Lecture 9 - Plattsburgh State Faculty and Research Web Sites

advertisement

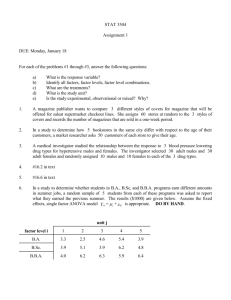

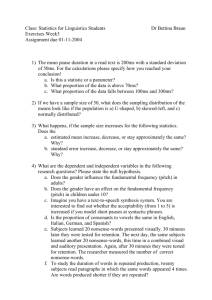

Chapter 11 The evolution of mating systems Monogamy: one male one female Polygamy Polygyny: one male, multiple females. Polyandry: one female, multiple males. Polygynandry: multiple males, multiple females. Monogamy Prolonged, essentially exclusive bond maintained with one member of opposite sex. Generally a rare system. Rare in mammals (except for some rodents, primates and dogs). However, is commonest avian mating system. Monogamy armed compromise rather than happy collaboration. Males would generally like to seek extra mates. Why don’t they? Several hypotheses: Mate-guarding hypothesis Mate assistance hypothesis Female enforced monogamy Mate guarding hypothesis (MGH) Monogamy may be best choice if female would mate again if male deserted her and if 2nd male would fertilize eggs. Mate guarding should pay off when females: 1. Scarce and hard to find. 2. Remain receptive after mating. Example: Clown shrimp. Mate assistance hypothesis (MAH) Male stays with partner because male assistance increases young’s survival. Increased survival of young outweighs extra young gained by seeking extra mate In seahorses, males carry brood in pouch during 3 week “pregnancy.” Pair stays together for series of matings. Male can hold only one clutch, so no benefit in courting extra females. Females choose monogamy because males are scarce and because females are poor swimmers and thus vulnerable to predators. Female enforced monogamy hypothesis (FEMH) In some species females actively prevent males obtaining extra mates. A female burying beetles will attack her mate if he tries to release pheromones to attract other females to a carcass the pair have buried. In experiment, males whose female had been tethered so she could not attack him released pheromones for longer period than males whose mate wasn’t tethered. Monogamy in birds Male birds can feed young as well as females (unlike most mammals). Male assistance essential to rearing young. Probably explains why > 90% of birds are monogamous. Male assistance in Snow Buntings essential to rearing young. Females whose males were removed reared fewer than 3 young. Those with males reared 4 or more. In many birds raising young so hard, it takes a pair to rear even one young (e.g. albatrosses). In Tree Swallows polygynous males father fewer surviving young (0.8 fledglings) than monogamous males (3.0 fledglings). More offspring of polygynous males die because male can’t help both females (MAH). Females also mate with other males because male cannot guard two females effectively (MGH). Monogamy best for both male and female Tree Swallows. Extra-pair copulations (EPC’s) in birds. Even though monogamous males assist one primary female, males also seek EPC’s. DNA fingerprinting has shown EPC’s very common. DNA fingerprints Right: Beta (**) male unique band occurs in offspring D, E, and F. * * ** * Above: * indicates unique alpha bands Alpha fathered all young. Alpha male (*) and offspring G share unique band. Male benefits of EPC’s are obvious (increased offspring at low cost). Why would females seek EPC’s? Female may gain by : 1. Increasing chances of her eggs being fertilized. Female red-winged blackbirds who mate with multiple males have higher egg hatching rates. Similarly, female adders who mate with multiple males have fewer stillborn young. 2. Obtaining better genes for her offspring Many female Blue Tits mate with neighboring males whose mates don’t seek out other males. These males survive better and produce more young than males with unfaithful mates. Suggests they have better genes. 3. Obtaining resources from male Female red-winged blackbirds that copulate with neighboring males are allowed to forage on the males territory. Males RWB’s also assist in attacking predators in vicinity of those females nests. Polygamy Any mating system involving mating with and, in many cases, forming pair bonds with multiple members of the opposite sex. Three kinds: Polygyny Polyandry Polygynandry Polygyny: One male mates with two or more females. Examples : Birds: Lark Bunting, Red-winged Blackbird, Dunnock, Marsh Wren. Marsh Wren Mammals: Lions, Gorillas, Bats. Also found in many fish, insects, etc. Three basic types of Polygyny 1. Resource defense Polygyny 2. Female defense Polygyny 3. Lek Polygyny 1. Resource defense polygyny. Male defends resources that females need to produce young (food, nesting sites). Resource defense polygyny in an African cichlid African cichlid fish Lamprologus callipterus exhibits extreme sexual dimorphism (males 13X times larger than females). Females lay eggs inside empty snail shells and remain inside shell until eggs hatch. Males collect suitable shells and steal them from other males. Males gather shells into large collections and defend them from rival males. Up to 86 shells have been recorded in one collection and up to 14 females at once. Males with good territories obtain high reproductive success. Extremely large male body size has been selected for because it enables males to collect shells and to defend their territories. Male Red-winged Blackbirds hold territory on marshes. Males with the best territories attract harems of up to 15 females. Females choose males on the basis of territory quality. Male’s red