Social Media and Social Change. Three different cases for different

Social media and social change

Three different cases for different outcomes: Tunisia, China and Italy

This paper analyzes the effects that social media have on the promotion of social change. Specifically, the research focuses on the role of social media as a tool to increase unification of communities towards stronger social capital, to open space for a new potential public sphere and ultimately to foster social change.

This work argues that the use of Internet has different effects in different cultures and societies. As a reflection of society, social media multiplies the effects of the people’s action and can even improve their connections and their social, and political power. Social media cannot, however, change the principles, features and goals of the society itself. If the society has a low level of social capital it’s not social media that is going to create it. If the legitimacy of a political regime is based on the popular support of its country social media will not change it. And if the democracy in a country is blocked by the ‘party politics’ social media will not create participatory democracy from scratch.

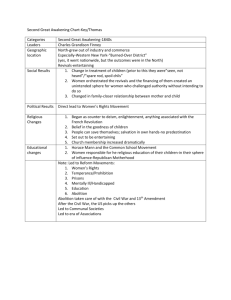

I try to demonstrate this with three different case studies: Tunisia, to see how is the situation now in the country that has been the sparking of Arab Spring; China, where national social media, often censored, don’t challenge (at least until now) the political system; and Italy, were social media have been the tools that brought the 5 Star Movement, a social movement guided by a comedian, into the Parliament.

This research is grounded by a theoretical framework integrating different points of view, drawing from the theories of Habermas, Castells, Hardt, Negri, Gerbaudo, as well as from specific concepts of social change, like the “propaganda of the seeds” and the “stigmergy” concept.

Social Change and social media: a brief literature review

Social change is something multidimensional and complex as it is made of many elements, different cycles and sometimes contradictory results, but is ultimately depending on both a change of mentality and a change of the structures of the society is its whole. The Hungarian philosopher, Arthur Koestler, argued in 1945 1 , that social change enforced only from inside, with cultural and personal transformation (as the

Yogi aims to do in his life) or only from outside, with a transformation of the political structure of the society (as the Commissar seeks to do) are both bound to fail. This happens because both elements are needed for a real social change: the individual and cultural change and the systemic and political change.

Antonio Gramsci 2 also affirmed that the struggle over ideas and believes (the ‘war of position’) had to go together with the revolutionary struggle (the ‘war of manoeuvre’) in order to succeed in the social change.

So both the reflection behind the action, in order to challenge the ideas of the status quo, and the action itself were both needed, according to Gramsci, for a real social change. Manuel Castells, the Spanish sociologist who forged the concept of modern network society , also wrote about this two elements: the

1 Koestler A. 1945. The Yogi and the Commissar. MacMillan.

2 Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers.

1

modern social movements as actors for cultural change (they can change the values of a society) and their

‘insurgent politics’ as actors for political change (they challenge the institutions for the adoptions of those new values) 3 .

If social change requests both change in ideas and structures than what does it come before or is anyway more important: the inner process and the cultural shift or the action at the base of the mobilization?

The emotional identification with a need for change or the realization of the triggering act that challenge the status quo? We can answer to this question in several ways. If we follow the ‘propaganda of the deed’ 4 , as Italian revolutionary Carlo Pisacane argued: “ideas spring from deeds and not the other way around” 5 .

Also Mikhail Bakunin, the famous Russian philosopher, wrote that “we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda” 6 . Often though the ‘propaganda of the deed’ has been associated with violent revolutionary acts of anarchist, and this sometimes jeopardized the important contributions she could have in the challenging of the status quo. At least until the XX century, when the Anarcho-pacifism 7 born and the propaganda of the deeds got closer to concept of Thoreau’s civil disobedience and Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance, with nonviolent actions and inner change as both important elements for social change 8 . Also others scholars explained the importance of the action in itself. Hannah Arendt for example affirmed the value of recuperating the Vita Activa of great deeds and great words in our modern age 9 . Finally according to the so called ‘ stigmergy’

concept, 10 social movements can benefit from the common action that derive from spontaneous collaboration 11 . Following these theories we could say that the deed, the action in itself, is what bring a real change, an authentic transformation of the society.

Before or besides the deed, nevertheless, the change of ideas and values has to happen, in both the minds and hearts of the people, if we want a change to succeed, as Madiba Mandela, Dr . King or Mahatma

Gandhi showed to the world during last century. These inspiring figures guided and drove an emotional shift, individually and collectively, that pushed their societies to pass from the fear , which block the people

3 Castells, M. 2009. Communication power. New York: Oxford University Press.

4 The ‘Propaganda of the deed’ is a political action that aim to be exemplary to others, usually associated with anarchism and its consequent violent political actions to challenge the status quo (regicides, assassinations etc.)

5 Pisacane, C. 1857. Political Testament. Also see Mann Roberts, R. 2010. Carlo Pisacane's La Rivoluzione: Revolution:

An Alternative Answer to the Italian Question. Matador.

6 Bakunin, M. 2002. Bakunin on Anarchism. Sam Dolgoff ed. Montréal: Black Rose Books. P195–6.

7 Anarcho-pacifism has been a form of anarchism and pacifism inspired by Tolstoj, Thoreau, Gandhi and others, that saw nonviolence as the only tool for social change, in particular before and during WWII. See Woodcock, G. 2004.

Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. University of Toronto Press

8 These concepts that have been used with success in many countries, from the ‘People Power Revolution’ in the

Philippines to the African-American civil rights movement

9 See on this: Wittkower D. 2012. The Vital Non-Action of Occupation, Offline and Online. International Review of

Information Ethics Vol. 18 (12/2012)

10 See: Elliott, M. A. 2007. Stigmergic Collaboration: A Theoretical Framework for Mass Collaboration. Centre for

Ideas, Victorian College of the Arts. The University of Melbourne. Also: Heylinghen F. 2007. Why is Open Access

Development so Successful? Stigmergic organization and the economics of information. To appear in: B. Lutterbeck,

M. Bärwolff & R. A. Gehring (eds.), Open Source Jahrbuch, Lehmanns Media

11 Stigmergy is a philosophical concept derived from insects’ life, which refers to a form of self-organization and collaboration of the masses without need for any planning or control.

2

and maintain the status quo, to the anger , that trigger the action in a process of risk-taking behavior 12 . As recent researches in neuroscience demonstrated (Damasio, 2009) 13 at its root individual or collective action is motivated emotionally and so we can say that also social movements are set in motion by emotional stimulus. For the triggering of social mobilization we need an emotional identification with the rest of the

‘imagined community’ as Benedict Anderson would say, a construction of ‘emotional coalescence’ (as

Paolo Gerbaudo 14 explained in his analyses of Arab Spring and Occupy Movement) a sharing of personal views and goals, that push for the action as expression of this emotion. So we may agree with Gladwell who said that “revolutions will not be tweeted” but not because, as he argues, new media activism are based on weak ties that are not enough powerful for social change 15 . The real reason is that revolutions grow in the belly of the population, before than in their mind, and so before to be tweeted need to be ‘felt’. We could argue than that the process of connection between hearts and minds stays at the base of the triggering act that challenge the status quo. There is not one that comes before or is more important than the other though, both the change in the mind of the people and the structure of the society are needed and crucial.

