Precis Paragraph Compilation

advertisement

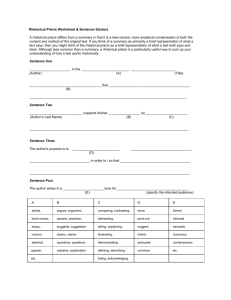

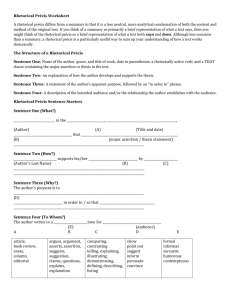

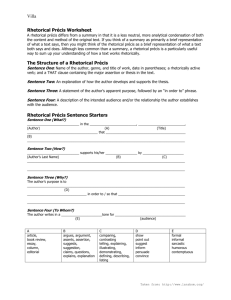

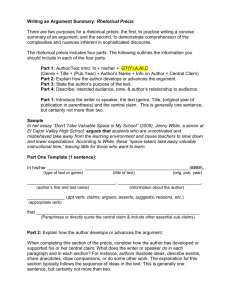

The Rhetorical Précis The formal rhetorical précis is a highly structured four sentence paragraph that records the essential elements (both the content—the what and the delivery—the how) of a unit of spoken or written discourse. A four sentence précis paragraph must include (1) the name of the speaker/writer, the context of the delivery, the major assertion, (2) the mode of development and/or support, (3) the stated and/or apparent purpose, (4) and the relationship established between the speaker/writer and the audience (the last element is intended to identify the tone of the work). Each of the four sentences requires specific information; students are also encouraged to integrate brief quotations to convey the author’s sense of style and tone. Practicing this sort of writing fosters precision in both reading and writing, forcing a writer to employ a variety of sentence structures and to develop a discerning eye for connotative shades of meaning. Format: Sentence 1 The first sentence must include the NAME of the speaker/writer [optional: a phrase describing the author], genre and title of the work, [optional: date and additional publishing information in parenthesis], a rhetorically accurate VERB (such as: “asserts,” “argues,” “suggests,” “implies,” “claims,” etc.), and a THAT clause containing the major assertion (thesis statement) of the work. Example 1: Statesman and philosopher, Thomas Jefferson, in The Declaration of Independence (1776), argues that the God-given rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness entitle the colonists to freedom from the oppressive British government and guarantee them the right to declare independence. NOTE: As long as all of the required information (name, genre, title, publishing information, verb, and a “that” clause) appears in the first sentence, placement of each element doesn’t matter much. Also, if an author has directly stated their claim feel free to quote their thesis exactly as it appears in the original text, but be sure to include page numbers to comply with MLA formatting. If you are writing a précis paragraph on an online publication, page numbers are not necessary. Example 2: In “The Ugly Truth About Beauty” (1998) humorist, Dave Barry argues that “women generally do not think of their looks in the same way that men do” (4). NOTE: It is possible to split the verb and the word “THAT” in the first sentence, but you must be careful not to stick words like “about” and “how” in between the verb and the THAT clause. The following example is done correctly, but separating the verb from the THAT clause is not highly recommended. This type of sentence construction which is meant to paraphrase often slips into summary—a less specific statement of the author’s intentions. Example 3: In “The Ugly Truth About Beauty” (1998), Dave Barry satirizes the unnecessary ways that women obsess about their physical appearance. Utilizing a rhetorically accurate VERB followed by the word “THAT” helps students avoid the use of more general words such as “writes” and “states.” The THAT clause is designed to demand a complete statement: a grammatical subject (the topic of the discourse) and predicate (the claim that is made about that topic). If the THAT clause is not employed students will end up allowing “about” and “how” to slip out in stating the thesis: i.e.., “Sheridan Baker writes about attitudes in writing” or “…states how attitudes affect writing”—neither of which reports what the author claims to be true about attitudes. “About” and “how” are elementary words used in summaries, and précis paragraphs are written to prove that we not only understood the gist of a piece, but that we can pinpoint an author’s thesis, analyze his/her rhetorical strategies, and identify tone and style. 1 Sentence 2: The second sentence is an explanation of HOW the author DEVELOPS and/or SUPPORTS the thesis, usually in chronological order, or organized by identifying the shift in rhetorical mode(s) throughout the work. Example 1 (chronological): He supports his claim by first invoking the fact of our inalienable rights; then, he establishes the circumstances under which a people can throw off an oppressive government; he next proceeds to show that these circumstances have been created by King George III, whose oppressive rule now forces the colonists to the separation. Example 2 (by shifts in rhetoric): Barry illuminates this discrepancy by juxtaposing men’s perceptions of their looks (“average-looking) with women’s (“not good enough”), by contrasting female role models (Barbie, Cindy Crawford) with make role models (He-man), and by comparing men’s interests (the Super Bowl, lawn care) with women’s (manicure). NOTE: Since there are a variety of ways to structure the second sentence, it can get a bit long. This is fine, since it is your main chance to prove to your audience that you really did the reading; better a sentence be long and detailed than short and over-simplified. This is the sentence where sophisticated punctuation