mortality in relation to cholesterol levels Adapted from 1. Verschuren WM, et al. JAMA. 1995;274(2):131–6. CHD, coronary heart disease. 10 ARIC Study: Relationship of LDL-C to CHD in men and women ARIC was a population-based sampling of 15,792 residents, 45 to 64 years old from 4 communities in NC, MS, MN, and MD 4.50 Relative Risk of CHD Adjusted for age and race 10-year follow-up 2.85 Women n=6907 1.80 Men n=5432 1.15 0.75 80 100 120 140 160 180 LDL-C (mg/dL) Adapted from 1. Sharrett AR, et al. Circulation. 2001;104(10):1108–13. ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities; CHD, coronary heart disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol 11 Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and its relationship to cardiovascular risk Genetic studies – PCSK9 and NPC1L1 12 Life-long low LDL-C is associated with significant reductions in cardiovascular risk • Modern hunter-gatherer populations with life-long LDL-C levels of approximately 50–75 mg/dL (1.3–1.9 mmol/L) show little evidence of atherosclerosis1 • People with genetically determined low levels of LDL-C have shown that life-long low LDL-C levels are associated with low CV risk2,3 • A meta-analysis of 312,321 subjects showed that long-term exposure to naturally low levels of LDL-C, resulting from 9 different polymorphisms in 6 genes, was associated with a 54.5% reduction in the risk of CHD for each mmol/L lower of LDL-C2 – The latter study suggests a 3-fold greater reduction in the risk of CHD per unit lower LDL-C than that observed during treatment with a statin started later in life2 1. O’Keefe JH, et al. 2004;43(11):2142–2146. 2. Ference BA, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2631–2639. 3. Benn M, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2833–2842. 13 PCSK9 gain-of-function (GoF) and loss-of-function (LoF) mutations and their effect on LDL-C metabolism and CV risk • PCSK9 GoF mutations are a rare cause of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)1 – PCSK9 GoF mutations first found in 2003 through genotype sequencing of samples taken from the members of two French families with FH2 – Analysis of three genotyping studies and a review article reveals that patients with PCSK9 GoF mutations have high levels of LDL-C, premature atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease (CAD) and other CV complications1,3,4 • In contrast, PCSK9 LoF mutations are a rare cause of familial hypobetalipoproteinemia (FHBL)4 – PCSK9 LoF mutations first found in 2005 in African Americans with FHBL during genetic sequencing of 128 individuals with low LDL-C from the Dallas Heart study5 – A large prospective study relating the incidence of CAD over 15 years with the presence of PCSK9 LOF mutations, revealed that patients with LoF mutations have low plasma LDL-C levels and a consistent reduction in CAD6 1. Abifadel M, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223:394–400. 2. Abifadel M, et al. Nat Genet. 2003;34:154–156. 3. Norata GD, et al. Atherosclerosi.s 2010;208:177–82. 4. Tibolla G et al, Nut Met Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;21:835–843. 5. Cohen J, et al. Nat Genetics 2005;37:161–165. 6. Cohen J, et al. New Eng J Med. 2006;354:1264–72. 14 PCSK9 mutations and effect on LDL metabolism Gain of Function Loss of Function ↓LDL-R levels ↓LDL clearance ↑LDL-R levels ↑LDL clearance ↑LDL ↓LDL High risk for atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) Protection from atherosclerosis and CHD Adapted from 1. Catapano AL and Papadopoulos N. Atherosclerosis. 2013;228(1):18–28. 2. Soufi M, et al. Gene. 2013;521(1):200–3. LDL, Low-density lipoprotein. 15 PCSK9 LoF mutations provide genetic validation for the potential role of PCSK9 inhibition in LDL-C metabolism and clearance • Subjects with loss-of-function mutations in PCSK9: – Have naturally low levels of LDL-C and a reduced prevalence of CV disease (CVD) relative to the general population (based on two large prospective studies looking at the relation between CVD and LoF mutations)1,2 – These LoF mutations are not associated with any detectable clinical abnormalities1,2 Benn et al. JACC 20101 Cohen et al. NEJM 20062 PCSK9 mutation LDL-C reduction vs non-carriers CAD reduction vs non-carriers R46L 13% 30% R46L 15% 47% Y142X or C679X 28% 88% 1. Benn M, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:2833–42. 2. Cohen JC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–72. CAD, coronary artery disease; LoF, loss-of-function. 