World War 2 Handout

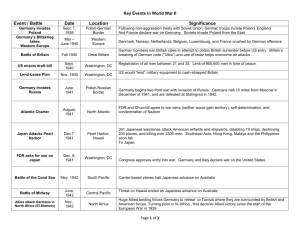

advertisement

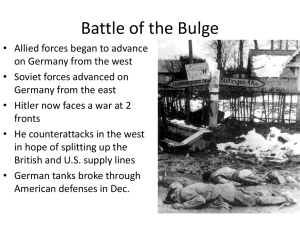

Handout 13: World War II Japanese Relocation: Just as in World War I, the government and media worked hard during World War II to convince Americans that the nation’s enemies were evil. World War II propaganda against the Japanese was particularly harsh, as the Japanese were often portrayed as being less than human. Hostility toward the Japanese had unfortunate consequences at home, as in early 1942 the government ordered that over 110,000 people of Japanese descent be removed from the West Coast, where it was feared they would aid Japan. Two-thirds of the people who were relocated to inland internment camps were American citizens (or "Nisei"; the other third were non-citizens known as "Issei"). Many of the internees lost everything they had because of the relocation. In 1988, the U.S. government formally apologized for what is now generally seen as one of the darker episodes in American history, and provided $20,000 to each of the 62,000 internees who were still living. (For more information see the readings in First Person Past and American Journey.) Early War in the Pacific: For months after Pearl Harbor all of the news from the Pacific was bad for the U.S. In early 1942, in the largest surrender in U.S. history, the Japanese took control of the Philippines. If the Japanese had stopped with the empire they now controlled, they might have been able to hold on to it. But they succumbed to what one Japanese officer called "victory disease" and overextended themselves. The turning point in the Pacific was the Battle of Midway (June of 1942), at which the U.S. inflicted losses on the Japanese that they would not be able to make up. After Midway, the war would drag on for three more bloody years, but the tide had turned, as momentum began to shift from the Japanese to the Americans. The War Against Germany: Despite these early battles in the Pacific, from the beginning of the war the U.S. and Great Britain agreed that their top priority was to defeat Hitler’s Germany, which was deemed the greater military threat. Japan could be finished off after Germany surrendered. The U.S. and Great Britain – the "Western Allies" – worked very closely together in planning and fighting the war. There were tensions between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, however, which was fighting a savage war against Germany in the East. One recurring source of tension was the issue of a "Second Front." With Western Europe under his control, Hitler could concentrate his forces on attempting to defeat the Soviet Union. Joseph Stalin desperately wanted the Western Allies to open up a Second Front by invading Western Europe, thus forcing Germany to divided its forces between Eastern and Western Fronts. FDR repeatedly promised Stalin that a Second Front was imminent, but the more cautious Churchill always forced delays. Stalin, suspicious of western intentions, believed that the Western Allies were simply content to sit back and allow the Soviets to do all of the fighting and dying in the war against Hitler. The British, Americans, and Soviets remained Allies, but there were always undercurrents of suspicion and mistrust between them. North Africa: The U.S. entered the land war against Germany by invading North Africa on Nov. 8, 1942, in order to help British forces which were fighting the Germans there. In May 1943 the last German forces in North Africa surrendered. While the fighting in North Africa was still going on, FDR and Churchill met in Casablanca, Morocco (January 1943) to plan for the future. Stalin could not attend, but urged the Western Allies to agree to open a Second Front in Western Europe. Instead, at Churchill’s urging, the U.S. and British agreed that the next step would be to invade "soft underbelly" of the Axis Powers, meaning Sicily and then Italy. FDR also announced at the Casablanca Conference that the war would only end with the "unconditional surrender" of each of the Axis Powers. Italy: In July, the Western Allies invaded Sicily, which they secured by mid August, and then in September they invaded the Italian peninsula. The Italians pulled out of the war, but the Germans were unwilling to give up the territory and poured their own troops into Italy to stop the Western Allies. A long and bloody war would be fought on the Italian peninsula for the remainder of the world war. Meanwhile, the first meeting of the "Big Three" – FDR, Churchill, and Stalin – took place in Teheran, Iran in late 1943. At this conference the Western Allies agreed to open a Second Front in Western Europe as soon as they could in 1944. D-Day: In January of 1944 Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower – who would be the Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Western Europe – arrived in London to begin preparations for "Operation Overlord," the invasion of France. Tens of thousands of troops and thousands of tons of equipment were gathered in England in preparation for the invasion, while the Western Allies worked to deceive the Germans as to the planned locations of the Allied landings. On June 6, 1944 – "D-Day" – 150,000 men and 4,000 ships took part in the largest seaborne invasion in the history of the world. Landing at beaches along the coast of Normandy, the Allies held their ground and within two weeks had poured a million men into France. The Western Allies then fought into the interior of France, liberating Paris on August 25 and taking control of most of France and Belgium by mid September. Allied leaders spoke of possible victory over the Germans by Christmas, but at this point the Allied advance stalled, having outrun its supply lines. Battle of the Bulge: Hitler’s last, desperate offensive against the Western Allies began by surprise on December 16, 1944, when 250,000 German troops slammed into a weak spot in the Allied lines held by 80,000 American troops. The Germans