epaulettes are essential in male-male competition. Polygyny threshold model Some females choose to mate with already mated males who will not help them feed their chicks even though unmated males with territories are available. Why would a female do this? Polygyny threshold model: predicts that female will accept role of 2nd mate (polygyny) when superior resources on males territory mean that female would do better there than as 1st mate on a poor territory Curves represent payoffs to female. Female can choose between males A and B. A has a mate, B is unmated. Polygyny threshold model Example of polygyny threshold. Male Lark Buntings establish territories in grassy, open habitats. Mate with > 1 female but assist only first female to settle on their territory. Some female LB’s accept secondary female role on good territory to obtain a high quality nesting site. In bad nest sites young die from exposure to the sun. Some male Pied Flycatchers establish two territories. Sing to attract a female. Males provide little help to female on 2nd territory, so female has low reproductive success. Each female mated to a polygynous male has lower reproductive success than a monogamous female. However, males r.s. is higher than that of a monogamous male Male Pied Flycatchers clearly try deceive females into polygyny. Not clear yet if females really fooled or have no better alternative. 2. Female defense Polygyny. Common when females cluster in groups that are defensible. Males then defend clusters against other males. E.g. Elephant seals, lion prides, elk and deer herds. In some marine siphonoecetine amphipods, which build protective cases out of gravel and shells, males collect females and glue their houses to their own. In general, female defense polygyny possible because females cluster for their own reasons and males exploit this. E.g. Lionesses cluster to defend feeding territories. Deer gather for protection. Elephant seals gather on the few suitable nursery beaches. 3. Lek Polygyny Males do not help in raising the young. Variance in male mating success is greatest in this system. Examples: Grouse, Ruffs, manakins. Cock-of-the-rock. In lekking species males display for females at a predictable location (a lek) and females come to the site to choose mates. Males provide no resources except sperm. Males display for females. Females choose males on basis of appearance and displays (sexual selection). Sage Grouse displaying on a lek. Highly skewed mating success is normal in lekking systems. A few males obtain most of the matings. By mating with best possible male, females obtain the best available genes for their offspring. In well-studied Black Grouse and Sage Grouse lekking systems < 10% of males obtain 70-80% of the copulations. Why do males gather in leks? Gathering in leks may reduce predation risk. Open country birds display in groups whereas forest species usually display solitarily. Birds-of-paradise that display in leks are edge or second-growth species (where predation risk is high) whereas primary forest species display solitarily. Three most favored hypotheses for evolution of lekking are: 1.“Hot-spots” hypothesis 2. “Hot-shots” hypothesis 3. Female preference hypothesis. Hot-spots Hypothesis: males gather at sites where they are likely to encounter females. Lekking bees, wasps and other insects often use same locations for leks. Territories of lekking flycatchers, manakins and hummingbirds also often overlap. Gather along streams or ridgelines that act as highways for female movement. Convergence of different species on same location supports hot-spot hypothesis. Hot-shots Hypothesis: subordinate males cluster around most attractive males -“hot-shots” -- in order to be seen by or to intercept females attracted to these males. In Great Snipe (a bird) removing central dominant bird caused neighbors to leave territories. Removal of subordinates resulted in their territories being refilled. In Black Grouse on long-lasting leks location of most popular territory shifts from year to year. Suggests male quality more important than location in lek. Female Preference Hypothesis: females prefer to choose from groups of males because comparisons are easier to make. The mating behavior of the Ruff appears consistent with all three hypotheses. Male ruffs are named for their well-developed ruffs, which they use to display to females (reeves). Ruffs are polymorphic with ruffs occurring in a variety of colors. Male ruffs use a variety of mating strategies. They pursue females (followers), wait for them at rich feeding ground (interceptors) or wait at classic leks (lekkers). White-ruffed males appear to have evolved as specialist Followers skilled at tracking the movements of females between neighboring leks. Male ruffs may switch tactics but committed lekkers have the highest mating success. Dark morph ruff displaying to a female. Controlled experiments suggest that female ruffs prefer larger leks. This preference increases the mating success of males at large leks and favors that breeding strategy. Female ruffs prefer groups of at least five males and visit such groups more often. Leks with >5 males do not attract more females, thus satellite males reduce success of dominant males by intercepting some of the females. Hot-spots and hot-shots hypotheses also relevant to ruff mating system. Leks tend to be located by ponds where females come to feed (Hot-spots). Satellite males gather around most successful males (Hot-shots). The clustering of males on leks may in part be due to a tendency of young or inexperienced males to gather near older or successful males. Such satellite males may get occasional matings and perhaps gradually improve their status. Such associations are most extremely developed in the Central and South American manakins. Cooperative leks displays. In many manakins males perform cooperative displays. Three or four males may cooperate to display but usually only the alpha male gets to mate. Round-tailed Manakin Cooperative display of Swallow-tailed Manakins. In Long-tailed Mankin males may take 8 years to move up to alpha position. Four year study: in 117 observed copulations only 8 of 85 males copulated. 