Law and Culture

advertisement

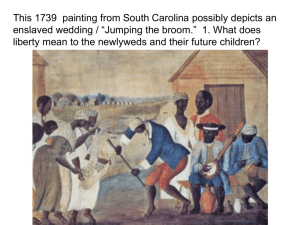

Zagreb Edward B Taylor "That complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society. According to Kroeber the consensus of most social scientists is that culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit of and for behavior acquired and transmitted by symbols constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups including their embodiments in artifacts ; the essential core of culture consists of traditional ideas and especially their attached values. Some sociologists exclude material objects from their definition of culture. They include technical knowledge about the artifacts. PAUL VALÉRY,‘L’EUROPÉEN’], PAUL VALÉRY, ‘THE EUROPEAN’ Partout où les noms de César, de Gaius, de Trajan et de Virgile, partout où les noms de Moïse et de St Paul, partout où les noms d’Aristote, de Platon et d’Euclide ont eu une signification et une autorité simultanées, Là est l’Europe.” .” : “Il est remarquable que l’homme d’Europe n’est pas défini par la race, ni par la langue, ni par les coutumes mais par les désirs et par l’amplitude “ de la volonté (…). “Wherever the names Caesar, Gaius, Trajan and Virgil, wherever the names Moses and St. Paul, wherever the names Aristotle, Plato and Euclid have a sgnificance and carry weight, that is where Europe is “It is remarkable that the people of Europe are not defined by race, nor by language or customs, but by desires and breadth of will (…)”. A HUSSERL LECTURE OF MAY 1935 ‘PHILOSOPHY AND THE CRISIS OF EUROPEAN HUMANITY “Es ist nun auch ersichtlich, dass von hier aus eine Übernationalität völlig neuer Art entspringen konnte. Ich meine natürlich die geistige Gestalt Europas. Es ist nicht mehr ein Nebeneinander verschiedener Nationen, die sich nur durch Handelund Machtkämpfe beeinflussen, sondern: Es ist ein neuer Geist, von Philosophie und ihren Sonderwissenschaften herstammend; ein Geist, freier Kritik und Normierung auf unendliche Aufgaben hin, er durchherrscht das Menschentum, schafft neue, unendliche Ideale!” One can also see that it’s the starting point of a new kind of community, one which extends beyond nations. I am referring, of course, to Europe in a spiritual form. It is now no longer a number of different nations living alongside each other and only influencing each other through commercial competition or power struggles, but it is: a new spirit – stemming from philosophy and the sciences based on it – a spirit of free criticism, providing norms for infinite tasks, and it dominates mankind, creating new, infinite ideals.” : “Europe’s existential crisis can end in only one of two ways: in its demise, alienated from its own rational sense of life, and lapsing into a hatred of the spirit and into barbarism; or in its rebirth from the spirit of philosophy, through a heroism of reason (…)”. national cultures themselves and of the close and complex relationships between these highly diverse cultures which ensure the cultural unity of Europe. Cultural identity and unity amid the diversity of national cultures does not amount to the simple indefinite expansion of an original cultural core. I see Europe’s cultural identity as a tightly woven fabric. This fabric consists on the one hand of a warp thread carefully stretched, which corresponds to the many strong national cultures, which themselves have their own identity and find their origins in a distant past; on the other hand, there is the weft thread, which represents the interwoven transnational bedazzlement and admiration, the reciprocal influences crossing the frontiers between cultures and between languages. I imagine this literary, artistic, linguistic, European cultural fabric as drawing its beauty, its unity and its solidity from the sheer number and diversity of its threads. Law and legal systems are cultural products like language, music, and marriage arrangements. They form a structure of meaning that guides and organizes individuals and groups in everyday interactions and conflict situations. This structure is passed on through socially transmitted norms of conduct and rules of decisions that influence the construction of intentional systems, including cognitive processes and individual dispositions. The latter manifest themselves as attitudes, values, beliefs, and expectations. According to their level and type of political participation and the nature of people's attitudes toward politics, Gabriel Almond and Sidny Verba outlined three pure types of political culture: Parochial - Where citizens are only remotely aware of the presence of central government, and live their lives near enough regardless of the decisions taken by the state. Distant and unaware of political phenomena. He has neither knowledge or interest in politics. In general congruent with a traditional political structure. Subject - Where citizens are aware of central government, and are heavily subjected to its decisions with little scope for dissent. The individual is aware of politics, its actors and institutions. It is affectively oriented towards politics, yet he is on the "downward flow" side of the politics. In general congruent with a centralized authoritarian structure. Participant - Citizens are able to influence the government in various ways and they are affected by it. The individual is oriented toward the system as a whole, to both the political and administrative structures and processes (to both the input and output aspects). In general congruent with a democratic political structure. These three 'pure' types of political culture can combine to create the ‘civic culture', which mixes the best elements of each Almond, Gabriel A., Verba, Sidney The Civic Culture. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1965. The concept "legal culture" figures often and prominently in the scholarship of the diverse disciplines of socio/legal studies. Political scientists, for example, use the concept to account for variation in the permissible legal delay in trials and in the behavior of judges and lawyers, as well as to explain differences in rates of litigation. Sociologists have found the concept useful for analyses of the ethics and practices of legal organizations. And anthropologists, using a more holistic approach, have characterized the legal cultures of entire societies. Indeed, this notion "legal culture" is one of the most general and ubiquitous concepts in the study of law and society. And as more and more nations from Central and Eastern Europe (and perhaps even to the eastern outskirts of Europe (e.g., Poland, Turkey) seek to join the European Union, the question of the diversity of legal values becomes all the more important for transnational legal policy. Furthermore, the structures of formal European legal systems vary; for example, the system is common law in Britain and Ireland, civil law in France and most of the Continent, with important (even if subtle) differences among those systems stemming from civil law traditions. Thus, it seems quite likely that the cultural values underpinning these systems differ as well. Although ours is only an initial foray into the structure of legal values in Europe, the importance of the issue may well justify the tentative nature of our efforts. JAMES GIBSON GREGORY CALDEIRA HTTP://WWW.JSTOR.ORG/PSS/3054034 1. Support for Rule of Law 2. Perceptions of the Neutrality of Law 3. Valuation of Individual Liberty LEGAL CULTURES IN EUROPE Law&Society Rewiew 30, 1, 1966 (1) legal consciousness, which refers to specific attitudes toward legal issues and institutions; (2) legal cultural values, by which we mean more general values relevant to the legal system but not necessarily closely connected to it; and (3) more general cultural values, such as a preference for individualism over collectivism, trust in people, Willingness to tolerate exceptions to the law is an attitude of some importance in the operation of a legal system. At the extreme, of course, nearly everyone agrees that there are some circumstances under which law must be put aside in favor of justice or self-interest or the need to craft immediate solutions to pressing political and legal problems. At the opposite end of the continuum, nearly everyone also believes that, in general, laws ought to be followed, that citizens and rulers have a normative obligation to abide by the rule of law, and that under most circumstances the universal and equal application of the law should prevail. But between these two extremes, there is a great deal of latitude, and it is this variability that is of most interest to us. The extent to which citizens believe that they ought to adhere rigidly to law is one aspect of legal values, and it is quite likely that nations differ significantly on this dimension. The best indicator of attitudes toward the rule of law is the third item: "If you don't particularly agree with law, it is all right to break it if you are careful not to get caught." This is a cynical statement that in essence cedes no moral authority to law. According to this item, the most law-abiding people are clearly the British—nearly 93% of the respondents disagree or disagree strongly with the statement. Similarly, in Italy, The Netherlands, Ireland, Denmark, West Germany, Spain, and East Germany, we find widespread disapproval of the idea that it is legitimate to break laws Conversely, respect for law is lowest in France, Luxembourg, and Belgium, where roughly one-quarter of the respondents agree or agree strongly with the statement (Portugal follows closely behind). There is certainly considerable crossnational variation within the EU in attitudes toward the rule of law There are comparable differences in perceptions of the neutrality of law. In West Germany and The Netherlands, more than 60% of the respondents reject the proposition that "My interests are rarely represented in the law; usually law reflects the views of those who want to control me." In Denmark, a majority of the respondents also rejects the statement; near majorities disagree with it in Great Britain, Ireland, and France. On the other hand, a majority of the respondents in Greece (and a near majority in Belgium) view law as a repressive force. In all our countries, sizable minorities, at least, assert that law reflects the interests of those who would control them. Thus, these perhaps surprising results suggest that belief in the neutrality of law is not necessarily widespread in Europe and illustrate significant cross-national variability. Various people may well perceive the role of law in society in quite different lights. This view of law as consensual and neutral is common within a variety of types of legal scholarship . Others, however, may perceive law as an external, repressive, and coercive force. Instead of embodying a broad social consensus to which nearly all citizens subscribe, law may be seen as an instrument of social control, as a means by which others advance their contrary political interests. This view of law as an instrument of political struggle, of political conflict, stands in sharp contrast to the perception that law represents the consensual interests of society. In the view that law in general represents the interests of the entire society and that few will express a fundamental alienation toward law and legal institutions. Earlier research has argued that a basic distinction among people is in their willingness to tolerate disorder for the benefit of individual liberty. This seems to be a basic social attitude, one