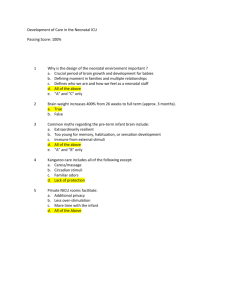

Neonatal Seizures

advertisement

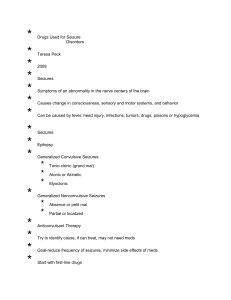

NEONATAL SEIZURES Maria Theresa M. Villanos, MD PL-2 Definition A stereotypic, paroxysmal spell of altered neurologic function (behavior, motor,and/or autonomic function) Definition Neonatal period limited to : - first 28 days for term infants - 44 weeks gestational age for pre-term Frequency In US – incidence has not been established clearly Estimated frequency of 80-120 per 100,000 neonates/year 1-5:1000 live births Frequency 0.5 % incidence -National Collaborative Perinatal Project( population-based study on 54,000 FT and PT infants) 0.23% incidence- Scher, et al (population of 41,00 infants) Incidence of seizures higher in the neonatal period than in any other age group Why do neonatal seizures have such unusual presentations? Immature CNS cannot sustain a synchronized, well orchestrated generalized seizure Perinatal Anatomical and Physiological Features of Importance in Determining Neonatal Seizure Phenomena ANATOMICAL Neurite outgrowth—dendritic and axonal ramifications—in process Synaptogenesis not complete Deficient myelination in cortical efferent systems Volpe JJ.Neonatal Seizures :Neurology of the Newborn.4th ed. Perinatal Anatomical and Physiological Features of Importance in Determining Neonatal Seizure Phenomena PHYSIOLOGICAL In limbic and neocortical regions—excitatory synapses develop before inhibitory synapses ( N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activity, gamma-aminobutyric acid excitatory) Immature hippocampal and cortical neurons more susceptible to seizure activity than mature neurons Deficient development of substantia nigra system for inhibition of seizures Impaired propagation of electrical seizures, and synchronous discharges recorded from surface electroencephalogram may not correlate with behavioral seizure phenomena ______________________________________________________________________ Volpe JJ.Neonatal Seizures.In:Neurology of the Newborn.4th ed. Probable Mechanisms of Some Neonatal Seizures PROBABLE MECHANISM Failure of Na + -K + pump secondary to adenosine triphosphate Excess of excitatory neurotransmitter (eg.glutamic acid—excessive excitation) DISORDER Hypoxemia, ischemia, and hypoglycemia Hypoxemia, ischemia and hypoglycemia Pyridoxine dependency Deficit of inhibitory neurotransmitter (i.e., relative excess of excitatory neurotransmitter) Membrane alteration— Na + Hypocalcemia and Permeability hypomagnesemia _________________________________________________________________ Volpe JJ.Neonatal Seizures:Neurology of the Newborn.4th ed. Classification of Neonatal Seizures Clinical Electroencephalographic Classification I. Clinical Seizure Subtle Tonic Clonic Myoclonic Classification II. Electroencephalographic seizure Epileptic Non-epileptic Clinical Classification 1. Subtle More in preterm than in term Eye deviation (term) Blinking, fixed stare (preterm) Repetitive mouth and tongue movements Apnea Pedaling and tonic posturing of limbs Clinical Classification 2. Tonic Primarily in Preterm May be focal or generalized Sustained extension of the upper and lower limbs (mimics decerebrate posturing) Sustained flexion of upper with extension of lower limbs (mimics decorticate posturing) Signals severe ICH in preterm infants Clinical Classification 3. Clonic Primarily in term Focal or multifocal Clonic limb movements(synchronous or asynchronous, localized or often with no anatomic order of progression) Consciousness may be preserved Signals focal cerebral injury Clinical Classification 4. Myoclonic Rare Focal, multifocal or generalized Lightning-like jerks of extremities (upper > lower) Electroencephalographic seizure I. Epileptic Consistently associated with electro-cortical seizure activity on the EEG Cannot be provoked by tactile stimulation Cannot be suppressed by restraint of involved limb or repositioning of the infant Related to hyper synchronous discharges of a critical mass of neuron Electroencephalographic seizures II. Non-epileptic No electro-cortical signature Provoked by stimulation Suppressed by restraint or repositioning Brainstem release phenomena (reflex) Classification of Neonatal