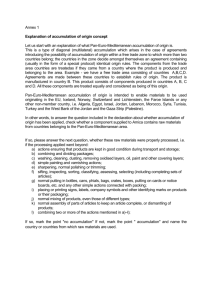

DOCX - 5.1 Mo

advertisement