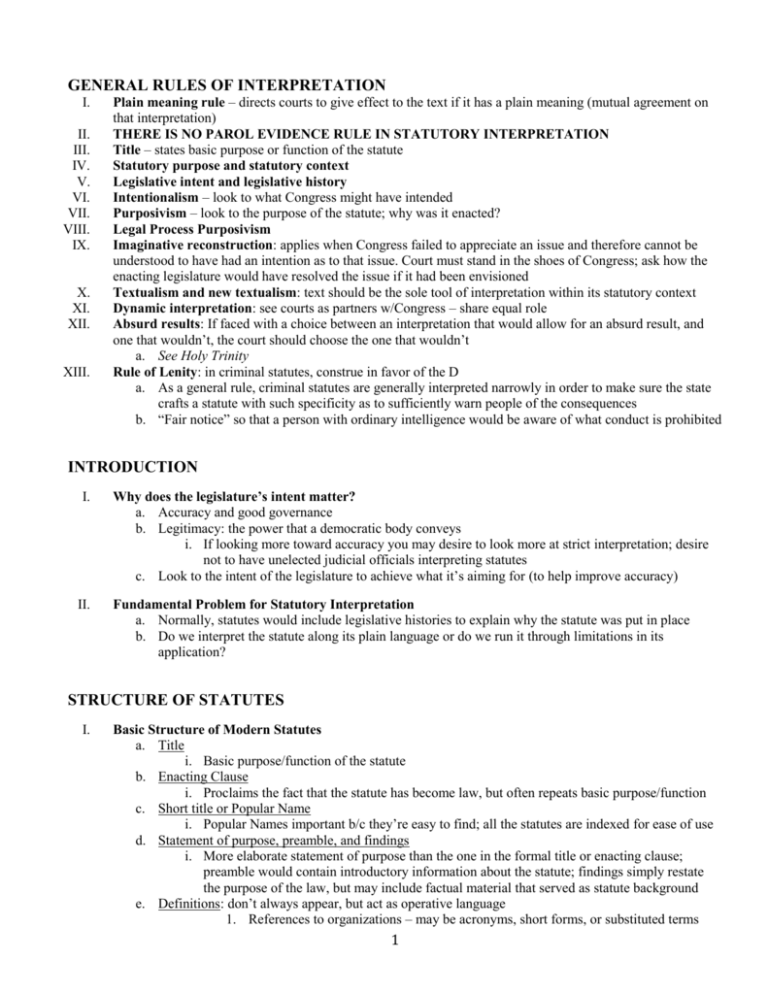

Statutory Interpretation A

advertisement