The question that comes to the mind now, in our modern and technologized societies, is what is the critical role of social media in this process of emotional identification and organized action? Can they help to create the humus for the emotional push of a common action or do they just reproduce a fragmented society helping in this way the maintenance of the status quo? It is difficult to answer these questions as scholars are still studying the effects of Internet and Social Network Sites (SNSs) on our societies but media philosophers agree that besides being technologies or ‘things’, SNS are also ‘concepts’, processes that transform our communication and influence the individual and social identity of the people. How they do it and with which results is still to be discovered, but drawing again from Castells, probably the most recognized scholar in media theory, we can say that the current social movements have as the most important common feature their ‘ culture of autonomy’ . Social movements create this culture of autonomy through the SNS, translating the so called ‘culture of individuation’ in the practice of autonomy. With an empowering process of re-learning how to live together as a community, social media play a fundamental role creating the conditions for a shared practice that help a movement to coordinate and act 16 . This has been the case for example of Arab Spring, where, supposedly leaderless movements were able to overthrown the regimes of their countries. Gerbaudo in his analyses of these revolutions and the modern social movements like Indignados and Occupy Wall Street, argued that social media, besides helping in the creation of the emotional humus, facilitate also what he calls a ‘choreographical’ leadership. This is a type of horizontal and ‘soft’ leadership that people share together in guiding and managing the social action 17 .

But independently by the fact that these movements had or not a leadership the reality is that social media had an enormous impact in their success and these two scholars helped us to understand it better, without going towards an optimistic and almost messianic view (like Clay Shirky). The limit of Castells or

Gerbaudo theories though is that they didn’t clearly ask if social media would have act in the same way in

12 For this concept of anger as trigger and fear as repressor see “The Affect Effect: Dynamics of Emotion in Political

Thinking and Behavior”, Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen, University of Chicago Press, 2007.

13 Damasio, A. 2009. Self comes to mind. Pantheon Books. New York.

14 Gerbaudo P., 2012. Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism. Pluto Press.

15 Gladwell, M. 2010. Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted. The New Yorker (2010, October 4)

Fom http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell

16 Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of outrage and hope: social movements in the Internet age. Cambridge: Polity

17 The process of mobilization according to the scholar is based on the notion of “assembling” and gathering rather than networking

3

other type of societies, if SNS could have had similar effect independently by the different cultures of the societies where they are used. This research think that is important to try to predict if their effect would be the same everywhere or they would depend on the community in which social media live and act, on the social fabric of that community and on its values, needs and goals.

The argument of this paper, adding a cultural approach and the researcher direct experience, is that social media are a social product and as such they empower and magnify the mental and political culture of the society in which they live, but they don’t change it, or create by themselves new values or new needs.

Surely social media are tools for a possible change as they facilitate mobilizations creating the emotional

‘coalescence’ and identity that can drive a revolution. We can even venture to say with scholars like

Diamond and Plattner 18 that social media can act as a ‘liberation technology’. But the argument of this paper is that we cannot think to social change as direct consequence of the use of social media. Social media cannot make a society think differently, change people’s mind creating a need that didn’t exist before (like for example a regime end) or create from scratch a new social capital in the society. What they can do is a process of “training citizenship”, opening space for the potential public sphere and empowering the people to become more active citizens, preparing them for future transitions towards more transparent and democratic systems. As they did in Tunisia and Egypt, after Ben Ali and Mubarak allowed populations to use them for years. As they are doing in China, even if the government is not using American social media but created its own, in order to control and not be controlled. And as they are trying to do in Italy, where a comedian led a movement of citizens to enter the Parliament thanks also to the Net. We will be back on the comparison of these cases in the second part of the paper but before let’s do a brief analysis on two specific concepts that are important in the process of social change: social capital and public sphere. How different cultures influence them and how social media affect them differently depending on the society in which they exist.

Social capital and public sphere: can social media create them?

Societies around the world as we know are generally culturally defined and roughly divided between either collectivist or individualistic societies. The first ones (often referred to more traditional societies in the Global South) emphasize especially group work, family ties and tend to have a higher level of social relations. The individualistic societies (often referred to Western developed countries) concentrate more on personal achievements and individual goals and tend to have less deep social connections.

Obviously this is a broad generalization that cannot be taken as absolute truth but as we know ‘culture matters’ as Weber but also others 19 taught us, and they have an impact on the type of development and social connections typical of that society. These general differences about the structure of the society across cultures (as well as similarities) are not static though but they change with time. If we take into consideration for example the “dimensions of culture” of the Dutch scholar Geert Hofstede 20 we see how the

18 Diamond L., Plattner M. 2012. Liberation technology. Social media and the struggle for democracy. Johns

Hopkins University Press.

19 See also : Huntington S., Harris L. 2001. Culture matters: how values shape human progress. Basic Books.

20 Hofstede utilizes six dimensions to compare cultures and analyze societies/organizations: Individualism-

Collectivism, Feminine-Masculine, Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Long-Short Term orientation and

Indulgence-Restraint. See Hofstede, G. Jan Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, McGraw-Hill USA, 2005

4

individualistic attitude in Western countries has increased in last decades. Hofstede argues in particular that in Western societies since the ‘60s we had a reduction of collaboration among people, diminishing the so called ‘social capital’ in civic, associational and political life, and this pushed these societies from

‘collectivist’ to more ‘individualist’ features. Social capital is a concept based on the value of social networks and became popular with the studies of Robert Putnam, who did researches in Italy (to see how social capital was making democracy work in some regions better than in others) and in US, arguing also that social capital was declining in America. It can be defined as “features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” 21 . Putnam in particular differentiated this concept between ‘bonding’ and ‘bridging’ type: the first is created when we socialize with people who are like us (same age, race, religion etc.) the second with people who are not like us (from different cultural groups for example, but also with different preferences or goals) 22 .

It is difficult to evaluate if mass media or even Internet had any role in this reduction of social capital in our Western societies since the 1960s. But we can ask if in our societies today social media help to increase or decrease it and if there are differences in influencing the two types of ‘bonding’ and ‘bridging’ social capital. This is still a debate among scholars even if there is a tendency to consider internet as leverage for more ‘bonding’ social capital, as it opens more spaces for networking with similar persons 23 , while there is not the same consensus regarding the impact on the ‘bridging’ type. Some authors argue that this type of social capital is not incremented but reduced by social media because their use reproduce the fragmentations and disaggregation of our societies. Cass Sunstein, an American legal scholar, worries about the risks for democracy of using Internet, because we tend to listen and speak only to the people with similar interests and values making us not used anymore to discuss different points of view 24 . A famous internet activist, Eli

Pariser, is concerned by the policies of the corporations owing the social media, which create often an online separation of interests reducing our openness to diversity (with the so called “Filter Bubble”) 25 . Other scholars nevertheless see also the bridging social capital increasing with social media (like showed in a research made on Facebook use in the American campuses 26 ).

