Morality and Consequences

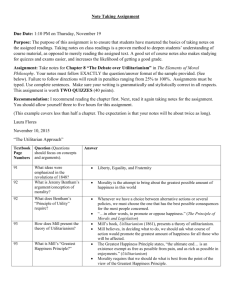

advertisement

Morality and Consequences Agenda • Our Question • Different Kinds of Answer • Consequentialism: The Contingency of Right and Wrong • Varieties of Consequentialism • Attractions of Utilitarianism Some Familiar Moral Facts • Some acts are wrong, others right. • Some acts are morally permissible, others morally impermissible. • Examples: It is morally impermissible for you to lie to your parents about how you spend your book money. It is morally permissible for you to lie to the Nazi who asks you if there are Jews in the house. Our Question • In virtue of what is a given act right or wrong, permissible or impermissible? • For instance, lying to your parents has a different moral status than lying to the Nazi. • That difference justifies taking a different attitude toward them. • What underlies this difference? Agenda • Our Question • Different Kinds of Answer • Consequentialism: The Contingency of Right and Wrong • Varieties of Consequentialism • Attractions of Utilitarianism Different Kinds of Answer I: Actions and Related Matters I want to…, I choose to…, I plan to... Causes Psychological Sources The action itself The consequences of the action The agent • An action is related to many other things. • Different kinds of answers to our question locate the source of right/wrong in different parts of this picture. Different Kinds of Answer II: Consequentialism and Its Rivals • The rightness/wrongness of an act is determined by the nature of… Consequentialism: “its consequences.” Kantianism: “the intentions with which it was done.” Virtue Theory: “what it reveals about the character of the agent.” Different Kinds of Answer III: What’s Distinctive about Consequentialism I want to…, I choose to…, I plan to... Causes Psychological Sources The action itself Consequentialism The agent Kantianism Virtue Theory The consequences of the action Agenda • Our Question • Different Kinds of Answer • Consequentialism: The Contingency of Right and Wrong • Varieties of Consequentialism • Attractions of Utilitarianism Explaining right and wrong • Lying to your parents is impermissible; lying to the Nazi is permissible. • Consequentialist: “What makes the difference is what consequences the lies would have.” • An upshot: Consequentialism implies that the moral status of any action is contingent. Consequentialism: The Contingency of Right and Wrong Causes Causes Pol Pot prevents Actual killing Possible killing • In the actual situation, the action has horrible consequences; • But it’s possible that the horror of those consequences is outweighed. Agenda • Our Question • Different Kinds of Answer • Consequentialism: The Contingency of Right and Wrong • Varieties of Consequentialism • Attractions of Utilitarianism Varieties of Consequentialism I The morally right act is that act (among those available to you) that • Utiliarianism: … maximizes everyone’s utility. • Egoism: … maximizes your own utility. • Satisficing Consequentialism: … meets some threshold for promoting utility. • Rights Consequentialism: … minimizes violations of rights. Varieties of Consequentialism II: What’s Distinctive about Utilitarianism Utilitarianism: The morally right act is that act (among those available to you) that maximizes everyone’s utility. • Everyone’s utility counts. (vs. Egoism) • Maximization required (vs. Satisficing) • Utility is the goal (vs. Rights Conseq’ism) Agenda • Our Question • Different Kinds of Answer • Consequentialism: The Contingency of Right and Wrong • Varieties of Consequentialism • Attractions of Utilitarianism Attractions of Utilitarianism • Consequences are morally relevant. • Examples: How should I break some bad news? Medical triage. • Others’ pleasure/pain is morally relevant. • Examples: Sadistic actions are morally reprehensible. Moral heroes. • Consequences can outweigh other morally relevant factors. • Examples: Breaking a promise to save a life Just wars • Utilitarianism would explain these facts. Mill’s Utilitarianism • John Stuart Mill (1806 1873) • Philosopher, Political Theorist, Reformer. • Mill is one of the most able defenders of Utilitarianism. Agenda • • • • • • • Mill’s Thesis Mill’s Conception of Happiness Objection: The Pig’s Life Bentham’s Defense Mill’s Defense What’s Good? Objections and Replies Mill’s Thesis The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. (p. 487, col. 2) English Translation: “The only fundamental moral requirement is to promote happiness to the best of your ability.” [All other moral requirements follow from