Cultural Translation: Azur et Asmar

advertisement

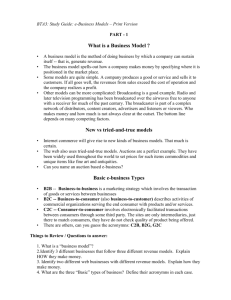

His fourth animated feature film His first Kirikou et la sorcière (1998) was a great success (Kirikou effect in France) Azur et Asmar also set partly in Africa Focus on “transnational cinema” “as scores of transnational films have illustrated in various generic modes, leaving one’s homeland entails leaving behind both physically and emotionally the familiarity that home implies. This leave-taking often entails, to use Freud’s term, a becoming-unheimlich both to oneself and to those who are variously invested in the diasporic subject’s remaining recognizable.” (Ezra & Rowden, Transnational Cinema in the Film Reader) “… borders are always leaky and there is a considerable degree of movement across them …. It is in this migration, this border crossing, that the transnational emerges. … The experience of border crossing takes place at two broad levels. First there is the level of production and the activities of filmmakers. … The second way in which cinema operates on a transnational basis is in terms of the distribution and reception of films. … when films do travel, there is no certainty that audiences will receive them in the same way in different cultural contexts” (Higson, “The Limiting Imagination of National Cinema”) Focus in Africa again, which embarks on a transcendence of all types of boundaries, a perpetual translation or transportation between the two cultures, the Orient and the Occident, thus promoting a mutual complementarity contact between its viewers, mostly children in the West, and a different culture awareness of the position of the immigrant in contemporary societies Hostility toward immigrants in general in the Western, developed world, and toward those of Arab origin in particular, (‘invasion’ of immigrants in the continent). Borders are of paramount importance in relation to immigrants who are excluded from a process of opening up, or even completely eliminating, all forms of boundaries when capital and the larger economy are concerned. ‘[…] such a dual-policy regime [is] viable when it comes to access to the EU: on the one hand, lifting multiple restrictions on access by nonEU firms, investment capital and goods in the context of WTO, and the general opening of financial markets in the European economies, and on the other, building a Fortress Europe when it comes to immigrants and refugees’ (Saskia Sassen, Guests and Aliens) New immigration bill adopted in France in 2006 (DNA tests, French language tests, other biometric tests) these provisions ‘[are] part of the general strategy and managerial logic based on the rationalization of processes and procedures, leading to the fundamental transformation of a conception of society once based on mutual trust into a situation of generalized suspicion’ (Merzouki, http://www.edri.org/edrigram/number4.20/dnafrench-immigration-law). Ocelot’s film attempts a reversal of roles. The film inhabits Arab culture, embarks on a series of boundary crossings – literal and metaphorical Finally manages a reversal of roles, turning the Self into the Other transferences between cultures – be it the physical trans-portations of individuals, spatial or temporal dis-placements, alternations between languages ‘in-between’ space that undermines contemporary fixities “By drawing on more than one culture, more than one language, more than one world experience, within the confines of the same text, postcolonial Anglophone and Francophone literature very often defies our notions of an ‘original’ work and its translation. Hence, in many ways these plurilingual texts in their own right resist and ultimately exclude the monolingual and demand of their readers to be like themselves: ‘in between’, at once capable of reading and translating, where translation becomes an integral part of the reading experience” (Samia Mehrez “Translation and the Postcolonial Experience: The Francophone North African Text”) “authors” of French origin, like Michel Ocelot, who were born and grew up in Africa, are also positioned in this space of “in between”, of not belonging, which makes them “[assume] their bilingualism as an effective means with which to contest all forms of domination, and all kinds of exclusion within their own ‘native’ cultures and their ‘host’ cultures as well” (Mehrez). Born and grew up in North Africa identifies himself with the North African immigrant in France and hints at the frustration he experienced as an adolescent because of his ‘immigrant’ status when he was transported from Africa to France (“I was a small hostile Beur, with an absurd attitude. I invented a country that never existed, a country on cardboard, instead of living the here and now”). “Beur is the term used to refer to a person born in France of North African immigrant parents. It is not a racist term and is often used by the media, anti-racist groups and second-generation North Africans themselves. The word itself originally came from the ‘verlan’ rendering of the word ‘arabe’” (Le Robert & Collins Dictionnaire Français-Anglais), where “verlan”, in the same dictionary, is “a particular kind of backsland […] [which] consists of inverting the syllables of words, and often then truncating the result to make a new word”. “border filmmaking tends to be accented by the ‘strategy of translation rather than representation’ (Hicks 1991, xxiii). Such a strategy undermines the distinction between autochthonous and alien cultures in the interest of promoting their interaction and intertextuality. As a result, the best of the border films are hybridized and experimental – characterized by multifocality, multilinguality, asynchronicity, critical distance, fragmented or multiple subjectivity, and transborder amphibolic characters – characters who might best be called ‘shifters’” (Naficy “Situating Accented Cinema”). Two boys spend their first years together, since Asmar’s mother is Azur’s wet-nurse and later his nanny. This mother-figure, a literally life-giving force for Azur who has never known his real mother, brings the two boys up with oral narratives from her homeland, in particular the tale of the Djinn Fairy who awaits the brave prince to overcome all obstacles and finally deliver her from an evil spell that keeps her imprisoned. The two boys, although later separated, are