A Workshop on Teaching - Tamu.edu

advertisement

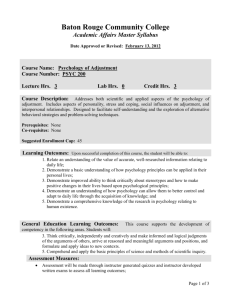

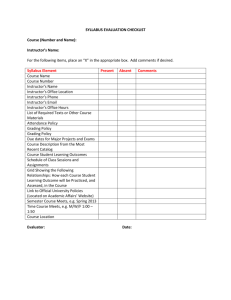

A Workshop on College Teaching and the Teaching of Psychology Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Texas A&M University May 14-17, 2012 http://people.tamu.edu/~lbenjamin “Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.” George Bernard Shaw “Those who can’t teach, teach gym.” Woody Allen A Whirlwind Tour: 17 Topics • • • • • • • • • 14-Teaching resources 14-Goals 14-The syllabus 14-First day of class 15-Lecture method 15-Active learning 15-Discussion methods 16-Evaluation methods 16-Grading • • • • • • • • 16-Class management 16-Advising, mentoring 17-Writing 17-Computer technologies 17-Media 17-Large classes 17-Team teaching 17-Evaluation of teaching My Goals for This Workshop • Make you familiar with the multitude of resources on teaching psychology • Acquaint you with some of the dos and don’ts of various teaching and evaluation methods • Provide you with some tips on classroom management issues • Add to your repertoire of active learning exercises • Expand your confidence as teacher and your commitment to your students • Save you time in teaching preparation, grading, and dealing with classroom problems This Workshop Should Help You If • You teach courses as a graduate student • You pursue a career as an academic • You are required to make case presentations (as in clinical psychology) • You are required to sell your management, research, or organizational ideas to industry • You have a job interview where you have to sell yourself • You have to communicate your ideas in any setting College and University Settings • Research 1 universities (60-30-10) • State universities • Private universities • Liberal arts colleges • Two-year colleges • Professional schools • • • • • • Teaching loads Teaching expectations Who teaches Class size Student expectations Student abilities Teaching is Important • Most of us are in academia because of a teacher • We work in a privileged environment • We have obligations to our students • Making a difference in the academic world • Teaching skills are not genetically based • There is a teaching literature • We should want to get better at what we do Four-Day Outline May 14: Literature of Teaching, Goals, Syllabus, First Class Day May 15: Lecture, Active Learning, Discussion May 16: Evaluation, Grading, Classroom Management, Advising/Mentoring May 17: Writing, Computers, LGI, Team Teaching, Course Evaluation May 14 – Monday 9:00-10:15 A Teaching Literature Goals – Part I 10:35-11:50 Goals – Part II The Syllabus First Class Day I. Teaching Resources • Generic college teaching books • Specialty books, e.g., construction of exams, grading, lecturing, teaching large classes • Teaching of psychology books • Psychology activity books – general and specific • Teaching of psychology journals • Teaching of psychology conferences • Society for Teaching of Psychology website • TAMU Center for Teaching Excellence (GTA) II. Course Goals: This Is Always Where You Start Goals: Overview • Learn the academic culture • Goals should determine everything you do in your course • Selecting, implementing, and assessing your goals • An exercise in choosing course goals • Two examples of implementing goals Learn the Culture • Every college/university has a culture • There is also a departmental culture • Are there multiple sections of the course you will teach? • Is your course a prerequisite or postrequisite for another course? • Student expectations for your class Course Goals Should Determine Virtually Everything That You Do in Your Course • Determines textbook selection, or whether you even use a book (topical, chronological, theoretical or philosophical orientation, breadth/depth, etc.) • Other reading assignments • Writing components • Evaluation methods • Classroom instructional methods Course Goals • Selecting them • Selling them • Implementing them • Measuring them Course Goals: An Exercise College Professors’ Responses 11 Content 3 2 1 8 15 Scientific Processes Psychology and Society Educational Preparation Scientific Values Critical Thinking Introductory Psychology Students’ Responses 12 Self Knowledge and Understanding 10 Study Skills 9 Social and Interpersonal Skills Goal: Integration of Introductory Psychology Chapters Create a mini-course within the introductory psychology course A few examples Sleep and Dreaming Biopsych – Neurotransmitters in sleep Perception – Awareness of stimuli by sleep stage Learning – Debunking sleep learning Memory – Dream recall Personality – Long vs. short sleepers Abnormal – Night terrors, sleep walking, depression Developmental – Ontogeny of sleep & dreaming Social – Cultural effects on sleep Industrial/Organizational Psych Biopsych – Circadian rhythms and