that one.] Agenda • • • • • • • Mill’s Thesis Mill’s Conception of Happiness Objection: The Pig’s Life Bentham’s Defense Mill’s Defense What’s Good? Objections and Replies Mill’s Conception of Happiness By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure. (p. 487, col. 2) Mill’s conception of happiness: A is happier than B if and only if A enjoys a higher balance of pleasure over pain. • Note: Pleasure is a mental state. • So, e.g. bodily health is not a direct part of happiness. Agenda • • • • • • • Mill’s Thesis Mill’s Conception of Happiness Objection: The Pig’s Life Bentham’s Defense Mill’s Defense What’s Good? Objections and Replies The Pig’s Life: Who’s Happier? Now, such a theory of life excites in many minds … inveterate dislike. To suppose that life has (as [critics] express it) no higher end than pleasure – no better and nobler object of desire and pursuit – they designate as utterly mean and groveling; as a doctrine worthy only of swine …. (p. 487, col. 2) The Pig’s Life: Who’s Happier? Ouch! Joe: (healthy, except for a backache) Schmoe: (enjoys nothing but heroin) Objection: (1) According to Mill’s conception of happiness, Schmoe is happier than Joe. (2) Schmoe is not happier than Joe. (C) So, Mill’s conception of happiness is false. Agenda • • • • • • • Mill’s Thesis Mill’s Conception of Happiness Objection: The Pig’s Life Bentham’s Defense Mill’s Defense What’s Good? Objections and Replies Bentham’s Defense • One could deny that Joe is happier than Schmoe. • Jeremy Bentham: “Pushpin is as good as poetry.” • Bentham updated: “Heroin is as good as health.” • Perry Farrell seems to be a contemporary adherent. (google“Pigs in Zen lyrics”.) • Call this Bentham’s Defense. Bentham’s Defense • Bentham: Premise (2) is false. False! Objection: (1) According to Mill’s conception of happiness, Schmoe is happier than Joe. (2) Schmoe is not happier than Joe. (C) So, Mill’s conception of happiness is false. Mill Rejects Bentham’s Defense The comparison of the Epicurean life to that of beasts is felt as degrading, precisely because a beast’s pleasures do not satisfy a human being’s conceptions of happiness. Human beings have faculties more elevated that the animal appetites, and when once made conscious of them, do not regard anything as happiness which does not include their gratification. (p. 488, col. 1) Mill Rejects Bentham’s Defense Ouch! Joe Schmoe • Mill: There are more pleasures than food, drink, sex, heroin, etc. • Mill: Joe is happier than Schmoe because he enjoys some of those pleasures. • Mill calls these “higher pleasures”. Agenda • • • • • • • Mill’s Thesis Mill’s Conception of Happiness Objection: The Pig’s Life Bentham’s Defense Mill’s Defense What’s Good? Objections and Replies Mill’s Defense Objection: (1) According to Mill’s conception of happiness, Schmoe is happier than Joe. (2) Schmoe is not happier than Joe. (C) So, Mill’s conception of happiness is false. • Mill: Premise (1) is false. False! • On Mill’s conception of happiness, Schmoe enjoys a full measure of lower pleasures. • But Joe’s existence is overall more pleasant, because Joe enjoys “higher pleasures”. Mill’s Defense: Higher vs. Lower Pleasures Two kinds of pleasures: Higher Pleasures What is it? Examples Pleasures peculiarly suited to our most sophisticated capacities and sensitivities. Poetry, art, music Sociability Positional goods Crosswords, limericks Dice, pushpin, tiddly winks Lower Pleasures Pleasures we share with other sentient animals Food drink and other intoxicants sex exercise warmth Quality vs. Quantity • Bentham: Pleasures differ only in: (i) intensity, (ii) duration, (iii) “propinquity” (proximity in time), and (iv) likelihood. • Mill: They also differ in quality: [U]tilitarian writers in general have placed the superiority of mental over bodily pleasures chiefly in the greater permanence, safety, uncostliness, etc., of the former […] It is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognise the fact, that some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and valuable than others. It would be absurd that while, in estimating all other things, quality is considered as well as quantity, the estimation of pleasures should be supposed to depend on quantity alone. (p. 488, col. 1) Mill: Quality Trumps Quantity [W]e are justified in ascribing to [some] enjoyment a superiority in quality, so far outweighing quantity as to render it, in comparison, of small account. (p. 488, col. 2) • Problem: quality of pleasure is extremely important; but how is it to be determined? Agenda • • • • • • • Mill’s Thesis Mill’s