THE DUNDRUM QUARTET V1.0.22 300610

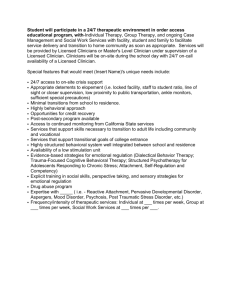

advertisement