Seizures ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHIC SEIZURE CLINICAL SEIZURE COMMON UNCOMMON Subtle +* Clonic Focal + Multifocal + Tonic Focal + Generalized + Myoclonic Focal, multifocal + Generalized + --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------*Only specific varieties of subtle seizures are commonly associate with simultaneous Electroencephalographic seizure activity. Volpe JJ.Neonatal Seizures:Neurology of the Newborn.4th ed. Does absence of EEG seizure activity indicate that a clinical seizure is non- epileptic? Certain clinical seizures in the human newborn originate from electrical seizures in deep cerebral structures (limbic regions), or in diencephalic, or brain stem structures and thereby are either not detected by surfacerecorded EEG or inconsistently propagated to the surface Surface EEG-Silent Seizure Can “ surface EEG-silent ” seizure in the newborn result to brain injury? Can this be eliminated by conventional anticonvulsant therapy? Further investigation needed Jitteriness Versus Seizure CLINICAL FEATURE Abnormality of gaze or eye movement Movements exquisitely stimulus sensitive Predominant movement Movements cease with passive flexion Autonomic changes JITTERINESS SEIZURE O + + O Tremor Clonic jerking + O O + ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Normal Neonatal Motor Activity Commonly Mistaken for Seizure Activity AWAKE OR DROWSY Roving, sometimes dysconjugate eye movements, with occasional nonsustained nystagmoid jerks at the extremes of horizontal movement (contrast with fixed, tonic horizontal deviation of eyes with or without jerking— characteristic of subtle seizure Sucking, puckering movements not accompanied by ocular fixation or deviation SLEEP Fragmentary myoclonic jerks—may be multiple Isolated, generalized myoclonic jerk as infant wakes from sleep Volpe JJ.Neonatal Seizures:Neurology of the Newborn.4th ed. Etiology It is critical to recognize neonatal seizures, to determine their etiology, and to treat them for three major reasons: 1. Seizures are usually related to significant illness, sometimes requiring specific therapy Etiology 2.Neonatal seizures may interfere with important supportive measures, such as alimentation and assisted respirations for associated disorders. 3.Experimental data give some reason for concern that under certain circumstances the seizure per se may be a cause of brain injury. Etiology Clinical history provides important clue Family history may suggest genetic syndrome Many of these syndromes are benign In the absence of other etiologies, family history of seizures may suggest good prognosis Etiology Pregnancy history is important Search for history that supports TORCH infections History of fetal distress, preeclampsia or maternal infections Etiology Delivery history Type of delivery and antecedent events Apgar scores offer some guidance Low Apgar score without the need for resuscitation and subsequent neonatal intensive care is unlikely to be associated with neonatal seizures Etiology Postnatal history Neonatal seizures in infants without uneventful antenatal history and delivery may result from postnatal cause Tremulousness may be secondary to drug withdrawal or hypocalcemia Temperature and blood pressure instability may suggest infection Comparison of prominent etiologic diagnoses of seizures in the newborn period. (Data modified from Mizrahi and Kellaway, 1987; Rose and Lombroso, 1970) Malformation Hypoglycemia Hypocalcemia Meningitis Stroke 1970 1987 Trauma Hemorrhage Hypoxia-ischemia 0 10 20 30 40 50 Incidence (%) Fanaroff A, Martin R.Neonatal seizures. In:Neonatal and Perinatal Medicine, Diseases of the Fetus and Infant,6th ed Major Etiologies of Neonatal Seizures in Relation to Time of Seizure Onset and Relative Frequency Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy Intracranial hemorrhage‡ Intracranial infection Developmental defects Hypoglycemia Hypocalcaemia Other metabolic Epileptic syndromes TIME OF ONSET* 0-3 DAYS >3DAYS + + + + + + + + + + + + + + RELATIVE FREQUENCY† PREMATURE FULL TERM +++ +++ ++ + ++ ++ ++ ++ + + + + + Inborn Errors of Metabolism Associated With Neonatal Seizures Conditions That Have a Specific Treatment Pyridoxine (B6) dependency Folinic acid-responsive seizures Glucose transporter defect Creatine deficiency Other Conditions Nonketotic hyperglycinemia Sulfite oxidase deficiency Molybdenum cofactor deficiency (combined deficiency) Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein disorder Lactic acid disorders Mitochondrial disorders Maple syrup urine disease Isovaleric acidemia (sweaty feet, cheesy odor) Inborn Errors of Metabolism Associated With Neonatal Seizures Other conditions Isovaleric acidemia (sweaty feet, cheesy odor) 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carbosylase deficiency Propionic acidemia Mevalonic aciduria Urea cycle defects Hyperornithemia-Hyperammonemia-Homocitrullinuria (HHH) syndrome Neonatal glutaric aciduria type ll Biotin deficiencies, holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency Fructose 1,6-diphosphatase deficiency Hereditary Fructose intolerance Menkes disease (trichopoliodystrophy Peroxisomal disorders NeoReviews vol.5 no.6 June 2004 Laboratory Studies to Evaluate Neonatal Seizures Indicated Complete blood count, differential, platelet count; urinalysis Blood glucose (Dextrostix), BUN, Ca, P, Mg, electrolytes Blood oxygen and acid-base analysis Blood, CSF and other bacterial cultures CSF analysis EEG Laboratory Studies to Evaluate Neonatal Seizures Clinical Suspicion of Specific Disease Serum immunoglobulins, TORCH antibody titers, and viral cultures Blood and urine metabolic studies (bilirubin,ammonia, lactate, FECl³, reducing substance.) Blood and urine toxic screen Blood and urine amino and organic acid screen CT or ultrasound scan Metabolic Evaluation for Refractory Neonatal Seizures Consider individually by case specifics Serum Glucose Electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, carbon dioxide), blood urea nitrogen, chromium, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium Uric acid Creative kinase Serum ammonia Lactic and pyruvic acids Biotinidase Amino acids Serum carnitine, acylcarnitines Serum transferrin Copper and ceruloplasmin Cholesterol Fatty acids (short-chain, medium-chain, long-chain) Pipecolic acid NeoReviews vol.5 no.6 June 2004 Metabolic Evaluation for Refractory Neonatal Seizures Urine Organic acids Acylglycines Uric acid Sulfites Xanthine, hypoxanthine Guanidinoacetate Pipecolic acid Cerebrospinal Fluid Cell count, glucose,protein Lactic and pyruvic acids Amino acids Organic acids Neurotransmitters Other Studies Skin biopsy Muscle biopsy Magnetic resonance imaging with magnetic resonance spectroscopy (especially for creatine) NeoReviews vol.5 no.6 June 2004 Treatment Identify the underlying cause: hypoglycemia - D10 solution hypocalcemia - Calcium gluconate hypomagnesemia- Magnesium sulfate pyridoxine deficiency- Pyridoxine meningitis- initiation of antibiotics Treatment To minimize brain damage Some controversy when to start anticonvulsants If seizure is prolonged (longer than 3 minutes), frequent or associated with cardiorespiratory disturbance Drug Therapy For Neonatal Seizures Standard Therapy AED Initial Dose Maintenance Dose Phenobarbital 20mg/kg 3 to 4 mg/kg per day Phenytoin 20 mg/kg 3 to 4 mg/kg per day Fosphenytoin 20 mg/kg phenytoin 3 to 4 mg/kg per day equivalents Lorazepam² 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg Every 8 to 12 hours Diazepam²´ 0.25 mg/kg Every 6 to 8 hours AED= andtiepileptic drug; lV= intravenous; lM= intramuscular; PO= oral ªOral phenytoin is not well absorbed. ²Benzodiazepines typically not used for maintenance therapy. ³Lorazepam preferred over diazepam. Route lV, lM, PO lV, POª lV, lM lV lV Acute therapy of neonatal seizures If with hypoglycemia- Glucose 10%: 2ml/k IV If no hypoglycemia- Phenobarbital:20mg/k IV loading dose If necessary : additional phenobarbital: 5 mg/kg IV to a max of 20 mg/kg (consider omission of this additional Phenobarbital if with baby is asphyxiated) Phenytoin: 20 mg/kg, IV (1 mg/kg/min) Lorazepam:0.05-0.10 mg/kg, IV Pharmacological properties of Phenobarbital Enters the CSF/brain rapidly with high efficiency The blood level is largely predictable from the dose administered It can be given IM or IV(more preferred) Maintenance therapy accomplished easily with oral therapy Protein binding