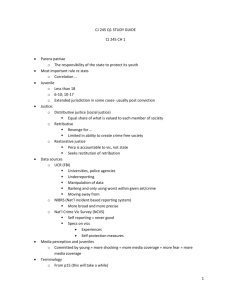

Chapter 21

advertisement

Part III STATUTORY AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, JAILS, JUVENILES, PRIVATIZATION, AND OTHER SPECIAL ISSUES IN CORRECTIONS Chapter 21 – Juveniles and Young Offenders Introduction: This chapter looks at the special considerations given in the criminal justice system to younger persons Chapter Outline Juveniles: History and Background Juvenile Court Concepts More Sophisticated Juveniles Kent v. United States In re Gault In re Winship Boot Camps Juveniles: History and Background Juveniles in the U.S. criminal justice system are treated under special rules designed for their protection – can be traced to English practices Juveniles: History and Background: cont’d English held that Children under the age of seven were irrebuttably presumed to be incapable of having criminal intent Between the ages of seven and 14, there was a rebuttable presumption of lack of criminal intent Over the age of 14, were presumed to be able to form criminal intent – could be rebutted by the person – and could be prosecuted as an adult Juveniles: History and Background: cont’d There also is the English concept of parens patriae – the monarch (the government) being the protector of the rights and welfare of the children Juvenile Court Concepts With time, the age of criminal responsibility was raised from 14 to 16, then to 18 In most states, 18 is the age when children are presumed to be adults and are held responsible for their criminal behavior Juvenile Court Concepts: cont’d Other legal concepts that have historically applied to juvenile court proceedings Juveniles not found “guilty” of “committing crimes” – act is one of delinquency, finding is one of delinquency; instead of “sentencing,” there is a “disposition” Juvenile court sits in protection of the welfare of the juvenile Juvenile Court Concepts: cont’d Juvenile court proceedings are much less formal Often closed to public attendance, to protect privacy of the juvenile Juvenile court sits in the position of judicial protector (guardian) of the rights, and best interests, of the juvenile Juvenile Court Concepts: cont’d Disposition of the case is based on the concern for the welfare of the juvenile Not sentenced to punishment; what is ordered is for the welfare of the child Cases are handled more quickly than those for adults The court proceedings are usually sealed Juvenile Court Concepts: cont’d Juveniles are not sent to prison – if placed in institutional care, these are training schools, residential facilities, juvenile homes, or of similar nature There is some movement towards more juveniles being handled in regular adult proceedings – from 1972 to 2000 the number of referrals of juveniles to adult or criminal courts increased over 500% Juvenile Court Concepts: cont’d Length of jurisdiction over the case is indeterminate Could be until person’s 21st birthday, or in some cases later Commitments to facilities are for shorter periods than for most adults Juvenile may be committed for an indeterminate time – release determined based on reports of his adjustment and betterment Juvenile Court Concepts: cont’d Three ways in which juveniles are brought before juvenile courts: Those charged with acts of delinquency – would be crimes if done by adults Status offenders – those who have violated societal rules that are not criminal for adults – example is curfew violation Dependent children – juveniles who have no, or deficient, family or support Foster parents or group foster homes may be used Juvenile Court Concepts: cont’d In 1999, over 1.6 million offenses disposed of by juvenile courts Most of the offenses were against property (42%) Over 23% of the juvenile offenders were female Over 65% of the petitioned cases resulted in the person being adjudicated delinquent, with another 0.8% transferred/waived to adult court Probation is most commonly used sanction for juvenile delinquents, especially for first offenders More Sophisticated Juveniles Ordinarily, “juvenile” refers to persons under the age of 18 As of 1999, in 10 states it is persons under the age of 17 In three states , it is persons under the age of 16 Can be exceptions - finding person is of sufficient maturity to be tried as an adult More Sophisticated Juveniles: cont’d Every state has a means for juveniles to be tried in adult criminal courts Traditional way - juvenile court holds a transfer hearing In 1998, 28 states automatically excluded cases from the juvenile system that met specific age and offense criteria More Sophisticated Juveniles: cont’d 15 states allow prosecutors to file certain juvenile cases directly in criminal court In all but four states, a juvenile court judge may elect to waive her court’s original jurisdiction over cases meeting certain criteria, and refer those cases directly to the criminal court More Sophisticated Juveniles: cont’d For the traditional transfer to adult criminal court, the court hears evidence, reviews reports and recommendations, and considers arguments on whether the juvenile is of such a degree of