The researcher makes an argument here (trying to demonstrate it with case studies) that this effect depend by the type of society in which social media are used, as they reflect the core values that are already in the society but don’t change them. So for example in societies that are more individualistic and tend to have less physical interaction or less social capital, like our modern Western societies, the empowering effect of social media is more about the individual purposes, related with personal interests, than the common interest, reproducing in a way or another the disaggregation of the society. In this way social

21 Putnam, Robert D. 1995. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 6: 65-78.

22 See: Putnam, Robert D., Lewis M. Feldstein, and Don Cohen. 2003. Better together: restoring the American

community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

23 Boase, Jeffrey and Barry Wellman. 2005. "Personal Relationships: On and Off the Internet." In Handbook of

Personal Relationships, edited by A. L. Vangelisti and D. Perlman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

24 Sunstein, Cass R. 2007. Republic.com 2.0. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

25 Pariser, Eli. 2012. The filter bubble: how the new personalized Web is changing what we read and how we think.

New York: Penguin Books. Parisier argues that the filter systems of social media, that control users’ preferences to make marketing moves, reduce exposure to different areas, points of views, interests, and, as a result, users become separated from what disagrees with their view, isolating them in their own cultural or ideological bubbles.

26 Ellison, N., Lampe, C., Steinfield, C., & Vitak, J. (2010). With a little help from my Friends: Social network sites and

social capital. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), The networked self: Identity, community and culture on social network sites

(pp. 124-145). New York: Routledge.

5

change is not so much promoted by social media as they cannot build from scratch social capital that doesn’t exist. In societies instead that are more prone to debate “on the streets” or societies where the solidarity of the community is a common value, like in the Mediterranean/Latin or the so called traditional societies 27 , social media tend to reproduce these connections, reinforcing them in a virtuous process of reciprocal influence and so also reinforcing the possibility of social change. We will be back on the concept of social capital with the Tunisia case but for now let’s see the possible influence of social media on another important concept for social change: the ‘public sphere’.

In order to understand the role of social media in influencing social change we have to understand also if in our globalized societies during the current information age there is a space for a real or at least potential ‘public sphere’ or not. Our modern Western societies have been described often as ‘liquid’

(Bauman) ‘networked’ (Castells) or even sometimes ‘inexistent’. Recently in fact there has been a philosophical and political critic to the concept of society as a united entity or a ‘commonality’, since

Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s claimed that “there is no such thing as society, but only individuals and families”. Many argued that this attempt to show the lack of a united society was a goal of neoliberalism since the 1980s, aiming to break the social cooperative relationships that could have represent a challenge to the liberalist status quo. The same view of disaggregated society, and of Internet reproducing it, can be seen also in many modern social scientists, even if not inspired by neoliberalist view, like in the analyses of Laclau’s ‘populism’ 28 , Latour’s ‘ANT theory’ 29 , the ‘multitude’ 30 concept of Hardt/Negri, the network society 31 of Castells or the ‘networked individualism’ of Wellman 32 . If we follow these concepts there is not much place for a potential ‘public sphere’, the sphere of social life where people of different ideas can come together to discuss common problems and influence political action. What is the role of social media in the creation of this ‘public sphere’ than, if they tend to reproduce the fragmentation already present in the society and even magnifying it?

Jurgen Habermas 33 , defining his famous concept of “public sphere”, argued that democracy improved with the birth of the bourgeois state because of the invention of the press and the creation of public spaces. Thanks to this people could debate and discuss social or political ideas similar to the situation in the ancient Greek Agora (the city square). But in reality the public sphere was not completely realized

(just as in the Agora ) as the press needed literate population to have its effect and cafes and theatres were frequented by high classes (usually white men) while working classes, women and minorities were still

27 See on traditional societies: Diamond J. 2012. The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional

Societies? Viking Edition. About the higher social capital in traditional societies see the work of Geertz, Malinovsky,

Mauss and the examples of communal work: African Ubuntu, Indonesian Gotong-royong, Philipino Bayanihan etc.

28 Laclau, E. 2005. On populist reason. London: Verso.

29 Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the social: an introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford University Press.

30 Hardt, M., and Negri, A. 2004. Multitude: war and democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: Penguin Press.

31 Castells M. 2004. The network society: a cross cultural perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Pub.

32 Wellman argues that today we live in horizontal individual networks (people together for specific purposes) rather than identity groups (based on class/religion/nationality etc.). This is not creating isolation but represents the declining of self-identity and action through hierarchical group’s identity towards more horizontal ‘preferential’ networks. Wellman, B. and Rainie, L. 2012. Networked: The New Social Operating System. The Mit Press.

33 Habermas, Jürgen. 1991. The structural transformation of the public sphere. MIT Press.

6

excluded from a possible ‘ res-publica’ (public thing). Antonio Gramsci 34 also talked about this concept, considering the civil society of 19 th and 20 th century as the public sphere where trade unions and political parties gained concessions from the bourgeois state (but also as the sphere in which ideas and beliefs were shaped and where bourgeois ‘hegemony’ was reproduced through the media, in order to ‘manufacture consent’ and legitimacy). Another famous scholar, Benedict Anderson, coined the concept of ‘imagined communities’ to refer to the new communities to which people imagined to belong with the birth of “print capitalism” 35 . These communities would have created according to Anderson a ‘public sphere’ using print technology and would have also be influenced by media that could target them addressing citizens as their

‘public’ 36 . Finally two contemporary scholars, Hardt and Negri 37 , suggested that today we should reconsider the distinction between public and private spheres as new technologies create new ways of communication and cooperation that give to the collective potentialities (the ‘new commons’) an important economic value.

Today, with the empowering potentiality of the new media, we could argue that while old mass media, being passive and uni-directed, had the risk of control over the masses, modern media, being instead multi-directed, have democratic potentialities. This not only as tools of communication and information

(‘from one to many’ and ‘from many to many’, as Castells would say 38 ) but as tools for the creation of a real ‘public sphere’, with new possibilities of political action and civic engagement (as Diana Saco and others scholars argued with ‘cybering democracy’, ‘digital citizenship’ and ‘private sphere’ 39 ). We could agree with these theories because social media today have an important role in ‘training’ people as we said, in particular youth, to express their ideas and making them more active citizens. We will see that potentiality in all our three case studies. But there are two major limits in the use of Internet that make the concept of public sphere still something ideal more than something completely realized (just as it was with the old media). These two limits are the digital divide and the network surveillance exercised also on the new media. Regarding the first, the use of the new media follow the same concept of inclusion and exclusion and the same access and usage inequality of the old public spheres. Who has no access to Internet, i.e. people living in areas that are not connected, or who don’t have the technical skills to use it, is obviously excluded from this new ‘virtual sphere’, as Norris 40 and Papacharissi first argued 41 . The second reason that still keep public sphere as a potentiality not completely realized comes from the fact that communication is

34 Heywood, A. (1994) Political Ideas and Concepts: An Introduction. Macmillan.

35 Anderson introduced this concept to explain that with the birth of printing, capitalist entrepreneurs printed books and media in the vernacular (instead of exclusive script languages, such as Latin) in order to maximize circulation and so created the imagined community of nationality, not existing before.

36 Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. NYC: Verso.

According to Anderson’s definition ‘Imagined communities’ are not based on everyday face-to-face interaction between its members, so similarly we could define also social media communities as imagined communities.

