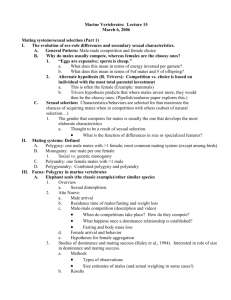

Parental Investment & Mating Systems

Mating Systems

&

Parental Care

Mating Systems & Parental Care

Chapter 18

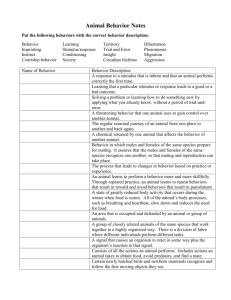

Mating Systems

Parental Care

Who Invests in Offspring?

Parent-Offspring Recognition

Not covered in lecture

Parent-Offspring Conflict

Sibling rivalry

Chapter 18 2

Factors Affecting Type of Mating

System

Sexual Selection

Differential allocation of resources into gamete production and parental care

Sperm is cheap, eggs expensive

Chapter 18 3

Factors Affecting Type of Mating

System

Female Male

Limits to

Reproductive

Success

# of eggs produced

# of matings

1. Males should be competitive among themselves for opportunities to mate (Intrasexual competition)

2. Females should be choosy: any mating may involve a big investment on her part, so she should be selective about it (Intersexual competition)

Chapter 18 4

Sexual selection underlies the evolution of male competition and female choice.

Type of Mating System dependent on:

Amount of parental care required

Ecological factors

Chapter 18 5

Mating Systems

Most classifications of mating systems based on extent of bonding/association between male and female during mating.

Problem:

judgment is needed to determined what constitutes an association

Subjective

Emlen & Oring (1977)

Chapter 18 6

Mating Systems

Emlen & Oring (1977):

Classification based on ability of one sex to monopolize or accumulate mates

Eliminates need for subjective judgment

Emphasizes the ecological and behavioural potential for monopolization

Chapter 18 7

Resource-based Mating Systems

Emlen and Oring (1977)

• the ecology of an organism may not permit males to have more than one partner.

•Females widely distributed and males cannot monopolize them.

•Females may mate with another male so monogamy may serve to guard the female.

•If males help rear young, fitness increases through increased young survival.

•The evolution mating systems is driven by the distribution of resources in the environment for both the male and the female.

Chapter 18 8

Mating Systems

Monogamy - 1 male, 1 female mate guarding mate assistance female enforced

Polygyny - 1 male, many females resource defense female defense scramble competition explosive breeding assemblage lek

Polyandry - 1 female, many males male defense resource defense

Promiscuity

Chapter 18 9

Mating Systems

Males can produce lots of sperm almost continuously

Monogamy is not best for a male

Females often need help in raising offspring, so monogamy is good for her

Sexual selection theory and coupled with low parental investment of males suggest that polygynous mating systems should be most common.

Why are males?

Chapter 18 10

Mating Systems

Monogamy

(Association of) 1 male & 1 female

Neither sex is able to monopolize more than one member of the opposite sex

Mate for season only, or for life

Genetic constraints vs. social/ environmental factors (e.g., seabirds socially monogamous)

Chapter 18 11

Mating Systems

Polygamy

Matings with multiple partners; nonmonogamous systems

Polygyny : “many” females

Males able to monopolize >1 female

Polyandry : “many” males

Females able to monopolize >1 male

Chapter 18 12

Mating Systems

Promiscuity

Multiple matings by at least one sexes

Absence of prolonged associations

Chapter 18 13

Spatial distribution of resources influences type of mating system

Fig. 18.1

Dots = resources, circles = defended areas

Chapter 18 14

Polygamy - Types of Polygyny:

Resource-defence polygyny:

Males defend areas containing food or nesting sites that females need for reproduction

Territories differ quality (clumped distribution)

May reach a point where a female can do better by mating with an already-mated male on a good territory than an unmated male on a poor territory = polygyny threshold

Chapter 18 15

Polygyny

Threshold

Fig. 18-3

(a) (b)

The quality of territory at (b) is greater than at (a) . A female joining an already-mated male at (b) will have the same RS (c) as a female in a monogamous pair at (a) .

