Macbeth - English Department

advertisement

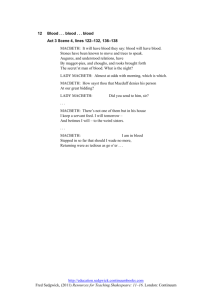

Macbeth First lecture Professor J. Sears McGee, of history department • Second of our series of Renaissance Studies faculty presenting work on the context of Shakespeare’s Jacobean plays. • Prof. McGee teaches Tudor and Stuart history, has written on Anglican and Puritan constructions of godliness in the period and on religion and kingship. • Check out Renaissance Studies at <english.ucsb.edu/faculty/oconnell/renstudies> “The Scottish Play” • There’s an actors’ superstition that you must never say the name of the play or mention either of the Macbeths by name in a theater – unless you are speaking the lines of the play in performance or rehearsal. • Instead you refer to “the Scottish Play” and “the Scottish gent” or “Lady M.” • If you slip, you must turn around three times, spit or break wind, leave the room and knock to enter. • Or you can quote Hamlet: “Angels and ministers of grace defend us!” • Some companies might impose a fine. • Moreover, the play is considered unlucky. Lots of accidents and deaths associated with performances of the play. • Lincoln was reading the play in the week before he was assassinated. • The tradition supposedly begins as early as August 7, 1606, when a boy actor named Hal Berridge who was to play Lady M. took sick and died in the theater. • (But there’s absolutely no documentary record to confirm this urban legend; in fact no actual record of the play’s performance until 1611.) • And no record of Hal Berridge. Still, you can’t be too careful . . . • Superstition may come from the witches curses? • And a play with sword fighting has its perils. • BUT could the superstition come from our sense that this is a play that deals seriously with evil? • More than any other of Shakespeare’s plays, Macbeth seems to be about the genesis of evil. • We see a man becoming evil – and by his own volition. • The play is steeped in blood from the very beginning. • “What bloody man is that?” Duncan asks (I.2). • And the “bloody man” recounts a story of blood. • Macbeth “unseamed” the “merciless Macdonwald” “from the nave to the chaps/ And fixed his head upon our battlements” (I.2.22-23). • And evokes a scene in which Macbeth and Banquo “bathe in reeking wounds,/ Or memorize another Golgotha” (39-40). • And this is all “good” bloodshed, done in the defense of Duncan. Macbeth’s indecision • We need to decide what the relation is between Macbeth’s ambition and the prophecy of the witches. • What meaning do the witches have for Mac’s state of mind, his future actions. • But we won’t answer that yet. • Note the non-committal nature of the letter he sends to Lady Mac at I.5. • She worries he may not have the guts to carry out what she believes should be carried out to make the prophecy come true. • He’s “too full of the milk of human kindness/ To catch the nearest way.” • No question of her decision about what should happen to make Macbeth king: her soliloquy at I.5. 36ff. • Mac’s only response: “we will speak further.” Why does Macbeth want to be king? • His soliloquy at I.7: note his backward statement about jumping the life to come. • But even the judgment here persuades against the assassination. • The image that may make us recall Hamlet: the poisoned chalice forced “to our own lips.” • Duncan is Macbeth’s guest “in double trust.” • And Duncan’s kingship gives no reason for assassinating him. • The image of pity, “like a naked newborn babe.” • So where does the impetus for the murder come from? • Note the unfinished sentence. Lady Macbeth’s persuasive image! • Her appeal to his manhood: a real man would do this. • “I have given suck . . .” (I.7.54ff) • An image that corresponds to Macbeth’s simile for pity? • Why should this image persuade? • Image of mother and child turned to nightmarish image of horror. • In every case, it’s the image of helplessness that somehow stimulates the desire to kill. • Because we can do it, we should do it. • Lady M’s statement (II.2) that she’d have done the murder herself “Had he not resembled/ My father as he slept.” Banquo’s dreams • II.1: he wants to sleep, but is afraid to dream. Why? • And he hands over his sword – and dagger? • He has dreamt of the “weird sisters.” • Does he want to? Why? • Acceptance or rejection of a “dream.” • And his response to Macbeth’s invitation to talk over “that business.” • And by contrast Macbeth’s “dream”: “Is this a dagger I see before me?” • “a dagger of the mind”: with a double meaning? • And then the dream-state dagger becomes covered with blood. • What does one do with a nightmare or a vision of horror? Thinking brainsickly • Lady M accuses Macbeth of unbending his noble strength “to think so brainsickly of things” (II.2.48-49). • Because he imagines that in killing a sleeping man, he has killed sleep. • “Innocent sleep”! And six wonderful metaphors for sleep. • And his anxiety over not being able to pronounce “Amen” to the guards’ “God bless us.” • “Consider it not so deeply.” • But why couldn’t he respond? • And why will his hands “rather the multitudinous seas incarnadine/ Making the green one red” instead of washing off the blood? • While she insists, “A little water clears us of the deed.” • The vast gulf between them?