37 Hardt, M., and Negri, A. 2004. Multitude: war and democracy in the Age of Empire. Penguin Press.

38 Castells, M. 2009.

39 See: Saco, D. 2002. Cybering democracy: public space and the Internet. Electronic mediations: v. 7 Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press. Also : Karen Mossberger, Caroline J. Tolbert, and Ramona S. McNeal. 2008. Digital

citizenship: the internet, society, and participation. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. And: Papacharissi, Z. 2010. A private

sphere: democracy in a digital age. Cambridge, UK; Malden, USA. Papacharissi defines the ‘private sphere’ as a sphere facilitated by new technologies, that even if is not a direct recipe for more democracy is an attempt to create new spaces and new sociality, useful for democracy.

40 Norris Pippa. 2001. Digital Divide? Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge

University Press.

41 Papacharissi, Z. 2002. The virtual sphere. The internet as a public sphere. From New Media and Society n. 4, 9-27

7

a sharing and a construction of meanings, and so it is an exercise of power 42 . As a consequence who control the communication can exercise an enormous power on the public opinion (this has been the case since the concept of Fourth Estate and the power of influence of mass media). We could argue that with the

Information Age the power structure can be also reversed, because information is more accessible and transparent and so the ordinary people can even “control the controller” (as the cases of “leaking” secret information in USA demonstrated). The problem though is that social media are privately owned by big corporations with a great economic and political power that goes against the common good they want to represent. So, even if the ‘big brother’ dystopian view of Orwell seems far from reality, the fact that the nature of most Western social media is commercial (that means with the goal of profit) and the fact that the private information is monitored by governments, challenge the ‘freedom potentiality’ of social media and the possibility to build a real public sphere (as Morozov argues in his famous book The net delusion 43 ).

Obviously in the authoritarian regimes is even worst as Internet is completely in the hands of the governments (like in the Chinese case that some scholars define as ‘networked authoritarianism’ 44 ) living few possibilities out of the control and the censorship.

So in conclusion this paper argue that even if the network society allows the people to participate to the creation of the meanings around their personal values and propositions (and not only around the values and proposition of the system) the public sphere is something still far from being completely realized even with social media. As well as the social capital is not something that can born only with the presence of social media (even if they can help to increase his presence) as it needs a culture based on collaboration and solidarity more than fragmentation and invidualism in order to exist. So if social media, as every media, reproduce the exclusions already present in the society or the inclusion and social capital of the community, but cannot radically change them, what are the consequences of their use? The consequences are that if post-modern Western societies are liquid and disaggregated they will maintain and possibly expand this fragmentation. If Western societies are more individualistic than the Eastern ones they will not increase their social bonds only because of the use of social media. As well as if a country has no politicization of the people against the regime or not much social capital in its fabric social media will not create this political request or the structural change in that society. At the same time though social media will increase the

‘possibility’ of creating a public sphere, not building it directly but opening a space for it and training the citizens to a more complete civic sense. Meanwhile this could improve indirectly also the social capital if already present, because to be more active in the society means to create more solidarity with the community, as the social action cannot be only individual but needs networks and connections. Therefore social media cannot build social capital or public sphere by themselves but they can facilitate their construction by the people, so indirectly influencing also a real social change. This is their role and this is what they have been doing until now. And if we look at the results around the world, from Tunisia to China and to Italy, it seems that they are making it quite good.

42 Castells, the most famous scholar of media and power of communication, defines communication as “the sharing of meaning through the exchange of information” (Castells, 2009, p54) and power as “exercised by means of coercion (or the possibility of it) and/or by construction of meaning” (idem, p10). Castells, M. 2009.

43 Morozov, E. 2012. The net delusion. The dark side of Internet freedom. Public Affairs.

44 MacKinnon R. 2012. China’s networked authoritarianism. In Diamond L., Plattner M. 2012. Liberation

technology. Social media and the struggle for democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press.

8

Tunisia today: social media increasing social capital?

Tunisia has been the center of world attention, for what later would have been known as the Arab

Spring, since the end of 2010. The revolutions of Arab Spring, as we know, have been defined at the beginning as the ‘social media revolutions’, while with some deeper analysis we realized that even if social media ‘fostered’ the revolutions or even ‘facilitated’ their organization they didn’t ‘make’ them. The revolution in Tunisia was pushed by the needs of the young people that had their two slogans in the words

Karama (dignity) and Hurria (freedom), the two rights that were missing in their life. The revolution was caused by the economic crisis, which made impossible the life of the youth, especially the college graduates that remained unemployed for years and decided finally to lead a revolt (replacing the traditional leadership as the driving force). The revolution was made by the actions of occupying the squares and facing the repression (as the ‘propaganda of the deeds’ or Harendt would have predict) but at the same time also by the ‘mental change’ needed to pass from the fear to the anger (Neuman and MacKuen, 2007). And finally the revolution was also helped by the strong cyberactivism culture of the youth, who was able to criticize the regime for several years, and by a relatively high diffusion of Internet in the Tunisian society respect to other Arab or African countries (Castells, 2012). It was helped by social media both in the process of

‘emotional coalescence’ and in the creation of a ‘choreographical’ leadership, allowing a traditional society based on hierarchical leaderships to use instead a horizontal leadership to topple down the regime

(Gerbaudo, 2012). So we can say that social media in the case of Tunisian revolution played a quite important role, but they didn’t cause or made the revolution: the revolution was caused by the need of a regime change felt by the population (in particular the youth part) and realized thanks to the strong social bonds present in the society, that pushed the youth to connect and become a force of change.

This short chapter is not focusing however neither on the use of social media during the revolution, as many scholars already analyzed it nor on the role of social media in the democratic transition in Tunisia after the revolution (even if it would be interesting given the good results of this transition, at least respect to other countries of the Arab Spring). This chapter analyzes the possible uses of social media in Tunisia today, in particular in the rural areas of the country where the revolution started. The researcher is interested in seeing how the youth population is using today the social media, which is the level of social capital that they have in their community, and what is the role of social media in empowering their civic sense and citizenship. This taking the case of Menzel Bouzaiene as an emblematic example that the researcher know directly, having studied this case for few weeks in Tunisia during the summer of 2013.

The Tunisian youth of rural areas represent a big part of the population that is still cut out of the modern technological revolution. These remote provincial areas didn’t participate much in the past to the exchange of information and communication as they didn’t have neither the infrastructure nor the human capital to do it (access and usage exclusion were both present, as Papacharissi would say). But it is exactly in these areas that the revolution started and spread to all Tunisia because these were the places most affected by the economic and social problems. In particular the town of Menzel Bouzaiene, in the Sidi

Bouzid region, was cut out from the Internet until 2010 and its socio-economic situation before the revolution was quite disastrous: in 2010 the unemployment rate was more than 40% and the illiteracy rate more than 70%. After the revolution this situation didn’t change much, being this area still one of the poorest regions of Tunisia. What changed though was the ability of part of its population to have access to

9

the outside environment, gathering and sharing information with the rest of Tunisia and the rest of the world, because of the new connectivity of the region .