shift work Perception – Attention and vigilance in workplace Learning – Training Cognition – Teaching creative thinking Motivation – Job satisfaction, burnout Development – Older workers, retirement Personality – Management and leadership styles Social – Organizational climate Goal: Help Marginal or New Students • • • • • Improve attendance Help students keep up with the reading Help students regularly review their notes Help students learn what is important to know Help students study throughout the course The Kingsfield Procedure • • • • • Class should not be larger than 50 students Index card for each student 5 to 10 questions each day Point system Cheating! (to make it fairer) Kingsfield Outcomes • Professor learns names • Attendance is excellent; students are not tardy • Students do their reading on time and regularly review their notes • Students learn what the instructor considers important • Students learn some critical thinking skills • Grades are higher • Student opportunities for questions vary • Students rate the procedure quite positively III. The Syllabus: It’s a Contract This agreement is entered into this 14th day of May, 2012 by and between Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr., hereinafter referred to as the Professor, and _______________, hereinafter referred to as the Student. Whereas the Professor has covenanted and agreed with Texas A&M University, Department of Psychology, to utilize his experience, training, education, and best efforts towards instructing the Student in the subject of Introductory Psychology, and whereas the Student is desirous of gaining as much knowledge, training, insight, and understanding as possible; NOW THEREFORE, for and in consideration of mutual promises contained herein, the parties promise, covenant, agree, warrant, and make the following representations…. (from Stanley Freeman, U of South Carolina ) The Syllabus: Overview • • • • The syllabus as contract What should be in a syllabus? Syllabus contents Distributing your syllabus to students What Should Be In a Syllabus? How Lengthy Should It Be? Syllabus Contents • Course number and title, instructor name, semester and year, office location and hours, office phone number, email and website addresses • Textbook(s) – required or recommended • Course goals • Assignments and evaluation policies; make-ups • Course outline • Attendance policy (def. of excused absences) • Class rules (on time, cell phones, respect for others) • Statement on cheating, including plagiarism • Required university statements From TAMU Rules (2012) Rule 10.1 – The course instructor shall provide in writing the following information to the class during the first class meeting: • A statement of the nature, scope and content of the subject matter to be covered in the course. • All course prerequisites as listed in the catalog. • All required course text and material. • The grading rule, including weights as applicable for tests, laboratory assignments, field student work, projects, papers, homework, class attendance and participation and other graded activities in the calculation of the course grade. Getting the Syllabus to Students • In class • In a course packet • Have them download it from your website • Emailing to them in advance of the course (it must be uploaded in Howdy re State law) IV. First Class Day • First impressions matter • Go over the syllabus – goals, rules, assignments, evaluation methods • Hook them on your material – get them excited for what is to come • Spend at least some time in that first meeting on content • Introduce yourself – professionally and personally The Autobiography Due 2nd class period, 1-3 pages • Name, email, home (cell) phone number • Where born and grew up • About your family • Interests in high school, both in school and extracurricular • Why you came to Texas A&M • Your major and why you chose it • Why are you taking this course and what do you hope to get from it? • Hobbies, jobs • Plans after graduation from TAMU Use of the Autobiographies • • • • • • If it’s a small class – 2nd day introductions Learn about my students Use the material to personalize some classes Personal emails back to the students Re-read them before students come to see me Assign paper topics based on that information Other First Day Activities Wear a hood with one eyehole. Periodically make gurgling noises. Gradually speak softer and softer and then suddenly point to a student and scream “YOU! WHAT DID I JUST SAY?” Announce “You will need this” and then write the suicide prevention hotline number on the board. If someone asks a question, walk silently over to their seat, hand them the chalk, and ask “Would you like to give the lecture Mr. Smartypants?” Start the lecture by dancing and lip-syncing to James Brown’s “Sex Machine” Have a student sprinkle flower