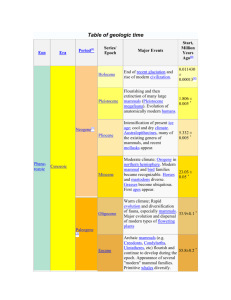

The Brachiopoda and Bryozoa

advertisement

The Bryozoa & The Brachiopoda Paleontology Laboratory III The Bryozoa • The Bryozoa (moss animals) are a geologically important group of small animals. • Some superficially resemble corals. • All bryozoans are colonial and most are marine. • Bryozoans are most abundant in temperatetropical waters that are not too turbid. • They require a hard or firm substrate to attach or encrust, and clear agitated water from which they obtain their suspended food. Bryozoa • There are about 5000 living species, with several times that number of fossil species. • Bryozoan colonies range from millimeters to meters in size, but the individuals that make up the colonies are rarely larger than a millimeter. • Colonies may be mistaken for hydroids, corals, or even seaweeds. Bryozoa • Bryozoans are considered nuisances species by some • Over 125 species are known to grow on the bottoms of ships, causing drag and reducing the efficiency and maneuverability of the fouled ships. • Bryozoans may also foul pilings, piers, and docks. • Certain freshwater species occasionally form great jellylike colonies so huge they clog public or industrial water intakes. • Bryozoans produce a remarkable variety of chemical compounds, some of which may find uses in medicine. – One compound produced by a common marine bryozoan, the drug bryostatin 1, is currently under serious testing as an anti-cancer drug. MORPHOLOGY Classification & Range • Phylum Bryozoa – Class Stenolaemata (Ordovician-Recent) • Order Trepostomata (Ordovician-Triassic) • Order Fenestrata (Ordovician-Permian) • Order Cyclostomata (Ordovician-Recent) – Class Gymnolaemata (Ordovician-Recent) • Order Cheilostomata (Jurassic-Recent) General Morphology and Ecology • As bryozoan individuals are quite small, they are commonly observed under the microscope from longitudinal or transverse thin-sections. • Bryozoans come in a variety of colonial growth habits that can easily be observed without thinsections. • Like corals, the growth habit of bryozoans can be classified as encrusting, massive or domal, or erect. • Generally speaking, byozoan growth-habits are a function of water energy similar to corals which lived in level-bottom communities; – encrusting and massive forms are found in highenergy environments – delicate branching and erect forms lived in quite environments. Encrusting Massive or Domal Erect CLASSIFICATION • Division of bryozoan groups is based on surficial morphology, extra-zooidal structures, colonial growth habits, zooid morphology, presence of specialized zooids (e.g., maternal zooids), and internal structures of the zooecium. • Colonial bryozoans come in two basic types: – 1. Those with tightly packed zooecia which share zooecium walls, they have multiple pores and a well defined mature and immature region such as in the trepostomes, cyclostomes, and the fenestrates. – 2. Those with moderately to loosely packed zooecia usually encrusting one-zooecium-thick, and commonly with frontal walls as typified by the Cheilostomes Class Stenolaemata • Ordovician-Recent • The stenolaemate bryozoans quickly radiated in the early Paleozoic and are very characteristic fossils of Paleozoic rocks, sometimes making substantial contributions to the formation of reefs, calcareous shales, and limestones. • They included forms with robust skeletons • There were also forms with delicate, branching fanlike skeletons such as the fenestrates. • With the exception of one order of stenolaemates, the Tubuliporata or Cyclostomata, all of these Paleozoic bryozoan lineages were severely impacted in the Permian extinction: cryptostomates disappeared at the end of the Permian (245 million years ago), while a few other lineages lingered until the end of the Triassic, about 210 million years ago. • Tubuliporate bryozoans have survived to this day, and in fact underwent a remarkable radiation in the Cretaceous, but are no longer dominant today. Order TREPOSTOMATA • Trepostomes are characterized by long-curved zooecia separated by thin walls. • Each zooecium has mature and immature regions. • Apertures of autopores are typically polygonal. • Trepostomes can be differentiated from similarlooking cryptostomes by the thinner walls between their zooecia. • The specimens are erect forms, whereas these specimens are massive. TREPOSTOMATA Order CYCLOSTOMATA • Cyclostomes are characterized by zooecia that are simple tubes which lack partitions (diaphragms) and have rounded apertures and well defined mature and immature regions. • Most cyclostomes are encrusting forms and some, can be quite small and very loosely arranged creeping zooecia. CYCLOSTOMATA Order FENESTRATA • Fenestrates are characterized by their zooaria morphology which form a mesh or net-like shape with zooecia-bearing rods and open window-like regions called fenstrules. • Most fenestrates have considerable extra-zooid skeleton material which is necessary for support. • This order is typified by erect, delicate morphology. • Some fenestrates have considerable extrazooidal material such Archimedes which is an axial rod