Tragedy 2

advertisement

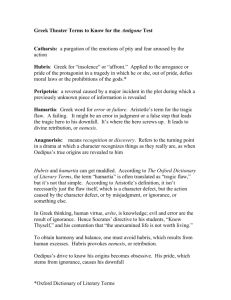

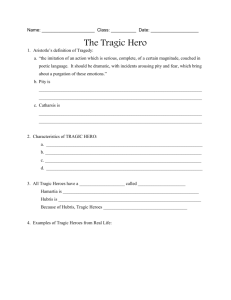

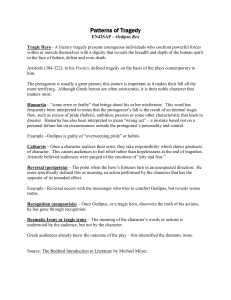

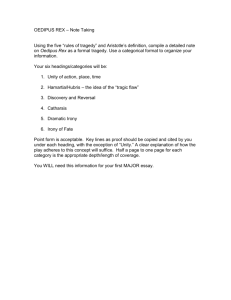

What is Tragedy? An “imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and has sufficient size, in a language that is made sweet…exciting pity and fear, bringing about a catharsis of such emotions,” is now Aristotle defined tragedy Hubris Hubris or hybris (Greek ὕβρις), according to its modern usage, is exaggerated self pride or selfconfidence, often resulting in fatal retribution. In Ancient Greek hubris referred to actions taken in order to shame the victim, thereby making oneself seem superior. Hubris was a crime in classical Athens. Violations of the law against hubris ranged from what might today be termed assault and battery, to sexual assault, to the theft of public or sacred property. Crucial to this definition are the ancient Greek concepts of honor (timē) and shame. The concept of timē included not only the exaltation of the one receiving honor, but also the shaming of the one overcome by the act of hubris. This concept of honor is akin to a zero-sum game. Hubris Aristotle defined hubris as follows: – to cause shame to the victim – not in order that anything may happen to you, nor because anything has – happened to you, but merely for your own gratification. Hubris is not the – requital of past injuries; this is revenge. As for the pleasure in hubris, its – cause is this: men think that by ill-treating others they make their own – superiority the greater. Hubris Hubris against the gods is often said to be the "tragic flaw" ("error") of characters in Greek tragedy, and the cause of the "nemesis" or destruction, which befalls these characters.[citation needed] However, this represents only a small proportion of occurrences of hubris in Greek literature, and for the most part hubris refers to infractions by mortals against other mortals. Therefore, it is now generally agreed that the Greeks did not generally think of hubris as a religious matter, still less that it was normally punished by the gods.[2] Hamartia Hamartia (Ancient Greek: άμαρτία) is used in Aristotle's Poetics, where it is usually translated as a mistake, flaw, failure, fault, or sin. There is debate as to what exactly hamartia means in Aristotle's Poetics. It has been interpreted as referring to a 'tragic flaw in the character of the protagonist (the tragic hero), but the word, in Homeric Greek, refers to a warrior who has missed his mark. If an archer or a spear thrower misses, άμαρτες has occurred. Those who prefer this interpretation argue that the Greek tragedies contain no clearly identifiable tragic flaws, and have been twisted to fit the supposed 'tragic flaw' theory.[citation needed] Peripeteia Peripeteia (Greek, περιπετεῖα) is a reversal of circumstances, or turning point. The term is primarily used with reference to works of literature. The English form of peripeteia is Peripety. Peripety is a sudden reversal dependent on intellect and logic. Aristotle defines it as "a change by which the action veers round to its opposite, subject always to our rule of probability or necessity." Peripeteia includes changes of character, but also more external changes. A character who becomes rich and famous from poverty and obscurity has undergone peripeteia, even if his character remains the same. Peripeteia When a character learns something he had been previously ignorant of, this could be described as peripeteia; the character has been turned from a state of ignorance to that of knowledge, or from doubt to certainty. However, this is normally distinguished from peripetia as anagnorisis or discovery, a distinction derived from Aristotle's work. Aristotle considered anagnorisis, leading to peripeteia, the mark of a superior tragedy. Anagnorisis Anagnorisis is the recognition by the tragic hero of some truth about his or her identity or actions that accompanies the reversal of the situation in the plot, the peripeteia. Oedipus's realization that he is, in fact, his father's murderer and his mother's lover is an example of anagnorisis.