16 PCSK9 LoF mutations are associated with low LDL-C and low prevalence of CAD events • This was a large prospective study investigating the incidence of CAD over 15 years in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, in relation to the presence of PCSK9 LoF mutations The presence of PCSK9 nonsense mutations significantly reduces the risk of coronary heart disease Nonsense mutation: From The New England Journal of Medicine, Cohen et al. Sequence Variations in PCSK9, Low LDL, and Protection against Coronary Heart Disease, 354, 1268, 1270. Copyright © 2013 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society. *Nonsense mutations include PCSK9142X PCSK9679X. PCSK946L is a substitution mutation. 1. Cohen JC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–72. CAD, coronary artery disease; LoF, loss-of-function. 17 Loss-of-function mutations in PCSK9 are associated with lower serum LDL-C and lower incidence of CHD • This was a large prospective study investigating the incidence of CAD over 15 years in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, in relation to the presence of PCSK9 LoF mutations No mutation (n=3278) 30 50th percentile 12 Frequency (%) 10 0 0 1.3 2.6 3.9 5.2 6.5 7.8 PCSK9142X or PCSK9679X (n=85) 30 CHD (%) 20 8 4 0 20 No PCSK9142X Yes or PCSK9679X 10 0 0 1.3 2.6 3.9 5.2 6.5 7.8 Plasma LDL-C in black subjects (mmol/L) PCSK9 mutations were associated with a 28% reduction in mean LDL-C and an 88% reduction in the lifetime risk of CHD (p=0.008 for the reduction; HR=0.11; 95% CI: 0.02, 0.81; p=0.03) 1. Cohen JC, et al. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1264–72. CHD, coronary heart disease. 18 Inactivating mutations of the NPC1L1 gene is associated with lower LDL-C levels1 • This was a sequencing/genotyping cohort study of 113,094 people with or without CHD disease, to identify inactivating mutations of the NPC1L1 gene and its relationship to CHD risk Estimated difference in LDL-C (95% CI) Number of participants Subgroup Total Carriers European ancestry 4,586 11 -24 (-50 to 2) ARIC 10,754 10 -6 (-30 to 18) WGHS 22,515 11 -11 (-33 to 10) CHD-free controls -13 (-27 to 1) Subgroup total African ancestry CHD-free controls and JHS 2,287 7 -22 (-53 to 10) ARIC 2,671 8 -2 (-29 to 25) -10 (-31 to 10) Subgroup total All participants -45 -10 -12 (-23 to -1) 25 Mean difference in LDL-C (mg/dL) 1. The Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium Investigators. N Engl J Med 2014;371(22):2072–82. ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study; CHD, Coronary heart disease; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1; JHS, Jackson Heart Study; WGHS, Women’s Genome Health Study. 19 Inactivating mutations of the NPC1L1 gene are associated with lower CHD risk • A sequencing/genotyping cohort study of 113,094 people with or without CHD identified inactivating mutations of the NPC1L1 gene • Carriers of the 15 different inactivating mutations had, on average, a 53% reduction in CHD risk compared with non-carriers (OR=0.47; 95% CI: 0.25–0.87; p=0.008) • Carriers of NPC1L1 mutations also had significantly lower levels of: – Total cholesterol (mean adjusted difference, -13 mg/dL [-0.34 mmol/L]; p=0.03) – LDL-C (mean adjusted difference, -12 mg/dL [-0.31 mmol/L]; p=0.04) 1. The Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium Investigators. N Engl J Med 2014;371(22):2072–82. CHD, coronary heart disease; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1. 20 Life-long low LDL-C reduces CHD risk A meta-analysis of 312,321 subjects with long-term exposure to naturally low levels of LDL-C, resulting from 9 different polymorphisms in 6 genes Nearby gene SNP Sample Size (n) OR (95% CI) SORT1 rs599839 141,565 0.88 (0.86—0.90) rs646776 111,900 0.86 (0.86—0.91) rs11206510 186,582 0.94 (0.92—0.96) rs11591147 127,651 0.72 (0.62—0.84) rs65111720 77,041 0.87 (0.83—0.92) rs2228671 82,880 0.89 (0.86—0.93) HMGCR rs12916 49,160 0.94 (0.90—0.98) ABCG8 rs4299376 118,842 0.94 (0.92—0.96) APOE rs4420638 75,487 0.86 (0.83—0.89) PCSK9 LDLR (l-squared = 91.8%, p<0.001 0.70 0.80 0.90 1.0 Life-long exposure to low LDL-C due to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) reduces the risk of CHD by 54.5% for each mmol/L lower of LDL-C1 CHD = coronary heart disease 1. Ference BA, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2631–9. CHD, coronary heart disease. 