petals ahead of you as you pace back and forth. Stop in mid lecture, frown for a moment, and then ask the class whether your butt looks fat. Jog into class, rip the textbook in half, and scream, Are you pumped? ARE YOU PUMPED? I CAN’T HEEEEEAR YOU!” by Alan Meiss (Indiana University) May 15 – Tuesday 9:00 – 10:15 The Lecture Active Learning I 10:35-11:50 Active Learning II Discussion Methods V. The Lecture Method Four Questions • Why lecture? • Should you lecture? • What should be your lecture style? • What are the components of a good lecture? Why Lecture? Lectures can provide integrative and evaluative accounts…(reducing an unselected vastness to a manageable form) that may not be available in any printed or electronic version. Lectures can be models of critical thinking and problem solving that can teach students higher cognitive skills. Further, lectures have motivational functions. By challenging students’ beliefs, lectures can motivate students to pursue further learning. (Benjamin, 2002; McKeachie, 1999) Should You Lecture? • Audience expectations • What is it you want to do? • The nature of the information to be communicated • Class size • Is lecturing a strength for you? • What can lectures do? Model, inspire, provoke, summarize, synthesize, evaluate, communicate cutting-edge work The Lecture and the Textbook • Textbooks are usually encyclopedic • TAMU students are typically bright and can read on their own • So why go over in excruciating detail the material they are supposed to have read on their own? • The lecture is about your freedom to choose • It is often a chance for depth What Should Be Your Lecture Style? • Your personality (UCLA Chemistry Dept.) • Formal or informal (more interactive) • Problem oriented “The most effective performing is not a contrived act, but a genuine, authentic presentation of the person involved. If the role to be played is the person you are, you don’t need to fear being false or not being up to the part.” Maryellen Weimer (1998) Components of a Good Lecture • • • • • • • • • • Enthusiastic (maybe even passionate) about the material Clear objectives for the lecture Advanced organizers In-lecture summaries End-of-lecture summary Clear organization Good examples Less is more (depth, rather than breadth) Active learning Allow for digressions from students Lecture Outline: Psychological Theories of Love 1. Overview of three theories 2. Attachment theory a. Supporting research b. Summary 3. Lee’s Six Types of Love a. Supporting research b. Summary 4. Sternberg’s triangular theory a. Supporting research b. Summary 5. Overall summary VI: Active Learning -- Defined Active learning describes an array of learning situations in and out of the classroom in which students enjoy hands-on and minds-on experiences. Students learn through active participation in simulations, demonstrations, discussions, debates, games, problem solving, experiments, and writing exercises. Active Learning – An Overview • What can it do? • What should good active learning exercises do? • Where can you find active learning exercises? • Some examples Active Learning… • • • • • • • • • is underused is an excellent supplement to lectures increases student involvement increases cognitive demands produces elaboration of meaning (deeper processing – better retention) is excellent for experiential topics can help problematic lecture or book topics adds enjoyment to the class can take a little class time or a lot Active Learning Exercises Should • • • • • be practiced educate, motivate, perplex your students involve all students teach one or a few key points be assessed to see if students are learning what is intended Where Can You Find Active Learning Exercises? • • • • • Your own experiences Teaching of Psychology journal Activity books (see my website) Teaching conferences and symposia On the Web (particularly STP website) Active Learning Some Examples Learning to Read Active Learning Examples in… • • • • • History Statistics Biopsychology Sleep and Dreaming Sensation and Perception • Learning • Memory • Motivation • Developmental Psychology • Gender • Diversity • Psychological Testing • Personality • Social Psychology • Abnormal Psychology • I/O Psychology VII. Discussion Methods When measures of knowledge are used, the lecture is as efficient as other teaching methods. However, when the dependent variables are “measures of retention of information after the end of a course, measures of transfer of knowledge to new situations, or measures of problem solving, thinking, or attitude change, or motivation for further learning, the results show differences favoring discussion methods over lecture.” McKeachie (1999) Discussion Methods -- Overview • • • • • What is the optimum class size for discussion? What discussion does Problems in using discussion Other issues