Conception of Happiness Objection: The Pig’s Life Bentham’s Defense Mill’s Defense What’s Good? Objections and Replies Mill’s Epistemology of Value • How do you determine whether one pleasure outweighs another? • Mill’s epistemology of value: Ask the experts: Of two pleasures, if there be one to which all or almost all who have experience of both give a decided preference, irrespective of any feeling of moral obligation to prefer it, that is the more desirable pleasure. (p. 488, col. 1-2) • [Mill notes that the same can be said of whether one “lower” pleasure is more intense than another (p. 489, col. 2)] What the Experts Say 10 out of 10 experts agree! [T]hose who are equally acquainted with, and equally capable of appreciating and enjoying, both, do give a most marked preference to the manner of existence which employs their higher faculties. Few human creatures would consent to be changed into any of the lower animals, for a promise of the fullest allowance of a beast’s pleasures … (p. 488, col. 2) Mill’s Empirical Claim: People who have experienced both higher and lower pleasures much prefer the higher. Is this true? I Couldn’t Resist Quoting This It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question. (p. 489, col. 1) Agenda • • • • • • • Mill’s Thesis Mill’s Conception of Happiness Objection: The Pig’s Life Bentham’s Defense Mill’s Defense What’s Good? Objections and Replies Objections and Replies: Agenda • “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Angels” • “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Supercomputers” Charge: “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Angels” • The idea: no one could possibly be motivated to act as Utilitarianism enjoins. • You love yourself, your parents, your friends, etc. • You do not love me, my parents, my friends, etc. • Utilitarianism requires that you act in a way that equally serves the interests of all: • Bentham: “Everyone is to count for one, and no one for more than one.” Charge: “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Angels” The Objection: (1) Utilitarianism requires impartiality: According to Utilitarianism, we ought to act in a way that promotes everyone’s happiness, regardless of how we feel about them. (2) We can’t be impartial: We cannot act in a way that promotes everyone’s happiness, regardless of how we feel about them. (3) Ought implies can: If we ought to act in a certain way, then we can act in that way (C) So, Utilitarianism is false. Mill’s Response: Actions and Motives • Utilitarianism prescribes actions of a certain sort: utility-maximizing for all humanity. • Utilitarianism does not prescribe a motive for those actions. [The objection] mistake[s] a rule of action with the motive of it. It is the business of ethics to tell us what are our duties […] He who saves a fellow creature from drowning does what is morally right, whether his motive be duty, or the hope of being paid for his trouble. (p. 491, col. 1) Mill’s Response: Actions and Motives dist: Rule of Action What is it? Examples A rule which tells us to act in a certain way. Don’t kill Drive on the right Used for Assessment of the action: “Was it wrong?” Motive of Action The psychological factor which induces us to act in a certain way. The psychological trauma associated with killing Fear of death Assessment of the agent: “Is s/he a bad person?” Mill’s Response: Actions and Motives The Objection: (1) Utilitarianism requires impartiality: According to Utilitarianism, we ought to act in a way that promotes everyone’s happiness, regardless of how we feel about them. (2) We can’t be impartial: We cannot act in a way that promotes everyone’s happiness, regardless of how we feel about them. (3) Ought implies can: If we ought to act in a certain way, then we can act in that way (C) So, Utilitarianism is false. • Premise (2) is false: False! We can perform the right actions; Our motive needn’t be angelic, impartial love of all human beings. Objections and Replies: Agenda • “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Angels” • “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Supercomputers” Charge: “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Supercomputers” • The idea: Utilitarian calculations are extremely difficult. • People don’t have the opportunity to do such calculations when deciding what to do. • So people can’t act as Utilitarianism requires. Charge: “Utilitarianism is Ethics for Supercomputers” The Objection: (1) Utilitarianism requires complex calculations: Determining which action maximizes utility requires