21 Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and its relationship to cardiovascular risk Large statin and ezetimibe studies 22 Statin trials have also demonstrated that lowering LDL-C reduces CV risk • In addition to large epidemiological and genetic studies, the relationship between LDL-C and CV risk is supported by large statin studies • The degree of LDL-C reduction is strongly associated with reduced risk of CV events1–6 – Lowering LDL-C levels with statins in patients with (secondary prevention) or without (primary prevention) prior CV events has been shown to significantly improve CV outcomes – A lower limit of LDL-C below which there is a definite safety problem and/or no further benefit has not yet been determined2 – Clinical trials with statins have shown increased benefit of reducing LDL-C to low levels (<50 mg/dL)4,5 • Lowering LDL-C to <70 mg/dL has been recommended as an optional target for high-risk patients in the latest European guidelines7 1. LaRosa JC, et al. Am J Cardiol. 2012;111:1221–9. 2. O’Keefe JH, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(11):2142–6. 3. Ference BA, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2631–9. 4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81. 5. Hsia J, et al. JACC. 2011;56(16):1666–75. 6. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2012;380:581–90. 7. Reiner Z, et al. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818. 23 Lowering LDL-C levels in patients with or without prior CV events has been shown to significantly improve CV outcomes • From a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of statins used in primary (N=7) and secondary (N=11) prevention, produced by the NIH/ACC/AHA Task Force1 LDL-C vs CV events 30 Secondary Prevention 1 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Treatment Arm 25 Control Arm (Placebo) Control Arm (Active Comparator) Event Rate (%) 20 1 5 15 5 610 11 9 4 7 2 4 310 11 8 6 Primary Prevention 4 9 8 7 2 3 1 2 51 3 5 6 6 60 4 3 7 7 10 5 2 80 100 120 POSCH (1990) 4S (1994) CARE (1996) LIPID (1998) MIRACL (2001) HPS (2002) A to Z (2004) ALLIANCE (2004) PROVE-IT (2004) IDEAL (2005) TNT (2005) 140 160 180 200 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. WOSCOPS (1995) AFCAPS (1998) ASCOT (2003) CARDS (2004) MEGA (2006) JUPITER (2008) SHARP (2011) LDL-C Achieved (mg/dL) Lowering LDL-C levels in patients with (secondary prevention) or without (primary prevention) prior CV events has been shown to significantly improve CV outcomes Adapted from 1. Raymond C, et al. Clev Clin J Med. 2014;81:11–19. 24 There is a linear relationship between reduction in major CV events and LDL-C reduction in statin trials • A meta-analysis of data from 14 randomized controlled trials (RCT) of statins including 90,056 participants. Weighted estimates were obtained of effects on different clinical outcomes per 1.0 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C1 LDL-C vs. major CV events Proportional reduction in CV event rate (SE) 50% 40% 30% 21% 20% 10% 0% 0.5 -10% 1.0 1.5 19 39 58 Reduction in LDL cholesterol 2.0 (mmol/L) 77 (mg/dL) Adapted from CTT Collaborators, Efficacy and safety of cholesterollowering treatment A later meta-analysis of 26 RCTs involving 170,000 participants demonstrated that with every 1 mmol/L (39 mg/dL) reduction in LDL-C, statins produce a relative risk reduction in major CV events of 22% at 1 year (standard statin dose vs. control)2 1. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78. 2. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81. 25 Effect of statins in reducing LDL-C and CV events: The CTT meta-analysis With every 1 mmol/L (39 mg/dL) reduction in LDL-C, statins produce an approximate relative risk reduction in major CV events of 22% at 1 year (standard statin dose vs. control) Adapted from 1. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81. 26 Very low levels of atherogenic lipoproteins and the risk for cardiovascular events 1.00 40 0.75 30 0.50 20 0.25 10 Percent (%) Hazard ratio • A meta-analysis including individual patient data (N=38,153) from 8 randomized controlled statin trials – conventional lipids and apolipoproteins were determined for each participant at baseline and at 1-year follow-up Distribution of achieved onstatin LDL-C levels Risk of major CV events 0 0 0 30 50 100 150 200 250 (mg/dL) 1.3 2.6 3.9 5.2 6.5 (mmol/L) LDL-C Patients who achieve very low LDL-C levels (<50 mg/dL) have a lower risk for major cardiovascular events than those achieving moderately low levels1 1. Boekholdt SM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:485–94. 