Teaching Medical Informatics Skills during a Clinical

advertisement

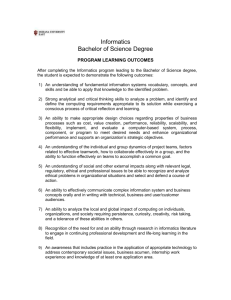

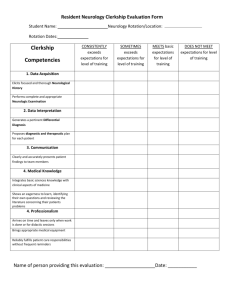

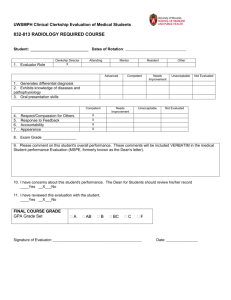

Teaching and Evaluating Informatics Skills During a Clinical Clerkship Shlomi Codish (codish@bgu.ac.il), Akiva Leibowitz, Baruch Weinreb Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel INTRODUCTION AIMS RESULTS DISCUSSION Medical students are expected to demonstrate computer literacy and information fluency by the time they graduate. As residents, they are expected to apply these skills to patient care. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) have both published objectives relating to medical informatics skills (see boxes). 1. To implement an educational program to teach medical informatics skills in a clinical clerkship. 2. To apply the AAMC MSOP recommended strategies as noted on tables 1 and 2. During the academic year 2004, 64 students participated in internal medicine clerkships. They studied in 8 general internal medicine wards, in three hospitals. Before beginning clinical clerkships, student self-assessment of their MEDLINE search skills was low, despite high self-assessment of other computer skills, and a high computer ownership rate. We did not perform an objective assessment of MEDLINE search skills before the clerkship. 3. To develop a multi-dimensional evaluation of the educational program. Baseline information Table 1 A questionnaire distributed at the end of the third year found a low self-assessment of MEDLINE search skills, despite fairly high computer literacy and ownership: Medical students’ information-management skills are formed during their first clinical clerkships; they research patient-centered information using paper-based and electronic resources. This is a uniquely opportune time to teach medical informatics skills. Number of students This poster describes the integration of medical informatics skills in an internal medicine clerkship, applying implementation strategies recommended in the 1998 AAMC Medical School Objectives Program (MSOP) report. METHODS Our intervention consisted of several educational activities: Small group tutorial on the use of PubMed “The medical school must ensure that before graduation a student will have demonstrated, to the satisfaction of the faculty, the ability to retrieve (from electronic databases and other resources), manage, and utilize biomedical information for solving problems and making decisions ...” A two-hour tutorial and an additional two-hour practice session on the use of PubMed. Submission of a patient-related MEDLINE search. Critical evaluation and use of Medical web sites AAMC Medical School Objectives Project, June 1998 Computer-Assisted Learning interventions are often assessed according to: acceptability, usability, knowledge acquisition or behavioral change. Our results indicate success in the first three of these. The two assessment modes showed higher scores for informatics topics than for other topics, and were non-discriminatory. This could be the result of the topic, which is narrower in scope than general internal medicine, or flawed question design. 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 This study has several limitations: Pre-intervention assessment of search skills was not objectively assessed. The scope of skills assessed was limited to search technique rather than finding the correct clinical answer. This was because of the time constraints of OSCE tests. Pre-intervention self-assessment of MEDLINE searching skills. Likert scale (1=very low, 5=very high) A two-hour tutorial on the evaluation of medical information on the Internet (e.g. the HON code and AMA guidelines). Tutorial on the use of medical databases available on the local network (e.g. Micromedex and the Cochrane collaboration) and the computer-assisted learning unit (e.g. DxR and the ACP Clinical Problem Solving Cases). Our intervention related directly to many of the 1998 AAMC MSOP Medical Informatics recommendations. Where possible we applied the “ideal state” recommendation. 1 2 3 4 5 Behavioral change, arguably the most important outcome of such an intervention, was not assessed. Our study shows that an integrated educational intervention to teach medical informatics skills during a clinical clerkship is effective. Medical informatics skill acquisition can be assessed as part of the general clerkship assessment. Acceptability Submission of a written evaluation of a medical web site. Development of a courseware site to accompany the clerkship BACKGROUND Medical students, residents and practicing clinicians have been shown to perform poorly in applying online medical resources to answering clinical questions (see accompanying web site for an annotated bibliography). Various forms of interventions, from short tutorials to workshops and full curricular change, have been used to improve this. A courseware web-site was developed to accompany the clerkship (see screen shot). Students were required to maintain a log of clinical encounters using the site. The web site log was analyzed for usage of material and links accessed. Table 1 Curricular implementation issues. from the AAMC MSOP report Acceptability A questionnaire assessing self-evaluation of specific information fluency skills was administered before the clerkship. An additional questionnaire assessing student evaluation of the intervention was administered at the end of the clerkship. The 1998 AAMC MSOP report includes detailed recommendations for implementation of medical informatics education in medical schools