Judicial Review - Northern Illinois University

advertisement

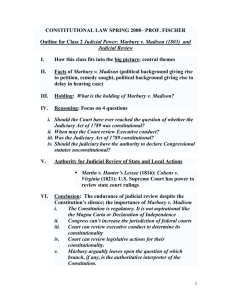

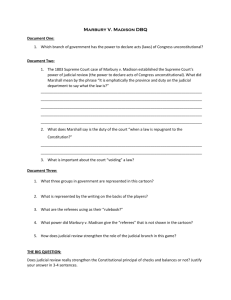

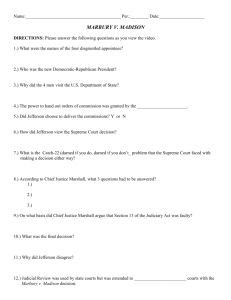

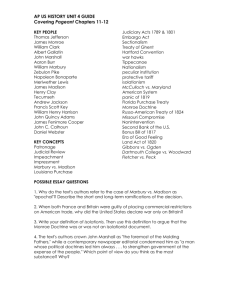

Judicial Review Stuart v. Laird, Marbury v. Madison and the Marshall Court’s Accommodation of the Jeffersonian Political Regime Elderhostel September 25, 2006 Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University Judicial Review: Opposition v. Accommodation Marbury is commonly presented as the origin of the story of judicial review and judicial power – particularly as the genesis of oldregime Federalist opposition to the new Jeffersonian political regime. However, when viewed in a larger context, Marbury exemplifies the Federalist Court’s capitulation to the Jeffersonian regime. Midnight Judges Having lost the election of 1800, the outgoing lame-duck Federalists (who still controlled the government) packed the federal courts by creating judgeships and filling them with Federalists. One of those judges was William Marbury. But Marbury never received his commission even though he had been nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The Repeal Act of March 8, 1802 Once they took power, the Jeffersonians reacted to the midnight judges by passing the Repeal Act, revoking the offices of judges who had been appointed with life tenure. Is this constitutional? The Jeffersonians also abolished the 1802 Term of the Supreme Court. In the House, impeachment proceedings began against Federalist District Judge John Pickering Marbury v. Madison (1803) James Madison At the close of the Adams administration, Secretary of State John Marshall forgot to deliver a few judicial commissions. William Marbury sued the new Secretary of State, James Madison, so that Marbury could be commissioned and begin serving as a judge. Article III and the Judiciary Act of 1789 Article III of the Constitution specifically details the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction. The Judiciary Act of 1789 gave the Supreme Court the ability to issue writs of mandamus – the power to order executive officials to perform particular duties. Can Congress expand the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction? Is Marbury entitled to his commission? Chief Justice John Marshall The framers intended the Court’s original jurisdiction to be exclusive. That is why the Constitution is very specific about which areas the Court has original jurisdiction: each one is listed. As a result, the mandamus section of the Judiciary Act of 1789 is unconstitutional. Still, Marbury was commissioned as a federal judge the moment the president signed and sealed the commission. The fact that it was never delivered or received is irrelevant. Marbury’s Significance For the first time, the Supreme Court struck down an act of Congress. Yet, by not ordering Secretary of State James Madison to deliver the commission, the Court was able to avoid a direct confrontation with the Jeffersonians. In the end, the Court had it both ways: it established judicial review, thereby constructing a powerful precedent for future cases; and it allowed the Jeffersonians to declare victory as they were not forced to comply with a Court order. Stuart v. Laird (1803) The Supreme Court refused to strike down the Repeal Act of 1802. Skirting the issue of whether the Constitution authorized Congress to abolish the circuit courts, Justice William Patterson held that Congress had the authority to transfer a pending case out of the circuit court once it repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801. This narrow/technical holding allowed the Repeal Act to stand. Impeachment & Removal A number of Jeffersonians wanted to impeach and remove Federalist judges. The ultimate goal was to remove Chief Justice John Marshall—the highest Federalist officeholder. They began with Justice Samuel Chase, an outspoken critic of the Jeffersonians. In the end, Chase was impeached but escaped conviction and removal by the Senate. The survival of Chase—and therefore Marshall—was a direct result of the Court’s accommodating decisions in Marbury and Laird. Justice Samuel Chase Conclusion The Supreme Court’s strength lies in its legitimacy in the eyes of the public and in its accommodation of national governing coalitions. The Court’s rulings in Marbury and Laird demonstrate strategic accommodation of a new political regime. Because of their capitulation, the Court proved strong enough to fend off Chase’s impeachment and continue to operate in the new Jeffersonian political regime, which lasted until 1832.