In 2010 the majority of the families were deprived from the use of the Internet in education and work (only 1% of the families had a computer at that time) while today 45 20% of the houses in Menzel Bouzaiene are connected with Internet, there are 20 ‘Publinet’ or Internet Cafes (out of 170 in the whole country) and the youth of the region is finally in contact with the rest of the world.

But how the youth of this region is using now Internet and what is the role of social media in training their skills of digital citizenship and reinforce their potential for social change? A local NGO called

ACCUN ( Association for Digital Citizenship and Culture ) played an important part in the digital and civic development of the area. This organization, born soon after the revolution following expressly the

‘stigmergy’ philosophy of action, aims to disseminate the digital culture among the youth and strengthen their participation in the local governance. To do this, a part using a web site and a center for the digital operations, this association focus on organizing trainings about citizen, civic, community and collaborative journalism, in particular with the creation of video clips and web sites.

46 Many people know already that

‘citizen journalism’ is a journalism in which common citizens collect, analyze and report news and information but not many people may know the meaning of the other types of journalism. ‘Community journalism’ is the coverage of our local communities, our neighborhoods or even our small towns; the ‘civic journalism’ imply a democratic process as media not only inform but aim to engage citizens in public debates; and finally ‘collaborative journalism’ requires that more reporters contribute to a news story together. So with ACCUN young people of Menzel Bouzaiene started to experiment all these type of journalism, as together they became citizen journalists, discussing their problems, increasing the local awareness and bringing their demands to the local administrators. In three years the youth of the village cooperated in many projects, helping each other’s in the realization of videos for community purposes, organizing Hacker festival or filling political petitions (and even creating a communal radio for the citizens). This was possible, like in the revolution, also because of the propensity of the people to collaborate, more than compete, among themselves and to create connections inside and outside their personal groups. In few words to ‘build a stronger social capital’, something already present in Tunisian society, as in mostly of the Mediterranean societies, but something that still have the potentiality to grow.

Therefore looking at the example of the youth of Menzel Bouzaienne we can say that as the use of social media was functional in the Tunisian revolution a new use of it is now functional in the empowerment of rural youth. Social media are increasing both the bonding type of social capital (Boase, Wellman, 2005) with the empowerment of groups already formed and the bridging one (Ellison, Lampe, Steinfield and

Vitak, 2010) with the creation of new groups with different interests but looking at common actions for common goals. This process shows how social media can magnify what it is already in a society, like a good level of social capital as in the Tunisian rural society, that is a society not fragmented but rather united

(the polarization between secular and Islamists is more present in the urban areas for example). And it also demonstrates how social media and social capital are interconnected in a virtuous relation of reciprocal influence in which the expansion of one increase in turn also the expansion of the other.

45 http://www.sidibouzidnews.org/menzel-bouzaiane-village-connecte/

46 One interesting project for example, funded with the help of an Italian NGOs, is called “Peripherie Active”. It supports local civil society in its ability to do networking for the inclusion of the demands of vulnerable population.

See on this: https://www.facebook.com/pages/P%C3%A9riph%C3%A9rie-Active-Accun-Gvc-Ya-Bastaue-

TUNISIE/292845414076651

10

So, as we see, not every society use social media in the same way but every society can make of them the best use if they want, that means making them functional to their needs and useful to their actions.

This is what Tunisian rural young society has been doing and this is what youth of other societies have also done with social media. Let’s see now the Chinese case and how the new media affected the creation of another important element for social change: the potential public sphere.

China today: social media opening space for a potential public sphere?

The reflections we do in the Western world about social media and social movements in China are often associated with censorship, repression and lack of freedom. China is one of the five countries on

Reporters without Borders’ list of “State Enemies of the Internet” 47 in 2013 and China’s “Great Firewall” 48 is probably the best repression system in the world for controlling Internet users. Nevertheless, even if the use of SNS for mobilizations purposes is clearly limited by the state, there are possibilities for the netizens to go around censorship and filters, like the use of “social steganography” 49 or the substitution of banned characters with others that have unrelated meanings but sound alike or look similar (thanks to the Chinese language that offers these possible evasions) 50 . The problem though is that, beside the repression, China is using another intelligent way to control communication, in order to avoid the so called “dictator’s” or

“conservative” dilemma 51 . According to this dilemma if a government shuts down Internet access it would obviously risk radicalizing citizens’ attitude or harming the economy. As Zuckerman’s Cute Cat theory

52 argues too, it is dangerous to block a platform broadly used for enjoyment communication (that is also usually used for political activism) as people will protest, trying to find a way to have their ‘cute cats’ (since

Latin time: panem et circenses ). How did China solve these problems? They created their own social media:

Weibo, Renren, and Youku , that are the alternative platforms to the Americans Twitter, Facebook and

YouTube. Chinese government didn’t block social media like Mubarak or Ben Ali, instead it created alternative ones, in order to allow the networking and enjoyment but limit their use in social and political movements (as the servers are in China and so can be controlled). This short chapter doesn’t analyze however the level of surveillance in China, also given the fact that the 2013 ‘mass surveillance disclosures’ made by Edward Snowden, showed how Western surveillance might be not so different, at least in its effects, from the actions of China’s SkyNet team (the Chinese Internet police). The chapter instead analyzes

47 China, Syria, Iran and North Korea have their governments involved in intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information. From: http://surveillance.rsf.org/en/china/

48 Great Firewall of China is a project operated by the Ministry of Public Security division of the government of China, which began operations in November 2003. Beside the normal control of IP addresses or domain name it makes large-scale use of Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) to block access based on keyword detection.

49 Social stenography (hiding information creating a message that cannot be understood) is used on the web to post events with different images respect to the originals without explanation so they can get through the filters. See: http://www.buzzfeed.com/kevintang/how-the-chinese-internet-remembers-tiananmen-on-its-24th-ann

50 See on this: How to get censored on China’s Twitter, ProPublica, 11/14/2013. From: http://www.propublica.org/article/how-to-get-censored-on-chinas-twitter

51 This dilemma is defined by the media theorist Asa Briggs : if a government shut down Internet access or ban cell phones it would risk radicalizing otherwise pro-regime citizens or harming the economy. See: Shirky, C. 2011. The

political power of social media: technology, the public sphere and political change. Foreign Affairs, Jan/Feb 2011.

52 Cute Cat theory (“cute cats” is used for any low-value but popular online activity) was developed by Ethan

Zuckerman in 2008. From: http://www.ethanzuckerman.com/blog/2008/03/08/the-cute-cat-theory-talk-at-etech/

11

how social media reproduce values and needs of the Chinese society and multiply the actions already present inside this society, with the possible effects on the creation of a new potential public sphere.