Chapter 18 16

Polygamy – Types of Polygyny

Resource-defence polygyny (cont’d):

Facultative (optional) polygyny :

Dependent on locale (clumped, defensible resources: polygyny ; vs. spread-out, nondefensible: monogamy )

Thus, same species may behave differently in different environments

Chapter 18 17

Polygamy – Types of Polygyny

Female-defence polygyny:

Females aggregate for reasons unrelated to mating

E.g., female elephant seals haul out onto land to give birth, sites limited

– Males compete to monopolize the grouped females, defend harem from other males

Chapter 18 18

Polygamy – Types of Polygyny

Male dominance polygyny

Neither resources nor females can be monopolized

Males gather and display, females choose based on quality of display

Usually on leks (mating areas where males congregate and defend small territories while displaying for females)

E.g., bowerbirds; sage grouse

Chapter 18 19

Polygamy – Types of Polygyny

Male dominance polygyny (cont’d)

Mating success skewed in favour of a small number of males

Dominant males may have:

Preferred territory locations within lek

Most attractive display (e.g., bower)

Most elaborate ornaments, etc.

“Copying” behaviour seen in females

Chapter 18 20

Polygamy – Types of Polygyny

Scramble Polygyny

Males actively search for mates without overt competition

Large groups of females congregate, males concentrate only on inseminating females or fertilizing eggs, ignore other males (e.g., wood frogs, horseshoe crabs); OR

Widely disbursed females are actively pursued by males (e.g., thirteen-lined ground squirrels)

Chapter 18 21

Polygamy – Types of Polyandry

Resource-defence polyandry

Females control access to males indirectly by monopolizing critical resources e.g., spotted sandpiper – females compete for control of breeding territories

Chapter 18 22

Polygamy – Types of Polyandry

Female-access polyandry

Females do not defend resources essential to males, but they interact among themselves to limit access to males

e.g., American jacanas – some females defend “superterritories” which encompass the territories of several males, prevent access to other females

Chapter 18 23

Polyandry

Rare –

Females more brightly coloured, etc. (sexuallyselected traits)

Females show philopatry

(returning to natal territory after maturity)

:

True of males in polygynous species

Chapter 18 24

Ecology & Mating Systems

Mating systems related to resource distribution

Two sympatric (i.e., coexist in same area) species of Agelaius (Orians, 1961)

Red-winged blackbirds

Chapter 18

Tricoloured blackbirds

25

Ecology & Mating Systems

Red-winged Black Birds:

Usually polygynous

Male defend territory with 2 or 3 females

Male arrives 3-4 wk before females (often natal territory), defends territory until young are fledged (several months)

Rarely help raise young – females build nests and incubate

Chapter 18 26

Ecology & Mating Systems

Tricoloured Black Birds:

Monogamous

Nomadic colonies of 100-200,000 birds

Establish territories, find mates, build nests, lay eggs

(biparental care) – ALL WITHIN 1 WEEK!

Both sexes make large investment, but in a smaller timeframe

Chapter 18 27

Ecology & Mating Systems

Why so different?

Depends on Energy source (food availability)

RWBB: Stable diet of seeds and insects, available for several months

TCBB: Mass feeding flights, attack ephemeral, concentrated food sources, e.g., ripe rice/grain fields

Chapter 18 28

Mouse MHC Probe

Gibbs, et al. 1990. Realized reproductive success of polygynous Red-winged Blackbirds revealed by

DNA markers. Science 250: 1394-1397.

Chapter 18 29

Alternative Mating Tactics

Members of same sex can use different tactics to obtain matings

E.g., some males fight, others sneak copulations by being inconspicuous or mimicking females

“Sneaky”, satellite, or parasitic males

E.g., bullfrogs: Dominant male calls to attract females to his territory; satellite male hides at edge, waits for females to approach

Chapter 18 30

Explosive Breeding Assemblage

•Females become receptive for only a brief time

•They go to a breeding area when they are ready

•Males gather at the breeding location and compete for the female.

Chapter 18 31

Alternative Tactics

Morphology

coho salmon: jacks vs. hooknoses

Hooknoses: built to fight

Jacks: smaller, mimic females, sneak fertilizations

(Fig. 18.8)

Chapter 18 32

Parental Care

Extent of parental care varies greatly across species

Ways to invest:

DNA (release sperm/eggs, move on)

Prenuptial feeding (e.g., crickets) – spermatophore nourishes female, more and better quality offspring

Direct care of offspring (incubating, feeding, brooding) – birds/mammals/some fish…

Chapter 18 33

See Text pg. 151 (Chapter 10)

Chapter 18 34

Which Sex Invests?

Taxonomic differences also exist in patterns of parental investment:

birds: monogamy / biparental care

mammals: polygyny / maternal care fish: promiscuity/polygyny / no parental care or male care

Why these differences?