calculations of a certain complexity. (2) We can’t do complex calculations: We cannot do calculations of that complexity when deciding what to do. (C) Utilitarianism is impractical: So, we cannot determine which action maximizes utility when deciding what to do. Mill’s Response: Utility and Derivative Principles • Utilitarianism is the fundamental principle of morality: maximize utility. • In daily life, we can apply derivative principles: “Don’t murder” “Don’t steal” … There is no difficulty in proving any ethical standard whatever to work ill, if we suppose universal idiocy to be conjoined with it; but on any hypothesis short of that, mankind must by this time have acquired positive beliefs as to the effects of some actions on their happiness; and the beliefs which have thus come down are the rules of morality for the multitude. (p. 493, col. 2) Mill’s Response: Utility and Derivative Principles The Objection: (1) Utilitarianism requires complex calculations: Determining which action maximizes utility requires calculations of a certain complexity. (2) We can’t do complex calculations: We cannot do very calculations of that complexity when deciding what to do. (C) Utilitarianism is impractical: So, we cannot determine which action maximizes utility when deciding what to do. • The conclusion is true, (but harmless): Harmless We can calculate ahead of time to formulate derivative rules; the rules get applied “in the heat of the moment”. The Place of Common Sense Morality User friendly! Common Sense Morality * Don’t murder! Don’t steal! Be honest! Care for your kids! No Exceptions! Foundation ** * has exceptions ** hard to use Maximize utility! Mill’s Proof On the present occasion, I shall … attempt to contribute something towards the understanding and appreciation of the Utilitarian … theory. It is evident that this cannot be proof in the ordinary and popular meaning of the term. Questions of ultimate ends are not amenable to direct proof. Whatever can be proved to be good must be so by being shown to be a means to something admitted to be good without proof. The medical art is proved to be good by its conducing to health; but how is it possible to prove that health is good. […] Considerations may [nevertheless] be presented capable of determining the intellect either to give or withhold its assent to the doctrine; and this is equivalent to proof. (p. 487, col. 1) • Mill: One can give an argument for the principle of utility, but not a proof. Mill’s Proof: Two Tasks Mill aims to show that maximizing everyone’s happiness is the only good. To show: I. Maximizing everyone’s happiness is good; and II. Nothing else is good. Mill’s Proof: Agenda • Clarifications • “Everyone desires happiness.” • “No one desires anything else.” First Clarification: “Good” ≈ “Desirable” Questions about ends are, in other words, questions about what things are desirable. (p. 499, col. 1) • To show that something is good, it suffices to show that it is desirable. • To show that something is not good, it suffices to show that it is not desirable. Second Clarification: Desirable Means vs. Desirable Ends • Desirable means: things desirable because they are means for acquiring something desirable. • Mill’s example is … … money: There is nothing originally more desirable about money than about any heap of glittering pebbles. Its worth is solely that of the things which it bill buy; the desires for other things than itself, which it is a means of gratifying. (p. 500, col. 2) • Desirable ends: Things desirable for themselves. Mill’s Proof: Two Tasks (Again) I. Maximizing everyone’s happiness is a desirable end. II. Everything else that is desirable is either desirable as a means to that end, or desirable as a part of that end. Mill’s Proof: Agenda • Clarifications • “Everyone desires happiness.” • “No one desires anything else.” Mill’s Argument for I: Everyone desires Happiness I. Maximizing everyone’s happiness is a desirable end. [T]he sole evidence it is possible to produce that anything is desirable, is that people do actually desire it. […] No reason can be given why the general happiness is desirable, except that each person … desires his own happiness. […] We have … all the proof … it is possible to require, that happiness is a good: that each person’s happiness is a good to that person, and the general happiness, therefore, a good to the aggregate of all persons. (p. 499, col. 2) Argument: (1) Empirical Claim: Each person desires her own happiness. (2) ‘Desired’ implies ‘Desirable’: If something is desired, it is desirable. (C1) Each person’s happiness