' “She has had the advantage, you know, of practising on me

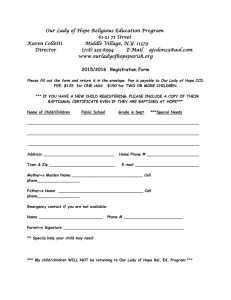

advertisement

Their Fathers’ Libraries: Reading and the Eighteenth-Century Woman Writer Gillian Dow, Chawton House Library and University of Southampton George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss, 1860 ‘She understands what one’s talking about so as never was. And you should hear her read - straight off, as if she knowed it all beforehand. An’ allays at her book! But it’s bad – it’s bad,’ Mr Tulliver added, sadly, checking this blamable exultation, ‘a woman’s no business wi’ being so clever; it’ll turn to trouble, I doubt. But, bless you! […] she’ll read the books and understand ‘em, better nor half the folks as are growed up.’ George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss, 1860 ‘The History of the Devil,’ by Daniel Defoe; not quite the right book for a little girl,’ said Mr Riley. ‘How came it among your books, Tulliver?’ ‘Why, it's one o’ the books I bought at Partridge’s sale. They was all bound alike – it’s a good binding, you see – an’ I thought they’d be all good books. There’s Jeremy Taylor’s Holy Living and Dying among ‘em; I read in it often of a Sunday […] and there’s a lot more of ‘em, sermons mostly, I think; but they’ve all got the same covers, and I thought they were all o’ one sample, as you may say. But it seems one mustn’t judge by th’ outside. This is a puzzlin’ world.’ Self-educated in their Fathers’ Libraries Mary Hays, Female Biography, 1807 On Catharine Macaulay: Her father […] paid no attention to the education of his daughters, who were left […] to the charge of an antiquated, well recommended, but ignorant, governess, ill qualified for the task she undertook […] Having found her way into her father’s well-furnished library, she became her own purveyor, and rioted in intellectual luxury. Every hour in the day, which no longer hung heavy upon her hands, was now occupied and improved. Self-educated in their Fathers’ Libraries Norma Clarke, Queen of the Wits: A Life of Laetitia Pilkington, 2008 As well as giving her free access to his own library, Dr Van Lewen made sure his clever daughter had a plentiful supply of new books – ‘the best, and politest Authors’ – and took pleasure in explaining whatever she could not understand. It appears that this was the extent of her education. No mention is made of schooling, or masters or mistresses. Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote, 1752 From her earliest Youth she had discovered a Fondness for Reading, which extremely delighted the Marquis; he permitted her therefore the Use of his Library, in which, unfortunately for her, were great Store of Romances, and, what was still more unfortunate, not in the original French, but very bad Translations. Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote, 1752 The deceased Marchioness had purchased these Books to soften a Solitude which she found very disgreeable; and, after her Death, the Marquis removed them from her Closet into his Library, where Arabella found them. Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote, 1752 The Impropriety of receiving a Lover of a Father's recommending appeared in its strongest Light. What Lady in Romance ever married the Man that was chose for her? In those Cases the Remonstrances of a Parent are called Persecutions; obstinate Resistance, Constancy and Courage; and an Aptitude to dislike the Person proposed to them, a noble Freedom of Mind which disdains to love or hate by the Caprice of others. Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote, 1752 The Girl is certainly distracted, interrupted the Marquis, excessively enraged at the strange Speech she had uttered: These foolish Books my Nephew talks of have turned her Brain! Where are they? pursued he, going into her Chamber: I'll burn all I can lay my Hands upon. Maria Edgeworth, Mademoiselle Panache, 1801 The carriages drove away, and Mr. Mountague was just mounting his horse, when he saw the book, which had been pulled out of lady Augusta's pocket, and which by mistake was left where it had been thrown upon the grass. What was his astonishment, when, upon opening it, he saw one of the very worst books in the French language, a book which never could have been found in the possession of any woman of delicacy, of decency. Her lover stood for some minutes in silent