stable over time and closely associated with a variety of other political beliefs. Moreover, struggles over the extent of individual liberty constitute the very heart of most legal systems. Those who value liberty are more likely to favor the universalistic application of the rule of law and are less likely to view law as an instrument of repression and social control. the subdimension of legal values, we find much more consensus. The best indicator of these attitudes— responses to the statement "It is better to live in an orderly society than to allow people so much freedom that they can become disruptive"—does not so clearly divide the countries of Europe as do the other items. In fact, the citizens of most of the countries endorse social order over potentially disruptive liberty. More than three-quarters of the respondents favor order in Portugal, Great Britain, and Ireland (and perhaps Luxembourg and East Germany as well). Only in The Netherlands, Italy, and Spain do we find at least 20% of the respondents expressing support for liberty on this item. The change of social rules: time and space Inseparable from modern state and rational-legal bureaucratic authority Aberation or rule? Necessary for functioning New forms and areas of regulation: conflict of interests, plutocracy, nepotism [Sociology is ] ... the science whose object is to interpret the meaning of social action and thereby give a causal explanation of the way in which the action proceeds and the effects which it produces. By 'action' in this definition is meant the human behaviour when and to the extent the agent or agents see it as subjectively meaningful In neither case is the 'meaning' thought of as somehow objectively 'correct' or 'true' by some metaphysical criterion. This is the difference between the empirical sciences of action, such as sociology and history, and any kind of priori discipline, such as jurisprudence, logic, ethics, or aesthetics whose aim is to extract from their subject-matter 'correct' or 'valid' meaning. – Max Weber The Nature of Social Action 1922, [5] The summary indicator of legal values suggests three major clusters of countries within the EU. At one extreme we find Greece, Belgium, Luxembourg, Portugal, and East Germany. These countries, regard for the rule of law is not strong, support for individual liberty is weak, and alienation from law is fairly common. Then, at the opposite end of the continuum lie Denmark, The Netherlands, West Germany, and Great Britain. The peoples of these countries tend to value individual liberty, to support the rule of law, and to reject the proposition that law is an external, repressive force. In the center, the cluster of Spain, Italy, France, and Ireland, somewhat mixed views prevail. Although there are important differences within these three clusters, we have some confidence that beliefs about law differ across these three major groupings of countries* The differences between the halves of the united Germany deserve special attention. West Germans seem to look favorably on law, and are at least somewhat positively oriented toward individual liberty. The East Germans, contrariwise, tend not to view law as neutral, value liberty less, and are not strong supporters of the rule of law. Like virtually all elements of the "unified" German system, there are substantial differences between East and West. One of the biggest issues in any legal system is compliance. Do citizens, organizations, and officials obey the law? Do they obey in conflictual situations? We do not have measures of the compliance or noncompliance of individuals. But we do have data on the compliance of European governments with the treaties of the European Union. The transnational character of the EU makes compliance an especially salient issue; and, accordingly, the EU relies on a number of procedures to bring about obedience to European law. Together with the Court of Justice, the European Commission serves as a bulwark of the integrity of the treaties, working to ensure compliance with the various forms of European law. Durkheim's believed that crime is "bound up with the fundamental conditions of all social life" and serves a social function. He stated that crime implies, "not only that the way remains open to necessary changes but that in certain cases it directly prepares these changes.“ He saw crime as being able to release certain social tensions and so have a cleansing or purging effect in society” "the authority which the moral conscience enjoys must not be excessive; otherwise, no-one would dare to criticize it, and it would too easily congeal into an immutable form. To make progress, individual originality must be able to express itself...[even] the originality of the criminal... shall also be possible". There is no society that is not confronted with the problem of criminality.Its forms changes; the acts thuse characterized are not the same everywhere; What is normal simply, is the existence of criminality, provided that it attaines and does not exceed… Crime is normal because a society exempt from it is utterly impossible Imagine a society of saints, a perfect cloister of exemplary individual …It is impossible for all to be alike… Legal definitions are not contradictory to each other. They are existing in pure world of logical dependencies and institutiond developed to overcome possibble disharmony. Real society is as living area of diaslectical change IS religion about ultimate reality? Is economy retional calculation means to an end? Is law an aplication to the fact to the legal proposition with acts of state as a consequence? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AV4- D-eTULY http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UjTHL i_kYVs&feature=related