that supports the net-like zooecia. FENESTRATA Class Gymnolaemata • Ordovician-Recent • Uncalcified gymnolaemates are known as fossils almost exclusively as distinctive borings in carbonate substrates such as shells. • Non-boring, non-calcified gymnolaemate bryozoans are extremely rare as fossils and known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous only. • Calcareous gymnolaemates did not appear in the oceans until the Cretaceous, during which time they diversified rapidly from a very few species in the early Cretaceous. • By the end of the Cretaceous, there were over 100 genera of gymnolaemates. • They continued to diversify in the Cenozoic: today there are over 1000 genera, comprising the bulk of bryozoan diversity in today's seas. Order CHEILOSTOMATA • Cheilostomes are characterized by their loosely packed colonies of box or coffinshaped zooecium. • Many have round apertures and large frontal areas on which brood pouches which house the maternal zooids can often be observed. CHEILOSTOMATA The Brachiopoda Brachiopods • The brachiopods are a large group of solitary and exclusively marine organisms with a very good geologic history throughout most of the Phanerozoic and are among the most successful benthic macroinvertebrates of the Paleozoic. • They are typified by two mineralized valves which enclose most of the animal. • Brachiopods are filter feeders, which collect food particles on a ciliated organ called the lophophore. • Brachiopods differ in many ways from bryozoans (in both soft and hard-part morphology), and are thus considered by most workers as a separate but closely related phylum. • However, one of the most distinguishing features of brachiopods is the presence of a pedicle, a fleshy stalklike structure that aids the animal in burrowing and maintaining stability. Pedicle Lophophore Morphology BRACHIOPODA- Classification Phylum Brachiopoda (Cambrian-Recent) Class Inarticulata (Cambrian-Recent) Class Articulata (Cambrian-Recent) Order Orthida (Cambrian-Permian) Order Strophomenida (Ordovician-Jurassic) Order Pentamerida (Cambrian-Devonian) Order Rhynchonellida (Ordovician-Recent) Order Spiriferida (Ordovician-Jurassic) Order Terebratulida (Devonian-Recent Class Inarticulata • Inarticulate brachiopods do not posses teeth and sockets, nor do they have clearly defined diductor muscles. • Instead, the valves are held together by a complex of adductor muscles. • Although some inarticulates construct their valves of calcite, most have shells of a mineral composition of chitin and calcium phosphate which can be recognized by its shiny, enamel-like luster. • Inarticulate brachiopods usually lack surficial ornamentation except growth lines. • The classic example of the inarticulates belong to the order Lingulida. • The linguloids are small, biconvex, with usually oval or circular outlines. • This order has quite a long geologic history with some genera (and possible species) remaining relatively unchanged since the Cambrian Class Inarticulata • The only brachiopods to support a minor commercial fishery, lingulate brachiopods are also among the oldest of all brachiopods, and the most morphologically conservative, having lasted since the Cambrian with very little change in shape. • The preserved specimen of a living lingulate, Lingula, shows the typical tongue-shaped shell (hence the name Lingulata, from the Latin word for "tongue") with a long stalk, or pedicle, with which the animal burrows into sandy or muddy sediments. Unlike the shells of almost all other marine organisms, which are typically made of calcium carbonate, the shells of lingulids are composed of calcium phosphate. The rest of the body is fairly typical of brachiopods in general, but the pedicle is quite long. This facilitates burrowing; extant Lingula is typically found burrowed in soft muddy sediments with only the valve edges protruding. Class Articulata • Articulate brachiopods differ from inarticulates in that the articulates posses teeth and sockets and mineralized lophophore supports. • The classification of articulate orders and suborders depends primarily upon characters of the hinge and beak areas (including hinge length, teeth and sockets, pedicle opening, etc....) and perhaps more importantly, although more difficult to asses, the nature of the lophophore support. • Other features (such as the shell microstructure, surface ornamentation) sometimes are quite diagnostic of several orders and suborders of brachiopods. Order Orthida • Shells of orthids are typically strophic (having an elongated hinge line) • The shape is generally semi- or subcircular in outline. • Valve convexity is usually unequally biconvex with a slightly inflated pedicle valve. • Orthids are typically covered with fine diverging radial costae. Orthida Platystrophia Late Ordovician Strophomenida • The Strophomenida were the largest order of brachiopods, with about 400 genera. • They were also by far the most morphologically diverse group, and included some very unusual forms, as well as more "normal" forms. • Strophomenids first appeared in the Ordovician and persisted until the middle