marks like the semicolon (;) and the comma (,) are your best friends. Example 3 (chronological with semicolons and commas used to connect clauses): The author develops this assertion first by applying these techniques to two poems; secondly, he provides definitions; lastly, he explains the history of each approach. NOTE: The verbs used in a précis are always in present tense, which helps the author’s writing (and your writing) seem alive. In works of literature, the second sentence may provide a short account of the plot Example 4 (plot-based sentence): Hemingway develops this idea through a sparse narrative about the ‘initiation’ of a young boy who observes in one night both a birth and a death. Sentence 3 The third sentence is a statement of the author’s PURPOSE for writing the text. This sentence must use the infinitive “to” as in the phrase, “IN ORDER TO” to connect the purpose with the action the author wants his audience to take. Remember that one’s purpose is always to put forward a thesis, but there are others as well. The “to” phrase should transcend a phrase such as “Her purpose is to inform”; look beyond such a simplistic response to assess what the author wants the audience to do or to feel as a result of reading the work. Example 1: The purpose of this document is to convince all readers of the necessity to officially declare independence from Great Britain in order to establish a separate independent nation: the United States of America. Example 2: Barry uses exaggerations and stereotypes to achieve his purpose of calling attention to gender differences in order to prevent women from so eagerly accepting society’s expectations of them; to this end, Barry claims that men who want women to “look like Cindy Crawford” are “idiots,” implying that women who adhere to the Crawford standard are fools as well (10). 2 Sentence 4 The fourth sentence in a précis paragraph includes a DESCRIPTION of the intended AUDIENCE and the RELATIONSHIP the author establishes with the audience. Students need to ask how the language of the work excludes certain audiences (non-specialists would not understand the terminology; children would not understand the irony) in order to see that the author did make certain assumptions about the pre-existing knowledge of the audience. The sentence should also report the author’s TONE. Example 1: Jefferson establishes a passionate and challenging tone for a worldwide audience, but particularly the British and King George III. Example 2: Barry ostensibly addresses men in this essay because he opens and closes the essay directly addressing men (as in “If you’re a man…”) and offering to give them advice in a mockingly conspiratorial fashion; however, by using humor to poke fun at both men and women’s perceptions of themselves, Barry makes his essay palatable to women as well, hoping to convince them to stop obsessively “thinking they need to look like Barbie” (8). Put it all together and you sound incredibly sophisticated! Student Sample Bell Hooks, in her essay “Women Who Write Too Much” from Remembered Rapture (1999), suggests that all dissident writers, particularly black female writers, face enormous time pressures; if they are not prodigious, they are never noticed by mainstream publishers. She supports her position first by describing her early writing experiences that taught her to “not be afraid of the writing process”; second, by explaining her motives for writing, including “political activism”; and lastly, by affirming her argument, stressing that people must strategically schedule their writing and “make much of that time.” Her two-pronged purpose is to respond to critics and encourage minority writers to develop their own voice. Although at times her writing seems almost didactic, Hooks ultimately establishes a companionable relationship with her audience of both critics and women who seek the effectiveness of their own writing. To prepare to write a précis paragraph you might want to TAP(S) the passage first. Identify the TOPIC, AUDIENCE, PURPOSE, and SPEAKER of the piece you are meant to write about. This is a good place to start. Then, just identify the remaining information, and then plug it in to the précis formula. A précis is only a précis if you follow the four sentence formula. Sentence 1 AUTHOR/SPEAKER’S NAME: ____________________________________________________________ TITLE OF WORK (often suggests the TOPIC): ________________________________________________ PUBLICATION DATE: ___________________________________________________________________ THESIS: ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ Sentence 2 DEVELOPMENT/SUPPORT: __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ Sentence 3 PURPOSE: _____________________________________________________________________________ Sentence 4 AUDIENCE:_____________________________________________________________________________ 3 Fill-in-the-Blank Précis Paragraph Practice In “_________________________________________________” ( ), ___________________________ title of work date published Author/Speaker’s full name ____________________ that _________________________________________________________________ present tense verb state the thesis _________________________________________________________________________________________. _______________________ __________________________________________________________________ Author/Speaker’s last name use active verbs to tell HOW the thesis is developed or supported _________________________________________________________________________________________ (separate independent clauses with semicolons if you need to) _________________________________________________________________________________________. _______________________ purpose is to _______________________________________________________ His/her _________________________________________________________________________________________ in order to________________________________________________________________________________. _______________________ address an audience of _______________________________________________ Author/Speaker ___________by ____________________________________________________________________________ explain HOW the author develops a relationship or uses a particular tone with his/her audience _________________________________________________________________________________________. As you get better are writing précis paragraphs, you will want to challenge yourself to vary the structure of the four sentences. For example, sometimes you may want to begin with an author’s name instead of the title of the work. Even though the structure of the individual sentences may change, you should never vary the purpose or order of the sentences. If you cannot highlight a verb and the word “that,” the word “purpose,” and the word “audience” in your final précis, you might need to revise or even rewrite your paragraph. Similar to math, writing a précis is a task which requires a language formula that must be strictly followed. Plug in the right information in the right spot, and you are on your way to becoming a more educated and informed communicator. Précis can also be used as part of an introductory paragraph in a literary response and analysis essay. If you can’t think of a way to begin your analysis, write a précis and then develop your own thesis statement to launch into a deeper analysis of text! Learn the formula, practice, and watch your analysis skills soar! 4 Here is a list of verbs you might find helpful. Strive to employ the most connotatively precise words you can. Accentuates Accepts Achieves Adds Adopts Advocates Affects Affirms Alleges Alleviates Allows Alludes Amplifies Analogizes Analyzes Approaches Argues Ascertains Asserts Assesses Assails Assumes Attacks Attempts Attests Attributes Augments Avoids Bases Believes Bolsters Bombards Challenges Champions Changes Characterizes Chooses Chronicles Claims Clarifies Comments Compares Completes Concerns Concludes Condemns Condescends Conducts Conforms Confronts Connotes Considers Constrains Constructs Contends Contests Contradicts Contributes Conveys Convinces Creates Critiques Declares Deduces Defends Defines Defies Delineates Demonstrates Denigrates Denotes Denounces Depicts Describes Details Determines Develops Deviates Differentiates Differs Directs Disappoints Discerns Discovers Discusses Dispels Displays Disputes Disrupts Dissuades Distinguishes Distorts Downplays Dramatizes Elevates Elicits Elucidates Embodies Empathizes Emphasizes Empowers Encounters Enhances Enlightens Enriches Enumerates Envisions Escalates Establishes Evokes Evaluates Excludes Exhibits Expands Experiences Explains Explicates Expresses Exemplifies Extends Extrapolates Fantasizes Focuses Forces Foreshadows Forewarns Fortifies Fosters Functions Generalizes Guides Hints Holds Honors Heightens Highlights Identifies Illuminates Illustrates Imagines Impels Implements Implies Includes Indicates Infers Initiates Inspires Intends Intensifies Interprets Interrupts Introduces Inundates Provides Provokes Purports Juxtaposes Justifies Rationalizes Reasons Recalls Recapitulates Recites Recollects Records Recounts Reflects Refers Refutes Regales Regards Regrets Relates Reinforces Rejects Remarks Represents Repudiates Reveals Reverts Ridicules Lampoons Lists Maintains Magnifies Manages Manipulates Masters Meanders Minimizes Moralizes Motivates Muses Notes Observes Opines Opposes Organizes Outlines Overstates Paints Patronizes Performs Permeates Permits Personifies Persuades Pervades Ponders Portrays Postulates Predicts Prepares Presents Presumes Produces Projects Promotes Proposes 5 Qualifies Questions Satirizes Sees Selects Serves Solidifies Specifies Speculates States Strives Suggests Summarizes Supplies Supports Suppresses Sustains Symbolizes Sympathizes Traces Transcends Transforms Understands Understates Unpacks Uses Vacillates Values Verifies Views Wants Wishes R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R S S S S S S S S S Works Cited Barry, Dave. “The Ugly Truth about Beauty.” Mirror on America: Short Essays and Images from Popular Culture. 2nd ed. Eds. Joan T. Mims and Elizabeth M. Nollen. NY: Bedford, 2003. 109-112. Print. Bean, J.C., Chappell, V.A., & Gillam, A.M. Reading Rhetorically, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Longman. 2011. Print. Koster & Hudson. “Rhetorical Precis.” Rhetorical Review, Vol. 7. No. 1. 2004. Web. 6