is desirable. (C) The happiness of the aggregate of people is desirable. Objection: Does ‘Desired’ Imply ‘Desirable’? ‘Desired’ implies ‘Desirable’: If something is desired, it is desirable. • There seem to be desires without desirability. • Examples (?): Jocko desires to be the 17th person to reach the South Pole. In a fit of pique, Van Gogh desires to destroy his paintings. Objection: Does ‘Desired’ Imply ‘Desirable’? Argument: (1) Empirical Claim: Each person desires her own happiness. (2) ‘Desired’ implies ‘Desirable’: If something is desired, it is desirable. (C1) Each person’s happiness is desirable. (C) The happiness of the aggregate of people is desirable. • Premise (2) is false: False! People sometimes desire things that are not desirable. Objection: The Fallacy of Composition (C1) Each person’s happiness is desirable. (C) The happiness of the aggregate of people is desirable. • Mill infers a feature of the aggregate whole from that feature’s being universally exemplified by its parts. • This is not generally a valid inference: (TRUE) Each person’s weight < 1000 lbs. (FALSE) The weight of of the aggregate of people is < 1000 lbs. • This mistake is called the fallacy of composition. Objection: The Fallacy of Composition Argument: (1) Empirical Claim: Each person desires her own happiness. (2) ‘Desired’ implies ‘Desirable’: If something is desired, it is desirable. (C1) Each person’s happiness is desirable. • The reasoning from (C1) to (C) is bad. It commits the fallacy of composition • Jargon: the inference is “invalid.” Invalid! (C) The happiness of the aggregate of people is desirable. Mill’s Proof: Agenda • Clarifications • “Everyone desires happiness.” • “No one desires anything else.” Mill’s assertion: No One Desires Anything Else II. Everything else that is desirable is either desirable as a means to happiness, or desirable as a part of happiness. And now to decide whether this is really so; whether mankind do desire nothing for itself, but that which is a pleasure to them or of which the absence is pain; we have evidently arrived at a question of fact and experience …. It can only be determined by practised self-consciousness and self-observation, assisted by the observations of others. I believe that these sources of evidence, impartially consulted, will declare that desiring a thing and finding it pleasant, aversion to it and thinking of it as painful, are phenomena entirely inseparable; or rather two parts of the same phenomenon. [T]o desire anything, except in proportion as the idea of it is pleasant, is a physical and metaphysical impossibility. (p. 501, col. 2) • Ask yourself: “Are desirability and pleasantness are the same thing?” • Mill: “Yes!” Apparent Counter-Examples to Mill’s Assertion Mill’s Assertion: Everything else that is desirable is either desirable as a means to happiness, or desirable as a part of happiness. • Apparent Counter-examples: money virtue art etc. Mill’s Defense: Each of these is desirable originally as a means to happiness Later, it may become desirable as a part of happiness. Desired as means to vs. Desired as part of happiness • Something is desired as a means to happiness if and only if it is desired because its possession will cause happiness (i.e. pleasure). • Something is desired as a part of happiness if and only if its possession will itself be pleasurable. Mill’s Defense in Action • Consider money. • Desired as a means: money is originally desired for what it can buy. • Desire as a part of happiness: we come to desire it for its own sake. [T]he love of money is not only one of the strongest moving forces of human life, but money is, in many cases, desired in and for itself; the desire to possess it is often stronger than the desire to use it, and goes on increasing when all the desires which point to ends beyond it, to be compassed by it, are falling off. It may, then, be said truly, that money is desired not for the sake of an end, but as part of the end. (p. 500, col. 2) • [Marx: We fetishize it.] Mill’s Defense in Action Basic Desires Knowledge: Originally: buys And so … Desired as Means: Basic Desires Knowledge Later: buys And so … Desired as Means “It may, then, be said truly, that money is desired not for the sake of an end, but as part of the end.” (p. 500, col. 2) Mill’s View of Virtue I • Virtues include: courage, wisdom, generosity, honesty, etc. • Why do we originally desire virtue? [Utilitarians] believe … that actions and dispositions are only virtuous because they promote another end than virtue. (p. 500, col. 1) • Mill: Because it leads to (general) happiness. Mill’s View of Virtue II • We (also) fetishize virtue: There was no original desire of [virtue] … save its conduciveness to pleasure, and especially to protection from pain. But through the association thus formed, it may be felt a good in itself, and desired as such with as great intensity as any other good; and with this difference between it and love of money, of power, or of fame, that all of these may, and often do, render the individual noxious to the other members of society to which he belongs, whereas there is nothing which makes him so much a blessing to them as the cultivation of the disinterested love of virtue. (p. 501, col. 1) • In fact, we have a moral duty to fetishize virtue. • [This involves getting yourself to desire something which you do not now desire.] Objection: A Tension in Mill’s Discussion • • • • Claim 1: Happiness is a mental state. Claim 2: We can fetishize. [In so doing we create value.] Given the range of human desires, these two claims seem hard to maintain at the same time. • We desire things (for themselves) that are not mental states. • Examples: Jocko desires to be the 17th person to reach the South Pole. Julius desires posthumous fame. Objection: A Tension in Mill’s Discussion Joe wants his child to be happy and successful. Two cases: Joe gets what he wants Joe Junior Joe mistakenly believes he gets what he wants Joe Junior Objection: A Tension in Mill’s Discussion Joe gets what he wants Joe Joe mistakenly believes he gets what he wants Joe Junior Junior Joe is in the same mental states in both cases. If Joe can fetishize Junior’s success, then Junior’s success is part of Joe’s happiness. If Junior’s success is part of Joe’s happiness, then Joe is less happy in the second case. Objection: A Tension in Mill’s Discussion Claim 1: Happiness is a mental state: Happiness consists in pleasure and the avoidance of pain Claim 2: We can fetishize: by desiring something for itself we can make it a part of our happiness. Argument: (1) If Claim 2 is true, then whatever we desire for its own sake is a part of happiness. (2) We desire things other than pleasure and the absence of pain. (C1) If Claim 2 is true, then happiness includes things other than pleasure and the absence of pain. (C) If Claim 2 is true, then Claim 1 is false. Summary Mill’s argument for the principle of Utility faces serious challenges: i. It appears to commit the fallacy of composition. ii. It relies on the idea that desiring something for itself makes it desirable, which leads two problems: a. Counter-examples (i.e. desires without desirability); and b. Apparent conflict with Mill’s conception of happiness as a mental state. Carritt’s Objections • E.F. Carritt (1876 - 1964) • Moral philosopher at Oxford. • Carritt is a minor figure at best, but … • .. this is the earliest version I can find of the objection that Utilitarianism (properly understood) requires wickedness. The internet has given me no picture. Carritt’s Objections: Agenda • • • • Carritt’s Thesis The Standard Utilitarian Response The Arctic Explorer’s Promise The Utilitarian Sherriff Carritt’s Thesis [U]tilitarianism has forgotten rights; it allows no right to a [hu]man [being] because he is innocent or because he has worked hard or has been promised or injured, or because he stands in any other special relation to us. It thinks only of duties or rather of a single duty, to dump happiness wherever we most conveniently can. (p. 505, col. 1) Carritt’s Thesis: Utilitarianism requires wickedness, in the form of violations of rights. Carritt’s Objection: The General Idea • There are situations in which wickedness maximizes Utility. • Carritt’s example: paying what you’ve promised to someone richer. • Utilitarianism says, “Your promise is irrelevant to the rightness/wrongness of the act.” Carritt’s Objection: The General Idea You’ve promised to pay Scrooge … Gimme my money! But spending the money on a night at the opera has better consequences. Kill the Wabbit! Carritt’s Objections: Agenda • • • • Carritt’s Thesis The Standard Utilitarian Response The Arctic Explorer’s Promise The Utilitarian Sherriff Carritt’s Objection: The Standard Utilitarian Response • Effects on the institution: The argument of the utilitarians to explain this has usually been as follows: It is true that a particular instance of justice may not directly increase the sum of human happiness but quite the contrary, and yet we often approve such an instance. This is because the general practice of such good faith, with the consequent possibility of credit and contract, is supremely