90% of copulations by 4 males and 67% by one alpha male. Long-tailed Manakin Manakin mating system works because birds are long-lived and females tend to return to where they mated before. As a result, the beta and lower-ranking males can expect to inherit a high-quality display ground and can afford to delay mating. Polyandry: One female forms pair bonds with two or more males. Female reproductive success is more variable than male reproductive success in polyandrous mating systems. There are two forms: classic polyandry and cooperative polyandry. Classic Polyandry: Females lay clutches for multiple males and compete for males. Examples : Jacanas, Phalaropes, Spotted Sandpiper. Cooperative Polyandry: Two or more males cooperate to assist a female at one nest. Examples: Acorn Woodpeckers, Dunnock. In classic polyandry females brightly colored and compete for territories and males. Males incubate eggs and care for young. Female Red Phalarope. Male Jacanas (lilytrotters) defend small territories against other males. Females defend larger territories that include several male territories. Female jacana lays clutch of eggs for each male in her territory. Male alone incubates eggs and cares for the young. Losses of eggs and chicks to predators and nest flooding may be high. Clutch of jacana eggs. Male Pheasant-tailed Jacana incubating. If female jacana loses her territory or dies and another female takes over the territory, the new female destroys the eggs and kills young of any male on territory. This behavior frees the male to incubate a replacement clutch, which new female provides. Female Spotted Sandpipers are 25% larger than males. Female will lay clutches for a primary male and from 1-3 secondary males. Only the last secondary male is assisted by the female in caring for the young. However, later males are likely to have lower reproductive success because sperm from earlier males may fertilize some of eggs. Not clear how classic polyandry has evolved. May be a result of heavy losses of eggs which favor females maximizing egg output (Jacanas). Alternatively, in Spotted Sandpipers cause may be phylogenetic constraints that limit females to four egg clutches. Females can produce more eggs because food sources are rich, but must lay more clutches not bigger ones. Hence, need males to incubate. Rare case of females being limited by access to mates rather than by gamete production. Cooperative Polyandry also occurs in which more than one male assists a female. Appears to be result of shortage of breeding opportunities because there are few territories available. Groups of Acorn Woodpeckers compete for territories that contain granary trees. Cooperative Polyandry may arise when a multiple male coalition controls a territory with only one breeding female. In Dunnocks cooperative polyandry occurs when two males partition a females territory. Polygynandry: Two or more females form pair bonds with two or more males. Examples : Ratites (i.e. Rheas and Ostriches), Dunnocks, Acorn Woodpeckers. Arises in similar circumstances to those just described for Cooperative Polyandry. The mating system of the Dunnock “Unobtrusive, quiet and retiring, without being shy, humble and homely in its deportment and habits, sober and unpretending in its dress, while still neat and graceful, the dunnock exhibits a pattern which many of a higher grade might imitate, with advantage to themselves and benefit to others through an improved example.” The Reverend F.O. Morris (1856) encouraging his parishioners to emulate the humble life of the Dunnock. Little did he know! The Dunnock is an unobtrusive brown and gray bird that is common in woodlands, hedgerows, and urban areas in Europe. The Dunnocks breeding in the Cambridge University Botanical Gardens have been the subject of long-term research by Nick Davies and colleagues. These studies have revealed a mating system that the Reverend Morris might have hesitated to recommend to his parishioners. Dunnocks feed on small arthropods and establish and defend exclusive territories, which they retain year-round. Subject of long-term studies by Nick Davies and colleagues in Cambridge University Botanic Gardens Females establish and defend their territories against other females. Females choose their nesting territories independently of males and compete for space with other females. Territory size is a function of food availability. The more food is available the smaller territories are. Dunnock 1990 female territories Male Dunnocks also defend territories but as is the case for females, only against members of their own