maturity or sophistication that the case should be heard in adult court If yes, the judge enters an order waiving the juvenile court’s jurisdiction over the juvenile Case is transferred to the local court of adult criminal prosecution More Sophisticated Juveniles: cont’d In the 1980s, there was a public perception that serious juvenile crime was increasing, and that the system needed to “get tough” In response, many states began to pass more punitive laws – 5 areas of change appeared in the 1990s Transfer provisions – 45 states passed laws to make it easier to transfer juvenile offenders to the adult criminal justice system More Sophisticated Juveniles: cont’d Sentencing authority – 31 courts gave criminal and juvenile courts expanded (tougher) sentencing options for juveniles Confidentiality – 47 states modified their laws to make juvenile records and proceedings more open Victim rights – 22 states expanded the role of victims of juveniles in the juvenile justice process Correctional programming – due to new transfer and sentencing laws, adult and juvenile correctional administrators developed new programs for juvenile offenders More Sophisticated Juveniles: cont’d In addition, some states modified the “purpose” clauses of their juvenile codes to Hold juveniles accountable for their criminal behavior Protect the public Recognize and balance the attention given to offenders, victims, and the community Impose punishment consistent with the seriousness of the crime Provide effective deterrents Kent v. United States (1966) In Kent v. United States (1966), the Supreme Court reviewed the rights of juveniles and the constitutional protections to which they are entitled Kent, age 16, broke into an apartment, stole a wallet, and raped the woman who was there He was interrogated by police (no counsel present) and admitted these offenses, and others His mother then retained counsel Kent v. United States: cont’d The juvenile court did not hold a hearing, nor talk to Kent, his mother, or his counsel The court did consider reports submitted by court staff, by social services, and by the probation section (Kent was already on probation) Kent’s counsel was denied access to the file being reviewed by the judge Kent v. United States: cont’d The Juvenile Court Act, under which the D.C. juvenile judge was acting, allowed waiver to adult court if the person was at least 16 and charged with an offense that would be a felony if done by an adult Could be done based on a “full investigation” by the juvenile judge Kent appealed from the order waiving his case to adult criminal court – District of Columbia courts denied his appeals Kent v. United States: cont’d At trial, Kent was found not guilty by reason of insanity on the rape counts He was found guilty on the other counts, receiving 30-90 years He was mandatorily committed to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for treatment on the basis of the insanity acquittals Kent again appealed his prosecution in adult court and the convictions Kent v. United States: cont’d U.S. Supreme Court held the transfer proceedings invalid; held that there must be some due process protections These include the right to a hearing, access by the person’s counsel to the reports used by the court in making the decision, and a statement of reasons for the court’s decision This was the first time the Court set minimum constitutional (due process) requirements for juvenile waiver proceedings In Re Gault (1967) The case of In re Gault involved a regular juvenile court case, and was not a transfer case (Kent) In Gault, a 15 year old was taken into custody by a county sheriff without notice to the boy’s parents When he was placed in a detention home, his mother was advised that he was being held for making an obscene phone call In Re Gault: cont’d At his juvenile court hearing the next day, the petition only said he was a delinquent minor At the hearing, an officer said Gault, when questioned, admitted to making lewd remarks on the phone Neither Gault nor his parents were advised of any right to counsel Gault was committed to the state industrial school for his minority (until he was 21) Gault’s parents filed a petition for habeas corpus – which was denied in the Arizona courts In Re Gault: cont’d The United States Supreme Court held for the parents – holding that Gault had been denied due process The Court said that delinquency proceedings must also include minimal due process protections Although not as extensive as adult criminal proceedings, these hearings require (at a minimum) In Re Gault: cont’d Advance written notice, to the juvenile and his parents, of the specific charges and the factual allegations that support the delinquency petition or charges The opportunity to be represented by counsel Availability of the privilege against selfincrimination And, absent a valid confession, a determination of delinquency and an order of commitment must be based on sworn testimony, subject to the opportunity for cross-examination In Re Winship (1970) In re Winship dealt with the standard of proof required in juvenile