Prosocial Lecture Slides-2

advertisement

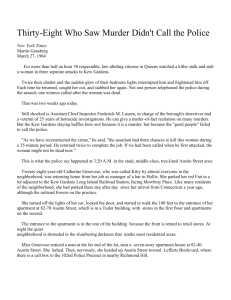

Kitty Genovese Story (From New York Times, March 27th, 1964) 37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector By Martin Gansberg For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens. Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off, Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead. That was two weeks ago today. But Assistant Chief Inspector Frederick M. Lussen, in charge of the borough’s detectives and a veteran of 25 years of homicide investigations, is still shocked. He can give a matter-of-fact recitation of many murders. But the Kew Gardens slaying baffles him — not because it is a murder, but because the ‘good people’ failed to call the police. ‘As we have reconstructed the crime,’ he said, ‘the assailant had three chances to kill this woman during a 35-minute period. He returned twice to complete the job. If we had been called when he first attacked, the woman might not be dead now.’ ‘He Stabbed Me!’ She got as far as a street light in front of a bookstore before the man grabbed her. She screamed. Lights went on in the 10-storey apartment house at 82—67 Austin Street, which faces the bookstore. Windows slid open and voices punctured the early-morning stillness. Miss Genovese screamed: ‘Oh, my God, he stabbed me! Please help me! Please help me!’ From one of the upper windows in the apartment house, a man called down: ‘Let that girl alone!’ The assailant looked up at him, shrugged and walked down Austin Street toward a white sedan parked a short distance away. Miss Genovese struggled to her feet. Lights went out. The killer returned to Miss Genovese, now trying to make her way around the side of the building by the parking lot to get to her apartment. The assailant grabbed her again. ‘I’m dying!’ she shrieked. A City Bus Passed Windows were opened again, and lights went on in many apartments. The assailant got into his car and drove away. Miss Genovese staggered to her feet. A city bus, Q-10, the Lefferts Boulevard line to Kennedy International Airport, passed. It was 3.35 am. The assailant returned. By then, Miss Genovese had crawled to the back of the building where the freshly painted brown doors to the apartment house held out hope of safety. The killer tried the first door; she wasn’t there. At the second door, 82—62 Austin Street, he saw her slumped on the floor at the foot of the stairs. He stabbed her a third time — fatally. It was 3.50 by the time the police received their first call, from a man who was a neighbor of Miss Genovese. In two minutes they were at the scene. The neighbor, a 70-year-old woman and another woman were the only persons on the street. Nobody else came forward. The man explained that he had called the police after much deliberation. He had phoned a friend in Nassau County for advice and then he had crossed the roof of the elderly woman to get her to make the call. ‘I didn’t want to get involved,’ he sheepishly told the police. Suspect is Arrested Six days later, the police arrested Winston Moseley, a 29-year-old businessmachine operator, and charged him with the homicide. Mosely had no previous record. He is married, has two children and owns a home at 133— 19 Sutter Avenue, South Ozone Park, Queens. On Wednesday, a court committed him to Kings County Hospital for psychiatric observation. The police stressed how simple it would have been to get in touch with them. ‘A phone call,’ said one of the detectives, ‘would have done it.’ Today witnesses from the neighborhood, which is made up of one-family homes in the $35,000 to $60,000 range with the exception of the two apartment houses near the railroad station, find it difficult to explain why they didn’t call the police. Lieut. Bernard Jacobs, who handled the investigation by the detectives, said: ‘It is one of the better neighborhoods. There are few reports of crimes. You only get the usual complaints about boys playing or garbage cans being turned over.’ The police said most persons had told them they had been afraid to call, but had given meaningless answers when asked what they had feared. ‘We can understand the reticence of people to become involved in an area of violence,’ Lieutenant Jacobs said, ‘but where they are in their homes, near phones, why should they be afraid to call the police?’ He said that his men were able to piece together what happened — and capture the suspect — because the residents furnished all the information when detectives rang doorbells during the days following the slaying. ‘But why didn’t someone call us that night?’ he asked unbelievingly. Witnesses — some of them unable to believe what they had allowed to happen — told a reporter why. A housewife, knowingly if quite casual, said, ‘We thought it was a lovers’ quarrel’. A husband and wife both said, ‘Frankly, we were afraid’. They seemed aware of the fact that events might have been different. A distraught woman, wiping her hands in her apron, said, ‘I didn’t want my husband to get involved’. One couple, now willing to talk about that night, said they heard the first screams. The husband looked thoughtfully at the bookstore where the killer first grabbed Miss Genovese. ‘We went to the window to see what was happening,’ he said, ‘but the light from our bedroom made it difficult to see the street’. The wife, still apprehensive, added: ‘I put out the light and we were able to see better’. Asked why they hadn’t called the police, she shrugged and replied, ‘I don’t know’. Piliavin, Dovidio, Gaertner, and Clark’s (1981) Model of Factors that lead to Emergency Intervention What factors lead individuals to intervene in emergencies, and what are the causal links among factors? Characteristics of setting, victim and bystander Victim Characteristics Age, gender, race Stigmatizing Conditions, relatedness Features of Situation Number of other people present, Clarity of emergency Mediating processes with bystander Resulting behavior Arousal and its attribution Bystanders Traits Squeamishness, Emotionality, Empathy, Knowledge such as CPR Perceived costs and rewards for helping Intervention or Nonintervention Some Factors Related to Helping Behavior 1) Modeling behavior of others • Car on roadside study 2) Moods [NEGATIVE-STATE RELIEF MODEL] • Broken camera study • Confession study Positive moods = more helping (e.g., finding $, pleasant smells) 3) Ability/Expertise 4) Similarity and Familiarity between helper (s) and victim 5) Perceived Costs (to helper & victim) • Blood versus no blood on victim • Couple arguing versus two strangers arguing 6) Being in a hurry 7) Arousal, attribution and clarity of emergency information Some Factors Related to Helping Behavior (cont.) 8) Gender (and different types of helping) 9) Past personal experience of helping (e.g., reward vs. punishment) 10) Physiological reactions to helping 11) Genetic versus socio-cultural factors (e.g., norm of reciprocity) “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” Positive Smells and Helping No Fragrance Fragrance Males 22.2 45.5 Females 16.7 60.9 The findings were mediated by positive affect * From Baron, R. A. (1997). The sweet smell of … helping: Effects of pleasant ambient fragrance on prosocial behavior in shopping malls. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 498-503. Wrong phone number study Heterosexual making request Homosexual making request 100 90 90 Role of similarity? 80 70 70 60 50 40 35 30 30 20 10 0 Male From Shaw, Borough, & Fink, 1994 Female Number of warnings [Gender bias in helping behavior?] Similarity? Type of crimes: Speeding, DUI, others Driver gender Officer Gender Male Male Female Female Piliavin and Piliavin’s Cost Analysis of Emergency Intervention How do perceived costs for helping and not helping affect our willingness to intervene in an emergency? Piliavin and Piliavin (1972) proposed that a moderately aroused bystander to an emergency assesses the costs of helping and not helping before deciding whether to intervene. The table below predicts what a bystander is most likely to do in an emergency when the costs for helping are low or high and the costs for not helping are low or high. Costs (to helper) for Directly Helping Victim High Low Costs (to victim) if No Direct Help Given Low Direct Intervention Intervention or Nonintervention largely a function of perceived norms in situation High Indirect intervention or Redefinition of the situation, disparagement of victim, etc., which lowers costs for no help, allowing Leaving the scene, ignoring, denial Perceived Costs & Helping Blood on Victim No Blood on Victim Greater levels of helping Strangers Arguing Couples Arguing % helping Time Pressure and Helping 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Ahead of schedule On schedule Behind schedule Non-Arousal Placebo Arousal Placebo Time Elapsed Before Intervention (Seconds) 260 240 220 200 180 160 140 120 100 100 80 60 40 Unambiguous Emergency (with screams) Ambiguous emergency (without screams) Misattribution of arousal and speed of helping in ambiguous or unambiguous emergencies How do attributions of arousal affect our behavior in emergency situations? In Gaertner and Dovidio’s (1997) experiement, subjects sat in a room and heard what sounded like a stack of chairs falling on a woman in the next room. Sometimes