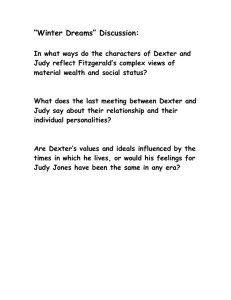

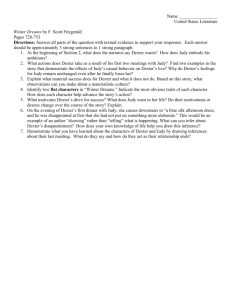

a comparison of the characters Dexter from Scott Fitzgerald's “Winter

advertisement

Genoese 1 Maria Genoese May 10, 2013 Readings in US Literature Inclination to Change It's a fundamental element of fiction that the protagonist undergoes change. For some characters, the change may happen abruptly, and for others, the change may take a lifetime. Some characters will the change to happen, while others are resistant or trapped in their old ways - but even if a conflict of old vs. new occurs, the protagonist will undergo some kind of change over the course of the story, one way or another. In "Winter Dreams" by F. Scott Fitzgerald and "A Rose for Emily" by William Faulkner, both protagonists feel the urge to change how they are recognized by society, but are restricted by their inability to come to terms with who they are. In the cases of Dexter Green and Emily Grierson, the protagonists of the two works, they're unable to become someone new without recognizing who they used to be. In "Winter Dreams," Dexter is eager to become someone new, even at the age of fourteen. Caddying for the upper-crust members of the Sherry Island Golf Club, he spends his teen years experiencing the glamorous lifestyle from the other side of the fence, seeing the rich be rich while being unable to participate himself. In the beginning of the story, we see him quit caddying after his run-in with Judy Jones: "Miss Jones is to have a little caddy, and this one says he can't go." "Mr. McKenna said I was to wait here till you came," said Dexter quickly. "Well, he's here now." Miss Jones smiled cheerfully at the caddy-master. Then she dropped her bag and set off at a haughty mince toward the first tee. "Well?" The caddy-master turned to Dexter. "What you standing there like a dummy for? Go pick up the young lady's clubs." "I don't think I'll go out to-day," said Dexter. "You don't----" "I think I'll quit." (Fitzgerald, pg. 2187) Genoese 2 Despite being recognized as one of the favorite caddies and earning a hefty $30 a month a good amount of pocket money for a young man working part-time - Judy's treatment of Dexter is enough to get him to quit. Although he's worked for wealthy golfers all this time, he isn't treated as lower-class; Mr. Jones, Judy's father, praises Dexter as the best caddy he ever saw, calling him "willing, intelligence, quiet, honest, [and] grateful." (Fitzgerald, pg. 2187) But Judy a girl three years younger than Dexter - holds her class over him, expecting the royal treatment simply because she's rich and Dexter isn't; that disrespect causes Dexter to take what he calls violent, immediate action. Flash forward a couple of years and we're shown Dexter turning down a course at the State university in favor of an older, more esteemed university - one that he'd like to associate his name with, in other words. The narrator says, "Often he reached out for the best without knowing why he wanted it" (Fitzgerald, pg. 2190), an endeavor that guides most, if not all, of the decisions Dexter makes throughout the story, like wanting to be with Judy (being seen with Judy, rather) or to be seen at social gatherings; even as he ages, he doesn't let go of the notion that just being rich isn't as glamorous as being seen being rich, as seen during his relationship with Irene. Their engagement was to be announced in a week now--no one would be surprised at it. And to-night they would sit together on the lounge at the University Club and look on for an hour at the dancers. It gave him a sense of solidity to go with her--she was so sturdily popular, so intensely "great." (Fitzgerald, pg. 2198) As an adult, the Dexter who was comfortable caddying for $30 a month is no more, and instead the story follows a Dexter who chases recognition, never happy with what he has. When he has a well-paying job (Fitzgerald, pg. 2190), he doesn't care how much he's making, just that he can talk it up to Judy. When Judy is seeing other men (Fitzgerald, pg. 2192), he waits patiently for her to circle back to him. When he finally settles down with Irene, a girl less renowned than Miss Judy Jones, he's ready to end his engagement to her if it means being in Judy's still-prestigious company again. Dexter's transformation from a content, but dreamy teenager to a desperate reputationchaser is guided by his previously-mentioned need to reach for the best, even if he doesn't know Genoese 3 why he wants it. What we see through "Winter Dreams" is Dexter