proceedings In the case, a 12 year old boy was found to have stolen $112 from a woman’s purse Petition charging the boy with delinquency alleged that if done by an adult, the crime would have been larceny Governing New York law held that any finding that a juvenile did an act or acts must be based on “preponderance of the evidence” In Re Winship: cont’d Winship was ordered to be placed in a training school for 18 months, subject to possible annual extensions until his 18th birthday (six years later) The Supreme Court held that, for criminal cases, a guilty finding requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt, a higher standard than preponderance of the evidence Court held that juveniles are constitutionally entitled to the higher standard when charged with the equivalent of a criminal law violation In Re Winship: cont’d The Court rejected the contrary arguments of the New York Court of Appeals That the delinquency adjudication was not a conviction That the juvenile proceedings were not designed to punish, but to “save” the child That to impose the higher standard would risk “destruction” of the beneficial aspects of the juvenile process In Re Winship: cont’d That to allow the child to prevail was probably not in the best interests of the child And that there was only a tenuous difference between the two standards On this, Supreme Court commented that the trial judge had acknowledged that the proof might not meet the higher standard In Re Winship: cont’d The Court held that the constitutional safeguard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt was required, that “where a 12-year old child is charged with an act of stealing which renders him liable to confinement for as long as six years, then, as a matter or due process . . . the case against him must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt” Boot Camps Sometimes called “shock incarceration” Special type of sentencing – at times referred to as intermediate sanctions or alternative sentencing Boot camps emphasize military drill, physical training, and hard labor Geared to young, male offenders, sentenced for nonviolent offenses Earliest currently operated correctional boot camp program dates to 1984 Boot Camps: cont’d Stay in boot camp is intended to be short Daily life is long and hard, heavily structured Boot camps are also used for juvenile delinquents Military style uniforms, march to and from activities, respond quickly to the orders of the “drill instructors” Daily schedule – may include drills and ceremony practice, physical fitness activities, challenge programs, academic education; misbehavior may be handled by summary punishment Boot Camps: cont’d In one sense, boot camps replaced the specialized treatment of youth offenders Boot Camps: cont’d Boot camp proponents say boot camps Are cheaper to run, and thus reduce costs Help to reduce crowding in regular prisons Are seen by judges, legislators, media, and the public as tougher treatment of offenders, and thus as more fitting punishment Help to rehabilitate the offender Deter future crime and reduce recidivism Boot Camps: cont’d Underlying concept of boot camps, as in the earlier specialized programs Concentrating on persons of younger age, who are not criminally sophisticated and not entrenched in criminal careers, will produce results, because they are still amenable to treatment programs and change Boot camp program teaches respect for authority, self-discipline skills, accountability, pride in achievements, self-esteem, and good work habits Boot Camps: cont’d Evaluation of these arguments for boot camp brings mixed results Because of shorter terms, there are overall cost savings Demand for regular prison beds is reduced As to rehabilitation/reduction of recidivism, studies don’t show a significant difference from traditional prison programs Boot camp concept still relatively new, and evaluation of them will have to continue Boot Camps: cont’d Thus far, few legal challenges to the conditions of boot camp facilities and programs Because boot camp program is perceived as providing some advantages – shorter terms, special programming, and early return to homes and family – the main legal questions are ones of parity Boot Camps: cont’d Does the sentencing or the opportunity for the program benefits discriminate Against women offenders Against disabled persons Against older offenders or others who are excluded by the definitions of boot camp eligibility Boot Camps: cont’d It is expected that whether a state can justify the distinctions and the grounds for discrimination will be explored in future litigation Correctional administrators are advised to examine their resources prior to any legal challenge Boot Camps: cont’d The examination should include such issues as The number of persons who would be included if the programs were expanded to include others Whether the programs could include more offenders And whether females, disabled offenders, or wider categories of offenders in age or other criteria might be included in the programs by special accommodations or other steps