in using discussion Examples What is the optimum class size for discussion? What Discussion Does • Helps students articulate what they have learned • Gives instructor a good idea of student understanding • Gives students opportunities to apply what they have learned • Helps students learn to evaluate the logic of and evidence for their own and others’ positions McKeachie (1999) Problems in Using Discussion • Getting a discussion started • Identifying a clear objective(s) for the discussion • Dealing with a discussion monopolizer • Getting reluctant students to participate • Students revealing too much • Students attacking the ideas, beliefs, attitudes, of other students Discussions – Other Issues • Class size – Making smaller groups (buzz groups, jigsaw groups) • Time required • Willingness to give up class control • Providing a focus – Problem solving – Structured questionnaire (example) What is Aggression? See Handout May 16 -- Wednesday 9:00 – 10:15 Evaluation Methods 10:35 – 11:50 Grading Class Management Advising, Mentoring VIII. Evaluation Methods Overview • Types of assignments and tests • Functions of tests • Types of tests – Construction dos and don’ts Types of Assignments and Tests • • • • • • • • • • abstract advertisement annotated bibliography biography briefing paper brochure, poster budget, with rationale case analysis chart, graph, visual aid cognitive map • • • • • • • • • • court brief debate definition diagram, table dialogue diary essay executive summary fill-in-the-blank flowchart Classroom Debates Assign students to teams (N=4) and to pro or con sides • Breast-fed babies are physically and psychologically healthier than bottle-fed babies. • The earlier a child starts school the better. • There should be a national child-rearing licensing law that requires parents to take parenting classes. A Debate Format (75-min class) Moderator and two panels • Opening Statements – Pro Side (3 mins.) – Con Side (3 mins.) • Closed Panel Discussion (35 mins.) • Open Discussion – Class asks questions (20 mins.) • Final Arguments – Con Side (5 mins.) – Pro Side (5 mins.) Assignments & Tests (continued) • • • • • • • • • • • group discussion instructional manual introduction inventory laboratory or field notes letter to the editor matching test mathematical problem memo multimedia presentation narrative • • • • • • • • • • • news story, newspaper oral report outline personal letter poem, play project plan question regulations, laws, rules research proposal review of book, article review of literature Newspaper Assignment in Undergraduate History of Psychology • • • • • Years are randomly assigned 4-pages of content Psychology in context Graded on content Poster session (I bring treats) And More … • rough draft • statement of assumptions • summary • taxonomy • technical or scientific report • term paper • thesis sentence • word problem from Walvoord & Anderson (1998) • • • • • • • • • • • grant proposal oral exam lab practical true-false exam two-minute paper journal reaction paper personality test psychology “Jeopardy” class participation extra credit Personality Test in PSYC 107: Two Classes Honesty Friendliness Loyalty Self-esteem Tolerance Aggressiveness Independence Optimism Confidence Friendliness Creativity Caring Responsibility Aggressiveness Sense of Humor Ambition Student Generated Items • I would not betray a friend under any circumstances. • I enjoy associating with people who are different than me. • When I am working on a project, I would prefer to work by myself. • My friendliness is greatly dependent upon what happens to me. • My future will be a happy one. Functions of Tests • Evaluate students and assess their learning • Help instructor assess how well he/she is presenting the material • Communicate to students what they have and have not mastered • Motivate students to read and study assigned material • Assess whether goals are met, and how well (from Davis, 1993; McKeachie, 1999; Benjamin) Types of Tests • • • • • True-false Fill-in-the-blank Matching Multiple choice Essays True-False Tests • Items seem easy to write (but aren’t) • Typically too much ambiguity • Guessing is a problem. What correction formula do you use? • Psychometricians say AVOID THIS KIND OF TEST ITEM • If you use them, have students write out their reasons • And don’t get cute! Fill-in-the-Blank Tests • I call these “Guess what the professor is thinking” tests • Difficult to write items that are not ambiguous • Avoid them – there are far better kinds of tests Matching Tests • Allows many questions to be asked in a limited amount of time • Don’t make them too long. 10-12 items is about right • Have the set of alternatives (column 2) longer than the items in column 1 • Problem with this test is that students may make correct associations from memorization but not