Hawo Master Thesis

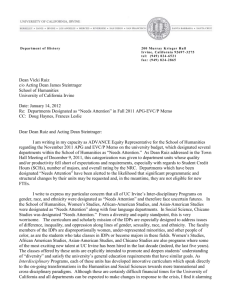

advertisement