amazement, disgust, and we may add, terrour. […] ” I can assure you," said her ladyship, ” I don't know what's in this book, I never opened it, I got it this morning at the circulating library at Cheltenham, I put it into my pocket in a hurry — pray what is it?" ” If you have not opened it," said Mr. Mountague, laying his hand upon the book, ”I may hope that you never will, but this is the second volume”. The Modern Minerva; or, the Bat’s Seminary for Young Ladies (1810) ... the lady grew proud; Plain Bat was so horridly vulgar, she vow’d, That the whole clan of vermin and reptiles, by dozens, Might claim her alliance as hundreth cousins; So determin’d the Public in future should see, On her cards of admission, Madame Chauvesouris; As a school must of course rise in merit and fame, If the Governess boast of a Frenchified name. Susan Ferrier, Marriage, 1818 Lady Maclaughlan’s Library ‘All the books that should ever have been published are here. […] Here’s the Bible, great and small, with apocrypha and concordance! Here’s Floyer’s Medicina Gerocomica, or, the Galenic Art of preserving Old Men’s Health; - Love’s Art of Surveying and Measuring Land; - Transactions of the Highland Society; - Glass’ Cookery; - Flavel’s Fountain of Life Opened; - Fencing Familiarized; - Observations on the use of Bath Waters; - Cure for Soul Sores; - De Blondt’s Military Memoirs; MacGhie’s Book-keeping; - Mead on Pestilence; - Astenthology, or the Art of preserving Feeble Life!’ Susan Ferrier, Marriage, 1818 Lady Maclaughlan’s Library Lady Juliana turned over a few pages of her own book, then begged Henry would exchange with her; but both were in so different a style from the French and German school she had been accustomed to, that they were soon relinquished in disappointment and disgust. Susan Ferrier, Marriage, 1818 Lady Juliana on the education of her twin Adelaide, who remains with her in England: As the first step she engaged two governesses, French and Italian; modern treatises on the subject of education were ordered from London, looked at, admired, and arranged on gilded shelves and sofa tables; and could their contents have exhaled with the odours of their Russia leather bindings, Lady Juliana’s dressing-room would have been what Sir Joshua Reynolds says every seminary of learning is “an atmosphere of floating knowledge.’ Susan Ferrier, Marriage, 1818 Lady Julianna on her twin daughter Mary, educated by family in Scotland. Then what can I do with a girl who has been educated in Scotland? She must be vulgar - all Scotch women are so. They have red hands and rough voices; they yawn, and blow their noses, and talk, and laugh loud, and do a thousand shocking things. Then, to hear the Scotch brogue - oh, heavens! I should expire every time she opened her mouth! Anxiety of Female Readership Jeanne Marie le Prince de Beaumont, Magasin des Enfants (1756; contains her version of Beauty and the Beast) Louise d’Epinay, Les Conversations d’Emilie, (1782) Mary Wollstonecraft, The Female Reader: or Miscellaneous Pieces, in Prose and Verse: Selected from the Best Writers, and Disposed under Proper Heads: for the Improvement of Young Women (1789) Catharine Macaulay, Letters on Education (1790) Clara Reeve, Plans of Education with Remarks on the System of Other Writers (1792) Stéphanie-Félicité de Genlis (1746-1830), portraits in collection at Chawton House Library Adèle et Théodore and Adelaide and Theodore Twenty nine editions of French text between 1782 and 1810. English translation 1783; revised edition of the translation published in 1784, reprinted in 1788 and 1796. Spanish, Italian, Dutch, Polish and Russian translations. Madame de Genlis, Adelaide and Theodore ‘Course of Reading pursued by Adelaide, from the Age of six Years, to Twenty-two’ At fourteen she read Tremblay’s Instructions from a Father to his Children; a good book, which contains a course of instruction well written upon all subjects; The History of France, by Velly, &c,; Le Theatre de Boissy; le Theatre de Marivaux, le Spectacle de la Nature, by Mons. Pluche; Histoire des Insectes, in two vols. and Lady M. W. Montague’s [sic] Letters. Adelaide began at this time to read Italian, which she already spoke very well, and set out with the translation of the Peruvian Letters, and les Comedies de Goldoni. […she] also took extracts of what she read. Comments by a British reader, Chawton House