know meaning, e.g. Darwin-natural selection Sample Matching Test ___ Ludy Benjamin ___ Dick Cheney ___ Lamont Cranston ___ Aretha Franklin ___ Fred Rogers 1. A clown 2. Champion marksman 3. Governor of Texas 4. Liked us the way we are 5. Old guy 6. Queen of Soul 7. The Shadow 8. Ben Franklin’s mother Multiple-Choice Tests • The cornerstone of most standardized tests – FOR A REASON • Educational Testing Service (ETS) – 5 alternatives – they never use all of the above or none of the above – they have impressive statistics on any item that makes its way into one of their tests – they order their items from least to most difficult Good Multiple-Choice Items • • • • Essence of the question should be in the stem Avoid negative statements Alternatives should be roughly the same length Avoid words in the alternatives that might be keyed from the stem • Distractors should all be plausible • Distractors should include common knowledge and thinking errors Good Multiple-Choice Items • Are time-consuming to write • You should get better over time in eliminating the confusion and ambiguity in your items, especially if you reuse items • Are in scarce supply in publishers’ test manuals – BE VERY CAREFUL M-C Items – Other Issues • How many? Some people use the rule of thumb of one per minute. • Correction formula? • M-C tests allow you to sample the content domain quite broadly • If you reuse items, do item-total correlations to evaluate your items (is an item that was answered correctly by 10% of the students a good item?) • Consider letting students write on their exams for items they find ambiguous Answer Changing One of your students asks you, “Should I ever change my answers on a test?” How would you respond? Benjamin, L. T., Jr., Cavell, T. A., & Shallenberger, W. R. (1984). Staying with initial answers on objective tests: Is it a myth? Teaching of Psychology, 11, 133-141. Essay Questions • Measures retention by recall as opposed to recognition • Less objective scoring when compared to most other test types • Ways to mask student identity • Use a rubric for scoring (greater consistency, faster grading) • Score same question for all exams before scoring second essay • Do not give choices on essays (comparability issues) Sample Essay Question Dr. Ramirez believes that first-year college students who are assigned a senior mentor for the year will perform better academically and feel more positively about their college experience than those students who go through the first year without a mentor. Design an experiment to test this claim. Operationally define the key terms. Describe the controls that you would use and a method that you would use to evaluate the outcome of your study. In your answer you should include a description of each of the following: subject selection and sample size, independent variable(s), dependent variable(s), experimental group, control group, potential confounding variables (at least two), method of reducing experimenter bias, and method for analyzing the data. Be sure to label independent and dependent variables and control and experimental groups. (20 points) Scoring Rubric 1 1 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 Subject selection (randomization, sample characteristics, at least 20 per group) Independent variable label: senior mentor program Independent variable definition Dependent variable 1 label: academic performance Dependent variable 1 definition Dependent variable 2 label: attitudes about school Dependent variable 2 definition Experimental group(s) Control group(s) Confounding variables: name at least 2 Reducing experimenter bias: blind control, computer scoring, etc. Evaluation of results: statistically significant differences, use of inferential statistics Essay Questions Can Measure… • • • • • • Knowledge Comprehension Application Analysis Synthesis Evaluation Make-Up Exams • Obey the university rules • Do not penalize students who have university recognized absences • What about students who do not have legitimate excuses for missing an assignment? IX. Grading - Overview • • • • Where to begin Functions of grades Grading issues The mechanics of grading Where to Begin • Know the official rules at your university/college • Know the (informal) unofficial rules in your department • Grading practices should be tied to the goals for your course • Communicate your grading criteria clearly, ideally in your syllabus (see TAMU rules) Grades According to TAMU Rules Rule 10.3 – The five passing grades at the undergraduate level are, A, B, C, D and S, representing varying degrees of achievement; these letters carry grade points and significance as follows: Assigned by the instructor: • A: Excellent, 4 grade points per semester hour • B: Good, 3 grade points per semester hour • C: Satisfactory, 2 grade points per semester hour • D: Passing, 1 grade point per semester hour • F: Failing, no grade points, hours included in GPR Functions of Grades • • • • As communication devices (currency) As indicators of student performance As indicator of student’s potential in your field As rewards (punishers?) Grades are important to students, admission committees, professors, employers, etc. Issues in Grading • • • • • • • Grade inflation Mastery grading Contract grading Grading on the curve Satisfactory/Unsatisfactory grading Extra credit First-year grade exclusion of up to 3 courses with D or F (TAMU) The Mechanics of Grading • • • • • • • • • Objectivity Scores versus grades Scaling exams Cut-off scores (revealing cut-off scores) Incomplete grades Checking your final calculations, rechecking Posting grades Changing grades Deadlines and penalties Grades in PSYC 107 (Fall 1990) A 12.8 5.7 17.5 7.5 4.5 12.3 5.1 5.1 B 46.4 38.9 40.6 29.2 30.9 23.8 29.0 20.8 C 34.7 43.6 32.5 42.0 44.1 35.4 40.6 49.1 D 4.1 9.5 14.6 17.5 17.3 24.1 20.3 21.0 F 2.0 2.4 4.7 3.8 3.2 4.5 5.1 4.2 GPA 2.638 2.360 2.316 2.193 2.164 2.153 2.088 2.014 Grading Situation #1 Your syllabus indicates that an A is earned for students who score 450 points or better out of a possible 500. A student comes to visit you after the final exam who has earned 444 points. The student argues that the percentile score is 88.8 and that is so close to a 90 that it should be an A. What would you do? Grading Situation #2 A senior is taking a summer course from you who is planning to graduate in August and her parents have bought their plane tickets for graduation. But the student is making a D in your class and has no hope numerically of scoring high enough on the final exam to make a C which she needs to graduate. She pleads with you for a C. What would you do? Grading Situation #3 A student recently made a grade of “F” on your exam. The student was quite sick the morning of the exam but decided to take the exam anyway. Now he thinks that strategy was a bad idea. He comes to you and explains the situation and asks for a grade adjustment or a make-up exam. What would you do? Grading Situation #4 A student in her first semester at Texas A&M earns a grade of C in your PSYC 107 course. She comes to see you after the grades are filed with the registrar asking you to change her grade to a D so that she can use it as one of the courses she is going to drop under the firstyear grade exclusion rule. What would you do? Hypothetical Score Distribution 400 possible points 372 344 317 297 364 338 316 295 363 337 310 286 360 335 310 285 360 335 309 280 359 329 306 276 357 325 304 275 350 325 298 275 260 258 257 249 248 246 243 242 236 221 220 219 218 210 188 186 X. Class Management - Overview • • • • Some sample cases Rules and procedures Prevention is the best strategy Common problems Case #1 A distraught student tells Professor Johnson that her boyfriend since 8th grade broke up with her two days ago. She has been crying steadily and cannot concentrate on her studies. She begs to postpone taking tomorrow’s exam and for an extension on the written assignment. Professor Johnson grants both, adding, “Don’t tell anyone that I’m letting you do this.” (Perlman, et al, 1999) Case #2 Joshua comes to class each days and sits at the back of the room. He brings a copy of The Battalion with him each day that he reads during most of the class. Case #3 Carrie also comes to class each day. On most days she falls asleep at the beginning of the class and sleeps throughout the class. Note that she is not a snorer. Case #4 Professor Gonzales arrives at his classroom on exam day a few minutes before the exam is scheduled. He notices that fewer than half of his students are there and that someone has written on the board, “Dr. Gonzales’ exam today has been cancelled.” (example from Donald McBurney) Case #5 Carla likes to wear her earbuds to class on days she is taking an exam. She says the music reduces her test anxiety. Case #6 In your syllabus description of the required paper for your class you have indicated that points will be deducted for the use of sexist language. A student informs you that she has no intention of avoiding the use of such language and that she considers your practice nothing more than political correctness. She says that if you penalize her for such language that she will take her case to the University Academic Review Board. Rules and Procedures • Know the university rules • Decide what classroom rules are important to you (reading a newspaper, studying for another class, cell phones) • Communicate those rules on Day 1 orally, and include them in your syllabus • Enforce them • Be clear, fair, and consistent (and keep student embarrassment in public to a minimum) Prevention is best but… No matter how hard you try, you will not anticipate all the problems that