Jurassic. Strophomenida • Strophomenids may be identified by their supra-apically located pedicle foramen, at least in young shells. • Adult strophomenids lacked an open pedicle foramen, and usually lived attached to the bottom or to other objects by the pedicle valve. • One group of strophomenids, theproductids, were characterized by very long spines extending from the shell. • These are thought to have functioned as a sort of "snowshoe," supporting and stabilizing the organism on soft muds. • Other strophomenids were attached to the bottom by a coneshaped pedicle valve, with the upper valve covering the cone like a pot lid. • The unusual brachiopod Prorichthofenia from the Permian of Texas is one of these unusual conical forms. • This shape is convergent on that of other attached organisms, such as Paleozoic rugose corals and living scleractinian corals, and it is though that, like corals, some strophomenids bore photosynthetic algae inside their tissues that helped to supply them with food. Prorichthofenia Rugose Coral Order Pentamerida • Shells of pentamerids are generally biconvex. • Pentamerids are typically ovoid, circular, triangular, or more commonly pentameral in outline. • The interior of the shell is typified by a prominent medial ridge or septa in the brachial and/or pedicle valve. • Also diagnostic of pentamerids is a spoon shaped structure modified from plates in the pedicle valve called the spondylium which supported muscle tissues Pentamerida Pentamerids grew to sizes of over 10 cm, and they represent one of the largest types of dwellers within Silurian reefs. A thickened beak area served as a weight to stabilize the shell in the sediment, and there was no fixed attachment. Pentamerid brachiopods often lived as clumps of individuals. Rhynchonellida • Rhynchonellids look a bit like little nuts. • Their hinges come to a point, a condition paleontologists call non-strophic. • They are often ridged. • The commisure, the line between the two valves or shells, is zig-zagged, as can be seen in the somewhat unusual asymmetric rhynchonellid Rhactorhynchia. • The earliest fossil rhynchonellids are from the Ordovician period. • During the Mesozoic Era, rhynchonellids were the most abundant brachiopods. • A few species still exist today. Rhynchonellida Rhactorhynchia Spiriferida • Spiriferids are easy to identify. • They often have an extended hinge line so wide they look winged. • Other prominent characters are the fold and the sulcus that you can see. • The feature that gives the spiriferids their name ("spiral-bearers") is the internal support for the lophophore; this support, which is often preserved in fossils, is a thin strip of calcareous material that is typically coiled tightly within the shell. • Fossil spiriferids first appear in the Ordovician period. • They were extremely diverse during the Devonian period and later went extinct during the Jurassic period. • Some fossil brachiopods make spectacular finds, replaced by pyrite Terebratulida • Most living brachiopod, are representative of the group; terebratulids. • Terebratulids first appear as fossils in the Devonian. • Terebratulids are responsible for the name of "lamp shells" for brachiopods; their shells resemble ancient oil lamps, with the pedicle foramen resembling a wick. Terebratulida Paleoecology • All brachiopods are filter feeding, sessile (nonmobile) bottom dwellers. • They are exclusively marine, but inhabit a variety of bottom environments at various depths and latitudes. • Brachiopods are either free-living or rooted by their pedicle to the substrate. • During life, they can be oriented either vertically, inclined, or horizontally to the substrate. • Typically brachiopods oriented vertically during life will have equally biconvex shells, whereas inclined and horizontally oriented ones will be unequal inflation being plano-convex, concavoconvex Infaunal • Living totally buried within the sediment. Brachiopods living this way are oriented posterior downward, and are usually stabilized by their downward projecting pedicle. • Lingulid inarticulates are among the only brachiopods to exploit this infaunal environment The pedicle is quite long. This facilitates burrowing; extant Lingula is typically found burrowed in soft muddy sediments with only the valve edges protruding. Semi-Infaunal • In this position, the animal is oriented vertically (posterior downward) and is only partially buried in the sediment; they may or may not be attached by their pedicle. Reclining • In this position, the animal is in effect floating horizontally on (or partially within) the sediment with the pedicle valve as the lower valve. • Generally, reclining brachiopods have a concavo-convex or plano-convex shape. • Other modifications include large surface area and spines to help the critter float. • The pedicle opening is usually not present. • Note that one of the specimens also bears attachment points for spines, which served as an additional adaptation for reclining in soft sediments. Epifaunal • In this position, the brachiopod is attached either to the sediment or other object (e.g., marine plants) by their pedicle.