27 Effect of the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy in reducing CV risk: IMPROVE-IT study design Patients stabilized post ACS ≤ 10 days: LDL-C 50–125*mg/dL (or 50–100**mg/dL if prior lipid-lowering Rx) N=18,144 Standard Medical & Interventional Therapy Simvastatin 40 mg (N=9077) Uptitrated to simvastatin 80 mg if LDL-C > 79 mg/dL Ezetimibe / Simvastatin 10 / 40 mg Follow-up visit Day 30, every 4 months (N=9067) 90% power to detect ~9% difference Duration: Minimum 2½-year follow-up (at least 5250 events) Primary Endpoint: CV death, MI, hospital admission for UA, coronary revascularization (≥ 30 days after randomization), or stroke 1. Cannon CP, et al. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Session LBCT.02 November 17, 2014, Chicago. *3.2mM **2.6mM ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina 28 IMPROVE-IT: Mean LDL-C at 1 year, ITT and OT 100 LDL-C values at 1 year LDL-C (mg/dL) 90 Simva ITT : LDL-C 69.9 mg/dL Simva OT: LDL-C 69.5 mg/dL EZE+Simva OT: LDL-C 52.5 mg/dL EZE+Simva ITT: LDL-C 53.2 mg/dL 80 ITT: ΔLDLC 16.7 mg/dL OT: ΔLDLC 17.0 mg/dL Simvastatin 70 ITT OT 60 Ezetimibe/Simvastatin ITT 50 OT 40 QE 4 mo 1 yr Randomization 2 yrs 3 yrs 4 yrs 5 yrs 6 yrs 7 yrs 8 yrs Time since randomization 1. Cannon CP, et al. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Session LBCT.02 November 17, 2014, Chicago. ITT, intent to treat; OT, on-treatment. 29 IMPROVE-IT: Primary endpoint on-treatment 40 CV event rate Simvastatin — KM 32.4% 2079 events HR=0.924 CI: 0.868, 0.983 p=0.012 Event rate (%) 30 Ezetimibe/Simvastatin — KM 29.8% 1932 events 20 7.6% Treatment effect 10 Primary Endpoint: CV death, MI, hospital admission for UA, coronary revascularization (> 30 days after randomization), or stroke 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Time since randomization (years) 1. Cannon CP, et al. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Session LBCT.02 November 17, 2014, Chicago. 30 IMPROVE-IT: Summary • Key findings: – Lowering LDL-C with non-statin agent (i.e. ezetimibe) on top of simvastatin (-17 mg/dL treatment difference vs. simvastatin alone) reduces the risk of cardiac events in post-ACS patients by a further 7.6% (HR=0.924; 95% CI: 0.868, 0.983; p=0.012) – Lowering LDL-C levels (even modestly) beyond those achieved by statins reduces CV event rates further1 When added to statin therapy, ezetimibe achieves greater LDL-C and major CV event reductions than statins alone 1. Cannon CP, et al. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Session LBCT.02 November 17, 2014, Chicago. 31 Unmet needs Persistent CV risk due to poorly controlled LDL-C despite treatment with standard of care 32 Patients with high CV risk face challenges in achieving LDL-C goals (predominantly US data) • Statins are the standard of care for HC management • However, many patients are not reaching their recommended LDL-C goal with statin therapy1-3 High risk patients1 LDL-C Goal <100 mg/dL 23% not at goal LDL-C Goal <70 mg/dL 76% not at goal 1. Jones PH, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e001800. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.001800. 2. Stein EA, et al. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1287–1293. 3. Pijlman AH, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:189–194. HC, hypercholesterolemia; HeFH, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. HeFH patients2,3 LDL-C Goal <100 mg/dL ~80% not at goal 33 Despite statin therapy, many high-risk patients have marked LDL-C elevations (EU) • Cross-sectional, observational study of statin-treated patients (N=22,063) to assess the prevalence of persistent dyslipidemia in relation to CV risk factors. European Society of Cardiology recommendations were used to classify patient risk, and to define LDL-C goal and normal levels for HDL-C and triglycerides1 1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) 0.6 Density 0.5 0.4 LDL-C 2.5 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) 46.8% 0.3 0.2 Non high-risk 0.1 High-risk 0 0 1 2 3 4 LDL-C (mmol/L) 5 6 7 Despite statin therapy, 46.8% high risk patients have LDL-C levels ≥2.5mmol/L (≥100 mg/dL) 1. Gitt AK, et al. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:221–30. 