will come up in your class. Experience will help. Common Problems: SI • • • • • • • • • Students talking in class (when they shouldn’t) Students sleeping Students challenging your authority Eating or drinking noisily (smelly foods) Cell phones, texting, playing on computers Arriving late, packing up early Cutting class Acting bored Cheating on exams, plagiarism Cheating Is a Biggie • Students seem ever creative in their cheating strategies (foot signals, writing on body parts) • Accusation of cheating can have far-reaching consequences for the student and for you • Know the university rules • It is sometimes difficult to prove (extra proctor) • If problems arise, alert your Dept. Head and seek her/his support • Work hard to prevent it! • If it happens, pursue the charges Other Course Management Issues • • • • • • • • • Distributing exams in large classes Proctoring exams in large classes Meeting with students from large classes Posting exam scores (know the rules) Students’ review of their exams Taking attendance Student questions in large classes Student appeals for exceptions Evaluating excuses Excuses (from Doug Bernstein) • I can’t take the test Friday because my mother is having a vasectomy. • I can’t be at the exam because my cat is having kittens and I’m her coach. • I’m late for the test because I hit a toilet in the middle of the road. • I’m too happy to give my presentation tomorrow. (The instructor noted that this problem was easily fixed.) • I can’t take the exam on Monday because my mom is getting married on Sunday and I’ll be too drunk to drive back to school. • I can’t finish my paper because I just found out that my girlfriend is a nymphomaniac. • Two students sitting next to each other in an exam were asked why they had identical answer sheets even though they had different forms of the exam. Their answer: “We studied together.” XI. Advising, Mentoring • Academic advising • Career advising • Personal advising (counseling?) – Know what is available at your university (handouts) • Research mentoring • Teaching mentoring • Clinical supervision May 17 – Thursday 9:00 – 10:15 Writing Computers in teaching Media 10:35 – 11:50 Large Classes Team Teaching Course Evaluation XII. Writing - Overview • Learning to write – The need to write well – The problem at large universities – The solutions? • Writing to learn – Low stakes writing – High stakes writing – Two-minute papers The Need to Write Well • • • • Most jobs require some writing Good writing is correlated with good thinking Good writing is correlated with good speaking Good writing is about clear communication The Problem of Large Classes • In large classes, students typically don’t write – No papers, no essay exams, no essay questions on exams – The public complains – Jack and Jill can’t write • Solutions – – – – The English Department can’t do it all Writing across the curriculum movement “W” courses Calibrated Peer Review (CPR) is both WTL and LTW Writing to Learn • Mostly short papers • Some are peer examined but not graded • Good way for instructor to get feedback about student understanding • Instructor can grade them or simply score them as “turned in” – “not turned in” • Low stakes writing is often not graded, assignments are short (e.g., journals) • High stakes writing is graded, figures prominently in grade calculation, more involved and longer writing assignments Writing to Learn, Learning to Write See Bibliography on My Website XIII. Computer Technologies -Overview • • • • Classroom Presentations Student Note-taking in Class Communication with Students Course Data Management First Question to Ask How Do I Plan to Use the Technology, and Do I need It? Classroom Presentations • PowerPoint – Are there better systems for creation of presentations? –Adobe Acrobat, Macromedia Flash, SkunkLabs Liquid Media • • • • Use of the Internet (research, a million demos) Graphics programs (SmartDraw) Electronic databases Streaming audio and video Communication with Students • • • • E-mail (distribution list) Bulletin board, listserv, E-learning Web conferencing Website – – – – – – Lecture notes (PowerPoint slides) FAQ bulletin board Links to websites students might need Documents related to the course, previous exams? Advising notes (e.g., TAMU Counseling Center) Course syllabi Course Data Management Systems: Gradebook, WebCT, Blackboard • Grades • Attendance • Research participant hours XIV. Media The computer has eliminated most other forms of media in the classroom. • Media outside the classroom: the television assignment (data collection, writing assignments, observational skills, common experience activities) • Video – brief is better • Audio – provide a transcript XV. Large Classes • • • • • There’s even an acronym – LGI Depersonalization of students Greater course management problems Instructor