FROM ISOLATION TO EMPIRE

advertisement

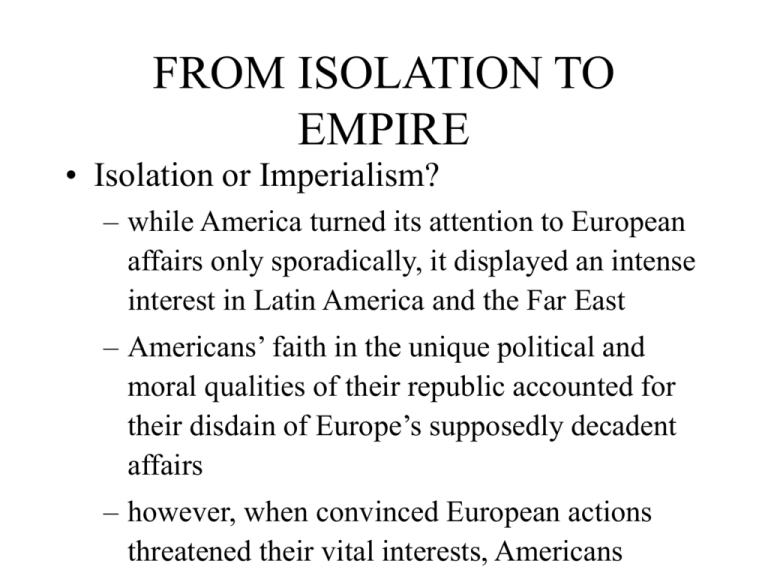

FROM ISOLATION TO EMPIRE • Isolation or Imperialism? – while America turned its attention to European affairs only sporadically, it displayed an intense interest in Latin America and the Far East – Americans’ faith in the unique political and moral qualities of their republic accounted for their disdain of Europe’s supposedly decadent affairs – however, when convinced European actions threatened their vital interests, Americans – America forcefully pressed its claims against England arising from the Civil War and aggressively sought an end to a ban on American pork products by France and Germany • Origins of the Large Policy: Coveting Colonies – in the post-Civil War years, America began to take hesitant steps toward global policies – the purchase of Alaska and the Midway Islands provided toeholds in the Pacific basin – attempts to purchase or annex the Hawaiian Islands, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic signaled growing interest in the outside world – by the late 1880s, the United States had begun an active search for external markets for its agricultural and industrial goods – with the so-called closing of the frontier, many Americans looked to overseas expansion – intellectual trends added impetus to the new global outlook – Anglo-Saxonism, missionary zeal, and European imperialism opened American eyes to the possibilities inherent in expansion – finally, military and strategic arguments justified a large policy • Toward an Empire in the Pacific – American interest in the Pacific and the Far East was as old as the Republic itself – the opening of Japan to western trade increased America’s interest in the Far East – despite Chinese protests over the exclusion of their nationals from the United States, trade with China remained brisk – strategic and commercial concerns made the acquisition of the Hawaiian Islands an increasingly attractive possibility – growing trade and commercial ties, a substantial American expatriate community, and, after 1887, the presence of an American naval station all pointed toward the annexation of Hawaii – in 1893, Americans in Hawaii deposed Queen Liliuokalani and sought annexation by the United States – despite opposition from anti-imperialists and some special interests, the U.S. annexed Hawaii in 1898 • Toward an Empire in Latin America – in addition to traditional commercial interests in Latin America, the United States became increasingly concerned over European influence in the region – in spite of the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty (1850), the United States favored an American-owned canal; in 1880, the United States unilaterally abrogated the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty – in 1895, a dispute between Venezuela and Great Britain over the boundary between Venezuela and British Guiana nearly brought the United States and Britain to blows – the United States and Great Britain rattled sabers, but war would have served neither side – finally, pressed by continental and imperial concerns, Britain agreed to arbitration – after this incident, relations between Britain and America warmed considerably • The Cuban Revolution – Cuban nationalists revolted against Spanish rule in 1895 – Spain’s brutal response aroused American public opinion in support of the Cubans – President Cleveland offered his services as a mediator, but Spain refused – American expansionists, citizens sympathetic to Cuban independence, and press (led by Hearst’s Journal and Pulitzer’s World) kept issue alive – publication of de Lôme’s letter and explosion of battleship Maine in February 1898 pushed the United States and Spain to the brink of war • The “Splendid Little” Spanish-American War – on April 20, 1898, a joint resolution of Congress recognized Cuban independence and authorized the president to use force to expel Spain from the island – the Teller Amendment disclaimed any intent to annex Cuban territory – the purpose of the war was to free Cuba, but the first battles were fought in the Far East, where, on April 30, Commodore Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay – by August, Americans occupied the Philippines – American forces won a swift victory in Cuba as well – Spain agreed to evacuate Cuba and to cede Puerto Rico and Guam to the United States – the fate of the Philippines was determined at the peace conference held in Paris that October • Developing a Colonial Policy – almost overnight, the United States had obtained a substantial overseas empire – some Americans expressed doubts over the acquisition of the Philippines, but expansionists wanted to annex the entire archipelago – advocates of annexation portrayed the Philippines as markets in their own right and as the gateway to the markets of the Far East – many Americans, including the president, were swayed by “the general principle of holding on to what we can get” • The Anti-Imperialists – the Spanish-American war produced a wave of unifying patriotism that furthered sectional reconciliation – however, victory raised new and divisive questions – a diverse group of politicians, business and labor leaders, intellectuals, and reformers spoke out against annexing the Philippines – some based their opposition on legal and ethical concerns; for others, racial and ethnic prejudice formed the basis of their objections – in the end, swayed by a sense of duty and by practical concerns, McKinley authorized the purchase of the Philippines for $20 million – after a hard-fought battle in the Senate, the expansionists won ratification of the treaty in February 1899 • The Philippine Insurrection – early in 1899, Philippine nationalists, led by Emilio Aguinaldo, took up arms against the American occupation – atrocities, committed by both sides, became commonplace – although American casualties and the reports of atrocities committed by American soldiers provided ammunition for the anti-imperialists, McKinley’s reelection settled the Philippine question for most Americans – William Howard Taft became the first civilian governor and encouraged participation by the Filipinos in the territorial government – this policy won many converts but did not end the rebellion • Cuba and the United States – at the onset, the president controlled the fate of America’s colonial possessions, but eventually the Congress and the Supreme Court began to participate in this process – the Foraker Act (1900) established a civil government for Puerto Rico – a series of Supreme Court decisions determined that Congress was not bound by the limits of the Constitution in administering a colony – freedom did not end poverty, illiteracy, or the problem of a collapsing economy in Cuba – the United States paternalistically doubted that the Cuban people could govern themselves and therefore established a military government in 1898 – eventually, the United States withdrew, after doing much to modernize sugar production, improve sanitary conditions, establish schools, and restore orderly administration – a Cuban constitutional convention met in 1900 and proceeded without substantial American interference – under the terms of the Platt Amendment, the Cubans agreed to American intervention when necessary for the “preservation of Cuban independence,” promised to avoid foreign commitments endangering their sovereignty, and agreed to grant American naval bases on their soil – although American troops occupied Cuba only once more, in 1906, and then at the request of Cuban authorities, the threat of intervention and American economic power gave the United States great influence over Cuba • The United States in the Caribbean – the same motives that compelled United States to intervene in Cuba applied throughout region – Caribbean nations were economically underdeveloped, socially backward, politically unstable, desperately poor, and threatened by European creditor nations – United States intervened repeatedly in region under broad interpretation of Monroe Doctrine – in 1902, the United States pressed Great Britain and Germany to arbitrate a dispute arising from debts owed them by Venezuela – the Roosevelt administration took control of the Dominican Republic’s customs service and used the proceeds to repay that country’s European creditors – the Roosevelt Corollary to Monroe Doctrine announced that United States would not permit foreign nations to intervene in Latin America – since no other nation could step in, the United States would “exercise . . . an international police power” – short run, this policy worked admirably; in long run, it provoked resentment in Latin America • The Open Door Policy – when the European powers sought to check Japan’s growing economic and military might by carving out spheres of influence in China, the United States felt compelled to act – Secretary of State Hay issued a series of “Open Door” notes, which called upon all powers to honor existing trade agreements with China and to impose no restrictions on trade within their spheres of influence – although an essentially “toothless” gesture, this action signaled a marked departure from America’s isolationist tradition of nonintervention outside of the Western Hemisphere – within a few months, the Boxer Rebellion tested the Open Door policy – fearing that European powers would use the rebellion as an excuse for further expropriations, Hay broadened the Open Door policy to include support for the territorial integrity of China – the Open Door notes, America’s active diplomatic role in the Russo-Japanese War, and the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907 all engendered ill feelings between the United States and Japan • The Panama Canal – American policy in the Caribbean centered on the construction of an interoceanic canal, thought to be a necessity for trade and an imperative for national security – Hay-Pauncefote Agreement (1901) abrogated Clayton-Bulwer Treaty and ceded to the United States construction rights to such a waterway – the United States negotiated a treaty for the right to build a canal across Panama with the government of Colombia, which the Colombian senate rejected – when the Panamanians rebelled against Colombia in 1903, the United States quickly moved to recognize and insure Panama’s independence – the United States then negotiated a treaty with the new Panamanian government, which yielded to the United States a ten-mile-wide canal zone, in perpetuity, for the same monetary terms as those earlier rejected by Colombia • “Non-Colonial Imperial Expansion” – America’s experiment with territorial imperialism lasted less than a decade – however, through the use of the Open Door policy, the Roosevelt Corollary, and dollar diplomacy, the United States used its industrial, economic, and military might to expand its trade and influence – at times, America also engaged in cultural imperialism, attempting to export American values and American system to weaker nations – despite America’s emergence as a world power, the national psychology remained fundamentally isolationist