Almost no one in the film world believed that a film could be created

advertisement

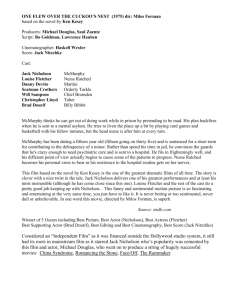

Almost no one in the film world believed that a film could be created successfully from Ken Kesey’s hallucinatory, nonlinear novel, yet, through Milos Forman’s direction, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest not only succeeded but garnered significant critical and popular acclaim. Forman brought his unique vision of realism and revelation to the work: he chose actors capable of flexible and spontaneous approaches, including some unknown or nonprofessional actors. Jack Nicholson, already a star, excelled under Forman’s direction. At the beginning of the film, when the prison guards remove McMurphy’s manacles, he laughs gleefully, grabs the guard and kisses him. As they rehearsed, Forman did not feel he was getting the response he wanted from the actor playing the guard. Taking Nicholson aside, Forman told him on the next take to kiss the other guard, who was not expecting it. That spontaneous take made it into the film. Most of the supporting cast members were little-known actors. Some, like Danny DeVito (Martini) and Christopher Lloyd (Taber), went on to long Hollywood careers after their success in this film. Forman coaxed particularly fine work out of the newcomer Brad Dourif as Billy Bibbit, the suicidal stutterer: Dourif won the 1975 Golden Globe award for Best Film Debut. Two key characters were played by nonactors, yet under Forman’s direction they gave subtle and believable performances as Dr. Spivey and the Chief. Forman enhanced the reallife feel of the movie by utilizing nonactors. Forman’s use of actual settings and natural light, as well as his emphasis on the human face, also emphasizes the film’s realism. He wanted the audience to realize that the mental institution and its inmates are not far removed from the rest of the world. Forman shot locked doors, wire screens, bars, and chain-link fences to underscore the repression of the people caught inside. The hard, white surfaces of the walls, floors, and tiles intensify the contrast between the institution and its human inhabitants. Forman uses close-ups of the characters’ faces to tell their stories. In order to increase the tension of the scenes, he uses extremely close shots, cropping out characters’ hair or necks. By concentrating on eyes and mouths, particularly expressive features, Forman stresses the men’s humanity. Most of the film occurs in short takes, edited to provide multiple points of view in each scene. During the group therapy sessions, the camera moves from face to face without lingering. Nurse Ratched is smug and controlled as she asks painful, personal questions. Cheswick holds his breath and looks like he will implode. Martini grins and scowls simultaneously. Billy Bibbit folds himself into a near-fetal position. These short takes of varied perspective consistently build tension in the scenes. Another of Forman’s strengths as a director is his ability to use varied camera work to capture the moments at which characters reach important revelations. For example, he sets the moment of McMurphy’s epiphany apart through the use of an unusually long take. He cuts quickly back and forth between the doctors and McMurphy at his sanity evaluation, so when he shoots one long, unedited take of McMurphy’s face, the importance of the scene stands out. When McMurphy sends Billy Bibbit to sleep with Candy, then sits by the open window, Forman again keeps the camera on McMurphy’s face, this time for a full sixty-five seconds. McMurphy in turn becomes troubled, thoughtful, and somber. He shows a hint of a grin as he realizes the cost of his sacrifice, looks up toward the open window, and then closes his eyes in acceptance. Under Forman’s tutelage, actors fully inhabit their roles, the hospital becomes an evil institution, and the movie poignantly celebrates the human spirit.