lower in newborn—free levels of drug are higher Entrance to the brain increased by local acidosis associated with seizures Alternative Antiepileptic Drugs (AED) for Neonatal Seizures Intravenous AEDs High-dose phenobarbital: >30 mg/kg Pentobarbital: 10 mg/kg, then 1 mg/kg per hour Thiopental: 10 mg/kg, then 2 to 4 mg/kg per hour Midazolam: 0.2 mg/kg, then 0.1 to 0.4 mg/kg per hour Clonazepam: 0.1 mg/kg Lidocaine: 2 mg/kg, then 6 mg/kg per hour Valproic acid: 10 to 25 mg/kg, then 20 mg/kg per day in 3 doses Paraldehyde: 200 mg/kg, then 16 mg/kg per hour Chlormethiazole: Initial infusion rate of 0.08 mg/kg per minute Dexamethasone: 0.6 to 2.8 mg/kg Pyridoxine (B6): 50 to 100 mg, then 100 mg every 10 minutes (up to 500mg) Alternative AEDs for Neonatal Seizures Oral AEDs Primidone: 15 to 25 mg/kg per day in 3 doses Clonazepam: 0.1 mg/kg in 2 to 3 doses Carbamazepine: 10 mg/kg, then 15 to 20 mg/kg per day in 2 doses Oxcarbamazepine: no data on neonates, young infants Valproic acid: 10 to 25 mg/kg, then 20 mg/kg per day in 3 doses Vigabatrin: 50 mg/kg per day in 2 doses, up to 200 mg/kg per day Lamotrigine: 12.5 mg in 2 doses Topiramate: 3 mg/kg per day Zonisamide: 2.5 mg/kg per day Levetiracetam: 10 mg/kg per day in 2 doses Folinic acid: 2.5 mg BID, up to 4 mg/kg per day NeoReviews vol.5 no.6 June 2004 Determinants of Duration of anticonvulsant therapy for neonatal seizures Neonatal neurological examination Cause of neonatal seizure Electroencephalogram Duration of anticonvulsant therapyGuidelines Neonatal period If neonatal neurological examination becomes normal discontinue therapy If neonatal neurological examination is persistently abnormal,consider etiology and obtain EEG In most such cases- Continue phenobarbital - Discontinue phenytoin - Reevaluate in 1 month Duration of anticonvulsant therapyGuidelines One month after discharge If neurological examination has become normal, discontinue phenobarbital If neurological examination is persistently abnormal,obtain EEG If no seizure activity on EEG, discontinue phenobarbital Prognosis Two most useful approaches in utilizing outcome EEG Recognition of the underlying neurological disease Prognosis of Neonatal seizures in relation to EEG EEG BACKGROUND Normal Severe abnormalities† Moderate abnormalities‡ NEUROLOGICAL SEQUELAE(%) 10 90 ~50 Based primarily on data reported by Rowe JC, Holmes GL, Hafford J, et al: Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 60:183-196, 1985; Lombroso CT: In Wasterlain CG, Treeman DM, Porter R, editors: Advances in neurology, New York, 1983, Raven Press; and includes both full-term and premature infants. †Burst-suppression pattern, marked voltage suppression, and electrocerebral Silence. ‡Voltage asymmetries and “immaturity.” Causes of Neonatal Seizures and Outcomes Cause Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy Intraventricular hemorrhage Subarachnoid hemorrhage Hypocalcemia Early-onset Later-onset Hypoglycemia Bacterial meningitis Developmental malformations Benign familial neonatal convulsions Fifth-day fits Percent of Patients Who Have Normal Development 50 10 90 50 100 50 50 0 ~100 ~100 Complications Cerebral palsy Hydrocephalus Epilepsy Spasticity Feeding difficulties Consultations Neurology consult needed for - evaluation of seizures - evaluation of EEG and video EEG monitoring - management of anticonvulsant medications Further Outpatient Care Neurology outpatient evaluation Developmental evaluation for early identification of physical or cognitive deficits Orthopedic evaluations if with joint deformities Consider physical medicine/physical therapy referral if indicated References 1.Volpe JJ.Neonatal seizures. In:Neurology of the newborn.4th ed.Philadelphia,Pa:WB Saunders's Co;2001:178-214 2.Hahn J,Olson D.Etiology of neonatal seizures.NeoReviews.2004;5:327-335 3.Riviello,J.Drug therapy for neonatal seizures:Part I.NeoReviews.2004;5:215-220 4.Riviello,J.Drug therapy for neonatal seizures:Part II.NeoReviews.2004;5:262-268 5.Fanaroff A,Martin R,Neonatal seizures.In:Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine-Diseases of the fetus and infant.6th ed.St.Louis,MO:Mosby-Yearbook Inc.1997:899-911 6.Sheth R, Neonatal seizures;Emedicine.com Thank You