the emergency was unambiguous (the woman screamed), and sometimes it was ambiguous (no scream). Subjects had earlier taken a pill (a placebo); some were told that it might increase their heart rate, and some were not. Gaertner and Dovidio measured how quickly subjects responded to the possible emergency in the next room. *** As the previous graph shows, subjects responded more slowly to the ambiguous emergency. Furthermore, subjects exposed to the ambiguous emergency responded even less quickly when they could misattribute their arousal to the pill. Attributions & Helping External attribution (e.g., poor economy is at fault) Positive emotions Helping Helping request (e.g., stranger asking for spare change) Physiological arousal Analysis of the situation Internal attribution (e.g., stranger is lazy) Negative emotions No helping Impact of Past Experience on Helping Thanked for helping Ask for directions Give help “Punished” for helping (“I cannot understand what you’re saying. Never mind, I’ll ask someone else” Less likely to provide assistance in future Personal benefits for helping others 60 “He who helps others helps himself” 50 40 30 20 10 “High” Source: Luks, 1988. Energetic Warm Calm Selfworth Less aches and pains Culture and Helping Country # Helpful Acts Philippines 280 Kenya 156 Mexico 148 Japan 97 U.S. 86 India 60 *Source: Whiting & Whiting, 1975 Does Altruism Exist? “Kindness is it’s own reward.” Egoism: Behaving in one’s own self interest Altruism: Unselfish concern for others • Helping is a behavior • Egoism and altruism are motivational forces How can we know? One assumption: If altruism exists, the level of costs involved should not impact the behavior of those helping out Low Empathy (Dissimilar Victim) % Helping High Empathy (Similar Victim) 90 No difference in helping rates between these 2 conditions 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 Easy Escape [Can leave study] Difficult Escape [Have to stay and watch] Characteristics of People Choosing to Help [Assistance to driver after a traffic accident] • High empathy scores • Strong belief in a just world • Greater levels of social responsibility • Internal locus of control scores • Less egocentric (selfish) Sample Altruism Items • I have given directions to a stranger. • I have given money to a charity. • I have donated blood. • I have delayed an elevator and held the door open for a stranger. • I have allowed someone to go ahead of me in a lineup (at Xerox machine, in the supermarket). • l have pointed out a clerk's error (in a bank, at the supermarket) in undercharging me for an item. • I have helped a classmate who 1 did not know that well with a homework assignment when my knowledge was greater than his or hers. • I have voluntarily looked after a neighbor's pets or children without being paid for it. • I have helped an acquaintance to move households. --- From Rushton, Chrisjohn, & Cynthiafekken Sample Locus of Control Items Do you believe that most problems will solve themselves if you just don't fool with them? Do you feel that you have a lot of choice in deciding who your friends are? Most of the time, do you feel that you can change what might happen tomorrow by what you do today? Do you think that people can get their own way if they just keep trying? Are some people just born lucky? Do you believe that if somebody studies hard enough he or she can pass any subject? Are you often blamed for things that just aren't your fault? Sample Just World items • I am confident that justice always prevails over injustice. • I think basically the world is a just place • I am convinced that, in the long run, people will be compensated for injustices. • I firmly believe that injustices in all areas of life (e.g. professional, family, politics) are the exception rather than the rule. • I believe that, by and large, people get what they deserve • I think that people try to be fair when making important decisions. From: Dalbert, Montada, & Schmitt, 1987) Helping Models Model Problems Solutions Moral Individuals are responsible Individuals are responsible Medical Individuals not responsible Experts responsible Compensatory Individuals not responsible Individuals are responsible Enlightenment Individuals are socialized to be responsible Higher Power Some Issues With Receiving Help • Recipient feeling indebted to the giver (e.g., reciprocity) • Perception of being controlled by the giver • Feeling of inadequacy (lowered self-esteem) “There are different ways of assassinating a man --- by sword, poison, or moral assassination. They are the same in their results except that the last is the more cruel.” Napolean I, Maxims (18041815)