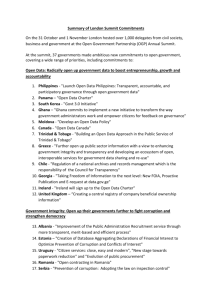

UK IRM Report 2013-2015 Google Doc Public Comments

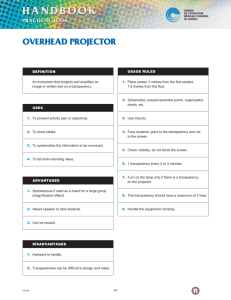

advertisement