What does my UIM attending expect on the Mini-CEX?

advertisement

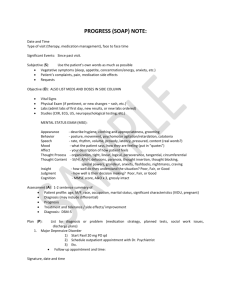

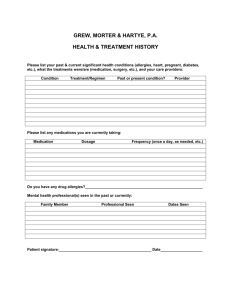

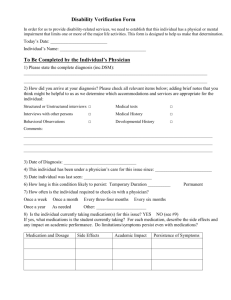

What does my UIM attending expect on the Mini-CEX? Round 1 7/17/13 General Guides The Mini-CEX, or observed history and physical exam, is a board requirement of the ABIM The attending physician must observe you as you do portions of the history and physical. Do not ask the attending to “sign off” because you have presented the history or physical findings Your attending will not make overt corrections to your technique when you are with the patient, but will give you feedback afterward. We do not want to undermine your relationship with the patient Plan the Mini-CEX, tell the attending, then take the attending in the room to watch – no need to do this twice. Use Chief Complaint as your guide. General Guides Barbara Bates remains a great reference All of your histories and physicals will be tailored to the patient’s chronic issues or chief complaints (for the rest of your life!) Get patients into gowns for anything involving a stethoscope. Nothing causes your UIM attending more angst than watching you try to auscultate anything through clothes! You need your H&P skills for outpatient Internal Medicine – this is our main procedure Relative Gain from the History, PE and labs “In 61 patients (76%), the history led to the final diagnosis. The physical examination led to the diagnosis in 10 patients (12%), and the laboratory investigation led to the diagnosis in 9 patients (11%). The internists' confidence in the correct diagnosis increased from 7.1 on a scale of 1 to 10 after the history to 8.2 after the physical examination and 9.3 after the laboratory investigation.” West J Med. 1992 February; 156(2): 163–165 Physical Exam remains important "You know, we often spend so much time with that entity in the computer — I call it the 'iPatient,' like your iPad and your iPhone. And the real patient in the bed is often left wondering, 'Where is everybody? What are they doing?' I sense that we're spending very little time at the bedside.“ Abraham Verghese, MD Stanford – quoted on NPR Mini-CEX UIM 2013 Item Date 1. History of a new complaint 1. Medication history 1. Chronic pain history (psych) Focused physical exam 1. 1. CV exam 1. Lung exam 1. Abdominal exam 1. Musculoskeletal exam 1. Neurological exam 1. Pelvic exam (GYN) 1. Knee exam (Ortho) 1. Shoulder exam (Ortho) 1. Hip exam (Ortho) 1. Teach-back 1. Shared decisionmaking Supervisor History of a new complaint Remember “COLDERR AS” for pain: “O” Onset “L” Location “D” Duration “C” Character/Quality “S” Severity “R” Radiation “E” Exacerbating/”R” Relieving “A” Associated symptoms Medication History Physicians should be doing “Medication Reconciliation” Medication Reconciliation Create the most accurate list possible of all medications a patient is taking Compare that list against the physician’s admission, transfer, and/or discharge orders GOAL: provide correct medications to patient at all transition points (Amy Thompson, PharmD) Drug Name Dosage Frequency Route Medication History Emphasis at Hospital Discharge Comparing what patient is taking at home to the Epic list and hospital discharge list – identifying high risk medications Using outside resources Call pharmacies/family Home Health orders Creating accurate list in Epic Using Teach-Back to clarify patient instructions Chronic Pain History History of the pain including diagnostic studies All medical records obtained including DHEC report Previous treatments and response/adverse effects – focus on function Psychosocial factors and family history – include compensation/legal factors UDS Goals of therapy - functional Assessment of risks for opioid abuse (DIRE) Personal or family history of drug abuse(tobacco use) Psychological factors: personality disorder, affective disorder, etc. Reliability: medication misuse, missed appointments Social support Efficacy: functional Documentation in the Problem List Focused Physical Exam Can you limit the physical to the chief complaint and/or chronic medical conditions? HTN – CV exam, measure BP manually Cardiac history – CV exam, lungs Headache – neuro exam critical Etc. Teach-Back [Elisha Brownfield] stolen from: A program created by the Minnesota Health Literacy Partnership The problem with communication is the illusion that it has occurred. >-- George Bernard Shaw Teach-Back . . . ● Asking patients to repeat in their own words what they need to know or do, in a non-shaming way. ● NOT a test of the patient, but of how well you explained a concept. ● A chance to check for understanding and, if necessary, re-teach the information. Teach-Back . . . Why? Teach-Back is supported by research! ● “Asking that patients recall and restate what they have been told” is one of the 11 top patient safety practices based on the strength of scientific evidence.” AHRQ, 2001 Report, Making Health Care Safer ● “Physicians’ application of interactive communication to assess recall or comprehension was associated with better glycemic control for diabetic patients.” Schillinger, Arch Intern Med/Vo640 l 163, Jan 13, 2003, “Closing the Loop” Teach-Back . . . How? Ask patients to demonstrate understanding “What will you tell your spouse about your condition?” “I want to be sure I explained everything clearly, so can you please explain it back to me so I can be sure I did.” “Show me what you would do.” Chunk and check Summarize and check for understanding throughout, don’t wait until the end. Do NOT ask . . . “Do you understand?” Additional Points. . . ● Slow down. ● Use a caring tone of voice and attitude. ● Use plain language. ● Break it down into short statements. ● Focus on the 2 or 3 most important concepts. Shared decision-making What is shared decision making? Shared decision making is an approach where clinicians and patients make decisions together using the best available evidence. (Elwyn et al, BMJ, 2010 Shared Decision-making for: undergo a screening or diagnostic test undergo a medical or surgical procedure participate in a self-management education program or psychological intervention take medication attempt a lifestyle change. www.kingsfund.org.uk Elements from the Clinician developing empathy and trust negotiated agenda-setting and prioritizing information sharing re-attribution (if appropriate) communicating and managing risk supporting deliberation summarizing and making the decision documenting the decision How do I do that? Negotiated agenda setting/prioritizing ‘What do you want to talk about in our time together today?’ ‘What questions do you have?’ What concerns do you have?’ ‘What is it that I need to know so that I can help you reach the best decision?’ ‘There are other things that I’d like to discuss – is that OK?’ How do I do that? Information sharing ‘What do you understand about your condition?’ ‘What do you understand about what is happening in your body when you get your symptoms?’ ‘What have you been told about your condition?’ ‘What have you been told is happening in your body when you get your symptoms?’ ‘What concerns or worries do you have about your condition?’ How do I do that? Re-attribution ‘Many people who have angina think like that. The evidence is that angina isn’t actually a heart attack. Now I have shared that thought with you, what does that mean for you?’