34 Only a small proportion of patients with HeFH reach the LDL-C treatment target of <2.5mmol/L • A large cross-sectional study of 1,249 lipid clinic outpatients with known HeFH that recorded data on the use of lipidlowering therapy, plasma lipids and lipoprotein levels, safety, and reasons for not achieving treatment goals Attainment of Target (%) Proportion of HeFH patients at LDL-C target for different treatment goals 100 80 60 40 20 0 1 2 2.5 3 4 5 5 7 8 9 10 LDL-C Target (mmol/L) Only 21% of patients with HeFH reach the treatment target for LDL-C of <2.5mmol/L1 1. Pijlman AH, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209(1):189–194. HeFH, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. 35 Key patient populations may need additional LDL-C lowering therapies Patients who could benefit from additional lipid lowering therapy Magnitude of impact High-risk patients with poorly controlled LDL-C despite treatment with standard of care1 Up to 76% of high risk patients fail to reach their LDL-C goal of less than 70mg/dL1 Those who cannot or will not take statins due to adverse effects2,3 10–20% of patients treated with high dose statins show some degree of statin intolerance2,7,8 40–50% of patients are non-adherent at 1 year9,10 Familial hypercholesterolemia • at high risk of premature coronary disease4 and who fail to reach their LDL-C goal5,6 Approximately 80% of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia failed to reach an LDL-C target <100mg/dL11 1. Jones PH, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e001800. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.001800. 2. Bruckert E, et al. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19(6):403–14. 3. Cohen JD, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6:208–15. 4. Rees A. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2583–4. 5. Stein EA, et al. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1287–93. 6. Pijlman AH, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:189–94. 7. Arca M, et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:155–66. 8. Betteridge DJ, et al. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;doi:10.1038/nrendo.2012.254. 9. Avorn J, et al. JAMA. 1998;279(18):1458–62. 10. Casula M, et al .Patient Preference and Adherence 2012;6:805–14. 11. Stein E, et al. Am Heart J. 2004;148: 447–55. 36 International guidelines recommend lowering LDL-C is the primary treatment objective in patients with hypercholesterolemia, with or without a history of CVD Approx. LDL-C relative reduction from baseline ≥50% 30%–50% High CV risk Moderate intensity statin High intensity statin Treat level of ASCVD risk based on age and tolerability ESC/EAS 2011 guidelines for the management of dyslipidemias2 Very high CV risk ACC/AHA 2013 guidelines on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce ASCVD in adults1 LDL-C target <70 mg/dL <100 mg/dL 1. Stone NJ, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25):2889–934. 2. Reiner Z, et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818. 3. Grundy SM, et al. Circulation. 2004;110:227–39. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease. 37 Persistent CV risk despite treatment with standard of care therapy • Persistent CV risk due to elevated lipids may be reduced by the additional lowering of: – – – – LDL-C2,3 Non-HDL-C3 ApoB3 Lp(a)4,5 Patients with persistent CV risk despite treatment with standard of care therapy may benefit from additional lipid-lowering options1,2 1. Pöss J, et al. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2011;17:861–70. 2. Wiviott SD, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1411–6. 3. Boekholdt SM, et al. JAMA. 2012;307:1302–9. 4. Kamstrup PR, et al. JAMA. 2009;301:2331–9. 5. Nordestgaard BG, et al. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2844–53. 38 Unmet needs Difficulties achieving LDL-C goals with current standard of care 39 Difficulties achieving LDL-C goals with statins • Increasing the statin dose can lower LDL-C further and improve CV outcomes1-3 – However, high statin doses are underutilized4 and are generally associated with decreased tolerability1-3,5 • Even with high-potency statin therapy*, only 33% of high-risk patients with the most difficult to treat hypercholesterolemia are able to adequately control their LDL-C levels4 • Statin resistance, which is not well defined, also prevents patients from reaching their LDL-C goal – Patients do not always respond to statin therapy4 • Beyond statins, therapeutic options are limited6-8 *High potency statins defined as atorvastatin (40 mg or 80 mg), rosuvastatin (20 mg or 40 mg), or simvastatin 80 mg. 1. Cannon CP, et al. N Engl J Med. 2004:350(15):1495–504. 2. LaRosa JC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1425–35. 