What is a Policy Memo? - Harris School of Public Policy

advertisement

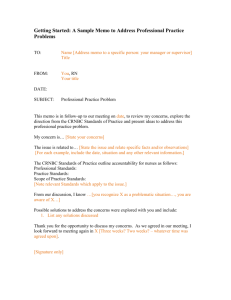

What is the Writing Program? Not a separate class, but instead, the program is folded into the Core classes at Harris Ensures that you gain critical communication skills to showcase your policy analysis expertise Learn how to effectively and persuasively communicate your econometric tests, cost-benefit analyses, and program evaluation findings Why emphasize writing so much? Policy writing is different than academic writing Quantitative skills—the bread and butter of what you will learn this year at Harris—are only useful to the extent that they can support an effective argument There’s no point in publishing the snazziest data points if your key target audience doesn’t understand what you’re talking about Your goal: Learn how to break down complex concepts so that intelligent non-specialists can understand them Don’t leave it to the person who’s reading your work to grapple with what a t-test or a z-score or producer surplus is. Make it easy for them to understand… What can you expect? Many of your Core Classes will have Writing Assignments and/or Policy Memo tasks Some are individual, others will be group-work These assignments will be graded not only on what they say, but how they say it Today we’ll focus on policy memos One of the most commonly used policy-making tools They communicate information to states’ leaders and decision makers that drives choices and negotiations Persuasive, evidence-based, and structured writing of this type represents one of the most powerful ways of influencing the policy-making process Policy memos differ from academic text In the public policy setting, good writing is aimed at immediate effect Likely to be given to someone’s as s/he hurries down the hall or skimmed while making a phone call Take a variety of forms in terms of length, structure and depth of analysis Share a number of common characteristics What is a Policy Memo? Short document used to convey critical information about a specific policy issue Distills a large amount of information or breaks down a complex issue in a concise manner Makes an argument (recommendation) and provides supporting evidence Often evaluates alternative courses of action What is a Policy Memo? Brief: typically 1000 words or less Busy policy-makers will not read long documents and may stop reading short documents that are difficult to understand Direct: addressed to a specific audience Often provided by an advisor to a principal (policymaker or practitioner) but could also be to a colleague Convincing: your ‘bottom line’ should be obvious ‘up front’ Your reader should know the main conclusion of your memo after reading the first paragraph alone 1. Respond to your audience Write for an intelligent non-specialist. You’ll usually be more of an expert on the details than your audience but don’t treat your reader as being stupid Think carefully about the needs and expectations of your audience An elected official will need technical terms defined (don’t use jargon) 2. Organize your memo Introduction including recommendation Background and context Options, supporting arguments/ analysis Conclusion 3. Introduction “Bottom line up front” Open the memo by summarizing the problem/ issue Provide your recommendation The reader should know the main conclusion of your memo after reading the first paragraph alone!! The rest of the memo should be structured around your argument Don’t leave the reader trying to guess your conclusion like a suspense novel! 4. Background and Issues Summarize any historical or technical information that your audience needs for context What is the status quo? Why might it need to be changed? What events have triggered the need for a memo? It may be that no background information is needed at all. 5. Options Identify plausible courses of action, even ones that you might not agree with Point out a few (not a laundry list) pros and cons of each action Identify the risks/ potential opposition from particular courses of action. Anticipate questions 6. Supporting Arguments/ Analysis Provide evidence to support your argument Is there a way to graphically display the information? Help the policy-maker identify who their key supporters and opponents will be, based on your recommendation. Make sure you are clear about the sources of your information (blend the reference into the memo). 7. Conclusion Should be consistent with your recommendation up front No new information should be presented. Keep it short. Wrap up loose ends 8. Style Choose simple words to express your ideas. Avoid jargon—or define your terms clearly. Make your sentences "active voice“ when appropriate. Use each paragraph to develop one idea. Be specific: generic recommendations are not convincing. PROOFREAD CAREFULLY 9. Format Address the memo with a header at the top of the page From: (your name) To: (the person you are addressing) Re: (the scenario you are addressing) Date: (date of submission) Use headings and subheadings Consider using bullets, numbering, and indentations Use bold or italics (but do not overuse) No need for footnotes – if it’s important, highlight a reference in the text Ineffective tables, graphs, and figures Effective tables, graphs, and figures $1,400.00 $1,200.00 $1,000.00 Average Weekly Income $800.00 Men $600.00 Women $400.00 $200.00 $1994 2004 Let’s look at some examples Read this handout http://www.hks.harvard.edu/content/download/66717/1 239678/version/1/file/sample-policy-memo.pdf Discussion Surprises from reading the memo? Things you liked (not content, but style, etc.) How can you write a successful memo? Remember that writing is iterative We learned how to draft in elementary school because it is effective! Write early, put it down, and return to it later with a fresh set of eyes. Have others read your work. Sometimes they will point out tone or grammar that you weren’t aware of. How can you write a successful memo? Avoid sensationalizing the descriptive content of your piece by over-using adjectives Instead, focus on explaining why your evidence proves that the government should adopt your policy. Writing Teaching Assistants Chosen because they are excellent writers and they have also done well in the Core classes Also talented in providing constructive and thoughtful feedback Use them to your advantage (take drafts seriously , attend office hours, send emails) Good policy writing examples Think tanks Brookings Institute Government Entities Government Accountability Office (GAO) Congressional Research Office (these are longer) Other Writing Program Events Monthly newsletter Great tips! Quarterly brown-bag lunches with Harris Alumni working for organizations that prize good policy writing Come network, find out what they think is important about writing, and tips of the trade End of year Writing Prize Earn $$ for your great writing! Writing Resources Our website: http://harris.uchicago.edu/gateways/current- student/harris-school-writing-program Strunk and White’s Elements of Style PlainLanguage.gov: The federal government has been mandated by Presidents Clinton and Obama to use plain language in communication to the public? They’ve built a great site and many of their recommendations are those you're practicing in your policy memos. Explore their guides to word usage, effective headings, and spoken communication. Writing Resources (other schools) The University of California has a fantastic guide to good public policy writing. UMASS: open, online courses on Critical Reading and Writing. ESL-specific exercises available from Purdue University. Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Management. (2010). Memo-Writing Guidelines. Retrieved from http://wagner.nyu.edu/students/services/files/WritingMemos.pdf Writing Resources (University wide) The University-wide Writing Program has resources that may be useful to Harris Students, including: Graduate Writing Consultants: work with writers not just on particular problems in drafts, but also to develop advanced skills for revision. The University’s Little Red Schoolhouse class: a quarter- long, non-credit course Concluding Thoughts Questions? Comments? Don’t hesitate to stop by my office, 181 Or send an email to fvabulas@uchicago.edu