conducive to happiness, and therefore so far as any violation of a bargain impairs this confidence, it is, indirectly and in the long run, pernicious. (p. 505, col. 1) • Counting only direct, immediate consequences, repaying the rich does not maximize utility. • But violating a promise undermines the institution of promising. • This counts in favor of keeping the promise. Doubts about the Standard Utilitarian Response • Does a a single instance of promise-breaking threaten the institution of promising? • Suppose you marry. Does the fact that someone you know cheats on his/her spouse make you more likely to cheat? • [In my own case: no.] Carritt Rejects the Standard Utilitarian Response • Carritt’s response: add secrecy [The standard Utilitarian response] breaks down because it only applies where the promise and its performance or neglect would be public and therefore serve as an example to others. (p. 504, col. 2) • Two cases: Arctic explorer’s promise Utilitarian Sherriff Carritt’s Objections: Agenda • • • • Carritt’s Thesis The Standard Utilitarian Response The Arctic Explorer’s Promise The Utilitarian Sherriff The Arctic Explorer’s Promise Suppose the two explorers in the Arctic have only enough food to keep on alive till he can reach the base, and one offers to die if the other will promise to educate his children. No other person can know that such a promise was made, and the breaking or keeping of it cannot influence the future keeping of promises. On the utilitarian theory, then, it’s the duty of the returned traveller to act precisely as he ought to have acted if no bargain had been made: to consider how he can spend his money most expediently for the happiness of mankind, and , if he thinks his own child is a genius, to spend it on him. (p. 504, col. 2) • Carritt’s complaint: according to Utilitarianism, the fact that I have promised does not bear on the rightness/wrongness of breaking that promise. The Arctic Explorer’s Promise Last year A: I promise! <wink, wink> A: Sorry, kid. Now The tuition money B left me is better spent on my little genius. B: Use my money to take care of my kids! B’s child: I think I might like to go to college. The Arctic Explorer’s Promise B’s child: I A: Sorry, kid. think I might like to go to college. Argument: (1) If Utilitarianism is true, then A’s promise does not bear on the rightness or wrongness of acting as he’s promised. (2) A’s promise does bear on the rightness or wrongness of acting as he’s promised. (C) Utilitarianism is false. Carritt’s Objections: Agenda • • • • Carritt’s Thesis The Standard Utilitarian Response The Arctic Explorer’s Promise The Utilitarian Sherriff Carritt’s Utilitarian Sherriff [T]he utilitarian must hold that we are justified in inflicting pain always and only in order to prevent worse pain or bring about greater happiness. This, then, is all we need consider in so-called punishment, which must be purely preventive. But if some kind of very cruel crime becomes common, and none of the criminals can be caught, it might be highly expedient, as an example, to hang an innocent man, if a charge against him could be so framed that he were universally thought guilty; indeed this would only fail to be an ideal instance of utilitarian “punishment” because the victim himself would not have been so likely as a real felon to commit such a crime in the future, in all other respects it would be perfectly deterrent and therefore felicific. (pp. 504-5) • Carritt’s complaint: according to Utilitarianism, the fact that someone is innocent does not bear on the rightness/wrongness of punishing him. Carritt’s Utilitarian Sherriff B: I’m innocent! A: Sure, but your suffering is generally useful to humanity. Sherrif Punishment Requires Guilt: It is morally legitimate to punish B for a crime only if B = the person who committed that crime. Carritt’s Utilitarian Sherriff Sherrif Argument: (1) If Utilitarianism is true, then B’s innocence does not bear on the rightness or wrongness of punishing her. (2) B’s innocence does bear on the rightness or wrongness of punishing her. (C) Utilitarianism is false. Utilitarianism vs. Common Sense Morality • Common sense morality is (partly) backward-looking. • According to common sense morality: The moral status of an act depends in part on what you have promised. The moral status of punishment depends in part on what the punishee has done. • Utilitarianism is exclusively forward-looking. • According to Utilitarianism: the moral status of an act depends only on what will (or would) result from it. • Utilitarianism and common sense are at odds.