Unfortunately there are not many books written by Chinese scholars on these topics but one of the exceptions is a recent book 53 on how Web 2.0 influence civil society and its demands in East Asia. In the chapter on China the author, Hu Yong 54 , argues how China’s “harmonious society” is living a more or less socially stable period since the repression of Tiananmen in 1989 and the reasons are similar to the ones that maintain stability in Western developed democracies: economic security and political legitimacy. But probably social media are opening a new space for a ‘virtual sphere’ where some sort of protest culture and freedom of assembly could be revitalized again, as the Internet allowed Chinese netizens to become what has been defined “the biggest NGO in the world” 55 . The blogger Michael Anti for example argues that the

“Chinese bloggers are in fact creating the first national public sphere in the country’s history” 56 . We don’t have much statistics on the Internet users (gender, class, ethnicity etc.) to see if this is something even close to a potential public sphere but the mere fact of having 300 million microbloggers using Weibo in China today, is really something significant. But is this what Papacharissi would call “private sphere”, that increase participation and sociality, what Hardt and Negri define “new commons”, with collective potentialities and economic value, or what Castells would call networked society, with multidirected communication and the potentiality to empower democracy? May be, but it is important to know deeply a society, with its culture and its history, before to analyze what a new form of media can bring to the traditional organization and values of that society.

The mobilization that accompanied the booming of social media in China for example has been defined mostly as a local “ordinary resistance” 57 instead of a global “dissident resistance” (that is more confrontational with the political system). There are many cases of bloggers increasing awareness on local issues through Weibo but not many confronting the regime. Is this because who does it go directly to jail, as the few that did it already? Could be, but maybe there are other reasons too that we can analyze if we look at the history of social demands in China. In fact, in the past, the petitioner system was the Chinese system that allowed the citizens to do requests to their government, who had to hear complaints and grievances from the citizens. Today the petitioner system is living a new phase with Internet, as there are in China millions of individual actions of petition that go to the central government against social injustice, and these actions are also spread in the local and national communities thanks to Internet and microblogging. In this way the isolated cases of protests are transformed in public events and this is good for the public support but at the same time is also functional to the Chinese government (as the old petition system , with many people going to Beijing to bring their demands, would have create a high risk of demonstrations in the capital). So as noted by Yiyi Lu 58 these online actions allow protesters to reach the

53 Ip Iam Chong, 2011. “Social Media Uprising in Chinese-speaking world”, Kindle version

54 Professor at Peking University's School of Journalism and Communication

55 The number of netizens in China was 457 million in 2010. See “The 27th Statistical Report on the Development of

Chinese Internet.” China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). 01/19/11.

56 From http://www.ted.com/talks/michael_anti_behind_the_great_firewall_of_china.html

57 One example are the anticorruption protests after the earthquake in Sichuan in 2008. “Ordinary resistance” can be defined as “small, localized and isolated cases that lack ideological and organizational affiliations required for linking them together”. See: Perry, E. J. and Selden, M. 2003. “Introduction: Reform and Resistance in Contemporary

China.” Chinese Society, Change, Conflict and Resistance, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge Curzon. P. 17

58 Lu, Yiyi. 2010. “Chinese Protest in the Age of the Internet.” China Real Time Report. The Wall Street Journal, 14

Dec. 2010. From: http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2010/12/14/chinese-protest-in-the-age-of-the-internet

12

local authorities and at the same time be successful in obtaining their goals, through gathering public support online instead of in the streets. This is also possible because the servers of social media are in Bejing so the local authorities cannot track the data of the local microbloggers (the risk of big brother dread by

Morozov is constrained in this case thanks to a decentralized use of social media and a centralized control).

These actions of ‘online petitions’, even though have not a real sense of political dissidence and probably cannot be transformed in large-scale social movements, nevertheless have the power to shake public opinion on local issues, increasing the debate on political questions, and this is what Internet can do in China right now. It can create a virtual space not for a potential regime change (at least for now) but for a potential public sphere, as imagined by Habermas, in which people debate on common issues and propose common solutions. This is also what Xiao Qiang (founder of China Digital Times ) believe is happening in

China today: the creation of a ‘popular opinion’ with the rise of an autonomous ‘quasi-public space’ where social and political questions can be discussed 59 .

This shows also how social media reflects the values of a society: if the Chinese society still accept to have a one party system because their cultural interpretation of democracy is different from Western societies or because of their nationalism and Confucian values or because of any other reason, this will not be changed by an internet tool. Until there will be not enough need of political change in the population the kind of “dissident resistance” will remain sporadic, while the “ordinary resistance” will keep growing. This will help to start probably a new phase for Chinese public opinion and social mobilization. So, presumably, the future of China’s transition will not be a revolutionary regime change like in Arab Spring on in Eastern

Europe, but a more conscious gradual transition towards making the people’s voice more heard through the new channels in the long run 60 . At least until another demonstration like Tiananmen Square protests will tell us the opposite.

Italy today: social media facilitating participatory democracy?

The freedom of the press in Italy is the lowest of the Western Europe, also because of the 20 years of the Berlusconi era, affected by the media tycoon that controlled the majority of the public and private media in Italy. In its 2013 report, Freedom House listed Italy still as “partly free” country and ranked the nation 68 th in the world together with Guyana. Nevertheless, and probably because of that, the social media use is on the rise: in 2012 the percentage of population using Facebook in Italy raised to 40% 61 while the number of Internet users was around 60% 62 and 60% of the families had a personal computer 63 . Who understood well and early the importance of Internet penetration in the formation of Italian public opinion has been a comedian, Beppe Grillo, who started in 2005 a social-political movement through the use of local Meetups (following the 2003 campaign for the primaries of the Democratic Party in the US). Today his movement, the 5 Star Movement (5SM), is probably the most powerful social-political movement in the world born on the Internet platform .

Following the Arab Spring in North Africa and Occupy movement in the US, the 5SM became in 2013 one of the three main political parties in Italian parliament, reaching

59 Diamond L., Plattner M. 2012. Liberation technology. Social media and the struggle for democracy. JHU Press.

60 See on this Clay Shirky, 2011. The political power of social media: technology, the public sphere and political

change. Foreign Affairs, Jan/Feb 2011.

61 From: http://businessculture.org/southern-europe/business-culture-in-italy/social-media-guide-for-italy/

62 From : International Telecommunications Union, 2012.

63 From : National Institute of Statistics, 2012.

13

its goal of de-stabilize the party-based status quo. For this they used a new (even if old too) way of social and political change: start with demonstrations and protests but then go to politics, build a ‘party’ and enter the national Parliament with officially elected citizens, using mostly Internet propaganda and organization.

How did they arrive at this point only with a blog, a famous comedian leading them and an economic crisis that found in the vote of protest, instead of a rebellion, his way out?

First of all we need to explain something more about the 5SM. This is an environmentalist,

Eurosceptic, antiestablishment ‘party-movement’ that advocates for more participatory democracy trying to destroy the partitocracy (a term that indicate in Italian the hijacking of institutions by the party politics) and give power again to the citizens (not only sending some of them directly to the parliament but making them participating to the online proposition of the new laws). This is a new thing in Italian politics but is still tied to the ability to use Internet and to the interest of the population to participate to the legislation, that not always is present, in particular in the old Italian population. The 5SM refuses the title of political party has it doesn’t have a party structure and its founder and president is not a professional politician but a comedian that guide the elected from his home and his blog. Beppe Grillo for many years conducted his shows against bad politics and politicians in the theaters of Italy and finally entered in politics when he met

Gianroberto Casaleggio, an online marketing expert who believed in the ‘Internet centrism’, to say it with

Morozov. Grillo and Casaleggio are today accused of populism, extremism and lack of internal democracy in the party and probably they are right criticisms 64 . But this short final chapter will not analyze the politics behind this ‘party-movement’, looking instead at how the 5SM used the Italian social fabric and the communication power of the net to reach this level of power. The question to ask in the Italian case is: how the Italian social capital and the use of the social media, affected the evolution of the 5SM? Obviously without the social, political, economic and moral crisis that lived Italy in the last 20 years the 5SM could not reach this level of support from the population, but the researcher believes that the presence of social capital in the Italian community, and the potential public sphere created with the blog and the Meetups, represented two important elements on this path.