3. Pedersen TR, et al. JAMA. 2005;294:2437– 45. 4. Karalis DG, et al. Cholesterol. 2012; doi:10.1155/2012/861924. 5. Bruckert E, et al. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19(6):403–14. 6. HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1279–91. 7. The AIM-HIGH Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–67. 8. Reiner Z, et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818. 40 Patients who poorly tolerate statin therapy may have difficulty achieving LDL-C goals • 10%–15% of patients treated with high-dose statins show some degree of statin intolerance1 • Some patients on statin therapy are unable to achieve their LDL-C goal because of adverse events2 – In the Prediction of Muscular Risk in Observational (PRIMO) study population, 10.5% of patients on high-dose statin therapy complained of muscle pain3 – Recent trials have reported the incidence of statin-related muscle symptoms to be as high as 16%4 Due to statin intolerance, limited and variable efficacy of statin therapies, some high-risk patients may remain at elevated CV risk5 1. Arca M, et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:155–66. 2. Karalis DG, et al. Cholesterol. 2012;1–7. 3. Abd TT. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10(3):373–87. 4. Ridker PM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–207. 5. Reiner Z, et al. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818. 41 Identifying true statin intolerance • Prevalence of statin intolerance is difficult to define and there is no universally accepted definition • Some patients can be successfully rechallenged, questioning the diagnosis • Patient preference also plays a role Statin intolerance is a clinical syndrome that is: i. Characterized by inability to use statins long-term due to significant symptoms and/or biochemical abnormalities ii. Either ‘complete’ (intolerant to any statin at any dose) or ‘partial’ (intolerant to some statins at some doses) iii. Not attributable to established predispositions such as drug-drug interactions, untreated hypothyroidism, febrile illness, etc1 1. Mancini GB, et al. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(12):1553–68. 42 PRIMO: Risk of muscle symptoms with high-dose statins Dosage Percentage of patients with muscular symptoms* Pravastatin 40 mg/day 10.9% Atorvastatin 40–80 mg/day Simvastatin Fluvastatin Statin Odds ratio† (95% CI) p-value‡ 14.9% 1.28 (1.02, 1.60) 0.035 40–80 mg/day 18.2% 1.78 (1.39, 2.29) <0.0001 80 mg/day 5.1% 0.33 (0.26, 0.42) <0.0001 * % values relative to the total number of patients with or without muscular symptoms † Odds ratios were calculated using pravastatin as the reference ‡ p values were determined by Pearson’s Chi-squared test 1. Bruckert E, et al. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 2005;19:403–14. 43 Clinical trials and muscle-related adverse effects Why the low incidence in clinical trials? • Patients highly selected • Often have pre-randomization ‘run-in’ • Definitions of muscle adverse effects differ • Motivated trial patients may minimize symptoms • Muscular aches and pains are common in placebo group1 1. Mancini GB, et al. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:635–62. 44 Summary: Why are cholesterol targets not achieved? • Over-reliance on diet and lifestyle changes • Insufficient starting doses of statins • Inability to reach more aggressive targets even with high dose statin • Lack of follow-up for uptitration • Complacency/inertia with sub-optimal cholesterol values achieved • Confusion around recommended lipid targets • Fear of side effects of statins • Statin intolerance 45 New treatment options in development 46 Non-statin alternative therapies in development: Emerging options • PCSK9 inhibitors to increase LDL receptor levels1–4 • Apolipoprotein B (apoB) inhibitor5 • Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) inhibitor5 • Cholesterol transport (CETP) inhibitors – increase HDL and decrease LDL6 *Investigational products 1. McKenney JM, et al. JACC. 2012;59(25):2344–53. 2. Robinson JG. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(2):139–49. 3. Giugliano RP, et al. Lancet 2012;380:2007–15. 4. Koren MJ, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(23):2531–40. 5. Rader DJ, et al. Circulation 2014; 29(9):1022–32. 6. Mabuchi H, et al. Mol Cells. 2014;37(11):777–84. 