sex. Males impose themselves on the female distribution and attempt to monopolize access to the females territories. Dunnock 1990 male territories Female territories 1990 Male territories 1990 Monogamy arises when a male can control all of a females territory. In spring, males pursue females around their territories thus learning the territory’s boundaries and singing to stake their claim. A male who can control a single territory is monogamous. A male who can control more than one territory is polygynous. Polyandry usually arises when a female’s territory lies between the territories of two males. Each male attempts to pursue the female into the other males territory. At first each male is dominant in its own territory, but eventually one male (the alpha) establishes dominance and the two males (alpha and beta) defend the females territory together. Polyandry may also arise when a young male persistently intrudes onto an older males territory until he eventually is accepted as a beta male. Polygynandry may occur when in adjacent monogamous pairs one male invades the adjacent territory and eventually becomes the alpha male in a two female territory. Female territory size is crucial in determining the mating system. The larger the female territories are the harder it is for any mating system other than monogamy or polyandry to arise because males cannot defend very large territories. Territory size is a function of food availability. The more food available the smaller female territories are. If food is added, female territory size is reduced and this facilitates polygyny and polygynandry Males are larger than females and dominant over them in aggressive interactions. When food is scarce, females lose out to males. female As a result of male dominance, female mortality is higher in severe winters. As a consequence of differential mortality the population sex-ratio is male-biased after severe winters. A shortage of females leads to an increase in polyandry. Males and females both try to maximize their reproductive output. Male and female payoffs differ in different mating systems. Payoffs For male For female Polyandry Share one female Sole access to multiple males Monogamy Sole access to one female Sole access to one male Polygynandry Share several females Share several males Polygyny Sole access to Share one male several females When more than one male feeds a brood more young are fledged and they are bigger. The larger young are at fledging the better their chance of surviving to independence. A male’s payoff is highest when he can mate with multiple females. A female’s reproductive success is highest when she can obtain the assistance of more than one male to care for her brood. These aims are in opposition in polyandrous and polygynandrous mating systems. In a polyandrous or polygynandrous mating system a female dunnock tries to encourage both males to feed the young. She does this by mating with both males and giving them paternity in the brood. The alpha male, however, wishes to control mating access to the female because although more young are reared when both males feed the brood, the number of young he fathers is reduced. Male Dunnocks try to maximize their reproductive success by engaging in sperm competition and mate guarding. Sperm Competition In Dunnocks sperm competition is intense. Male Dunnocks produce > 1000 times the amount of sperm that the comparably sized Zebra Finch does. Females store sperm in special sperm storage glands. Sperm Competition Both males mate with the female as often as they can to maximize the amount of their sperm in the female’s sperm storage glands. Both males also engage in cloacal pecking. In this behavior the male before mating pecks the females cloaca and she ejects stored sperm from her sperm storage glands. Mate Guarding The alpha male guards the female and tries to prevent her from mating with the beta male. If the beta male attempts to mate, the alpha male intervenes and drives him away from the female. The female encourages the beta male to mate and attempts to escape from the alpha male and mate with the beta male. Mate Guarding The alpha male intervenes in copulation attempts made by the beta male. Both males frequently inspect the nest to see if eggs have been laid and value copulations during the egg-laying period particularly highly as these are most likely to produce offspring. After the eggs have been hatched beta males base their decision on whether to feed the brood or not on the amount of mating access they have had to the female. The greater the mating access a beta male has had the more often he feeds the young. DNA fingerprinting results have been very useful in teasing apart the mating success of males and females in these complex mating systems. Right: Beta (**) male unique band occurs in offspring D, E, and F. * * ** * Above: * indicates unique alpha bands Alpha fathered all young. Alpha male (*) and offspring G share unique band. The Dunnock’s mating system results from the interaction of multiple factors both ecological and behavioral. Food supplies and winter conditions affect female territory size which determines how many female territories a male can defend. This in turn leads to complex behavioral maneuvering as both sexes attempt to maximize their reproductive success. Hardly, the picture of domestic tranquility that the Reverend Morris had in mind!