at some point reunited and set off together to achieve the liberation of the Djinn Fairy. Setting Dual displacement (temporal and spatial) Disorientation of this “in-between” or “beyond” state, neither here nor there, or both here and there at the same time “an exploratory, restless movement caught so well in the French rendition of the words au-delà – here and there, on all sides, fort/da, hither and thither, back and forth” (Homi Bhabha The Location of Culture). The Middle Ages, largely associated with a period of darkness for Western humanity, refer to a mediating period between the classical civilization of Antiquity and Modern times. The countries of the Maghreb, or Barbary Largely cast in the role of the enemy “The religion of its inhabitants alone was enough to exclude it from Christian Europe. The ambiguity of its position thus appears: part of the known world but irremediably alien, part of both Africa, the Mediterranean and the Islamic worlds. Hence the difficulty of deciding where to classify it, for each of these accepted divisions of the globe entailed a certain number of characteristics in the European imagination, which North Africa did not fit perfectly” (Ann Thomson Barbary and Enlightenment) Barbary: “a word which is overlaid with adverse connotations in European minds that it must immediately have provoked hostile reactions among most people”. “when an original culture is superimposed with a colonial or dominant culture through education, it produces a nervous condition of ambivalence, uncertainty, a blurring of cultural boundaries, inside and outside, a nervousness within” (Robert Young) Example: Poisoned by Saracen’s venom Azur (sky-blue French) Curse of blue eyes Motherless Wealth-poverty Asmar (dark Arabic) Curse of dark skin Fatherless Poverty-wealth Dominant position in the film Focal point in the opening sequence Breast-feeding (children’s nourishment) Children’s acquisition of speech Oral tradition “Only when we have considered the whole scope of the basic feminine functions – the giving of life, nourishment, warmth, and protection – can we understand why the Feminine occupies so central a position in human symbolism and from the very beginning bears the character of ‘greatness’” (Neumann The Great Mother). Primary Open Soft Good Other Unity Orient Secondary Closed Hard Evil Self Division Occident Crossing of the sea Africa Utopia Blindness Difference Divesting of previous identity Angel – Demon Angelic eyes – Evil eye Self – Other Native – Immigrant/Alien/Unwanted Sight – Blindness Wealth – Poverty Speech – Silence Familiar land – Unknown territory Bright – Dull Childhood stories – Frightful reality Beauty – Ugliness Example: Meeting between Azur and Asmar 1st merchant (addressing Azur): أنظر ماذا فعلت؟ )Azur: (Gives the merchant the money he earned from begging !عفوا ً أنا آسف )1st merchant: (takes the money ماذا تريدني أن أفعل بهذا؟ ماذا فعلت لربي كي أقع على صعلوق كهذا؟ 2nd merchant: !المسكين! لم يقصده 1st merchant: !لم يقصده؟ هؤالء الغرباء بدؤا أن يضايقوننا 2nd merchant: ) (Says something in a different languageوماذا عنك أنت؟ ألست غريباً؟ 1st merchant: !تكلم بالعربية و ليس بالقبائلية 1st merchant: “You miserable imbecile! Look what you’ve done!” Azur: “I’m sorry.” 1st merchant: “What do you want me to do with that? What have I done to good god to fall on such a cretin!” 2nd merchant: “He didn’t do it on purpose.” 1st merchant: “Not on purpose? They have started to annoy us, these foreigners!” 2nd merchant: “And you, you’re not a foreigner? (In Kabyle) Here, it is our home.” 1st merchant: “Speak Arabic, not Kabyle!”’ Deliberate absence of translation Gaps in understanding Sharing of alienation with main character Position of immigrant Exclusion “Translation becomes part of the process of domination, of achieving control, a violence carried out on the language, culture, and people being translated. The close links between colonization and translation begin not with acts of exchange, but of violence and appropriation, of ‘deterritorialization’” (Young). See Niranjana. ‘[…] The only drawback to this movie is that part of the conversation that is made in Arabic has no subtitle (fyi language used in the movie is French and Arabic but it has English subtitle).’ http://mettysays.blogspot.com/search?updatedmin=2007-0101T00%3A00%3A00%2B07%3A00&updatedmax=2008-0101T00%3A00%3A00%2B07%3A00&max-results=34 ; ‘The story was presented in French and Arabic and I found it a shame that they didn’t give subtitle for the Arabic dialogue’ http://whiteka.blogspot.com/2007_09_01_archive.html). Knowledge Inside/Outside Mediation No boundaries Power of the disempowered Example: Jénane / Princess Chamsous-Sabah Myth Utopia (all characters displaced/misfits) End of Film “the Other text is forever the exegetical horizon of difference, never the active agent of articulation. The Other is cited, quoted, framed, illuminated, encased in the short/reverse-shot strategy of a serial enlightenment. Narrative and the cultural politics of difference become the closed circle of interpretation. The Other loses its power to signify, to negate, to initiate its historic desire, to establish its own institutional and oppositional discourse. However impeccably the content of an ‘other’ culture may be known, however anti-ehtnocentrically it is represented, it is its location as the closure of grand theories, the demand that, in analytic terms, it be always the good object of knowledge, the docile body of difference, that reproduces a relation of domination and is the most serious indictment of the institutional powers of critical theory” (Bhabha) “If we must translate in order to emancipate and preserve cultural parts and to build linguistic bridges for present understandings and future thought, we must do so while attempting to respond ethically to each language’s contexts, intertexts, and intrinsic alterity. This dual responsibility may well describe an ethics of translation or, more modestly, the ethical at work in translation. […] Indeed, without more refined and sensitive cultural/linguistic translations and, above all, without an education that draws attention to the very act of translation and to the interwoven, problematic otherness that it confronts, our global world will be less hospitable; in fact, it could founder” (Bermann, Nation, Language and the Ethics of Translation)