47 Overview of PCSK9-directed therapies in development1–7 Company Drug Agent Indication Phase Inhibition of PCSK9 binding to LDL-R Sanofi/Regeneron Alirocumab Fully Human mAb Hypercholesterolemia 3 Amgen Evolocumab Fully Human mAb Hypercholesterolemia 3 Pfizer/Rinat Neuroscience Bococizumab mAb Hypercholesterolemia 3 Novartis LGT209 mAb Hypercholesterolemia 2 Roche/ Genentech RG7652 mAb Hypercholesterolemia 2 LY3015014 mAb Hypercholesterolemia 2 Adnexins Hypercholesterolemia 1 ALN-PCS02 siRNA oligonucleotides Hypercholesterolemia 2 TBD Antisense oligonucleotide Hypercholesterolemia Preclinical Eli-Lilly PCSK9 protein binding fragment BMS/Adnexus BMS-962476 Inhibition of PCSK9 synthesis (gene silencing) Alnylam Idera Inhibition of PCSK9 autocatalytic processing Seometrix SX-PCK9 Small peptide mimetic Hypercholesterolemia Preclinical Shifa Biomedical TBD Small molecule Metabolic Disorders Preclinical Cadila Healthcare TBD Small molecule Preclinical mAb: monoclonal antibody 1. Rhainds D, et al. Clin Lipidol 2012;7:621–40. 2. Lambert G, et al. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2515–24. 3. Clinicaltrials.gov. RUTHERFORD-2, NCT01763918. 4. Clinicaltrials.gov. SPIRE-HR, NCT01968954. 5. Nature Reviews: Drug Discovery. Selected PCSK9-targeted agents in development. Available at: http://www.nature.com/nrd/journal/v11/n5/fig_tab/nrd3699_T5.html. Accessed Feb 2015. 6. Clinicaltrials.gov. LY3015014, NCT01890967. 7. Stein EA, Swergold GR. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013:15:310. mAB, monoclonal antibody; siRNA, short interfering RNA. 48 Most advanced PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies in development: Phase III programmes Alirocumab Evolocumab Patient Min Length Exposure LDL-C (M) (Y) (mg/dL) DB Trials ODYSSEY N FH I 471 18 496 ≥100 FH II 250 18 250.5 ≥100 HIGH FH 105 18 106.5 ≥160 COMBO I 306 12 210 ≥ 70 COMBO II 660 24 960 ≥70 OPTIONS I 350 6 50 ≥70 OPTIONS II 300 6 50 ≥70 MONO 100 6 25.5 ≥100 Statin ALTERNATIVE Intolerant 250 6 50 ≥70 Long term LONG-TERM 2100 18 2340 ≥70 HeFH Combo Tx Mono Tx Total N of Patients 4892 ~4538 patient-yrs in DB controlled trials DB Trials N RUTHERFOR D-2 300 LAPLACE-2 1700 Bococizumab Patient Min Length Exposure LDL-C (M) (Y) (mg/dL) 3 3 46 231 ≥100 N Lenght (M) SPIRE-HF 300 12 200 ≥70 SPIRE-HR 600 18 600 ≥70 SPIRE-LDL 1600 18 1600 ≥70 939 12 626 >100 ≥80 MENDEL-2 600 3 92 ≥100 GAUSS-2 300 3 46 None GAUSS-3 500 3 NA NA DESCARTES 905 12 602 ≥75 Total N of Patients 4305 Patient Min Exposure LDL-C (Y) (mg/dL) DB Trials ~1017 patient-yrs in DB controlled trials PLANNED SPIRELL ~3000 patient-yrs (assumes 2:1 Total N of Patients randomization, final N 3439 likely to be larger as anticipate additional trials) ClinicalTrials.gov. available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed August 10, 2014. DB, double blind; min, minimum 49 CETP inhibitors in development: Impact on HDL-C and LDL-C • Greatest impact on HDL-C, some effect on LDL-C as either monotherapy or in combination with statin therapy Anacetrapib1–3 Evacetrapib4 Dalcetrapib1,5 Torcetrapib1 Complete inhibition No data Modulation (selective inhibition) Complete inhibition HDL increase 24 weeks: 138% 2-yr extension: 153% 12 weeks: 129% 31% 72% LDL decrease 24 weeks: 40% 2-yr extension: 40% 12 weeks: 36% No change 25% Phase II Primary prevention Discontinued -lack of clinical outcome benefit Discontinued increases in cardiovascular events and total mortality dal-OUTCOMES ILLUMINATE Effect on CETP Clinical status Phase III DEFINE DEFINE-extension Phase III REVEAL (outcome) Phase III ACCELERATE (outcome) 1. Shinkai H. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2012;8:323–31. 2. Cannon CP, et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2406–15. 3. Gotto AM Jr, et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19(6):543-9. 4. Nicholls SJ, et al. JAMA 2011;306(19):2099–109. 5. Schwartz GG, et al, dal-OUTCOMES Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(22):2089–99. CETP, Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein 50 Diabetes 51 Diabetes and CVD risk • Diabetes mellitus independently raises the risk of CVD1 – The UKPDS23 demonstrated that, in T2DM, patients with high LDL-C were >2x as likely to develop CAD compared with those with low LDL-C2 • CVD is the most common cause of death in patients with diabetes – 44% in type 1 diabetes and 52% in type 2 diabetes3 • Patients with diabetes are also more prone to dyslipidemias in the form of: – – Hypertriglyceridemia – approximately 18% of patients with T2DM vs. 8.5% in those without diabetes Low HDL-C levels – twice as high as in patients without diabetes4 • Insulin resistance may also lead to higher levels of small dense LDL-C4 • Type 2 diabetes increases the risk of both micro- and macrovascular complications3 – Data from the 1999–2004 NHANES indicate that the prevalence of microvascular complications is significantly higher than that of macrovascular complications5,6 • A prospective observational study of 4,585 patients with type 2 diabetes from the UKPDS study found that, for every 1% reduction in HbA1c, there was a: – – 37% decreased risk of microvascular complications (33–41%, p<0.0001) 14% decreased risk of combined fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction (8–21%, p<0.0001)7 1. Reiner Z, et al. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(14): 1769–818. 2. Turner RC, et al. BMJ .1998;316:823–8. 3. Morrish NJ, et al. Diabetologia. 2001;44(suppl 2):S14–S21. 4. Moodarian AD, et al. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2009;5(3):150–9. 5. Deshpande AD, et al. Phys Ther. 2008;88:1254–64. 6. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. State of diabetes complications in America. Available at: https://nfb.org/images/nfb/publications/vod/images/complications_press_release.doc . Accessed Feb 10, 2015. 7. Stratton IM, et al. BMJ. 2000;321:405–12. CAD, coronary artery disease; UKPDS, UK prospective diabetes study; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination 52 Lipid lowering is effective in type 2 diabetes • The effect of statin therapy in 18,686 individuals with type 2 diabetes was evaluated from 14 randomized statin trials (≥1,000 participants; treatment duration ≥2 years). The mean duration of follow-up was 4.3 years 0 Major vascular events Percentage (%) -5 All-cause mortality -9% -10 -15 -21% -20 -25 Reductions per 1.0 mmol/L There was a 21% reduction in major CV events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C in patients with T2DM treated with statins Adapted from 1. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CCT) Collaborators, et al. Lancet 2008; 371(9607):117–25. T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus 53 LDL-C goal achievement by diabetes status in a UK primary-care database (2008–2011; N=2999) • Only half of atorvastatin-treated patients with diabetes achieved LDL-C <2.0 mmol/L • Goal achievement was highest on atorvastatin 80 mg, yet only 12% of patients received this maximum dose Patients with LDL-C <2.0 mmol/L (%) 100 58.8 60 Atorvastatin 10 mg 66.2 80 49.7 49.9 50.9 53.9 Atorvastatin 20 mg 56.9 54.5 50.9 43.9 Atorvastatin 40 mg Atorvastatin 80 mg All doses 40 20 0 DM CHD/AVD + DM CVD risk group 1. Jameson K, et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:655–65. DM, diabetes mellitus; CHD, coronary heart disease; AVD, atherosclerotic vascular disease 54 Prevalence of meeting ABC goals among adults with diagnosed diabetes (NHANES 1988–2010) 60 50 † * Patients (%) 1988–1994 1999–2002 2003–2006 2007–2010 † † 40 * * * *p<0.01 vs 2007–2010 data † p<0.05 vs 2007–2010 data 30 20 * 10 0 * * A1C <7.0% BP <130/80 mmHg LDL-C <2.6 mmoI/L ABC Adapted from 1. Stark Casagrande S, et al. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2271–9. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; BP, blood pressure; ABC = HbA1c (A), Blood pressure (B) and LDL-C (C) 55 Summary of recent international guideline recommendations on lipid management in patients with diabetes Recommended treatments and LDL-C goals ADA 20151 • • ACC/AHA 20132 ESC/EASD 20133 Moderate-intensity statin: • Diabetes aged <40 y with additional CV risk factors • Diabetes aged 40–75 y without additional CV risk factors High-intensity statin: • Diabetes aged <40 y with CVD • Diabetes aged 40–75 y with additional CV risk factors T1/T2DM aged 40-75 y: • Moderate-intensity statin: diabetes aged 40–75 y • High-intensity statin: diabetes and estimated 10-year ASCVD risk ≥7.5% • T1/T2DM at very high-risk (overt CVD, severe CKD or ≥1 CV RFs): LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L (<70 mg/dL) or at least a ≥50% LDL-C reduction if goal cannot be reached • T2DM at high risk (without any CV RFs): LDL-C <2.5 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL) 1. ADA. Diabetes Care. 2015;38 (suppl 1):S49–57. 2. Stone NJ, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25):2889–934. 3. Ryden L, et al. ESC/EASD Guidelines on diabetes. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(39):3035–87. CVD, cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; RF, risk factor; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. 56 57