The core of the 5SM is represented by a network of motivated activists and citizens who worked for many years on popular causes like anti-nuclear campaigns, renewable energy, cuts to the political costs etc. These activists often were coming also from experiences in local cooperatives and associations of citizenship and civic engagements. These are the typical organizations of Italian society (the type of networks that Putnam defined as the base of social capital 65 ) in particular in the center and north of the peninsula, where solidarity helped the creation of mutual aid associations and cooperatives. Unfortunately the political parties could not answer to their demands, apart from the Communist Party that functioned often as the sounding board of their requests but who had been almost always out of the national governments. What Grillo and Casaleggio did than was to use the presence of these local political activism and channelize it through the use of Internet. This activism was already present in the social fabric of Italy

64 Also given the fact that Grillo and Casaleggio are the only guides of the party-movement and the more than one thousand Meetups are not much democratic as are guided by who founded them and pay for them every month.

See on this the analysis of Giovanni Tiso : Tiso, G. The net will save us. Overland. Winter2013, Issue 211, p55-60.

65 See on this: Putnam, R. 1993. Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press.

Putnam explains how the lack of social capital in the south of Italy and its presence in the north made the new regional institutions to have different levels of efficiency and so different level of democracy.

14

and this is why a party-movement like 5SM could growth in short time as it could take the strength of the national social capital and put it at the service of a high value that is the administration of the country.

The other element that helped the party-movement to reach this success has been the internet, which became the tool that the citizens used to protest against the authoritarianism of Berlusconi for several years.

The Internet was the powerful instrument that 5SM used as a platform in which the people met, organized and discussed before local, and then national, political propositions. For example the proposition of a new electoral law, that Italy waited since long time, has been draft during few days in the spring of 2014 by the members of the 5SM (people that have simply registered online since at least one year) that were in total around 50 thousand people, still a small group if compared with the entire population of the country but a fair amount of people if we consider that this type of laws usually are draft by a very small group of experts.

The voters were guided by explanations of the different choices and they build the text of the law step by step all together online. So the blog of the 5SM represented in this case a tool for legislation, not only a tool for election or campaign. The web than can be considered the fundamental medium for this ‘partymovement’, and represent a potential public sphere not only for the most engaged activists of the 5SM, but for everyone that have a connection, time, interest and some ability to use the computer. Obviously besides the virtual public sphere, as we said earlier, also the physical public sphere is important in a party that wants to mobilize the population not only to vote but to actively participate, and the face to face contact represents a basic glue that reinforce the groups for common actions. This is why the Meetups were so crucial, representing open spaces where even if the hierarchy was still present everyone could participate, to “have fun, get together and share ideas and proposals for a better world, starting from their own city” 66 .

Finally we have to say that obviously to get 25% of the votes we need to involve a much broader public than just a community of activists and engaged netizens , in particular in a country where the population is quite old and not always used to the use of Internet. For this reason the role of Grillo, the comedian that was able to gather dozens of thousands of people during his speeches in the Italian squares, was fundamental in order to spread the new message and the desire to de-stabilize the establishment to a wide audience. So we can say that social media and Internet played a very important role in the organization and participation of the people to the ‘party-movement’, even if the potential public sphere would have not been enough without the social capital, already present since long time in the Italian society.

67 We don’t know what will be the future of Italy in this transition after 20 years of Berlusconism . The center-left

Democratic Party understood that had to pass a complete renovation besides to accept to still govern with

Berlusconi’s party if they wanted to avoid the destruction of the 5SM. The party chose a young president,

Matteo Renzi, the mayor of Florence, a 39 years old smart and photogenic heir of the old Christian

Democracy, who became the new Italian Prime Minister in 2014. The future of Italian democracy is not clear but one thing is certain: the Italian politics are not the same anymore as the old parties had to accept more participation from the citizens and more transparency in their actions, because a party-movement, born inside the Italian social capital and grown on the online public sphere, has changed the approach to democracy in Italy. And this will benefit not only Italy but the representative democracy in general.

Conclusions

66 Beppe grillo interviewed in Grillini in movimento – Micromega online. 04/20/2012.

67 Hartleb, F. 2013. Anti-elitist cyber parties. Journal of Public Affairs. Nov2013, Vol. 13 Issue 4, p355-369.

15

In this paper the researcher attempted to show how social media can influence social change facilitating the creation of a potential public sphere and reinforcing the level of social capital. This work also analyzed how different societies, with their diverse features and values, influence the use of social media for their own purposes. The results in the comparative analysis are that social change happens (either through a revolution or an electoral process) if the society is ripe for that change. Social media can help in opening a potential public sphere, strengthening the level of social capital and increasing political activism to promote change. Social media act as tool for training citizenship but they are not able to change the needs, goals and desires of a population. They cannot challenge the status quo unless this it is a real need of the people. So we cannot directly transfer their effects from a society to another one: Arab Spring was a peculiar phenomenon as 5SM or the petitioning system. The use of social media is a reflection of the society not the other way around. Technology can influence society but not completely revolutionize it.

As we saw the direct action and the ‘emotional coalescence’ behind it are important factors in social change even if social media don’t create them by themselves. If a society is politicized and people demonstrate on the street for a change, the time spent behind a screen will complement and sometimes even reinforce the actual time passed physically together, like during Arab Spring. If a society is not politicized or present its demand in a different way to the government (like the case of petitioner system in China) social media will not change it bringing the people to the streets or making them opposing the regime, but they will reinforce and empower in some way the political and social requests of the people. Finally if a society is politicized but exhausted by the partiality of traditional media and the lack of participatory democracy, like in Italy, the communities can find in the new social media a way to express their strong social capital and increase the direct participation in the political arena.

If we compare Arab Spring, China status quo and Italy ‘online party-movement’, we see how social media had, at least until now, different effects, not only because of the different control, censorship or access to the Internet, but because of the of the peculiar situation in the different societies, their different cultures and economic situations and their different level of social capital. Social media open space for a real change only if that is already a request of the population. They can help in redirecting social capital towards more concrete actions like blogging, citizen journalism or even an ‘online party movement’ only if the social capital is already there. And social media can also expand the possible public sphere of every society (like Hardt, Negri, Papacharissi and Castells argue) allowing citizens to train in debate and selfexpression, and so empowering them in a process of autonomyzation and new narration. But every society has different use of that potential public sphere, and if a society use it for a revolution, or a more gradual expression of grievances, or the creation of an ‘online party-movement’, this depend by the society itself.