hoped to fight their way to the crucial port of Antwerp, dividing the British from the American armies and forcing a negotiated peace in the West. The Germans pushed an 80-mile "bulge" into the Allied lines and besieged the key crossroads city of Bastogne, but the Americans regrouped and counterattacked, and by mid January had restored the Western Front to roughly its place before the German attack. The Battle of the Bulge surpassed Gettysburg as the bloodiest battle in American history, as the U.S. suffered 55,000 casualties. But the battle shattered what was left of German power and morale, and now it was just a matter of time before Germany was crushed between the advancing Western Allied and Soviet armies. Victory in Europe: FDR died suddenly on April 12, 1945, making Harry S. Truman the new President. Germany’s surrender occurred less than one month later: Hitler committed suicide on April 30, Berlin surrendered on May 2, and then all of Germany surrendered on May 7. This sparked massive celebrations in Europe and the U.S., but the excitement was tempered by the realization of the enormous human cost of the war, by mourning of FDR, and by the discovery late in the war of the Nazi death machine that had perpetrated the Holocaust – the slaughter of some 6 million Jews – and had exterminated some 5 million other people deemed "inferior" by Hitler’s regime. There was also the knowledge among those who celebrated Hitler’s defeat that there was still a war left to fight, against Japan. Advancing on Japan: During 1943 and 1944 American forces slowly advanced through the Pacific, fighting savage battles against the Japanese on steamy, jungle-filled islands. After the largest naval battle in history – the October 1944 Battle of Leyte Gulf – the Americans regained control of the Philippines. The battle destroyed most of what was left of the Japanese navy, and was the scene of the first Japanese "kamikaze" attacks. In February of 1945, the Americans took six weeks and lost 7,000 men killed in conquering the tiny island of Iwo Jima, which was crucial to the American air war against Japan. From April to June 1945, the Americans fought an even larger and more costly battle for control of Okinawa, which would provide a staging area for the eventual Allied invasion of Japan, planned to begin in November 1945. 50,000 Americans were killed, wounded, or missing as a result of Okinawa, and thousands of Japanese kamikaze attacks sank 34 American ships and damaged hundreds more, while the U.S. destroyed the remnants of the Japanese navy. The Japanese killed almost every American prisoner they took at Okinawa. The End Nears: By early 1945 the U.S. was conducting massive bombing raids over Japan, destroying vast chunks of cities and killing tens of thousands of people. On one air raid against Tokyo on the night of March 9, 1945, U.S. planes dropped incendiary bombs that killed 80,000 people. Still, despite the devastation that the Japanese were suffering, U.S. war planners saw no indication that Japan was seriously considering surrender and believed that an invasion of the Japanese mainland was unavoidable. Given the fanaticism with which the Japanese had fought to defend small islands in the Pacific, it was feared that such an invasion would result enormous casualties on both sides. But then, in the summer of 1945, a force emerged that made the planned invasion unnecessary. The Manhattan Project: In 1939, the famed scientist Albert Einstein wrote FDR to warn him that advances in physics suggested the possibility of splitting atoms in a way that could be used to produce a devastating new weapon. Einstein cautioned FDR that the Germans might be working on such a weapon. After the U.S. entered the war, FDR ordered the beginning of a top-secret program – code named the Manhattan Project – to develop an atomic bomb as rapidly as possible. Gen. Leslie Groves was placed in charge of the project, and was told that he could have whatever money, material, and manpower he needed. Ultimately the U.S. spent some $2 billion dollars on the project. 200,000 people worked on the project in one capacity or another, though only a very few of them knew what the ultimate goal of the project was. The project succeeded spectacularly on July 16, 1945, when the first-ever atomic bomb was detonated in the desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico. American leaders decided that in order to deliver the psychological shock necessary to force Japan to surrender, the bombs would have to be dropped without warning on occupied cities. After Japan rejected a U.S. and British ultimatum to surrender or face "prompt and utter destruction," the U.S. dropped the first bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Approximately 80,000 people were killed instantly, and tens of thousands died afterward from the effects of the bomb. The Japanese government was deadlocked over the issue of surrender, and on August 9 the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb, this time on Nagasaki, where 36,000 people were instantly killed. Soon afterward, the Japanese agreed to surrender on one condition: that the Japanese Emperor be allowed to remain on the throne (though he would be under the command of American occupation forces). Japan formally surrendered on September 2, 1945. Historians and others still argue about whether or not the U.S. was justified in dropping the devastatingly deadly atomic bombs. Consequences: World War II – the bloodiest and most costly by far in the history of the world – killed an estimated 15 million military personnel and 35 million civilians. The Soviet Union alone lost more than 20 million people. The U.S. lost some 408,000 killed. The war involved an estimated $1 trillion in expenditures and destroyed some $2 trillion worth of property. The war also left the United States the most powerful country in the world, and set the stage for a long conflict between the U.S. and its new postwar rival the Soviet Union.