and describes initial and ideal states for educational initiatives (tables 1 and 2). The use of electronic resources for medical research is continuously increasing. There has been a discrepancy between self evaluation of search skills and demonstrated performance. One of the items on the annual AAMC questionnaire asks medical school graduates to rank their agreement with the statement that they “have the skill to carry out reasonably sophisticated searches of medical information databases”. The number of students answering “strongly agree” or “agree” to this question has been steady for the years 2002-4 at over 93%. Studies measuring this skill objectively, consistently demonstrate low success rate in answering clinical questions with the use of medical information databases. Evaluation Table 2 Usability Usability was monitored via the courseware site log. Use of educational resources was logged by the specific applications. Acceptability of the intervention: An questionnaire administered at the end of the course asked students to evaluate all interventions (scores on a 1-5 scale with 1=lowest, 5=highest). The average evaluation of the Medline seminars was 4.6, of the medical web seminars 4.0, of the computer based simulation 4.1, and of the courseware web site 3.9. Students open-ended comments were positive. Usability Usability was assessed by monitoring use of the electronic resources accessed via the courseware site. The courseware web site was accessed, on average, 1.2 times per day by each student during the clerkship. The most commonly used pages on the web site were (in decreasing order): Clinical log (2256 hits), forum (977 hits), clinical seminars (959 hits), recommended web sites (519 hits) and online tutorials (246 hits). Knowledge acquisition Questions about the content of the intervention were added to the final exam. Five percent of the final written exam was dedicated to medical informatics. A hands-on assessment of skills was performed by means of a dedicated OSCE station (see below). This comprised 5.3% of the OSCE score. Behavioral change Behavioral change was not assessed in this study. Web Sites 519 Clinical Log 2256 Clinical Seminars 959 The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) evaluates clinical competence by focusing on outcome via observable behaviors. The OSCE is gaining popularity and is used by the National Board of Medical Examiners as part of the USMLE step 2 test. OSCE have been used to assess clinical skills such as interview, physical examination and test performance and interpretation. In this work we used the OSCE to test proficiency in the use of MEDLINE. Overlaying windows from the internal medicine courseware site. The bottom window shows the “course library” menu, with the options for the PubMed section selected. The top window shows part of a practice exam on PubMed. Tutorials 243 All others 688 At the BGU medical school, the use of MEDLINE is taught in the pre-clinical years, a period during which actual MEDLINE use is limited. During clinical clerkships, students are required to research medical topics several times a day. Forum 977 Use of the accompanying courseware site – number of visits per type of page. OSCE Station number 9 [to follow interview of an adult patient with abdominal pain] CONCLUSIONS 1. What is the main problem of the patient you have just interviewed? 2. What is the corresponding MeSH term for this problem? How many alternative terms does it have? In how many different trees does it appear? Table 2 Instructional implementation issues from the AAMC MSOP report “Residents must be able to investigate and evaluate their patient care practices, …Residents are expected to: …use information technology to manage information, access online medical information; and support their own education.” ACGME Outcome Project, February 1999 Screenshot: courseware site 3. Search for randomized-controlled trials relating to the treatment of pancreatitis with antibiotics. Limit the results to match the patient demographics. Print the search results, including the search strategy. Evaluation criteria This poster, along with an annotated bibliography can be found online at http://medic.bgu.ac.il/homes/AMIA05/ • • • • Correct answers to MeSH questions Use of MeSH terms and subheadings Use of Boolean operators Age and gender limits Knowledge acquisition Projects submitted by students (MEDLINE search and web site evaluation) demonstrated good searching and evaluating skills. Development of information management skills has been established as an objective for both medical students (by the AAMC) and for residents (by the ACGME). The first clinical clerkship is a critical time during which these skills are developed. The five informatics questions on the final exam were non-discriminatory. There was no difference in informatics question scores between the students scoring overall grades in the lowest and highest quartiles. The average score for the informatics questions was 84% while the average score of the entire test was 76%. Teaching informatics themes during a clinical clerkship was well accepted by students and faculty. Following our educational intervention, students achieved a high level of information-seeking skills, demonstrated in both a hands-on test and on a written exam. The OSCE station scores were higher than the average score for other OSCE stations: 88% ± 14.9. The correlation between the OSCE station score and the score of other stations was 0.515 (Pearson’s correlation, p<0.001). Evaluation of informatics skills can be effectively incorporated into existing evaluation methods.