gets to know mostly the students who do poorly on the exams Research shows that students enjoy these classes more when they are tested at higher cognitive levels Most student questions in class are procedural Large Classes (continued) • Students and professors prefer smaller classes (no achievement differences between small and large but…) • On measures of long-term retention, critical thinking, student motivation, and application of learning, smaller is better • Create small discussion groups staffed by graduate or undergraduate students • Use active learning exercises to involve students and break up the lecture Large Classes (continued) • Some instructors prefer large classes – theatrical types, e.g., James Maas, Henry Pronko • Some students prefer large classes – can be anonymous, likely won’t have to write Large Class: A Model PSYC 107 – 240 Students Meets Mon and Wed 9:10 to 10:00 Instructor and Two Graduate Teaching Assts. Each graduate student has four 50-minute sections of 30 students each (good apprentice program) Instructor meets weekly with the GTAs to plan the small group classes Guiding principle is to take advantage of the small class size – NOTHING should be done there that could be done in the large class XVI. Team Teaching -- Overview Team teaching Co-teaching Collaborative teaching What team teaching usually means What our team teaching is like – problems and solutions What Team Teaching Usually Means • Faculty members from different disciplines • More rarely - faculty members in the same discipline from different areas • Typical model – Shared planning – Shared instruction (both are always present) – Shared assessment Team Teaching in Psychology at Texas A&M • Two graduate students, often first-time teachers, usually in PSYC 107 • Idea is that it amounts to assigning half a course to each graduate student instructor • Sometimes the two instructors offer different expertise (e.g., clinical, cognitive), sometimes not • Too often the instructors get only a few weeks notice of their teaching assignment Successful Team Teaching of the TAMU Variety • Instructors should bring different areas of expertise to the class • Instructors should have good chemistry between them • Instructors should both be present in every class, even though one may have full instructional responsibility • Instructors should have similar teaching and assessment styles • Instructors should alternate, but not usually on an every-other-day basis Potential Problems • Students will like one instructor more than the other (sometimes there is competition for student approval) • Testing styles can be too different • Students are confused about expectations because of two teachers • Instructor absence sends wrong message about importance of the class Preventing Problems Offer rather full disclosure the first day • We are new at this and will be working hard to do a good job as teachers • We know you may have some problems with our different styles but that can be a plus, because it reflects our personalities and our interests • We will collaborate on preparation of all exams so that each exam should be similar in style and level of difficulty • We will be here together each day, even though one of us will be the primary instructor on any given day. We do that because we are committed to this course, not just half of it. • After the first 4 weeks we will ask for anonymous evaluations of how the course is going so that we can make whatever course corrections are necessary. Planning the Team-Taught Course • Agree on your goals for the course, how you will implement them, and how you will assess them • Agree on class management issues • Divide topics according to strengths • Set the schedule so that you change primary instructors every 3 to 4 class meetings New Teachers, in a Team or Not • Show your draft syllabus to an experienced teacher, ideally someone who has taught the course to which you are assigned • When preparing your first exam, show some or all of it to that same individual for her/his opinion • If you have a problem you can’t seem to fix or don’t know how, seek help immediately – don’t let it go on • Be willing to learn from others. There is no shame in seeking help. XVII. Evaluation of Teaching It’s always about getting better! • • • • Feedback from students Feedback from student performance Feedback from faculty peers (peer teams) Feedback from teaching specialists (CTE) Teaching Workshop 2012 Teaching of Psych books bibliography Goals article (2005) Goals questionnaire Lecture chapter (2002) Active learning lecture Active learning chapter (1993) Aggression article (1985) Aggression questionnaire Personality exercise (1983) Answer changing article (1984) Writing exercises in psychology bibliography Teaching large classes bibliography PowerPoints for this workshop