Chapter 18 Photo by: Alan and Sandy Carey 35

Determinants of Parental

Investment in Vertebrates

Mode of fertilization

Internal fertilization – primarily female care

E.g., birds, mammals

External fertilization – primarily biparental or male care

E.g., fish

Chapter 18 36

Determinants of Parental

Investment in Vertebrates

Certainty of Paternity Hypothesis

Reliability of paternity assumed to be greater when eggs are fertilized externally (e.g., fish) rather than internally (e.g., mammals, birds)

Chapter 18 37

Determinants of Parental

Investment in Vertebrates

Association Hypothesis

Proximity of adults to offspring

Internal fertilization – females closer

External fertilization – both sexes close, but male/biparental care more common when offspring associated with a male’s territory

E.g., males defend territories, little extra energy to protect eggs already on territory

(e.g., fish)

Chapter 18 38

Determinants of Parental

Investment in Vertebrates

Phylogenetic Constraints:

Birds

Eggs develop externally

Incubation, feeding, guarding by both sexes

Mammals

Internal gestation

Lactation

Males can provide little care

Chapter 18 39

Determinants of Parental

Investment in Vertebrates

Phylogenetic constraints

Fish

External fertilization

Both sexes free to desert, or

Guard nest site

(territory)

Chapter 18 40

Determinants of

Parental Investment in Vertebrates

Reproductive Effort: Total energy expended in reproducing, which includes mating effort & parental care

May direct all reproductive effort into mating (e.g., codfish - lay eggs, fertilize them, swim away), OR

May expend much energy in parental care (e.g., primates – 25% of offspring’s lifespan)

Chapter 18 41

Reproductive Effort

Male

MALE

Female

FEMALE

Mating

System

ME

PE

PE PE

ME

PE

PE

PE

ME

PE

PE

ME

Polygamous/

Promiscuous

Chapter 18

Monogamous

42

Determinants of Parental

Investment in Vertebrates

How Do Ecological Factors Affect

Parental Investment?

K- & r-selection theory

“Bet-hedging” theory

Chapter 18 43

r - & K- Selection Theory

Stable environment

Larger body size

Slower development

Longer lifespan

Have young at intervals

( iteroparity );

K-selected (at/near carrying capacity of environment, K) few young that receive much care

Fluctuating environment

Small body size

Rapid development

Have young all at once

( semelparity ), r-selected (at/near reproductive rate of population, r) many young that receive little/no care

Chapter 18 44

“Bet-hedging” Theory

In environments where survival of offspring is low and unpredictable, parents may “hedge their bets” by putting in only a small reproductive effort each season

spread their reproductive effort out over time rather than all at once

e.g., California Gull: Lives 15+ yrs. As adults age, appear to increase effort (lay more eggs, feed chicks more food, defend more vigorously) due to their own decreasing reproductive potential.

Chapter 18 45

Parent-Offspring Recognition

Misdirected parental care can be costly (waste of energy, reduced fitness)

Fostering in seals

Recognition appears to evolve in species in which mixing of unrelated offspring is likely

Chapter 18 46

colonial ground-nesting gulls & terns:

precocial chicks mobile at ~5 days,

adults seem to develop recognition for own chicks at that time kittiwakes

cliff-nesters;

chicks fledge at 3 weeks

Parents do not seem to recognize offspring

Chapter 18 47

Parent-Offspring Conflict

Offspring demand more investment from the parent (usually mother) than the parent is willing to give

Trivers (1974): Natural selection acts differently on mother and offspring

Based on coefficient of relatedness and parental investment

Chapter 18 48

Parent-Offspring Conflict

Mother - should invest a certain amount of energy into first offspring, “wean” him, then invest in producing second offspring, when the cost of raising #1 starts to exceed the benefits of having #2…

Offspring - should “demand” investment from mother until such point that the mother’s fitness starts to decline (&, thus, so does his inclusive fitness, as he shares half his genes with her).

when cost of raising #1 becomes 2x the benefit to mother, offspring's inclusive fitness

Chapter 18 49

Parental Reproductive Success

How can parents increase their reproductive success and fitness?

Manipulation of dependent young

Chapter 18 50

Parental Manipulation

Parents may selectively provide care to certain offspring at the expense of others

Brood adjustment

Coots - selectively adjusts brood size by killing chicks (European) or feeding specific chicks (American)

Chapter 18 51

Parental Manipulation

Hatching asynchrony - milder form of brood adjustment: first-to-hatch have advantage, get more food, larger, can push others out of nest

(i.e., siblicide)

It is in parents’ interests to create inequalities in size of chicks: WHY?

biggest, strongest offspring survive and are more likely to reach reproductive age

Chapter 18 52

Sibling Rivalry

Pigs: “runt” gets least preferred teat (little milk); piglets have sharp teeth and fight for access to best nipples

young predatory birds (ex: boobies, eagles, egrets) kill younger siblings soon after hatching, may be because the second egg serves only as parental insurance in case the first fails to hatch.

Chapter 18 53

Case Study: Spotted hyenas

Chapter 18 54