The Harlem Renaissance - Mercer Island School District

advertisement

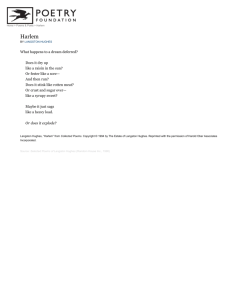

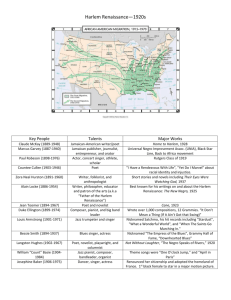

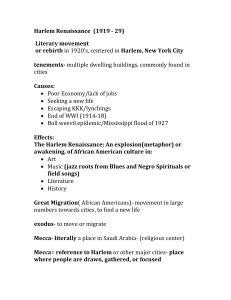

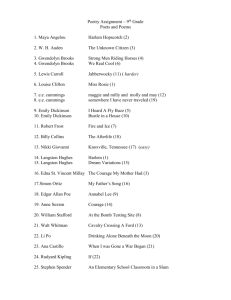

The Harlem Renaissance Mid 1920s – Mid 1930s Background/Harlem Renaissance The Harlem Renaissance refers to the flourishing of AfricanAmerican culture between the two world wars. In this period of cultural awakening, African-American literature, music, art, theatre, and political thinking were all energized. The movement developed from a new pride in blackness, an interest in African cultural heritage, and an appreciation of the folkways and creativity of rural and urban blacks. The movement has its roots in W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and his founding of the magazine The Crisis (1910); it developed with Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, founded by the National Urban League (1922) and edited by Charles S. Johnson. Harlem Renaissance cont. James Weldon Johnson called Harlem “the Negro capital of the world.” However, the movement is sometimes called the Negro Renaissance as Harlem was just one center of the movement. In 1926, Hughes published “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” an essay which provided the Harlem Renaissance with its manifesto as Hughes called boldly for both racial pride and artistic independence. “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame.” Langston Hughes criticized the black middle-class for ignoring their own culture in an attempt to appear elite: Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing the Blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near intellectuals until they listen and perhaps understand. Let Paul Robeson singing ‘Water Boy,’ and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem, and Jean Toomer holding the heart of Georgia in his hands, and Aaron Douglas’s drawing strange black fantasies cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty. Note to Stafford - self: Pause for Paul Robeson (but don’t embed it in the video, because it will not work with the override) Aaron Douglas, 1898 - 1979 Aaron Douglas, 1898 - 1979 “Douglas combined angular Cubist rhythms and seductive Art Deco dynamism with traditional African and African American imagery.” Harlem Renaissance: The Movement Poets like Claude MacKay, Countee Cullen, and Hughes reacted against the erudite, inaccessible poetry of Modernists and wrote more accessible poems. Hughes said that a poem “should be direct, comprehensible, and the epitome of simplicity.” The poetry of the Harlem Renaissance shuns sentimentality, didacticism, stilted diction, and romantic escape. The poets experiment with black speech patterns, verse forms, and rhythms, often inspired by jazz and the blues. Harlem Renaissance Continued Music was central to the flowering of the Harlem Renaissance. Jazz clubs such as the Harlem Casino, the Sugar Cane Club, and the Cotton Club entertained both black and white patrons. Harlem was home to Duke Ellington and Fats Waller. Whites comprised a substantial part of the audience. Whites were attracted to what they saw as the exotic in black life and black arts. Jazz and Blues During the Harlem Renaissance, blues and jazz gained in popularity with AfricanAmerican and white audiences. The blues is a music that originated in the Deep South. Descended from AfricanAmerican spirituals and work songs, the blues reflects the hardships of life and love in its lyrics. However, the blues can be humorous as well. The Major Literary Players in The Harlem Renaissance Writers central to the Harlem Renaissance include Jean Toomer, Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, and James Weldon Johnson. Toomer’s master work is Cane, which combined poetry and fiction in its depiction of African-American life. In their poems, Claude McKay and Countee Cullen condemned bigotry and racial injustice in often explosive language. Zora Neale Hurston developed fiction and theater based on her personal experience, her anthropological fieldwork, AfricanAmerican folklore, and Western mythology. However, at the center of the movement was Langston Hughes. Langston Hughes, 1902 - 1967 • Hughes dropped out of Columbia in 1922 and worked various jobs before working as a seaman and as a newspaper correspondent and columnist for the Chicago Defender, the Baltimore Afro-American, and the New York Post. In late 1924, he returned to live with his mother in Washington, D.C., where he worked first as an assistant to Carter G. Woodson at the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Dissatisfied with the work and lack of time to write, he quit. He then worked briefly as a cook at a fashionable restaurant in France and as a busboy in a Washington, D.C., hotel. It was there that Hughes left three of his poems beside the plate of a hotel dinner guest, the poet Vachel Lindsay, who recognized their merit and helped Hughes secure their publication. Hughes resumed his college studies at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and earned his B. A. in 1929. After graduation, he settled in Harlem, which he became his primary home for the rest of his life. Langston Hughes, cont. • Hughes was a prolific writer who worked in many genres: poetry, fiction, nonfiction, drama, musicals, and children’s books. As a popular newspaper columnist, Hughes created a fictitious Harlem narrator named Simple. • His life and travels are richly chronicled in his two volumes of autobiography, The Big Sea (1940) and I Wonder As I Wonder (1956). • His first poem was published at age 19, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in The Crisis, and his final book of poems, The Panther and the Lash: Poems of Our Times, the year of his death in 1967. • Deeply interested in developing a black theater, Hughes founded the Harlem Suitcase Theatre in New York in 1938, the New Negro Theater in Los Angeles in 1939, and the Skyloft Players in Chicago in 1942. • His life and work were enormously important in shaping the artistic contributions of the Harlem Renaissance. He wanted to tell the stories of his people in ways that reflected their actual culture, including both their suffering and their love of music, laughter, and language itself. “I explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America. This applies to 90 percent of my work.” – Langston Hughes