Social media can potentiate and magnify citizens’ needs and demands, even if they cannot change them. Like printing led us to a more democratic modernity, the Internet is guiding us to a more democratic post-modernity, and this can increase our freedom and empower our society. Whatever type of society is and whatever definition of democracy has.

16

REFERENCES

-Aaker, Jennifer Lynn, Andy Smith, and Carlye Adler. 2010. The dragonfly effect: quick, effective, and powerful ways to use social media to drive social change . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism .

NYC: Verso.

Bakunin, M. 2002. Bakunin on Anarchism . Sam Dolgoff ed. Montréal: Black Rose Books. P195–6.

Boase, J. and Wellman, B. 2005. Personal Relationships: On and Off the Internet. In Handbook of

Personal Relationships, ed. by A. L. Vangelisti and D. Perlman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-Castells, Manuel. 2009. Communication Power . NYC: Oxford University Press.

Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of outrage and hope: social movements in the Internet age.

Cambridge:

Polity.

Damasio, A. 2009. Self comes to mind . NYC: Pantheon Books.

Diamond, J. 2012. The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? Viking

Edition

-Diamond, Larry Jay, and Marc F. Plattner. 2012. Liberation technology: social media and the struggle for democracy . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

-Earl, Jennifer, and Katrina Kimport. 2011. Digitally enabled social change: activism in the Internet age .

Acting with technology: Cambridge: MIT Press.

-Elliot, M.A. 2007. Stigmergic Collaboration: A Theoretical Framework for Mass Collaboration.

PhD

Thesis. University of Melbourne.

- Ellison, N., Lampe, C., Steinfield, C., & Vitak, J. (2010). With a little help from my Friends: Social network sites and social capital.

In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), The networked self: Identity, community and culture on social network sites (pp. 124-145). NYC: Routledge.

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2012. Tweets and the Streets . NYC: Pluto Press.

Gladwell, M. 2010. Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted . The New Yorker (10/4/2010)

Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks . International Publishers.

- Habermas, J. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere . 1991. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hands, J. 2011. @ is for activism: dissent, resistance and rebellion in a digital culture. NYC: Pluto Press.

-Hardt, M., and Negri, A. 2004. Multitude: war and democracy in the Age of Empire. NYC: Penguin Press.

17

- Heylinghen, F. 2007. Why is Open Access Development so Successful? Stigmergic organization and the economics of information . To appear in: B. Lutterbeck, M. Bärwolff & R. A. Gehring (eds.), Open Source

Jahrbuch, Lehmanns Media.

Heywood, A. 1994. Political Ideas and Concepts: An Introduction . Macmillan.

Hofstede, G. 2005 Jan Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind . McGraw-Hill.

Huntington, S., Harris L. 2001. Culture matters: how values shape human progress. Basic Books.

- Joseph, Sarah. 2012. Social media, political change and human rights . Boston College Law School.

Karen Mossberger, Caroline J. Tolbert, and Ramona S. McNeal. 2008. Digital citizenship: the internet, society, and participation. Cambridge: MIT Press

-Koestler A. 1967. The Yogi and the Commissar . MacMillan.

Laclau, E. 2005. On populist reason. London: Verso.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the social: an introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford Univ. Press

-Lovink, G. and Rusch M. 2013. Unlike us.

Inc Reader n. 8. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

-Mattoni, A. 2012. Media practices and protest politics. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2012.

-Morozov, E. 2012. The net delusion. The dark side of Internet freedom. Public Affairs.

- Mossberger, Karen, Caroline J. Tolbert, and Ramona S. McNeal. 2008. Digital citizenship: the internet, society, and participation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

-Norris Pippa. 2001. Digital Divide? Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide .

Cambridge University Press.

-Papacharissi, Z. 2002. The virtual sphere. The internet as a public sphere. From New Media and Society

4 (2002) 9-27.

-Papacharissi, Z. 2010. A private sphere: democracy in a digital age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Pariser, Eli. 2012. The filter bubble. NYC: Penguin Books.

-Pisacane, C. 1857. Political Testament . Also see Mann Roberts, R. 2010. Carlo Pisacane's La Rivoluzione:

Revolution: An Alternative Answer to the Italian Question. Matador.

Putnam, R. 1993. Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy . Princeton University Press.

-Putnam, Robert D., Lewis M. Feldstein, and Don Cohen. 2003. Better together: restoring the American community. NYC: Simon & Schuster.

-Saco, D. 2002. Cybering democracy: public space and the Internet Electronic mediations: v. 7

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

18

-Shirky, C. 2011. The political power of social media: technology, the public sphere and political change.

Foreign Affairs, Jan/Feb 2011.

- Schuler, D. and Day P. 2004. Shaping the network society: the new role of civil society in cyberspace.

Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Sunstein, Cass R. 2007. Republic.com 2.0. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wellman, B. and Rainie, L. 2012. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge : MIT

Press.

-Wittkower, D. The Vital Non-Action of Occupation, Offline and Online.

International Review of

Information Ethics Vol. 18 (12/2012).

Woodcock, G. 2004. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements . Univ. of Toronto Press

ARTICLES ON TUNISIA, CHINA AND ITALY:

-Breuer, A. 2012. The role of social media in mobilizing political protest evidence from the Tunisian revolution . Bonn, Germany: Deutsches Institute fur Entwicklungspolitik.

-Khamis Sahar and Katherine Vaughn. 2013. Cyberactivism in the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions:

Potentials, limitations, overlaps and divergences . Journal of African Media Studies no. 5 (1):69-86.

-Halverson J.R., Ruston S.W., Trethewey A. 2013. Mediated Martyrs of the Arab Spring: New Media, Civil

Religion, and Narrative in Tunisia and Egypt.

Journal of Communication 63 (2013) 312–332.

-Hartleb, Florian. 2013. Anti-elitist cyber parties? Journal of Public Affairs (14723891). Nov2013, Vol. 13

Issue 4, p355-369. 15p.

Roach S., 2012. China’s connectivity Revolution. Project Syndicate. 26 of January 2012.

-Tiso, Giovanni. 2013. The net will save us . Overland. Winter2013, Issue 211, p55-60. 6p.

-Natale, Simone, Ballatore, Andrea. 2013. The web will kill them all: new media, digital utopia, and political struggle in the Italian 5-Star Movement.

Media, Culture & Society. Jan2014, Vol. 36 Issue 1, p105-121. 17p.

- Ip Iam-Chong (ed. by) with contributions of Zheng, Portnoy; Chang, Teck-Peng; Lam, Oi-Wan; Liu, Shih-

Diing; Hu, Yong. 2011. Social Media Uprising in the Chinese speaking world . Amazon Media EU SARL.

-Li, Xiaobing. 2010. Civil liberties in China [electronic resource] / Xiaobing Li , Understanding China today : Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

-

Lu, Yiyi. 2010. “

Chinese Protest in the Age of the Internet.

” China Real Time Report. The Wall Street

Journal, 14 Dec. 2010.

-MacKinnon R. 2012. China’s networked authoritarianism . In Diamond L., Plattner M. 2012. Liberation technology. Social media and the struggle for democracy . Johns Hopkins University Press.

19