trying to change who he is to fit an image of what he thinks wealth is supposed to look like, and in the process he loses who he used to be. But because he can't come to terms with his past - a middle-class man with a foreign mother, a hard-working father, and aspirations for notoriety that he can't entirely figure out - his winter dreams are always going to be out of reach; he'll continue living a shallow, unfulfilling life if it means someone will see him doing it, and in the end, his life becomes stable and mediocre, just like Judy's lifestyle loses its shine. In "A Rose for Emily," Emily also struggles to reconcile her past. Emily is regarded as the last of a dying breed, an aristocratic character surrounded by everyday townsfolk who perpetuate gossip and build up an image of her. Like Judy Jones, the fame surrounding Emily is what constructs her legacy, but also like Judy Jones, the legacy surrounding her ends up being more exciting than the actual person. In the passage below, the narrator, the collective voice of the townspeople, tells the event of four men of the town sneaking out to sprinkle lime in Emily's cellar, as to not accuse her to her face of having a stinky house, and Emily's observation of them afterwards. As they recrossed the lawn, a window that had been dark was lighted and Miss Emily sat in it, the light behind her, and her upright torso motionless as that of an idol. They crept quietly across the lawn and into the shadow of the locusts that lined the street. After a week or two the smell went away. That was when people had begun to feel really sorry for her. (Faulkner, pg. 2217) Emily becomes renowned as a town idol, an entity that can be seen overlooking the town from her window, always separated from the townspeople but never out of sight. This degree of separation is what allows the townspeople to see Emily as different from them; they recognize her as this peculiar, mysterious celebrity, and construct their own reality of Emily Grierson. Even when Emily tries to change her ways, the gossip of the town drives her back into seclusion. When she begins seeing Homer, the townspeople talk about it. "But there were still others, older people, who said that even grief could not cause a real lady to forget noblesse oblige—without calling it noblesse oblige. They just said, “Poor Genoese 4 Emily. Her kinsfolk should come to her.".... And as soon as the old people said, “Poor Emily,” the whispering began. “Do you suppose it’s really so?” (Faulkner, pg. 2220) The townspeople immediately cast their opinion onto Emily's relationship - and because Homer doesn't fit the image of what they think a Grierson's significant other should be, they start exclaiming, "Poor Emily." This, like other accounts of gossip surrounding Miss Emily (her buying the arsenic, or teaching children to paint, or eventually returning to the confines of her giant manor), traps Emily into living her life by the townspeople's standards. Although Emily may have been hesitant to change her ways - like not wanting a sidewalk, or numbers put on her house, or having to pay taxes - she did at least attempt to change how the public saw her; her teaching children to paint in itself was an act of the idol coming down to earth, proving her to be more a person and less a story. However, Emily was trapped by who she used to be, the used-to-be-Emily was the one the townspeople perpetuated. When she died and it came to light that she had killed Homer, the townspeople acted surprised; they whispered about how they knew she was crazy all along - that Emily proved she was exactly the person they made her out to be. Both Dexter and Emily had in a mind a way of how they wanted society to see them, but neither of them were able to let go of who they used to be to achieve it. Dexter repeatedly tried to prove, "I'm not middle-class," in an attempt to exist among high society, while Emily repeatedly tried to prove, "I'm not a lonely old aristocrat." But ultimately, their attempt to prove they were someone else only proved the opposite, as Dexter ended up the mediocre Average Joe he didn't want to be, and Emily never shook her reputation as the crazy old mansion lady. Genoese 5 Works Cited Fitzgerald, F. Scott. "Winter Dreams." The Norton Anthology of American Literature.. Gen. ed. Nina Baym. 8th ed. Vol. A. New York: Norton, 2012. pgs 2186-2200. Print. Faulkner, William. "A Rose for Emily." The Norton Anthology of American Literature.. Gen. ed. Nina Baym. 8th ed. Vol. A. New York: Norton, 2012. pgs 2216-2224. Print.