Library copy of Adelaide and Theodore Adelaide and Theodore serialised in The Lady’s Magazine May 1785 to April 1789 Woodstock Society 1784, copy of Adelaide and Theodore now in the Bodleian Library Vet A5 e. 5396 Jane Austen’s Emma: The Birth of Miss Weston Mrs. Weston’s friends were all made happy by her safety; and if the satisfaction of her well-doing could be increased to Emma, it was by knowing her to be the mother of a little girl […] no one could doubt that a daughter would be most to her; and it would be quite a pity that any one who so well knew how to teach, should not have their powers in exercise again. ‘She has had the advantage, you know, of practising on me,’ she continued– ‘like La Baronne d’Almane on La Comtesse d’Ostalis, in Madame de Genlis’ Adelaide and Theodore, and we shall now see her own little Adelaide educated on a more perfect plan.’ Jane Austen’s Emma 1815: Mr Knightley on Emma’s reading Emma has been meaning to read more ever since she was twelve years old. I have seen a great many lists of her drawing-up at various times of books that she meant to read regularly through--and very good lists they were--very well chosen, and very neatly arranged--sometimes alphabetically, and sometimes by some other rule. The list she drew up when only fourteen--I remember thinking it did her judgment so much credit, that I preserved it some time; and I dare say she may have made out a very good list now. But I have done with expecting any course of steady reading from Emma. Madame de Genlis, Adelaide and Theodore ‘Course of Reading pursued by Adelaide, from the Age of six Years, to Twenty-two’ At fourteen she read Tremblay’s Instructions from a Father to his Children; a good book, which contains a course of instruction well written upon all subjects; The History of France, by Velly, &c,; Le Theatre de Boissy; le Theatre de Marivaux, le Spectacle de la Nature, by Mons. Pluche; Histoire des Insectes, in two vols. and Lady M. W. Montague’s [sic] Letters. Adelaide began at this time to read Italian, which she already spoke very well, and set out with the translation of the Peruvian Letters, and les Comedies de Goldoni. […she] also took extracts of what she read. Madame de Genlis, Memoirs, 1825 My father had the utmost affection for me; but he did not interfere with my education in any point but one: he wished to make me a woman of firm mind, and I was born with numberless little antipathies: I had a horror of all insects, particularly of spiders and frogs […] He would frequently oblige me to catch spiders with my fingers and to hold toads in my hands. In other respects, Mademoiselle de Mars alone had the direction of my studies; she made me repeat my catechism, and gave me daily a lesson of singing, and two on the harpsichord […] At the request of Mademoiselle de Mars, my father gave us, out of his library, the Clelia of Mademoiselle de Scudery, and the Theatre of Mademoiselle Barbier: these two books were our delight for a long time; and from thence, at eight years old, I began to compose romances and comedies, which I dictated to Mademoiselle de Mars, for I did not yet know how to form a single letter. George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss, 1860 ‘I don’t think I am well, father,’ said Tom; ‘I wish you’d ask Mr. Stelling not to let me do Euclid; it brings on the toothache, I think.’ […] ‘Euclid, my lad,--why, what’s that?’ said Mr. Tulliver. ‘Oh, I don’t know; it’s definitions, and axioms, and triangles, and things. It’s a book I’ve got to learn in—there’s no sense in it.’ ‘Go, go!’ said Mr. Tulliver, reprovingly; ‘you mustn’t say so. You must learn what your master tells you. He knows what it’s right for you to learn.’ George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss, ‘Take back your Corinne’ said Maggie, drawing a book from under her shawl. ‘You were right in telling me she would do me no good; but you were wrong in thinking I should wish to be like her. […] As soon as I came to the blond-haired young lady reading in the park, I shut it up, and determined to read no further. I foresaw that that light-complexioned girl would win away all the love from Corinne and make her miserable. […] If you could give me some story, now, where the dark woman triumphs, it would restore the balance. I want to avenge Rebecca and Flora MacIvor and Minna, and all the rest of the dark unhappy ones.’